Record Store Week: Rubadub

All week long, XLR8R will be taking a closer look at some of our favorite […]

Record Store Week: Rubadub

All week long, XLR8R will be taking a closer look at some of our favorite […]

All week long, XLR8R will be taking a closer look at some of our favorite record shops from around the globe. Check out the entire ‘Record Store Week’ series here.

In April last year, around 300 people gathered in Glasgow city center for an unusual party. People brought bottles of champagne and wore party hats to George Square, chanting “ding dong, the witch is dead,” and “Maggie Maggie Maggie, dead dead dead.” In other parts of Britain, on the same day, people played instruments, let off party streamers and drank milk (it’s a long story) while rejoicing in similar fashion. They were celebrating the death of Baroness Margaret Thatcher, the former British prime minister and a pariah figure for the country’s working classes. Thatcher is hated more in Scotland’s west coast than perhaps any other region, but she wasn’t all bad: she was also the inspiration for setting up Rubadub, a dance music institution in Scotland that celebrates its 22nd birthday this year.

Martin McKay, the shop’s founder, dreamt of escaping a job he hated in his early 20s to open up a record store. “I worked in an office with the council, pretty mundane office work. Poll Tax actually [a Thatcher policy introduced to Scotland in the late 1980s]. Poll Tax registration, so that’ll give you an idea. I was rebelling against it while I worked for it; I was out protesting against it, but to be honest, it cost me a bloody fortune! But that was the initial spur to get me to go and start a record shop.”

Now encompassing a dedicated music equipment section and a distribution business, Rubadub has grown to be one of Scotland’s most vital underground institutions. It’s also one of its least visible. When Rubadub throws a party, its name is rarely on the flyer. The shop has been pivotal to the various successes of three major Glasgow-based labels: Numbers, Dixon Avenue Basement Jams, and All Caps, but there is rarely any mention of the shop in the promo materials. And though Rubadub is bookended by Jamaica Street’s Sub Club and a busy shopping center, it feels removed from the retail frenzy of Buchanan Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, and the seasonal Eurotrance amusement park in neighbouring St. Enoch Square. “It’s just a wee lynchpin, an understated sort of [thing],” says McKay. “I’m not looking to be the big overseeing bubble. It’s just a wee thing in the middle that [everything] shoots away from.”

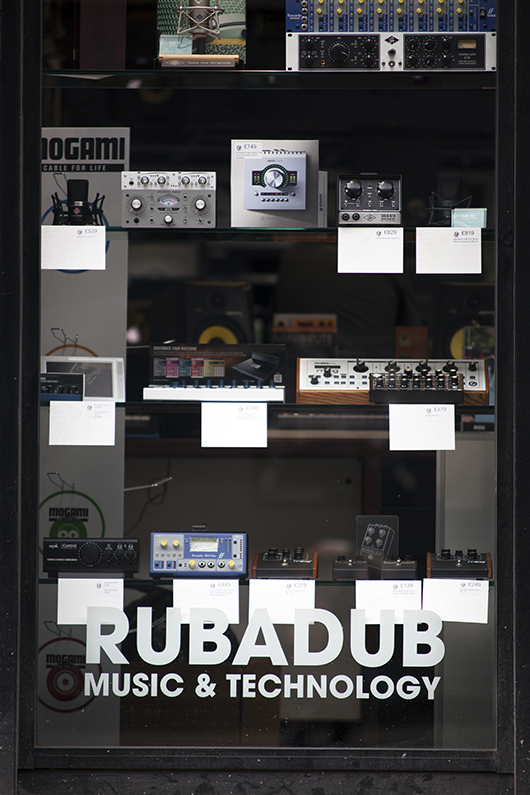

Walking into Rubadub, the first thing customers tend to notice isn’t the shop’s assortment of records, but its extensive collection of synths. There’s a Korg MS-20 and an Arturia MicroBrute at the front; behind that is a Eurorack modular synth, housed in a wood-finished Lamond Designs casing. To the right is an extensive Native Instruments Maschine set-up with a Mac computer. The walls are covered with monitors, DJ bags, microphones, MPCs, and MIDI controllers. It’s an array that suggests Rubadub’s equipment store has helped nurtured the city’s producers as much as its records have done the same for Glasgow’s DJs and music heads.

“It’s definitely, in my opinion, been a hub for people,” says Dan Lurinsky, the shop’s manager and co-founder of Dixon Avenue Basement Jams. “Before people started producing records, for instance, they would come in and buy their records from us. The good thing about Rubadub, from every angle, is we’re all deeply in love with the music and everything about it. In the shop just now, you’ve got big Alex [Jurczyk], who’s mad for the modular synths. You can just tell as soon as he starts talking about it, and it’s really easy for him to get other people interested in it, just with his enthusiasm. Same with anyone in the shop: whether it’s about records or equipment, people come in asking for advice or whatever, we’re always about. And obviously, over the years, lots of people have; your Rusties, your HudMos, all these guys that are doing pretty well at the moment.”

What little white space remains on the shop’s surfaces is covered in flyers for upcoming shows from Tuff City Kids, Theo Parrish, and Chicago house legend Paul Johnson. Glasgow’s status as an electronic music hotbed is well established, but the reputation it now enjoys has a lot to do with what was going on eight miles southwest of the city in the mid 1990s. During this time, the town of Paisley became an unlikely outpost for some of Scotland’s most exciting and out-there electronic music. Through its ties to Rubadub, which first sold records in a backstreet in Paisley, Club 69 was a home for some of the fiercest Detroit techno and electro around, while also hosting DJs of the caliber of Chez Damier, Erik & Fiedel, and Matthew Herbert.

“People would travel from Edinburgh [to Rubadub]; visiting DJs would make the journey out to the ghetto to come and buy some records,” McKay says. “I still stay in Paisley. That’s my wee stomping ground. It’s good that people would come from Glasgow for a good night out. It’s not so much like that in this day and age; Glasgow, over the years, has become a hive of good musical activity. There’s umpteen things on every night in Glasgow these days. But you pretty much had to go to Paisley if you wanted something a bit different.”

McKay’s outlook pervades everything that the shop does, and that’s especially true of the shop’s selection of records. There’s a distinctive strain of house and techno throughout a lot of the shop that one would expect to find (from Clone’s party-starting, Chicago-indebted Jack For Daze series to more soulful fare from Wild Oats and Sound Signature alongside a newly installed section of UK dance music hybrids like Swamp81 and Livity Sound), but what sets the shop apart is its range of experimental electronic music, which reflects McKay’s insistence that Rubadub is as much a shop for music lovers as it is for DJs. Flipping through its racks, one might come across Kerridge’s A Fallen Empire, a soup of industrial noise and a study in isolation; the thoroughly strange circus dread of The Maghreban’s Afric EP; or the coal-smeared techno sketches of Bronze Teeth. That these records sit alongside more straightforward DJ tools, as opposed to having their own “experimental/leftfield” section, says something about the “unhinged, unrestricted” outlook of Glasgow’s music scene as a whole, as Lurinsky puts it.

“Electronic sort of records were very big for us years ago,” McKay adds. “There weren’t that many people that did them, but they were our biggest sellers. You could sell more weird electronic stuff than straight-up house and techno. In more recent years, it’s not been such an easy sell, but I think it’s just been people that are into the musical vibe of Glasgow [that buy them].”

McKay and Lurinsky look at things in retrospect a lot, and that’s inevitable for a shop that’s run for so long. Over and above all the upheavals independent record stores have faced since the 1990s, the biggest change of all has been the customer. McKay describes 1998 as the heyday (he’s referring to Rubadub, but he could be talking about independent record shops in general): queues of people at their Virginia Galleries store (one of four premises Rubadub has occupied), with inch-thick piles of records under their arms picked up on the recommendation of one of Rubadub’s staffers. The internet, McKay says, has since removed some of this curatorial authority from record stores.

“It used to be you had a bigger control of the creation of the musical [journey], the stuff people were listening to, because people were trusting the judgement of the person in the record shop. Maybe that’s still the case to an extent, but there’s the internet now and people are listening to stuff before they come in. They know about things before they come in. It used to be me in the shop, for example, that would have the knowledge of things coming out to impart to your customers. Customers are now imparting the knowledge onto me sometimes!”

“Everyone’s an expert these days,” says Lurinsky. “But yeah, it’s definitely a new thing, that.”

Does this mean that customers who know what they want also come in with a “I know best” attitude? That’s still the exception rather than the rule, Lurinsky says.

“People still come in and ask for recommendations. We still get a lot of customers who have never come into the shop, especially at this time of year, students and younger folk who move to Glasgow. There are customers who have come in for years who still do that; you give them a wee pile, and once you build up a relationship with them, you know what they’re into anyway, so you don’t need to just keep flinging random things at them.”

“I’m sure some people still appreciate that sort of service,” says McKay.

“And then you get people who tell you your selection’s shite,” adds Lurinsky.

Even if that was the case—and 22 years of trading suggests that it isn’t—it would be difficult to say the same for Rubadub in general. Though the shop puts on parties less often now, the last few years have nonetheless seen Rubadub playing host to top-drawer acts like Jeff Mills and Virgo Four. In fairness, Rubadub’s distribution business is a significant part of the enterprise too, but McKay, as he tends to do, plays that down, and echoes the convictions of his youth when he says he sees rival record stores as his customers as well as his competition.

“I know what these guys are like, what they’re going through,” he says. “[Certain stores] are doing it for the same reasons as ourselves, and I want to help them still survive and keep their livelihood going. I’m not gonna go in there and try to be competitive like a supermarket, you know what I mean?”

At this point, Lurinsky begins to describe the shop as an approachable place with a friendly atmosphere. Granted, this is something of an off-the-shelf self-appraisal from anyone who runs an independent business, but Rubadub’s physical space—or lack thereof—makes the alternative impossible. The store sits in a 10m x 7m area, and it’s rammed to the gunnels with vinyl racks, equipment, cardboard boxes, and, most importantly, people. There’s no hiding place. Glasgow’s electronic music scene is like this too. It’s a small community in a city that, sometimes, feels even smaller, but it also punches above its weight for pretty old-fashioned reasons: passion, hard work, and solidarity. When combined with a native instinct to rebel against the established order (or, if we’re using the local lingo, to take the piss), then it’s easy to see why Rubadub continues to serve Glasgow, and many other places, so well.