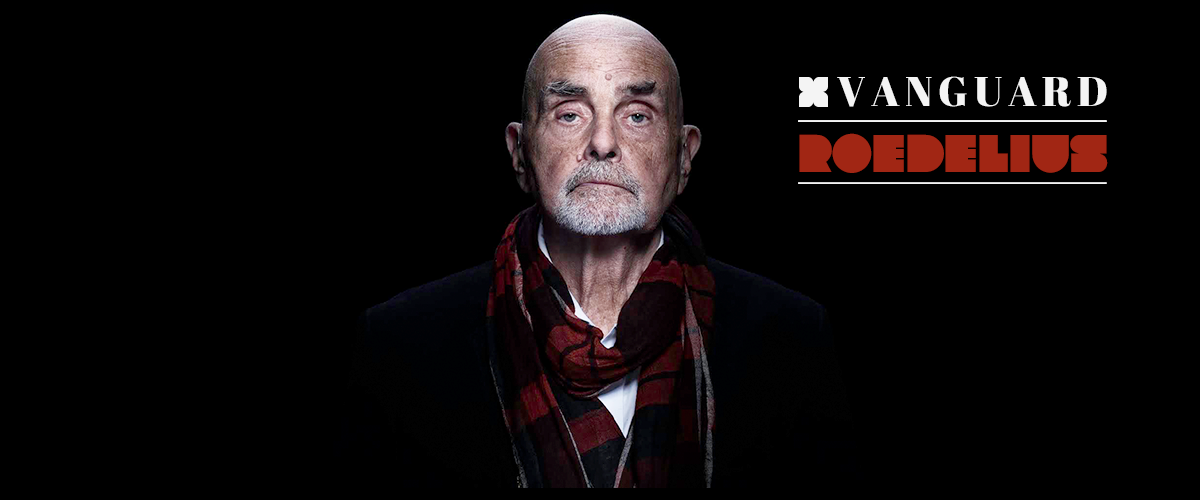

Vanguard: Roedelius

Dynamic as ever at age 80, the musical trailblazer discusses his collaboration with Christoph Muller and the upcoming Harmonia box set.

Vanguard: Roedelius

Dynamic as ever at age 80, the musical trailblazer discusses his collaboration with Christoph Muller and the upcoming Harmonia box set.

The willingness to step into the unknown has been one of the keys to mankind’s progress. Whether it’s the compulsion of humanity’s ancestors to leave the place of their birth to seek fertile lands, or the desire of a theoretical physicist to delve deep intro the intricacies of the universe, the urge to go beyond what is known is essential to the act of discovery. That’s as true of the artistic realm as is of any other, and it’s been a driving force in the career of Berlin’s Hans-Joachim Roedelius. Born in Berlin in 1934, Roedelius was, for a short spell, a child actor; later, in the ’60s, he toiled as a physical therapist. But then, he made the leap into uncharted territory: In the final months of that decade, he, Dieter Moebius and Conrad Schnitzler (of Tangerine Dream, among other claims to fame) formed Kluster, a wildly progressive, experimental outfit—considered one of the early progenitors of what became known as Krautrock—incorporating rudimentary electronics alongside more traditional instrumentation. By 1971, Schnitzler had left; Roedelius and Moebius carried on as Cluster, often collaborating with the likes of studio wizard Conny Plank (and later, Brian Eno) while continually pushing their sometimes jarring, sometimes atmospheric, always fascinating sonic explorations over a series of groundbreaking albums.

“We were learning from point zero,” Roedelius recalls of those years. “We created something that wasn’t around before.” But his forays into aural experimentation were just beginning. In 1971, he and Moebius moved deep into the idyllic Lower Saxony countryside, along the Weser River, where they were joined by fellow Krautrocker Michael Rother of the band NEU!. The three, after a short period of musical trial and error, formed Harmonia, a group that proved to be at least as influential as Cluster. Both precise and romantic, the band’s music had a an idealized, dreamlike feel—one that leaned more heavily on synthetic sounds more than Cluster’s recordings ever did—that was pastoral and intimate, yet full of joy and optimism. Their studio albums, including 1974’s Musik Von Harmoniaand the following year’s Deluxe, are considered touchstones of electronic music to this day; Eno famously praised Harmonia as “the world’s most important rock group.” (Not bad for a band that eschewed 99 percent of rock music’s trappings.)

After recording what was eventually known as the Tracks and Traces album in 1976—which went unreleased until 1997—Harmonia disbanded. Rother is still playing, but sadly, Moebius passed away this past July—Roedelius, however, is seemingly as active as ever. Working both solo and in conjunction with others, his penchant for experimentation still runs strong—and as if to prove the point, his latest release is a collaborative work with Gotan Project’s Christoph H. Müller called Imagori. Released on the Grönland label, it’s an album-length set that’s rich, warm and occasionally dense, with Roedelius’s rippling piano work weaving its way through Müller’s electronic backing. And on October 21, Grönland is putting out the sprawling Harmonia box vinyl set Complete Works, with Musik von Harmonia, Deluxe, Tracks and Traces, Live 1974, and Documents 1975 (previously unreleased recordings from Hamburg gigs along with a pair of studio tracks) accompanied by a 36-page booklet, a poster, pop-up artwork, and a download code for the full set in digital form. In the midst of all this activity, XLR8R caught up with Roedelius via Skype; on the eve of his 81st birthday (October 26, in case you are wondering), he was funny, charming, and seems to have lost none of the joy that a career spent exploring can bring.

What was the genesis of Imagori? How did you first meet up with Christoph Müller?

I was working in Paris with some designers on a project called Grateful Vanity. They created two sound sculptures, and they wanted to present it in a special way at this big art center near Paris, so they invited Christoph to come and join me for an improvisational set. We liked what we did so much that we decided to do something else together afterwards.

Müller isn’t exactly a kid—but he does come from a different generation of artist. And you’ve certainly collaborated a lot in the past; much of your career consists of these ever-morphing partnerships. Do you enjoy working in collaboration, and specifically working with younger people?

It’s always been collaboration; Cluster was certainly a collaboration, for instance, and much of what I’ve done since then has been as well. And much of it has been with younger people. Not many people are as old as I am! [laughs] So I guess it’s a bit out of necessity. But I do enjoy working with younger artists.

Your music, especially your work with Cluster and Harmonia, undoubtedly had a lot of influence on many of those younger artists.

Yes, and I think that’s because what we were doing was so authentic. We were learning from point zero; we created something that wasn’t around before; it was musical actualism, in a way. We were doing things step by step, and had to learn how to do it in a relevant way—relevant to people’s ears. It took a long time to do do it; after Cluster began, I think we needed about three years before we became aware that what we did was becoming something that people really liked.

“We always liked what we were doing—we had our concept, we were developing our own tone language, and we were happy with that from the start.”

That must have been quite a fulfilling realization.

It was, even more so because we came from such different professions, none of which were music. Moebius was from graphic design, Schnitzler was someone who worked with metal, and I was a physical therapist. It was a strange base for what we ended up doing afterwards. But we always liked what we were doing—we had our concept, we were developing our own tone language, and we were happy with that from the start. That was a challenging and interesting time—creating something out of a moment, however we were able to do. And I think people could get the feeling that we were having fun doing it.

You really do get a sense of playfulness when you listen to the music. Do you think that because you were starting from a naïve musical viewpoint, that allowed you to develop your music—to create that tone language—in the way that you did?

Yes, and that’s the big difference—because we did it from our own impetus and not someone else’s, we were able to do what we did. We had no plan about what would come out. After time, we became more and more aware of what we were doing, and really liked what we were doing—and at some point, people all over the globe liked it.

You sound a bit surprised at that.

I am. I still am. [laughs]

Going back to Imagori, how did the album’s songs take form?

I had some stuff which was not yet elaborated, and I really though that there should be somebody who could work with it as a base for their own ideas. Christoph was the right person for it; he really like the stuff, and he really was excited to be working with it. He had some time between working with Gotan Project and working with Plaza Francia, and he really got into it. And I think you can see how much he liked it in the result! I like it very much; it’s very different from music that I am usually involved with. And I think it’s different than his music as well.

It’s nice to see your old friend Brian Eno on this album’s “About Tape.”

Yes, it is! It was Christoph’s idea hat we use the words from an interview Eno had done. I was in London, and I met up with Brian and told him, “We did a piece with your text on it!” “Oh, you did?” [laughs] He didn’t even listen to it; he just agreed in the first moment that it was okay.

What did those original sketches that you gave to Müller consist of?

What I gave to him were just these very old things done on very old equipment. There was a lot of things done on piano, and a lot of it was on old synthesizers. It was actually quite diverse.

Do you have plans to continue to work with Müller?

We do. We have already played live together a few times, trying to recreate some of this material but in a different way—to revitalize it. We were remixing our own remixes, in a way.

I’m guessing that you get a kick out of remix culture.

It’s a great culture—I love it. So many good and astonishing projects have come out of it.

“It was a very vibrant time—everything was new, everything was interesting, and everyone around us was deeply into what was going on.”

Besides Imagori, you also have Harmonia’s box set, Complete Works, coming out soon. Going back to Eno for a minute, he was quoted as saying that Harmonia was the “world’s most important rock group.” That’s quite a declaration.

Yes. [laughs] David [Bowie] and Brian really like what we were doing. It was around the same time that they were doing Low and Heroes, and we each were influenced by the other. It was a very vibrant time—everything was new, everything was interesting, and everyone around us was deeply into what was going on. Harmonia’s work was quite deep in a way, I think.

And it was hugely influential; you can draw a pretty direct line between what was going on in Berlin and its surroundings back then, and so much great music that came after. Were you guys aware that you were doing important work at the time?

Not really. We just did it. We made [Cluster’s] Zuckerzeit and Sowiesoso at around the same time. We were in a special situation, in the middle of Germany beside the river, and we had to work a lot. We had to go to the forest to cut the wood; we had to grow our own garden. We were really going back to our roots, away from noise and the psychology of the city, and that’s part of what dictated the way that we worked. It was like living in paradise, and that shows up in the music.

It is quite a utopian sound, and that might be why it holds up so well.

I think so. And I hope that this release will get a lot of people to hear it again, or maybe for the first time. And I think Grönland did a great job with this. It’s such a gift for us—and I think it’s a gift for the world, as well. I hope that this brings us a new type of audience…a new generation. I know that a lot of young musicians really like the music, and refer to us as influences.

You worked with Conny Plank on the Deluxe album, and he was also a big part of Cluster’s sound. What was he like?

He was a great guy, and a good, good friend of ours. He was so much more than a sound engineer; he had huge artistic abilities, and had so much input into everything. He wasn’t just a sound engineer—he was a great musician as well. He was on so many important productions, more than I ever was. For a long period of our lives when we were very poor artists, he gave us homes, he fed us…he was hugely important.

He’s one of those guys who was sort of in the center of everything, to the point where modern music may have developed far differently if he hadn’t been around.

Yeah, that is for sure. He was the nucleus of so much.

“There is no split between my music and my private live. Work, family, life…it’s all one.”

The name Harmonia fits your music so well. Was it meant to describe the sort or music that you were making?

Well, it was really about the situation in which we were living, in this beautiful place, which was somehow harmonious. Michael Rother is still living there.

Really?

Dieter Moebius also was still there, but now he’s not with us anymore. But Michael is still there. You should go there someday!

You left there quite a while ago, and are now living in Austria, right?

I’ve been in Austria since 1978. My wife is Austrian, but the real reason that I left that beautiful utopia is that the nuclear plant upriver broke—and nobody told anybody. Some kids died. Our first child, our daughter, had just come to birth, and when we did find out about what happened, we immediately moved away. And since my wife is Austrian, we moved to Austria—which was really a good step. Getting somewhere new was good, but being in Austria really helped me a lot in so many ways. I got pensions from the state, from institutions, from private people…I wouldn’t have been what most of what I’ve done since ’78 if I had not been in Austria.

Well, thank you, Austria!

Yes, thank you very much, Austria! The kind of support that they give to artists is very important to the Austrian spiritual culture.

When your Sinfonia Contempora No. 1 came out in 1999, you stated “”Since the beginning of my career nothing was more important to me than to find my own musical language. I have, so I believe, eventually found it.” Do you still feel that way, or is it an ongoing process?

I found it. I know that what I am doing is me. There is no split between my music and my private live. Work, family, life…it’s all one. I wouldn’t have been able to keep doing what I do if I hadn’t have discovered what it is that I am doing. And I think that the ancestors took the first steps to what I am doing now: Cantors, preachers, teachers and the others have all prepared the way that I am going.

Imagoriis out now;Complete Workscomes out October 21. Roedelius will be celebrating his upcoming birthday at the Semibreve festival on October 30 with an exclusive performance with guests André Gonçalves, José Alberto Gomes, Rui Dias and visual artist Maria Mónica.