In the Studio: Shades

Sander Dennis (a.k.a Eprom) and Alix Perez detail the processes behind their pulsating beats.

In the Studio: Shades

Sander Dennis (a.k.a Eprom) and Alix Perez detail the processes behind their pulsating beats.

From their respective studios in Portland, United States and London, United Kingdom, Sander Dennis (a.k.a Eprom) and Alix Perez make bone-crushing experimental bass music as Shades. First connecting in Los Angeles while in town to make beats for Foreign Beggars, it became apparent that they had much more in common than this commission: a mutual appreciation for vintage horror and sci-fi, in particular directors Stanley Kubrick, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Ridley Scott, as well as visual artists working in a neoclassical space. This gave them a basis to continue their conversations, and, less than a year later, Shades was born with a self-titled outing on Alpha Pup, morphing the remnants of these Foreign Beggars sketches into pulsating beats music and future hip-hop.

In the period since then, Shades has developed into one of the most exciting collaborations in contemporary bass music. Despite extremely busy solo careers—Eprom operates is more traditional beats, and Perez has long been a liquid drum & bass heavyweight—the duo have maintained a flow of new music, including In Praise Of Darkness, a debut album on Toronto’s Deadbeats Music. The project can be seen as a fusion of both parts, both entities, but it also pushes the envelope forward, creating rich and complex tapestries that transport you to another dimension. During a period of studio downtime, the duo invited XLR8R to learn more about how they make them.

What distinguishes Shades from your respective solo projects?

Alix Perez (AP): The approach to making Shades music is different. It’s very free in terms of the creative process. A lot of sound design and recording happens before any kind of beat or structure happens. Sometimes we record to a BPM but often we don’t. We just push our machines to the edge and aim for the weirdest results and I feel that gives a lot of freedom and results in unusual grooves and rhythms. I’d say we have a particular way of processing too; we use a lot of the same plug ins for the mix down process, with some experimentation from time to time. It feels like things naturally fall into place when writing.

Sander Dennis (SD): There’s a sense in which Shades is both of us finding common ground and there’s another sense it which Shades liberates us to explore hitherto unexplored terrain. We approach Shades dancefloor tracks from the standpoint of working towards a shared aesthetic, which keeps the sound focused. For instance, Alix probably wouldn’t send me the shell of a drum & bass track, and I wouldn’t start going into a crazy rave/acid workout, à la Eprom, and expect it to work for Shades.

Was this always the vision for Shades?

Yes, our vision for Shades is an outlet for both of us to express ideas we couldn’t do with our respective solo projects, so in that sense it allows us to experiment. In another sense though, there is a unified aesthetic behind the project, where we are drawing on the reconnaissance of the neoclassical and gothic themes that we’ve established for the visual dimension of the project. That research informs the music; although we’re not using classical instrumentation, we are developing that visual language through the music. We’ll look at visual references and allow that to inform the mood of music pieces. For example, we are both into the work of Gustave Doré, and may refer to a specific image from Roman, Catholic, or Greek mythology and build music around that theme. The name “Shades” draws from “Dante via Doré,” as well as “Chiron,” “Geryon,” “The Serpent,” and other works that reference antiquity.

What were the first studio experiments like together in 2015?

We just set up a laptop and an M-Audio trigger finger and just loaded up some random samples and tried to make some beats for Foreign Beggars. They didn’t end up using all of the beats so those formed the heart of a new project. Most of those beats were too mental to rap on anyway, so they became the basis of the self-titled EP. We both already had an idea of what we wanted to experiment with, sound-wise, so it all happened quickly. When we were ready to clean up the tunes for release, we spent a few hours in the studio belonging to 12th Planet, where we did the mix downs and tidied up the structure.

What was it about these early sessions that inspired you to make the project permanent?

I think we just got along really well and that made it easy to collaborate. Collaboration is a personal relationship and that’s the most important part. You can be on the same page with your techniques and have complementary vision for the project, but the most important thing is just to get along as people and everything else will happen naturally.

How does it work as a collaboration: are you always working together?

No, we try to work together as much as possible, and lay down the basis of a track, but lately we have started a few projects individually due to location and time. I think that’s valuable as well because it gives each of us an outlet for tracks that don’t fit into our solo projects. But you have to be disciplined to pull that off, especially working from two different sides of the globe.

How do you distinguish between a sketch being used for a solo track or a Shades track?

AP: For me, it’s a lot more open in terms of BPM. A lot of the time I’m working at 170 or 140, especially recently, so Shades gives me a lot more freedom to experiment in tempo.

SD: Yeah, I agree with that, although personally I work at lots of different tempos. Shades has some concrete influences like grime, New York rap, and drum & bass that operate at specific tempos, so for us it’s about how can we take those influences and stray from the native BPM and see what happens. Like, what happens if we do a grime bassline at 90 BPM or a drum & bass breakbeat at 120 BPM, way off their original tempos of origin?

When you aren’t together, how do you send files between one another?

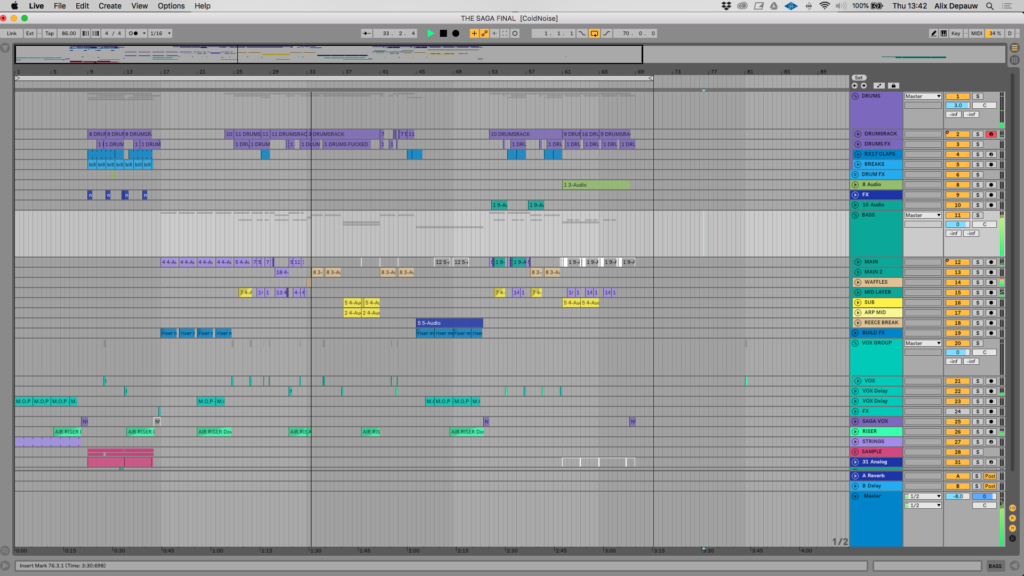

AP: We sync everything via Dropbox. This way, all our projects and files update immediately. We save different versions often so that we can navigate to earlier times if necessary.

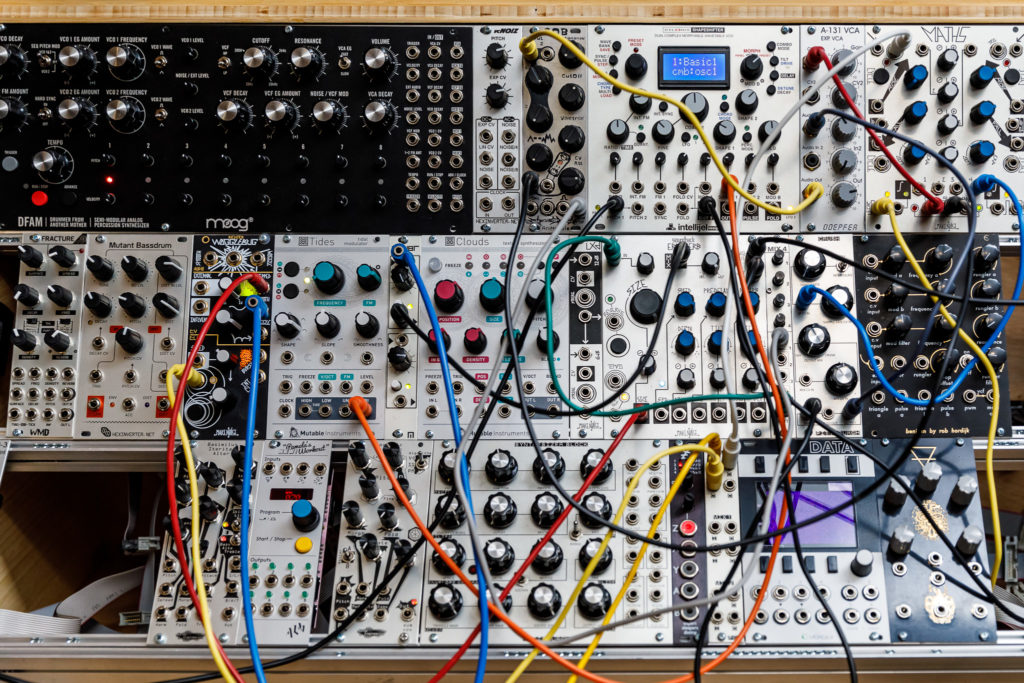

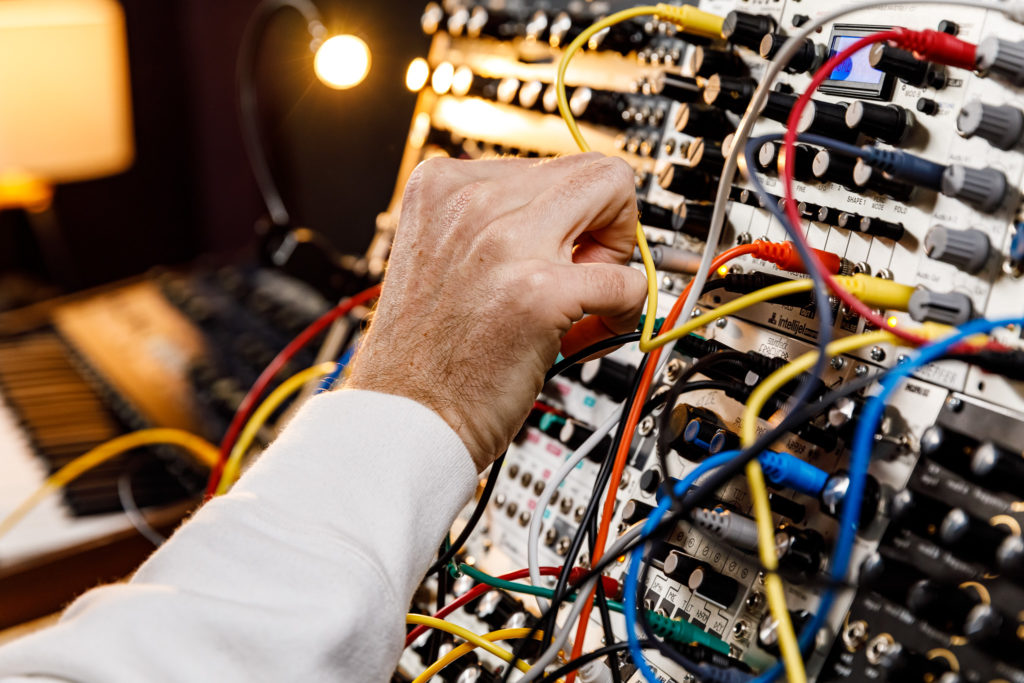

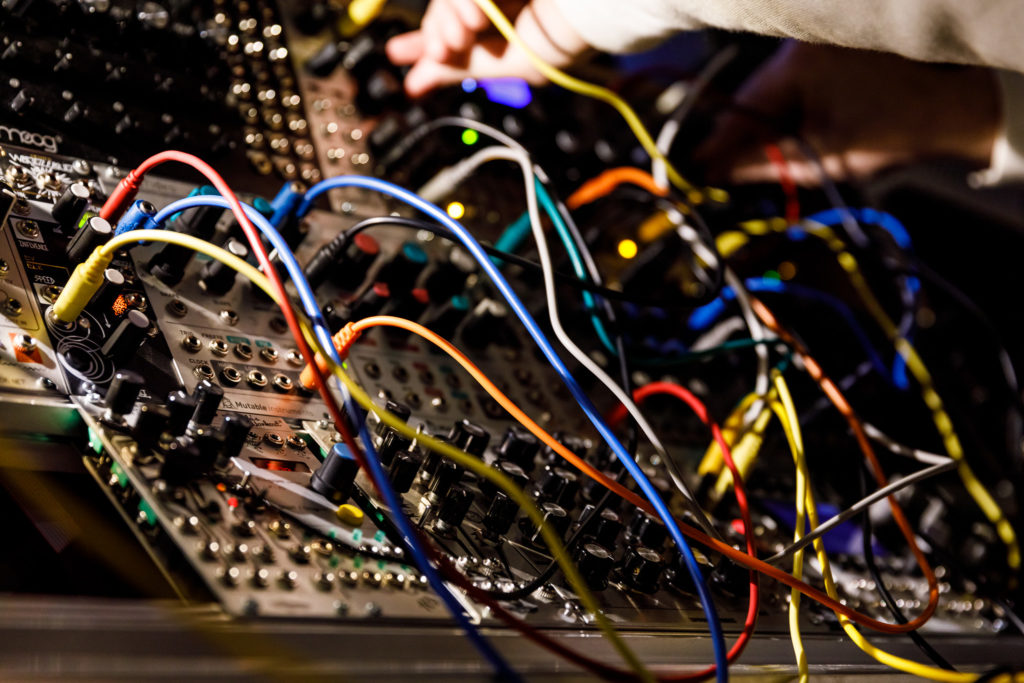

SD: We also have an archive of samples that we maintain when we’re together and not working on tunes specifically but more on sound design. For example, at my studio, in Portland, we’ll record lots of experimental Eurorack modular stuff, or sample my MS-20 mini through a practice guitar amp, and record stuff like that and add it to our shared archive. At Alix’ studio, we have a bunch of other outboard gear, so when we’re together we’ll use whatever’s available to generate new sounds and get some fresh ideas going.

Eprom’s studio. Click to enter gallery.

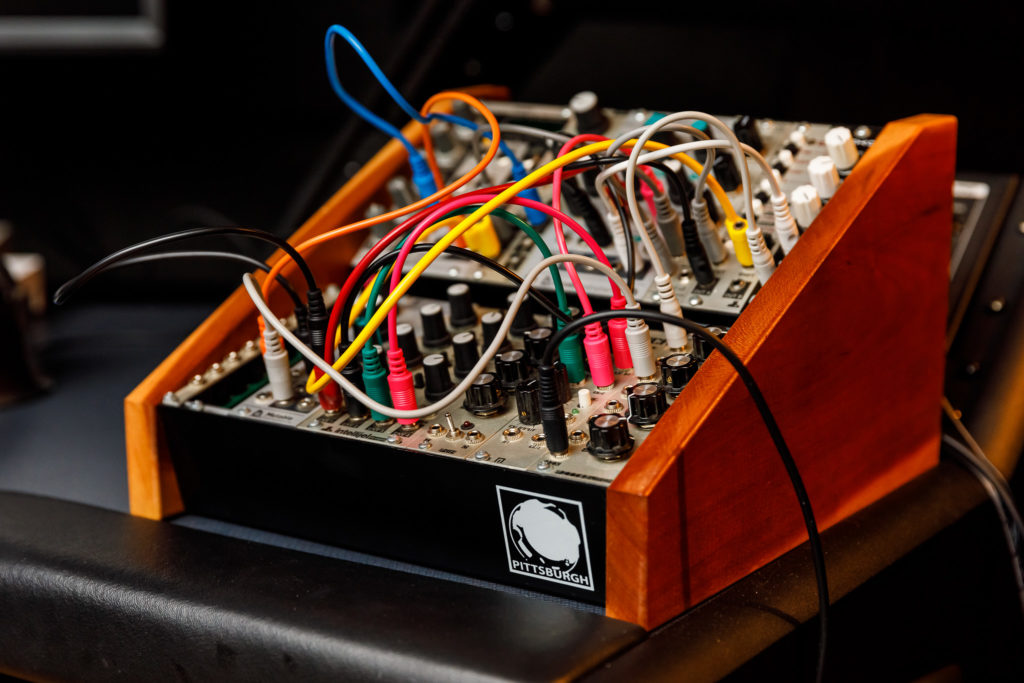

It sounds like your respective studios are different. How do they compare?

AP: We share some similarities in studio setup, but Sander is a lot more modular synth-based. I have a lot more pedals, separate effects units, and hardware synths. My studio is in a purpose-built complex in the north of London. I’m running on Barefoot MicroMain 45 Monitors (we have the same monitors which is handy when collaborating!), Universal Audio Apollo Duo sound card, various hardware synths, pedals. I usually finalise mixes on Audeze LCD3’s. I’m using Ableton Live.

SD: Yes. My studio is a separate building in my backyard. It’s built around a Hackintosh PC, Ableton Live, and several external synths, most prominently a pretty decent Eurorack system that we use to generate ideas and sound elements. I use a Focusrite interface and Barefoot MicroMain 45 monitors, too. The most important thing in a studio is having fun stuff to play with. For my home studio, I want it to sound clean and transparent, but that’s not important when you’re starting a track. The fun factor is more important.

AP: But regardless of setup, sonically everything naturally ends up sounding like Shades. We’re often inspired by new gear and so our methods change from track to track because we’re in a learning period with a new setup. A lot of the time a tune will actually be based around exploring a new technique.

Can you give an example of how a new technique led to a track?

SD: Sure, let’s take “Algor Mortis.” This was based on a process where we set up the modular synth to play a drone, one long sustained note, originating from the Noise Engineering Loquelic Iteritas. We modulated the various parameters of the oscillator with LFOs and other sources of CV randomness. We then loaded the resulting drone into a Sampler instrument in Ableton Live and modulated the start point of the sample with a sample and hold LFO to vary the timbre of the bass sound. We turned this random modulation on and off while recording various takes of the main melody, and picked our favorites to develop into the track.

How do you communicate track amendments?

AP: We usually get on a call every now and then when there’s a lot to be done. During the album process, we spoke and split the work into two. If one of us struggles with a certain track then we will pass it on and takeover and so on.

SD: Yeah, we basically know what direction to go with tunes once they’re at a certain point. If I get lost or feel directionless, I’ll just pass it to Alix and let him take a crack at it. We both trust each other to make improvements, and if we don’t think a tune is going in the right direction we’ll just revert it or create some kind of fusion of the old and new ideas. I think trust is an important part of any collaboration; you have to trust your partner’s creative judgment and they have to trust that any suggestions or changes you make come from a genuine desire to improve the tune.

“We don’t chase tracks that aren’t working down the rabbit hole. We don’t waste a lot of time. We move on and then if someone wants to do a ton of detail work on a song, they’ll do that in a solo session.”

—Alix Perez

How do your respective studio processes compare?

SD: Alix is definitely a stronger mix engineer, I think he gets that coming from a drum & bass background where the music is technically demanding. I’d say I’m more experimental in my methodology; I come from more of a pure sound design background. I also think Alix is better at rolling tunes out. That is, developing a loop or a short passage into a full idea with some structure. I think I’m pretty good at creating atmospheric chord progressions, for example, I’ll spend 20 minutes laying out something in the Max4Live patch Granulator II, creating a background vibe for the tune. Obviously both of us are good with bass lines.

AP: Sander is a great mix engineer. Purely talking about his solo stuff, for example, there’s no denying he is very talented in that department. What really stands out for me though are his methods and unusual ways of “sound designing.” He has lots of interesting ways of treating and generating sounds that are way less conventional than some of my approaches perhaps. This results in really interesting sound production.

As he mentioned, coming from a drum & bass background, I’ve inevitably gained a lot of mixing experience. Due to the high tempo and technicality, everything has to be very precise due to the limitation of room. This has definitely given me the ability to approach difficult mixes at various points!

With this in mind, do you both have separate roles when it comes to Shades, or are you both equally involved at each stage in track-making process?

SD: Not really. Alix and I are both super fast at making tunes, so a lot of the time we’ll actually be working on different parts of the same song at the same time. Even when we’re together, I’ll be on the main computer and Alix will be working in headphones or something, and we’ll sort of work on “A” and “B” sections of the same tune and then stitch it together and finesse the transitions between elements. We both have similar goals so this more often than not ends up sounding pretty good. Typically for our first releases we shared the work on tracks mainly equally, but as we’ve developed we’ve allowed ourselves to pursue individual visions by creating nearly entire tracks on our own and then passing to the other one of us to put the finishing touches on it.

AP: Yes, there’s a good balance creatively and technically. Of course, we have our own ways of working and personal touches; our own individual sounds and techniques, if you like. Generally speaking though, it’s very natural when it comes to writing music. I feel we have a very clear vision for Shades. Saying that, it’s been very beneficial for the both of us, learning new ways of approaching music and sharing different processes.

Alix Perez’ studio. Click to enter gallery.

When you are together, how do tracks begin?

AP: Generally, we start our tracks and ideas with a free-flow of analog gear. We hit record and play with the gear in the studio. Whether it’s on the modular setup or recording instances of running synths through various pedals and effects. We then run through the recorded material and chop and screw it into coherent parts. We’ll resample a lot of stuff. Variations of effects and so on. The most important part is to have fun and to try to come up with unusual sounds and scapes. For this reason, we don’t chase tracks that aren’t working down the rabbit hole. We don’t waste a lot of time. We move on and then if someone wants to do a ton of detail work on a song, they’ll do that in a solo session.

SD: Yeah, I used to always start with beats but now I generally start by taking a few elements, like say a vocal, or a modular recording, or some other thing, and processing it into a series of sound design sessions, and from which we can build a bass line or a rhythmic element that becomes the backbone of the track. A lot of the time I’ll find an interesting combination of oscillators and effects in Eurorack world and record a long drone at a single pitch, (say, 55hz or A) and then write a melody and play it back from various starting positions in the drone sample. This gives an interesting variation in timbre that can be really useful at the start of a track to generate lots of ideas quickly. We used to mainly start with a beat, but that workflow gets boring and it’s easy to get stuck in old habits like using the same tempo over and over.

What are you looking for from this initial studio jam?

We’re just looking for a vibe, basically. Sometimes you know as soon as you start it’s going to be a banger, but sometimes it takes a lot of work to get there. It’s easy to tell the ones that are going to work because they come together quickly. Sometimes old sketches get recycled or resampled into new works. It’s trivial to bounce a song to the disk and then you have something to resample later if you need raw material. A lot of times I’ll bounce a rough sketch and then load it into Sampler and chop it up, or into Granulator II and completely destroy it and use it for texture!

Can you walk us through one of album tracks?

AP: “The Saga” started as a drum loop on my machine. The rimshot / snare is recorded live through a Neumann TLM 19 then reprocessed with added layers. The kick I drew from my own library and the hats were samples. These were all spliced into a drum rack then jammed on an MPD. Once the drums and groove felt right, I switched the Moog Sub37 on and started jamming bassline ideas. Once I got a decent groove I recorded it via MIDI back into Ableton. I then recorded different instances with filtering and attenuation. I then post processed them and chop and screwed them. The entire intro is actually from another beat that Sander had started which I incorporated into the new project mixed with the new drums. Sander then put his own spin on it and developed the track with added sounds and processing.

SD: Let’s take “Geryon.” I started this track as a drum loop using Famidrums, which is like some drum machine sounds recorded and processed through the NES DPCM chip which makes them extra crunchy. The main drop sounds roughly like it did in the first version. To create the bassline, I recorded some distorted 808 patterns from my Octatrack, and then processed them using granular time stretching algorithms. The high lead is Operator with reverb and distortion. The version I sent Alix was 54 seconds, just a sketch basically, and he took charge of rolling it out to three minutes and creating the dynamics of the track. He created the atmosphere for the intro, and he also added a bunch of his own synthesis, specifically in the last drop where the track opens up and the hits come in all staccato.

Where are you looking for new studio techniques?

SD: I think the techniques are really just a result of playing with something new. Often the first couple of sessions with an instrument or module or software object are the most rewarding because you’re in this discovery phase where the mode of operation isn’t already concretely established in your brain. You are still experimenting because you’re learning. So for us, research and development is the process of finding, acquiring, and learning new gear. Eurorack modular is good for this mode of experimental discovery because when you get a new module, it changes the way your whole setup works and you get to rediscover new aspects of old modules. You get to see old things in a completely new light.

How frequently are you switching your setup to keep this fresh?

SD: For me, I buy about five or six Eurorack modules a year, so not a ton. I prefer to learn each one as much as possible before buying more. With software I’m about the same, I’ll get five or six new audio units a year. I recently moved a bunch of Eurorack effects modules into a rack mount case and installed that next to my audio interface, so I can easily run software sounds through hardware effects. In that chain I have an Erica Synths x Gamechanger Audio Plasma Drive, which is a plasma tube distortion module, Make Noise x Soundhack Morphagene, and Casper x Bastl Dark Matter Feedback Observatory, all of which are unique to hardware and great for mangling boring soft synth sounds or basic drum loops. Another way to keep stuff fresh is to invite other people around to your studio and just let them mess around with your gear, because you might see them use it in a way that you hadn’t thought to try.

AP: Like Sander, I pick wisely when it comes to upgrading studio gear. I like to spend time to find a unit that will process or achieve a certain sound rather than have multiple units doing the same thing variably. With software, I buy a few bits here and there, especially around sale time. I like to use a fair bit of UAD such as the DIstressor, DBX160, LN 1176 and so on. I use Fabfilter and Soundtoys a lot. Hardware wise, Elektron units and a wide array of pedals for FX and Saturation / Distortion. Lots of Synths. Virus TI Polar, MOOG SUB 37, JP 8000, Juno 106, Novation Peak, MS-101, Microkorg XL, MOOG Matriarch (soon to be added).

There must be times when both of you have been required to compromise your instincts based on the other’s. How do you manage times where you’re not in agreement?

AP: If a track feels like it’s being forced or isn’t naturally developing, we usually trash it or go back to it at a later date. Sometimes we might take elements and incorporate it into something new. For example, “The Saga” started as a sketch Sander did and then I merged it into a new project I was working on.

SD: I think for the track to work, we have to generally agree on how everything should sound. If it doesn’t sound right, we’ll usually agree on that too and just scrap the track or use it as the basis for a new track.

How do you feel Shades informs your own solo productions, if at all?

AP: I’ve learned some unusual stuff from Sander, like weird sound design techniques that I wouldn’t have thought of using before. He’s taught me a lot about Ableton. Prior to working together, I was still working on Logic and thought it was a good time to make the shift. I haven’t really looked back since and love working with [Ableton] Live. It’s opened a lot of doors and different ways of working.

SD: I think I’ve learned techniques from Alix that have made be a better, faster producer. He has taught me to be faster in the studio and keep ideas fresh. It’s a lot easier to follow through to the final mix on a track if you’re both excited about it, and if the track takes too long you lose that initial spark.

How do you maintain this initial spark when you’re working in different time zones?

AP: Whatever progress the other makes on a track tends to keep us interested. It’s like, we have the initial spark and then there’s a secondary spark from the new possibilities created when the other iterates on the initial idea. We bounce tunes a lot so we can listen to them, and sometimes we’ll end up resampling old ideas to make new tunes.

Do you master yourselves?

We master tunes to play out, usually with pretty minimal mastering. We accomplish most of the loudness in the mix down phase. For release, we usually use Bob Macc at Subvert Central.

What’s next, in terms of releases?

We definitely have a bunch of stuff we’re working on but it’s not at a stage where we can talk about it yet.

All Eprom photos: Tyler Hill.