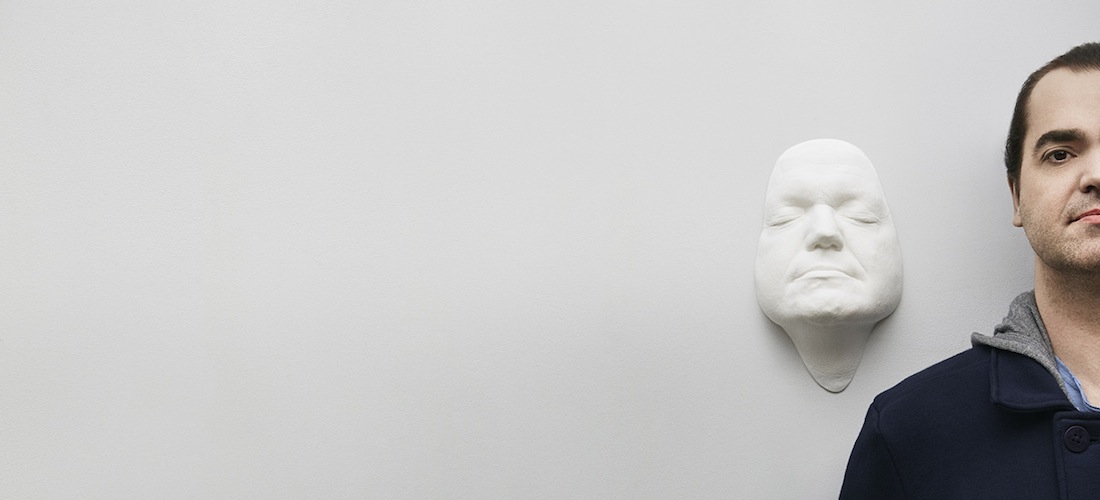

Q&A: St Germain

Ludovic Navarre breaks his silence with a heady brew of house, jazz, blues and Malian sounds.

Q&A: St Germain

Ludovic Navarre breaks his silence with a heady brew of house, jazz, blues and Malian sounds.

You may not recognize the name Ludovic Navarre—but chances are good that you are intimately familiar with the man’s tunes, for Nararre is one and the same as St Germain. And even if you don’t think you know the music of St Germain…well, you probably do if you’ve been to a club in the past 20 years, or maybe even just wandered into a boutique or café that lures its customers in with lush and atmospheric tunes. The French producer broke onto the scene via 1993’s French Traxx and Motherland EPs, released on Laurent Garnier’s F Communications label, but it was in 1995 that the St Germain sound—a dreamy, atmospheric and emotive amalgam of house, jazz and blues—really hit home. That was the year that saw the release of the million-selling Boulevard album and the brilliant single “Alabama Blues,” a song that fully displayed both Nararre’s knack for well-chosen vocal samples (that’s Lightnin’ Hopkins’s “Stranger Here” providing the hook) and his talent for selecting sympathetic remixers (Todd Edwards, Black Science Orchestra, Shazz, Rae & Christian, and Wax Doctor are among those who supplied mixes).

More world-conquering LPs and singles followed—including, of course, 2000’s hypnotic stunner “Rose Rouge,” the inescapable “I want you to get together” cut that sampled its vocals from Marlena Shaw’s live version of “Woman of the Ghetto.” It was, and is, one of house music’s most omnipresent numbers—any tune that can happily sit in both acid-jazz compilations and tough techno sets (Anthony Parasole played it at the recent Sustain-Release fest, for instance) obviously has wide-ranging appeal. The song featured on the massive Tourist album, released on Blue Note, and was soon followed by 2001’sSo Flute EP, a exhaustive series of live dates, and a Navarre-produced album, Memento, from his trumpeter, Seol. And then—nothing. At least till now: This past spring, a new St Germain single, “Real Blues,” with remixes from Atjazz and Terry Laird, hit the shops. And it’s the same St Germain that we remember, with one major addition: Navarre has added the music of Mali, specifically the haunting sounds of the West African country’s hunting ceremonies, into his vibrant mix of live instrumentation, electronics and samples. A self-titled St Germain album, one that continues further cements his love affair for Malian-tinged music, was released on October 9; XLR8R recently had the chance to speak with Navarre through an interpreter as he prepared for an about-to-start European tour, with Navarre joined onstage by eight musicians and singers from musicians and singers from the African diaspora.

This is your first full album in 15 years, and the first release under the St Germain name in almost as long. How have you been spending your time over this past decade and a half?

First of all, after touring for about two years, and after about 300 dates, I just had to stop and take a break. My head was full! So I took just stopped, for about six months. Then in 2004, I recorded the album by my trumpet player; in 2005 I did a concert in China; then, finally, in 2006, I started thinking about what I would do for the next album.

Even that was nine years ago!

It was a long process. I spent the years 2006 and 2007 as what I call an “audio tourist.” I always have the same influences, jazz and soul music—but I wasn’t happy. I wasn’t excited by it, so I started wondering what I could do that would be new and exciting. Finally, in 2007, I thought that this was maybe the time to start mixing in some sounds from Africa. I started looking towards Nigeria and Afrobeat, and I made some attempts with that—but I still wasn’t happy. So in 2008 and 2009, I started making some further attempts, this time with music from Ghana. It was really complicated.

How so?

Just finding the people to do it was, and getting it done. Finally, I gave up on that idea. Then, in 2009 and 2010, I started looking around on the Internet for inspiration, and I started looking toward Mali. I was a bit familiar with music from Mali, but it was when I discovered the music of Malian hunters that it clicked. At last, it started to fall into place. And then I finally started working on this album.

Why do you think the Malian influences clicked more than the the music of Ghana or Nigeria? Was there something specific about that music that spoke to you?

I really think it’s the blues aspect of the music. It’s comes through stronger in the music from Mali than the other countries.

And what is it about the blues that does it for you? There’s always such a strong current of it running through your music.

Well, it’s very hypnotic music. It puts you in a trance, and then gives you these little jolts that bring you out of that trance. There’s an oscillation that goes back and forth between the hypnotic aspects and the peaks. Malian music has that same feel for me.

A lot of your music, from 1993’s French Traxx and Motherland EPs through to “Alabama Blues,” “Rose Rouge” and now the new album, are in large part defined by what you choose for your vocal samples. What’s your secret to picking the right vocal?

Honestly, it’s more just by feeling than any kind of specific process. I’ll make an instrumental track, and I’ll think, hmm, what would work here? And then when I start thinking about what voice to use, it’s more the texture of the voice than anything else. People like Lightnin’ Hopkins have very unique voices; I couldn’t just use any old singer for my music. There has to be a real identity to the voice.

“I like to get remixers who are going to be respectful of the original work in some way, and respect the universe that I’m from. And, of course, I want people who aren’t interested in putting out some vulgar dance track.”

You’ve always managed to get great remix work done for your singles. How do you go about selecting your remixers?

That’s pretty simple: I just look for artists and DJs that I like and that I listen too. Atjazz, for instance, has had many remixes over the years, and almost all of them are really good—sometimes better than the originals. So I met him and asked him to do it, but I told him, “Take it easy—don’t do something better than my version!” But overall, I like to get remixers who are going to be respectful of the original work in some way, and respect the universe that I’m from. And, of course, I want people who aren’t interested in putting out some vulgar dance track.

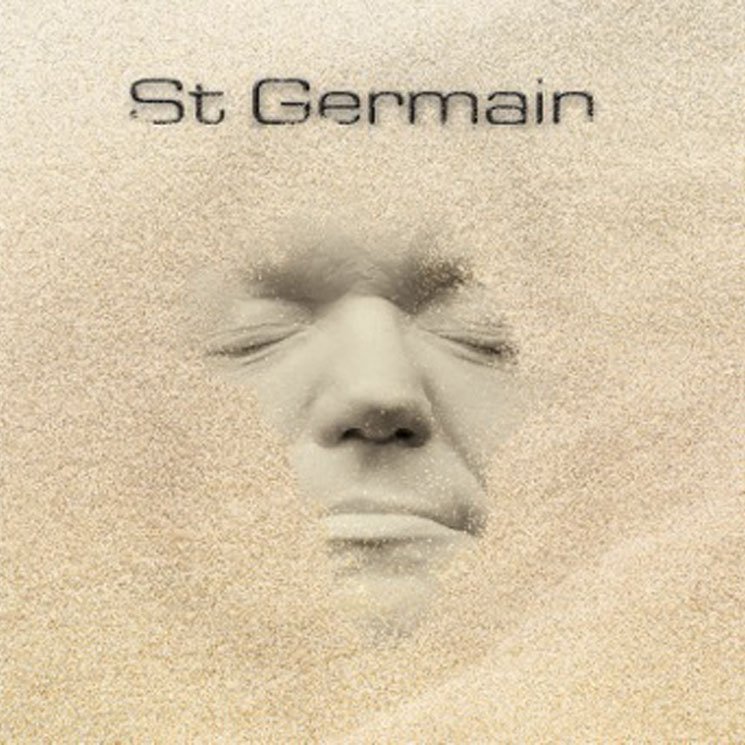

Finally, that mask on the record cover and the video—is that your face?

Yes, it is!

Top photo: Benoit Peverelli