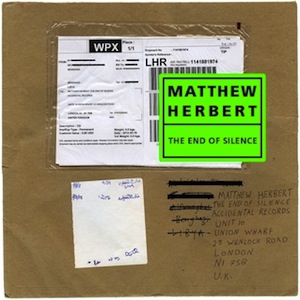

Matthew Herbert The End of Silence

The newest record from Matthew Herbert is about as far from the dancefloor as his […]

The newest record from Matthew Herbert is about as far from the dancefloor as his music has ever been, both in terms of source material and the end product. This time, the restlessly inventive UK musician draws directly from the middle of an actual wartime situation in Libya. Although the subject matter and the source material is heavy and frightening, Herbert and his collaborators handle it deftly, forging a freeform-yet-gripping path into a loaded snippet of sound.

Like Herbert’s recent One trilogy, the production of The End of Silence involved a restraint on the way in which it was recorded. Specifically, all of the instrumentation on the album was created using a 10-second audio recording made in Libya by war photographer Sebastian Meyer on March 11, 2011 during the battle of Ras Lanuf. The sound is of a pro-Gaddafi plane dropping a bomb, apparently somewhere near Meyer. In this clip, a plane is heard approaching, someone whistles as if to warn people nearby, and then a jarring, ear-splitting explosion occurs.

What’s done with this sound is not really collage, per se. Although credited to “Matthew Herbert,” the album is actually the work of a four-piece group of musicians playing special sample instruments created using manipulations of this short clip. Jamming together and recording in a barn over three days, the outfit ultimately came up with this nearly hour-long piece. Although the conceptual focus is on the specific sound clip, the album’s recording location did introduce happenstance ambient sounds that would have otherwise gone unexplained, such as birds chattering and dogs barking.

The first of the album’s three parts begins with the 10-second clip before quietly, ominously humming and creaking for several minutes with a cold, tinny tension. Sixteen minutes into this 24-minute track, the explosion vividly spikes through, signaling a brief, squalling escalation of the track’s scratchy whirr before the component parts unwind in a disoriented exhalation that introduces the grinding, glitched rhythms of “Part 2,” the most composed-feeling part of the record. It’s too disquieting to be catchy, but the passage sets its hooks in nonetheless. Much later on, in “Part 3,” what sounds like a sped-up clip of the explosion turns into a drum, stamping at a marching pace before fanning out into a gurgling, dizzy-feeling finale.

This record is difficult to separate from its context, but on a purely musical level, it most certainly packs a resonant wallop. There are some detectable recurring bits from the source recording that make it fairly clear where this record came from: the bomb’s detonation, the fearsome whirr of the plane flying overhead, alarmed human chatter. Still, even without a complete explanation, the music can easily be heard and appreciated as the abstract, tense piece that it is.

As the title of The End of Silence suggests, what Meyer experienced (and, by proximity, Herbert experienced and the listener experiences) is a moment so intense that it cannot be easily unseen or unheard. The record provides a vivid, gnarled exploration of the immediate horror of this moment, and moreover, that of war—a less-than-cool topic that’s frequently glossed over in the media and is likely something that many of Herbert’s listeners haven’t experienced firsthand. In the end, his attempt to tackle the alienating, intense feelings related to this subject turns out to not only be insightful and emotional, but oddly graceful as well.