Vanguard: Jean-Michel Jarre

One of modern electronic music's founding fathers fills us in on his sprawling collaborative project, 'Electronica 1: The Time Machine.'

Vanguard: Jean-Michel Jarre

One of modern electronic music's founding fathers fills us in on his sprawling collaborative project, 'Electronica 1: The Time Machine.'

“There’s always that bloody question,” he says, a hint of resignation barely discernible in his urbane, heavily accented voice. “‘Why do are you making music with all these strange machines?'” It’s a query that probably made sense in 1971, when Jean-Michel Jarre—in his early 20s and working under Pierre Schaeffer in the Group for Musical Research—kicked off his musical career with the release of “La Cage,” a track that merged his studies in musique concrète with a touch, just a touch, of pop sensibilities. That record originally sold all of 117 copies—and though the electronically-oriented likes of Kraftwerk, Mike Oldfield and Tangerine Dream had begun to make inroads into the popular consciousness, the question probably still made sense a few years later when, after doing studio work for Françoise Hardy, Christophe, Patrick Juvet and others, he was shopping his debut album, Oxygène, to record labels.

Released in 1976, Oxygène—an epic, cosmic set of graceful melodic ambiance—eventually sold 12 million copies and, as much as any other record, proved that electronic music could succeed in the pop market. Jarre’s had a long and storied career since; among many, many other claims to fame, he was the first Western artist to be invited to play in post-Mao China, and he collaborated with NASA for a Houston concert that attracted 1.3 million attendees, earning himself a second Guinness World Record. (The first was for a show at the Place de la Concorde in Paris, with an audience of a mere one million.) He’s since gone on to sell over 80 million records, but still that question nags him—which might explain why he’s just released the ambitious Electronica 1: The Time Machine. The 16-track album is Jarre’s attempt to tell the story of electronic music’s history, featuring collaborations ranging from pioneers along the lines of Laurie Anderson, Vince Clarke, John Carpenter and the aforementioned Tangerine Dream (including that band’s late Edgar Froese) through to modern-day behemoths like Armin van Buuren. XLR8R recently caught up with the iconic producer via Skype at his Parisian home, and he graciously took the time to fill us in on the new album, and give us his views on the musical universe that he helped create.

Back when you were making songs like “La Cage” in the very early ‘70s, did you have any clue that electronic music would become the force that it is today?

Absolutely. I’ve always been convinced that electronic music would become the major way of doing music, for a few different reasons. First, electronic music is not a genre, like punk or rock or hip-hop. When I started, it was a new way to conceive of music composition and music production. This idea of approaching music not only in terms of notes and harmonies, but also in terms of sounds and noise, was so radically different than what we had before. I knew it would create a big change.

And you were aware that this change would take place within popular music? You were already working with artists like Patrick Juvet by the mid-’70s, so it seems you figured that out pretty quickly.

When I was at the Group for Musical Research, with this idea of discovering electronic music, I quickly realized that that it was a very interesting and exciting approach to music, but I also saw that it was very intellectual and quite dogmatic. I saw that outside of that intellectual side, you had people like Soft Machine and Pink Floyd who were using elements of electronic music in a different way—within the pop culture. And when I left the Group for Musical Research, I really started discovered this world of pop music, with big studios that the record companies would supply. For me, that was like the grail!

I started to explore what could be done in all different ways—music for movies, for television, for rock and pop artists and everything. I started collaboration with people like Françoise Hardy and Christophe and Patrick Juvet, so that I could start creating what I had in mind by using electronics in normal pop production. At the same time, I was becoming convinced that what I really wanted to do was to create a bridge between experimental music and pop music.

At that time, you were one of only a handful of people working towards that goal, right?

There were not a lot of people doing it. We were considered like a bunch of aliens! Everyone thought we were crazy for working with machines; nobody considered them to be musical instruments. Even Oxygène—before that was released, it had been rejected by almost every record company. They asked, “What is this? There is no singer; there is no drama!” It was not that easy to get it released, because it was considered to be so absolutely different from the format of the time.

It must have felt pretty good to prove them so wrong.

Yeah!

Jumping ahead a bit—almost four decades—and now you have Electronica 1: The Time Machine. It’s meant to be your look at the history of electronic music, right?

Yes, but the idea for the album was originally more personal. It started with the desire to gather people around me who have been inspirations to me. And then it did become a way to look at the evolution of the electronic-music scene, and also the evolution of the technology over the decades of that scene since I started. But I didn’t want to work with these people in the way that’s become a feature of collaborations, where you just send files through cyberspace, and someone will just do some toplines for it—vocals or melodies or whatever—and you never meet them, or even talk to them. Most of the time, that’s just done more for marketing reasons that anything else.

You were hoping for more in the way of true collaboration?

I really wanted to meet with people physically. I traveled, a lot, to meet with people. The surprising thing is that everybody who I wanted to have on this project said yes!

How did the collaborations work?

We’d start by me writing some pieces of music in the mode of the collaborator, as a starting point for working together. These starting points were different for each of them, in terms of sound and inspiration. It was a way of creating a bridge between all of us—not just be and them, but from Tangerine Dream to Gesaffelstein, for instance, or from Air to Massive Attack, or from Moby to Fuck Buttons. We ended up with two hours of music, which is why there is going to be two separate albums. The second half will be released in spring of next year. All together, there have been 30 collaborators, and I had no idea that I would be able to get this kind of range of people. In electronic music, there are really no boundaries anymore. It’s everywhere!

Did you feel at home while you were working in all these different styles?

For me, it is all one family. It’s a family with a past, but more than just its heritage, it’s a family with a future as well.

And its really all just music, anyway, right? Do you even feel that there is a need to split everything up into genres?

I totally agree with you; it’s all music. Actually, for me, electronic music is the classical music of the 21st century. When you talk about classical music, what does that mean? The word classical covers so many different genres. That’s why I have collaborators as different as Armin van Buuren and Pete Townsend, or from Lang Lang to John Carpenter. In the second one, we’ll have people like David Lynch and Gary Numan, too. People could ask, what’s the link?

“We’re all geeks! We’re all digital-analog geeks.”

Okay, we’ll ask: What’s the link?

The link is that greed, that appetite, for technology. We’re all geeks! We’re all digital-analog geeks.

You mentioned Pete Townsend. Some people might find him an unusual person to be working with on an electronic-music album—but they’re about forgetting songs like “Baba O’Riley.”

Absolutely! You have to remember that “Baba O’Riley” is in part a tribute to Terry Riley. Around the time of that song, I was an assistant at a recording studio in the outskirts of Paris called the Château d’Hérouville, where lots of big artists from that time would record. I was preparing sequences for Terry Riley’s album at that studio—so there is a link on that private level with Pete. Also, Pete is a fantastic conceiver; he’s always coming up with concepts that will push the boundaries of rock. I mean, he’s the creator of the rock opera as an art form!

I’m guessing that you had met Tangerine Dream’s Edgar Froese before, but it’s so nice that you got to work with him for this album shortly before he passed away.

Of course, yes. Funnily enough, we had never really met before. We had crossed paths, but only very briefly. But of course, Tangerine Dream was quite high in my mind, for obvious reasons. To work together, I left Paris for Vienna, then I took a car for 150 miles to where he lives, and once we really met, we felt live we were friends forever. We spent a lot of time talking about music. When I shared the music I had prepared, we just got to work on it, and it went really well. After I left, Edgar’s wife said, “You have no idea how much pleasure and excitement you gave to Edgar.” Making the effort to come to his place, to his studio, really made him happy. In the age of the Internet, we are sometimes too lazy to do that.

You said earlier that you really didn’t want to just send files back and forth.

No, and that didn’t happen at all. A very important part of the Electronica project was to travel physically to meet and spend time with people. It makes such a difference. Moby, for instance, said “You know, I’ve done some collaborations—and this is the first time that someone came to my studio to collaborate. It changes everything!” It can be difficult for people to open their doors and confront people with your rituals, to share your secrets, your strengths and your weaknesses. It’s something special. And that changes everything.

Did you go to visit all of your collaborators, or did some of them come to you?

It worked both ways. For instance, with Air, we joined forces in my record studio in Paris. It was an interesting with Air. There is oxygen in air, of course, so there is a big link between us. But for the song we did together, we figured why not use instruments from the many decades of electronic music? So we start the track with old oscillators; then the first loop is done with razor blade and cellotape, editing half notes and quarter notes and eight notes, calculating the length of each piece of tape in function with the speed of the tape. Then we took that big loop and set it up, using a mike stand, so that you have it playing indefinitely over the tape head of the recorder. Then we moved into the first drum machines and the first analog synthesizers like the Moog, then to the first polyphonic synthesizers, then the first samplers like the Fairlight, then the big digital machines—and then, the last sound is made on an iPad.

Wow—not exactly a throwaway track, is it?

And it was fun to do! We didn’t mix it all chronologically, and for people who don’t know what we are talking about, it will just be a piece of music. But if you understand, it symbolizes the concepts of Electronica.

Was there anybody that particularly surprised you in the way that they worked in the studio?

If I say all of them, I hope that you don’t think that I am joking. I chose these people by instinct, but they really turned out to be quite special in their own ways. They are all…not of trends, I guess you could say. People like M83, Massive Attack, Gary Numan, or Fuck Buttons—they’re all slightly separate from what I would call “the system.” And it was actually a kind of learning process for me, working with the collaborators; I mean, going from working with Armin van Buuren to Lang Lang is like going from the earth to the moon! But they all have this instinct of innocence, and a desire for experimentation.

The same could perhaps be said for you, even after selling so many millions of records over the course of your career. You probably don’t really need to do this anymore. What keeps you motivated? What keeps bringing you back into the studio at all?

You know, there’s always that bloody question: “Why do are you making music with all these strange machines?” I was recently realizing that I’ve probably spent 80 percent of my life in studios! It’s very difficult to do that and still have a private life; it’s very difficult to do anything else. It would have been great to have chosen another direction—maybe I could have done astrophysics, or maybe I could have been a cook. But I do this because I have no other choice. It’s an addiction—a positive addiction, but still an addiction, and you don’t get rid of an addiction. It’s not a matter of thinking, oh, I’ve done this and I’ve done that so I’m happy with myself.

“The creative process is a constant battle between creation and hope.”

But, considering your lengthy career, you must at least be satisfied, right?

Well, yes, but the creative process is a constant battle between creation and hope. You never really reach what you want to achieve, and you hope that next time will be better than the previous time, and you go on and on. As an artist, you have this ideal, and your whole life is spent getting closer and closer to that idea. That is the beauty of art, and the beauty of being an artist.

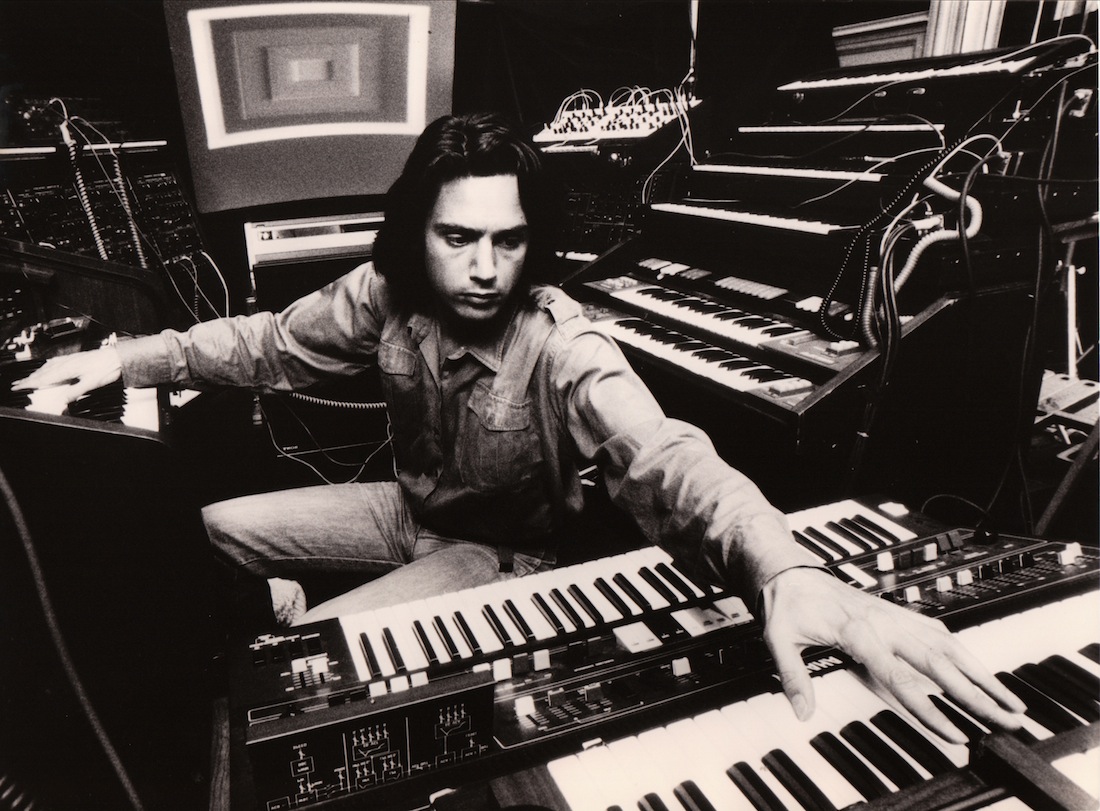

Top photo: Jens Koch