In The Studio: John Tejada

The Palette Recordings label boss takes XLR8R into his home to learn more about his creative processes.

In The Studio: John Tejada

The Palette Recordings label boss takes XLR8R into his home to learn more about his creative processes.

When we were first told we’d have the chance to peek inside the constantly evolving home studio of Palette Recordings label boss John Tejada, there was only one way to meet the opportunity: with respect and reverence. Considering the lineage of sounds that have reverberated through his studio walls in Sherman Oaks, CA, we realized that this is the working space responsible for influential tracks like “The End of it All,” “Unstable Condition,” and “Paranoia.” Consider the fact that Tejada has released more than a combined 50 EPs and full-length LPs since 1996 on just his own label; package that with his history with revered labels like 7th City, Immigrant, and Kompakt; then put it all together with his innumerable remix credits and EP splits with a variety of artists over the years—only then will you finally start to hone in on the scope of producer that we are dealing with.

During our time with Tejada, it became abundantly clear that the man is an absolute repository for advanced technical production processes and track development. It’s easy to see how he has so closely aligned himself with long-time producer friends like Detroit’s Daniel Bell, to the point where he is the only person that Bell trusts to perform live percussion during his sets. With a new split EP coming out in January with Tin Man on Acid Test, and a new record with Arian Leviste scheduled for release on Areal later this year, it should be no surprise that we were excited to visit him at home for another edition of In the Studio.

How long have you been in this studio?

I’ve actually been in this space for nine years now.

Have you had this specific setup for longer than that? Is it an incarnation of a previous studio?

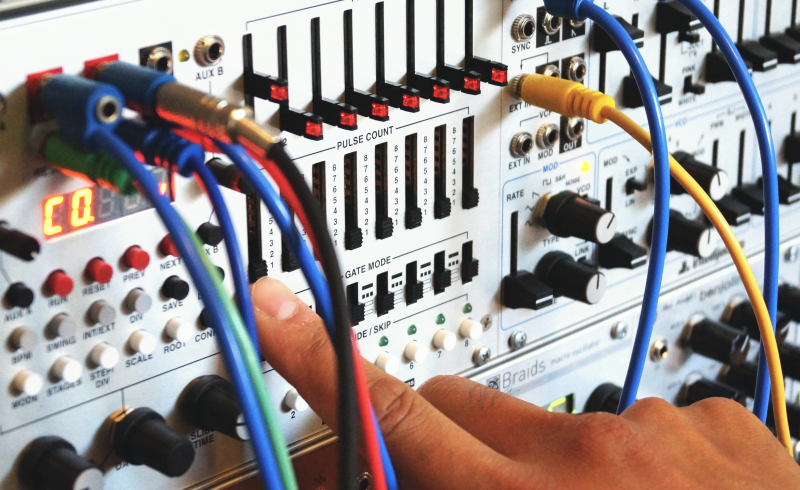

It has changed a lot over the years—whether that’s been a changing of a console, or bringing it back and getting rid of it again. I think what ends up happening is that I try to always get it to a place where everything has a purpose, and even then I think I could scale it down even further. I’ve had fantasies about doing really simple things, and I think if I moved to a different room, I would just start from scratch and just do something really stripped down. Like with the Intellijel Metropolis and the Atlantis, putting those into a case and just going somewhere with headphones and just really getting lost in the gear. When you bring more elements into play, you almost feel guilty for not using them. Picking the right tools is the best way for me to get things done. Obviously it’s still super-fun to get new toys and try new things—but I think that’s part of the process, finding the type of thing that works and the type of thing that I actually need. Do I really need three things that do the same thing?

That’s one thing that I’ve heard a lot of artists talk about in regards to their studios: There’s an internal conflict in that they don’t really use a piece that much and that they probably should switch it out, but that they have a certain attachment to the gear.

Yeah like the old Rolands and those pieces. Mine (Roland 808) is a bit modified, but there’s just something about dialing in the right sound for exactly what you’re working on, and I find it fun to really process them too. I find that most of the drum sounds are very similar to the Roland, but maybe they are lacking a certain aspect of it. But then if you can take those sounds and process them in new interesting ways, then you might find out that that’s exactly what you want. The Roland stuff just seems to have a certain meat to it that others don’t. Like others will sound good, but they don’t seem to smack you in the chest in the same way.

Yeah, exactly! I recently read that, for you, a similar internal conflict had been happening in regards to new production processes that you’ve been utilizing. You’ve been sampling small chunks of sound rather than recording long continuous lines, and you’ve been feeling a little conflicted as to whether you should be doing it that way, even though you found a lot of enjoyment and fresh inspiration from it.

I think a lot of it is just getting to grips with who you are and things that come naturally to you. It’s important that you do not throw this away because that’s your I.D.—that’s your print, your natural talent. It’s always easy to want to strive for the unknown and make something complicated, but then when you just kind of do something and get in the zone and it flows freely, that’s the stuff where people are like “Oh yeah, that’s really cool.” I’ve kind of been embracing that more and more. I’ve been doing really long synth takes and, instead of just letting that play front to back, I’ve been putting it into a program called ReNoise and going through and pulling bits out of it. It makes it really fun, like the way that older samplers used to be fun, because I never quite know what to do when I have a session of just chunks of audio. It’s makes it hard to manipulate it like that. Like with the old tracker guys, when you hear their stuff, you’re like “How the hell did they do that?” And it’s actually not that hard and really fun.

Besides the Intellijel Metropolis and Atlantis that you mentioned, what are some of the key pieces of gear that you find yourself always going back to, or always having that constant connection with?

The Elektron machines are really special. They take old ideas from the heritage pieces, but they are more forward-thinking. One of my favorite pieces, and it’s actually not in the studio at the moment, is still my Machinedrum. The Elektron pieces are really unique because they are multi-purpose pieces. Like the Analog Four, or Keys—they can do a lot of CV and audio processing, which is quite awesome, but I think the Machindrum still has a huge bit of magic, especially with the live re-sampling.

For poly, the CODE is a great because it’s a true poly, where everything is per voice and really massive sounding. The SH7 is the all encompassing, classic Roland mono synth. Along the lines of a System-100, with a little bit of the later 101. For me, that can quite spacey, and Moogy, and big.

Is your current live set-up still all Elektron pieces?

Yeah, it is. When I travel, they just have this great bag where you can fit three of them in it. I don’t know if it’s because I’m doing something wrong, but I usually have to squeeze into really tight spaces at gigs. I think also, because I do a lot of DJ work, that somehow it’s not clear that they need to have a stage for the live thing. But when I drive to a gig, that’s when I can bring out some of the big boys, like the 909. To get that on a PA is huge. It’s kinda like the Ludwig drum set. There’s just something about the PA that you don’t get in the studio. Sometimes when you’re recording things, like with an acoustic drum kit for example, you can treat it and use all these pre-amps and compressors, gating, reverb, blah blah blah. But when you hear the band playing live, it’s like “Oh that kit just sounds fucking great!” And there’s not a lot done to it. I think the 909 is similar in that way, when it’s on a PA and you’ve got the room, and it’s pushing air, there’s just something super magical about it. I remember Orbital in the early ’90s, just having that raw 909, or Daft Punk at the Mayan in ’95, like “God, that just kicks so hard.” But then in the studio, it’s just like a thud.

At MUTEK in Montreal, you played live drums with Daniel Bell—which was very impressive, by the way. Do you have a background in drumming? And how did that collaboration come about?

I do have a background in drumming. I discovered drums when I was eight when I moved to the states back in ’82. The place we were living at, my cousin was there and he had a kit and all these Led Zeppelin tapes, and I remember seeing him play and thinking, “I can do that.” So when he was away, I would just put on Led Zeppelin IV and just try to figure it out.

But Dan started doing that as an idea before I was doing it with him. He had two people, this guy Hanno on drums and Stefan Betke (a.k.a. Pole) doing some synth bits. From that, he realized he liked the percussion aspect better. Dan and I go way back; I always refer to him as my big brother, which he kinda hates. I sometimes ask him for advice, and he can’t deal with it. But we get on really well and we’ve known each other for around 20 years, so we just trust each other. It was actually an easy process, and the first time we did it was at the Detroit Movement Festival last year. I came out early and just took some notes of what he likes and what he doesn’t like, because there’s certain sounds he doesn’t want played by anyone else, because it doesn’t fit his ear. And there’s certain things that do work really well for him—but in a way, it’s like I’m just a percussionist. I don’t have a kick drum, which kinda feels like I have one hand strapped behind my back. But we make it work.

You could definitely see the deep connection between the two of you on stage. Not once did you look at each other but it all worked perfectly.

Yeah, I think we just connect on our timing and rhythm really well. You know, that unspoken thing. There was one moment where we both were like, “Woah, we’ve never done that before”—it was really cool. We can kinda speak to each other without saying much.

It was actually hard to follow the set before us, which was basically the best thing I had seen all year, Atom™ and Tobias. They fucking crushed it, and it was very improvisational. I would be too scared to do what they were doing. I mean, I do a bit of improv with the machines, but their shit was all improv. And it was so fucking tight. It was great. Best thing I saw all year, it was bad-ass.

How do you approach your live set? Do you go in with a loose framework, like a skeleton, that allows bits of improv? Or is it more structured throughout?

I’ll try to explain it in the best way possible. I’ve had different iterations over the years, but what I do now is use the Octatrack as my Ableton-esqe workstation. So starting here in the studio, I send sync to everything and use my Elektron toys to get paint-splatter writing going. It’s not thinking too much, just jamming. The Octatrack is quite good at capturing things, so I don’t use my computer at all. So I capture things into the record buffers, and I assign them to tracks—just things that work together. I’ll do that for eight channels and will set it up so not everything plays at once at first—because on the Octatrack, it’s not like the typical Roland, 16 patterns with banks. What you have is 16 banks and, within each of those banks, you have 16 patterns—so, each bank is essentially a song. So within a bank I can have 16 variations, and the great thing about the Elektron gear is that they do these things called parameter locks. So per line, you can copy in parameters and info, and it makes it quite easy to change parameters just for that one step.

So that makes it easy to go into record mode while I’m playing and do some parameter locks, or change some pitches and play positions, filters, effects, etc. I load up the Octatrack with as much as I can—essentially 16 banks, or 16 “songs,” of loose material. When I play with the Octatrack, if I don’t reload what was in it before, it all gets saved—so sometimes if I play a couple of weekends in a row and keep not saving, the set becomes quite mutated in a way. But I always use the audio stems that I record here in the studio as the basis of the set. I used to have everything quite tied to songs, but now that’s what I’m trying to get away from…the way something starts, or the drum sounds. So now the drum sounds aren’t tied to any of the pieces, so it’s quite loose. And like I said, sometimes I’ll bring the Roland and not the Elektron Rytm, so it’ll be totally different drums. For some of the songs I perform that have been released, I kept them skeletal. I’ll know the melodies, so I’ll recreate it here and get it sounding somewhat like the track, but I’ll include loads of different pieces so it keeps it fresh. It’s the most free and fun way I’ve ever done my live set in the sense of constantly updating it. When I feel some parts are feeling flat, or batches of sounds are feeling flat, I’ll hook up the Octatrack again, sync everything up, goof around, have everything going to the record buffers, and load them up and see how it sounds. If it’s good, then that replaces what was there before. It’s kind of something that’s not meant to be listened to outside of the live realm. Like that dynamic I spoke of where certain things sound great on a PA, but need more work when they are recorded.

In regards to production, where do you find your inspiration? Do you go in with clear ideas, or is it more a jam-based approach?

For me, usually, there’s some idea of what I want something to sound like, and if it happens correctly, then the other pieces will fit around it quite easily. But if I’m just struggling to even start, then that’s not a happy feeling. The happy feeling is having that one thing where you’re like, ‘Oh shit, that’s really cool,” and then you can build everything around it. That’s generally how it goes.

You mentioned earlier that you’d like to go somewhere away from the studio, with a few pieces of gear, some headphones, and just jam. Do you do that often? Like in the mountains, in the desert or to the ocean, to get weird and find new inspiration?

Yeah, well, it’s something that is becoming more realistic again for me. It’s fun to just load up like the Octatrack and go through it later and make sense of it. It’s called ReNoise. It’s based on a tracker, but there’s loads of new tech in it that rivals modern DAWS. So when you’re using a computer, what have you got? You’ve got samples of audio. You have synthesis in the computer with VSTs and whatnot, but once it’s rendered, everything is audio—so you really just have code and audio. At first, it’s kind of frightening when you make all the other stuff go away, but once you embrace it, it’s like “Ok, this is audio. What am I going to do with this audio?” And you can zero in on things and manipulate them very expressively, as opposed to Pro Tools, or Logic, or Ableton, where you have all these endless options. Some people are great at that, but I kind of suck at it. This program does away with third-party tools, so you think how to make it move in the way that you want. At first it’s daunting, but once you embrace it, it’s great. It’s like with Aphex Twin and his really open comments on Soundcloud. Someone asked him about Drukqs, and he said that it’s all tracker-based, and I was thought “I knew it!” Because I would get into this program and there’s a few really obvious signs of the way audio moves, and there are certain things you can do that would be very complicated otherwise. That whole record of his is essentially a tracker record. That’s essentially taking audio and manipulating it, so I feel very happy in loading up the Octatrack with bits that I do here, or loading up ReNoise, and just have these free running bits of audio to go through, instead of trying to make all these traditional band-like “takes.” When I first got into stuff, you were quite limited with sample time. Or with an MPC for example, you’d have things on the hard drive and would take it somewhere and just really just mess with what you have, and I kinda miss that.

In our In The Studio piece with Adrian Younge, he stated that in regards to mixing, he “mixes wrong to get the right sound”—ignoring those traditional rules, or conventions—trusting your gut and what you think a final mixdown should sound like, and keeping a highly focused vision to the end. What are your thoughts on this?

Yeah, I mean, people always fight about this largely because there are so many products trying to be sold these days. People will try to guilt you into thinking that you’re doing things wrong, and I think that’s a really negative thing these days. I don’t think anything is wrong unless it sounds wrong, and then it’s pretty obvious. I think that people can be nitpicky about something being lo-fi or whatever, but you can always tell if something sounds good or bad.

There’s all this weird fighting about how something is supposed to happen. I mean, you have a certain room of frequencies to shove all your music into, and then you try to make it fit. Even if you make huge boosts in something, then you’re essentially dipping out loads of the rest, so it might make more sense to dip out things rather than maybe causing aliasing by doing these massive boosts. It always just comes back to if it’s sounding good you know? So much of what people are after these days is because of people experimenting—people doing things that they weren’t supposed to do. Most of the things that influence me happened in the early ’80s with the misuse of samplers. And at the time you had to be really brave, and I always had this thought, that in order to be original, you might lose some friends. Like seriously. And that’s what a lot of people went through.

That’s a great segue into the analog-versus-digital debate—that thought process that you can’t get the same sounds from a plug-in as you can get from the analog world. What are your thoughts?

Oh, that’s all bullshit. It’s preference. It’s the same with preference in music. My experience is from when I was like 17 to 21 years old, and that’s what is going to shape me no matter what. Where I came from, you didn’t have the digital options like we do now. So my preference is going to be the linking of gear and having it play, or having a simplified or limited feeling with what I’m doing with samplers. And that’s my preference. If somebody comes along now, they’re probably not going to experience that—and that’s fine, because that’s their preference. You know, it might be using an iPad, it doesn’t really matter. Again, it all goes back to marketing, this fear-mongering with what you need to have. It always reminds me of this Patton Oswalt skit, where he makes fun of people who wanna do natural births, because that’s the way that people had to do it back in the wild west or whatever. And he’s like “Yeah, and you know what those people were dreaming of? Hospitals!”

They just didn’t have any of this shit. Like I recently read an article by an engineer named Andrew Shepz, and he said that he’s working all in the box these days. I was completely blown away! He was like “I’ve been there, whatever, it just works for me now.” And that’s it, it’s what works for you. It’s what makes you comfortable. It’s just preferences. People are always fighting over what’s the best, but it always comes back to personal preference.

John Tejada on tour:

Nov 13 2015 – Paris – Badaboum – live

Nov 14 2015 – Cologne – Gewölbe – live

Nov 15 2015 – Milan – D.O.G.S. – DJ set

Nov 18 2015 – Angers – Le Carré – DJ set

Nov 20 2015 – Bilbao – Fever – Dj, Guggenheim Museum – live