Rewind: Four Tet

Kieran Hebden, better known as Four Tet, has a considerable, not to mention incredibly consistent, […]

Rewind: Four Tet

Kieran Hebden, better known as Four Tet, has a considerable, not to mention incredibly consistent, […]

Kieran Hebden, better known as Four Tet, has a considerable, not to mention incredibly consistent, back catalog. In addition to producing his own acclaimed records, the London-based producer has worked with late jazz drummer Steve Reid, folk singer-songwriter Vashti Bunyan, Burial, and Thom Yorke of Radiohead, while remixing countless others. Following the 2010 release of There Is Love in You, Hebden released a series of 12-inch singles that he’s now compiled into a new, album-length release called Pink, which he’s releasing through his own Text label. Over the phone from his home in London, Hebden gladly jogged XLR8R through his releases, starting with the nearly 37-minute-long track Thirtysixtwentyfive all the way through his latest singles. The Four Tet aesthetic, while identifiable, has taken a number of daring, radical turns, each quite enthralling. His newest material is some of his best yet, and undoubtedly his most club oriented.

At one point in our conversation, he remarked, “One of the things I’m really happy about with my back catalog is that my musical journey is very, very well documented, from the most naive beginnings of what I did right through. It’s all there in a clear way for people to see.”

Thirtysixtwentyfive (1998, Output)

Even before [my old band] Fridge was happening, and while Fridge was going on, something I had always done was make music in my bedroom at home. I had a four-track tape recorder and would play around with ideas—learning my chops, I guess, as a producer. When I got to college, I got my first computer, and was able to start doing sampling and looping and all those sorts of things. That’s when the Four Tet project basically started. I didn’t think about releases particularly; it was just something I was doing. I played the stuff for Trevor Jackson, who ran the Output label and was putting out Fridge records; he was into it and ended up putting it out. The first-ever Four Tet thing that came out was a track called “Field” that was on this compilation album on Leaf Records, [Invisible Soundtracks Volume III]. I wasn’t thinking in terms of long-term project or side project or anything at all—I was just like, “Oh, yeah, here’s some kind of music.” I was so young at the time, and in retrospect, everything was just done in a pretty mellow and natural sort of way. Thirtysixtwentyfive was one of the first things I did that got quite a lot of radio play, which is weird because of the length of it.

Dialogue (1999, Output)

The response to Thirtysixtwentyfive was good, so I started making a bunch more tracks. I started thinking I should try and get enough of these things together to make an album. I was at university at the time, and busy with Fridge as well, because that was my main thing around then. The whole concept of the [Four Tet] project was that I wanted to make something very influenced by jazz music, but the much more cosmic and ferocious end of jazz. The whole “new jazz” thing was happening at the time, and a lot of the dance records that claimed to be jazz influenced were quite polite, as far as I was concerned. I wanted to do something that was more about the darker ends of jazz, and that’s why the project was called “Four Tet,” like “quartet.” I’ve even got this European jazz record that says “Four Tet” on the front. The idea was to make it to fit in with all these European free-jazz records I was collecting. I was buying all the records on MPS and ECM and all these things, learning about all this music. DJ Shadow had just come out with Endtroducing… I was already interested in hip-hop, but to hear somebody make a record out of sampling 20 records rather than just one or two was really inspiring to me. Around the same time, Bundy K. Brown put this 12-inch out as Directions called Echoes, which kind of was the blueprint for the Four Tet thing. I heard that record and was just like, “This is genius—this is taking the whole concept of what people like DJ Shadow are doing and making a modern-day take on spiritual jazz out of it.” There was a lot happening around that time that definitely was inspiring me in a big way.

Pause (2001, Domino)

Dialogue got this quite positive response, people seemed into it, and then Four Tet was as big as the Fridge thing. When I decided I was going to make another record, I had a big criticism of the first one at the time—maybe I still do, in some ways—which was that it was essentially a product of its influences. I felt like I had got a handful of records I was really into and squashed them together, and that’s all it was, whereas the music that I respected most was creating its own sound. People like Timbaland were putting out these incredibly futuristic records, and I felt like, “I’ve got to do something that counts.” When I started to work on Pause, I wanted to have a much broader sonic palette and do something much different. The R&B thing was a massive influence—Timbaland was putting out records with flutes and tablas on them that were worldwide smash hits. That’s when I started looking for much weirder instrumentation to use, and started buying loads of folk records and stuff. After buying loads of folk records to sample, I started to discover that there’d be really nice sounds on there, but not the heaviness or depth I was hearing in jazz records I really liked. Those were things I wanted to bring together: the sounds of harps you might hear on a folk record with the kind of drums you might hear on a Pete Rock record, bringing all those influences together.

Rounds (2003, Domino)

I remember finishing the record and telling the record company, “Well, it’s not a huge development from the previous one, hopefully people will be into it.” I didn’t anticipate the sort of reaction it got. It was definitely the turning point—people seemed to get into that one in a totally different way, which I understand more now when I listen back. I think the concept on Rounds was to take this idea of trying to develop my own sound even further. When I did Dialogue, I was just younger, and didn’t even know why I was making the music. It would get to the process of titling the songs, and I would just give everything any old random name. By the time I did Pause, I was thinking about everything loads more. I was very wrapped up in this idea that making electronic music had become part of my day-to-day life, the same as brushing my teeth, watching TV, seeing friends—making music had become part of that completely. I started to be very conscious of very personal things hidden in the record. Pause had come out, and people had really identified with the song titles and things like that. I noticed people were looking for meaning in my music for the first time, and that made me think about the meaning of it all and what I was trying to achieve. When I listen to Rounds now, it’s like reading an old diary for me—this very specific time in my life, very specific people I was hanging out with, relationships, places I was traveling to, all wrapped up in a record. There are sounds on there of everything from family members to friends, and all the titles were completely relevant to things that were going on with me.

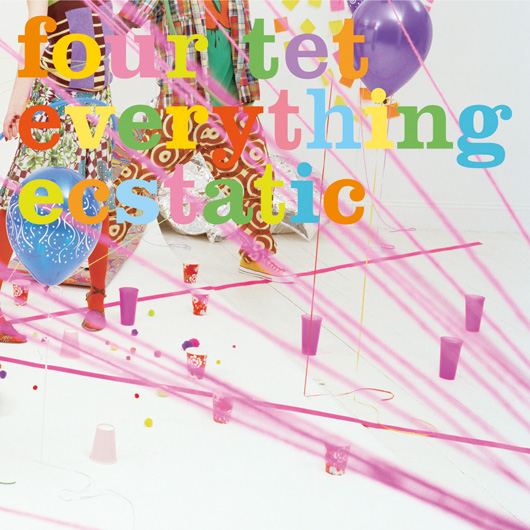

Everything Ecstatic (2005, Domino)

Everybody was suddenly going on about how I was very connected to folk music. I felt it was really missing the point—”Well yeah, there is a folk music influence there, but no more than techno or hip-hop or soul. What about all those other things going on?” So I wanted to get these other influences back in there… The other thing that happened was that, after Rounds came out, I started touring very extensively. At that point, live electronic music—there were very few people doing it, and it was considered quite a weird thing to get up there on stage with a laptop. There was Aphex Twin and a handful of other people doing stuff like that, but not loads. I got really interested in the idea of doing real-time electronic music and improvising.

Everything Ecstatic was made with live performance in mind. The beginnings of the tracks had come out of the live shows I was doing around the Rounds period, which were so much more hardcore and noisy and crazy than any of the music on Rounds. The jazz influence was still there, and I was listening to people like Fennesz, and Jim O’Rourke, who was making all these crazy electronic records. I also discovered all that classic electronic music: Stockhausen, Pierre Henry, that more crazy stuff.

Ringer (2008, Domino)

Everything Ecstatic was the biggest tour I had ever done: six weeks in America, a month in the UK, Europe, loads and loads of stuff. I hit this point at the end of that tour, “I’ve had enough.” I did this big show in London—my biggest show yet—and my feeling at the end of it wasn’t, “Let’s try and do a bigger one,” it was more like, “I’ve done this now. I’ve had this experience. What’s next?” I wanted something to push me in a totally new direction—I kind of wanted to feel scared again by music. And that’s when I met Steve Reid and got really, really into that whole project with him… it was a huge musical epiphany. It took my whole interest in live improvisation full force ahead. At that point, I was kind of doubting that I’d ever make another Four Tet record.

The one thing I got back into was DJing—purely because it seemed like dance music was having a quiet kind of moment. It was kind of uncool. I went to play in Ibiza with Timo Maas, and then he invited me to come and do this residency with him at this club in London. It seemed so different from everything else; it just felt refreshing. There was something really unpretentious about it as well. I was just someone supplying music and people were there to dance, it just felt very natural. Then I met James Holden from Border Community, and started listening to a lot more house and techno music than I had in a while. I hit a point where I was DJing all the time and I finally was just like, “I want to make some of my own music to play in these clubs.” That got me making solo electronic music again. I knew the music would be really different at that point, with the combination of the DJing and the stuff I was doing with Steve Reid. An EP felt like the right thing to do because I hadn’t put anything out in 3 or 4 years. [Ringer] opened the doors for me, really, in terms of making this kind of 4/4, dance-oriented music.

There Is Love in You (2010, Domino)

Once I decided to make an album, it became a really massive project. I thought, “If I’m gonna put out another record at this point, when I’ve done so much stuff, it’s got to really, really count.” I spent well over a year on There Is Love in You, working on the tracks—I felt like it had to be totally right. Before Plastic People, I was doing James Holden’s night at this club called The End—that’s where I did Ringer. The End closed down, and I thought, “What am I going to do now?” Then Plastic People, which was a club I loved, said I could do something there. The Plastic People residency lasted like a year and a half, and I made There Is Love in You during that time—I was testing out all those tracks the whole time. The whole experience of the club, the records I was playing, everything that was going on with that club night was basically the whole driving force and concept behind that album. I was making that album, and Dan Snaith was making that last Caribou record, Swim, and we were trying out all the tracks for both records every month at this club. I think for the both of us it was a really defining kind of moment.

Pink (2012, Text)

After There Is Love in You, one of the things I decided was that I didn’t want to go into that whole album process again: hiding away for 18 months making a record, having to do all the press associated with it, and the touring… I decided to just think in terms of singles. For all the 12-inches I’ve been putting out over the last year, I made the tracks and put them out, not thinking about what was gonna happen next. It had all been vinyl only, and it just hit a point where I had quite a few tracks. I was like, okay—there’s a good collection of stuff here, let me group it together into an album.

I’m trying to eliminate the kind of things that don’t feel natural to me anymore, rather than force myself through them… I was doing 12-inches because it was a quick way to get it out, and it’s the right format for it. I’d send it to a lot of DJs before I’d send it to anyone else. I was really making music for other DJs to use as well.

I moved to New York for a year and came back to London a few months ago. It did have a big impact on a lot of these tracks—a lot of these tracks I made in New York. Once I got away from the UK, I got more interested in the music scene here. When I’m in London, I’m wondering what’s going on in Berlin, and when I was in New York, I was listening to Rinse FM all the time. New York gave me to an opportunity do something more of London.