Record Store Week: Juno, Bleep, and the Challenges of Digital

In advance of this Saturday’s Record Store Day happenings around the globe, XLR8R has put […]

Record Store Week: Juno, Bleep, and the Challenges of Digital

In advance of this Saturday’s Record Store Day happenings around the globe, XLR8R has put […]

In advance of this Saturday’s Record Store Day happenings around the globe, XLR8R has put together a week-long series of features devoted to taking a closer look at some of our favorite record-selling outlets from around the world. Check out the entire series here.

It virtually goes without saying that the internet has changed music—without exaggeration, it’s a fair assertion that the past two decades have seen the entire concept of music consumption completely deconstructed and rearranged. On the downside, illegal downloading has crippled record sales and music has, for many, lost its value entirely. Where fans once hunted down releases and cherished their collections, music has now largely been transformed into something to be downloaded en masse and allowed to sit unlistened on some forgotten hard drive.

Yet the shift to online has altered dance music in a more personal and specific way. Speak to any DJ or dance-music fan over the age of 30 and they’ll likely recall a very similar account of their first experiences buying dance music. It’ll almost surely involve a pilgrimage to some small record store in their nearest city, where they’d stand by listening decks to hear stacks 12″s recommended by staff members, or perhaps dig through badly organized crates to seek out rarities that simply weren’t available any other way. These specialist stores acted as hubs for DJs and in many cases give birth to genres themselves; it’s impossible to discuss a history of dubstep, for instance, without mentioning Big Apple Records—the small South London store that counted Skream and Hatcha amongst its employees. And while these meticulously curated, specialized stores still exist the world over, they are no longer the necessary entry points into the dance-music community they once were. These days, it’s easier and often cheaper to buy music—be it vinyl or download—online, and there’s no reason that one can’t become a dance-music aficionado or accomplished DJ without ever setting foot in an actual real-world record store.

While it’s easy to be down on this idea, the situation is not all doom and gloom. Sure, faceless behemoths like iTunes and Amazon might dominate the download market, and Beatport might remain the number-one place to grab EDM bangers and celebrity DJ charts, but there are sites that fully embrace the historically personal ethos of underground dance music.

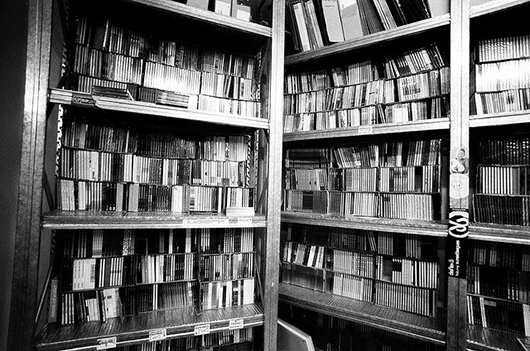

Richard Atherton, Juno Records

UK-based store Juno Records is an example of one such establishment. Since launching online in 1996—originally as a dance-music information resource, although it quickly expanded into commercial endeavors—Juno has done a fine job of acting as a relatable face amongst the anonymized world of online retail. The nearly two decades since the site’s launch have seen Juno branch out beyond its original vinyl and CD remit into downloads—via the Juno Download sub-brand—along with DJ gear and accessories. Where the site seems to differ from countless rivals that have fallen by the digital wayside, however, is that despite all the necessary diversification, it has managed to maintain an air of specialism and genuine interest in the products it sells.

“It’s not much of a challenge being specialist online; online is great for specialism,” Juno co-founder Richard Atherton explains. “One difference between us and a traditional record store is that, although we’re mainly focused on house and techno, we’ll also sell things like drum & bass, hip-hop, and rock in the same store. So what we share with those [pre-internet] specialist stores is that we can care a lot about the individual products and know a lot about the individual records we sell, but we’re able to try and be very diverse with that as well.”

Juno Records

For all the benefits that the reach of being online brings, however, it obviously presents challenges for any record store trying to connect with a specific music scene or fan base. Stripped of the geographical roots, history, and face-to-face interaction that contributes to the legacy of any iconic record store, digital retailers are faced with a natural divide between themselves and music fans.

Dan Minchom, General Manager of independent-music specialists Bleep, picks up on this theme. “We try all the time to take things from the traditional record store experience,” he says. “We are not trying to recreate it, but when we look at the way we work, it’s very clear that the biggest disadvantage of shopping online is the barrier between our team and the shoppers and the way that a traditional record store creates a community around it. Trying to reduce this barrier is really important to us.”

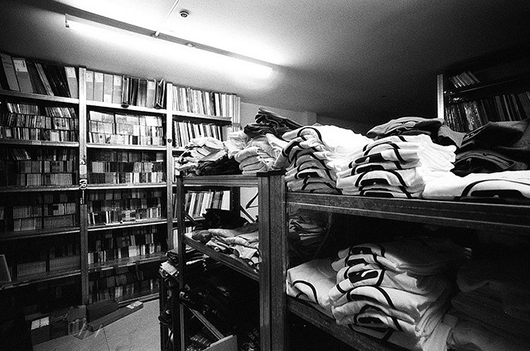

Interestingly, Bleep entered the digital market from a completely different perspective than Juno. Whereas the later cut its teeth selling physical music, when Bleep launched in 2004—as a sub-division of iconic British electronic label Warp—it was originally a digital download-only store. It was only in 2008, when the site merged with Warp’s physical record store, WarpMart, that the site moved into selling CDs and vinyl. Both Juno and Bleep have come to provide similar services and connect with similar groups of music fans, however, with each specializing in independent, electronic-leaning music that seems to be bound by its ethos more than specific tempos or genre traits. It seems there can be difficulties in this sort of loosely specified specialism though.

Bleep

“There are many challenges,” Minchom explains. “The hard one is explaining and defining what we sell to the rest of the world. Our team knows what music Bleep should be selling and it’s not specific to one genre, style, or era. Essentially, we sell what we consider to be good music, but the world likes to categorize in genres.”

As the internet’s grip on dance music has tightened over the past decade, it seems these challenges brought on by the blurring of genre boundaries and melding of specialist scenes have only intensified. Yet alongside the difficulties brought on by communicating with a global mass of ill-defined micro-scenes, interesting trends have emerged—not just across genres, but across formats too.

Atherton explains, “When we started in the ’90s, as we always have, we sold all sorts of different kinds of music—you still had hardcore and rave sitting alongside IDM, as it was then—but it was all united by vinyl, and that wasn’t something we really noticed at the time. But when downloads came along, it sort of cracked the market into two, so certain genres and types of DJ went one way, and other DJs went another way.” He explains that sales of dance music in the US have moved towards more commercial, crossover territory—incorporating big chart names and focusing on track downloads—while in Europe, electronic music has increasingly sunk underground. “In a strange way, we’ve kind of become more of an underground store since the mid ’90s,” Atherton says before concluding, “We’ve grown as a company, but at the same time, we seem to be catering to a more fractured and diverse set of audiences.”

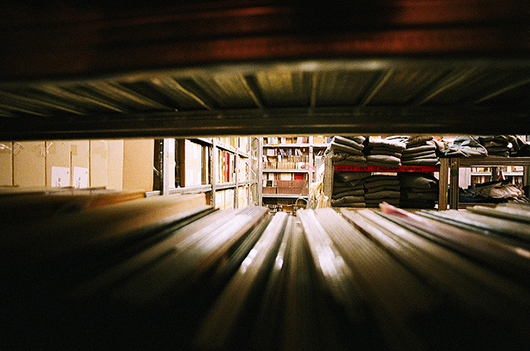

Minchom identifies similar shifts in demand since Bleep’s inception. “Digitally, there has been a move to higher-quality files and more bundling of digital with physical music,” he explains. “On the physical side, the changes have been even greater. CDs are becoming obsolete, but still sell significant quantities if packaged nicely. Vinyl sales have been increasing in recent years, but this is not across the board. Dance 12″s are now selling very little compared to a few years ago, whereas vinyl albums are booming again.”

Juno Records

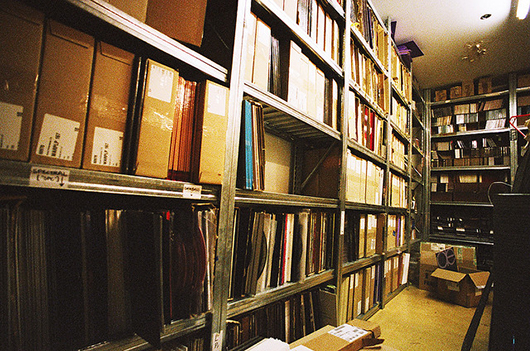

If there’s one thing that appears to link the more likeable and, it seems, more successful digital record stores out there, it’s that each has developed some form of personality by branching out into editorial and critical endeavors. Manchester-based outlet Boomkat, for example, has become recognizable for the highly personal tone of the reviews it supplies under each record listed on its site. Both Juno and Bleep have developed strong editorial presences as well; the former through its Juno Plus outlet, which supplies a constant feed of features, news, and record reviews, whilst—along with a host of blogs, charts, and features—Bleep has made a name for itself with its excellent podcast series, which sees the site regularly collaborating with the likes of NTS Radio and Sonic Router.

“They are essential,” Minchom explains of Bleep’s editorial outlets. “They are our voice. It is our way of talking to our customers and expressing who we are.” Atherton echoes this sentiment: “I think, in terms of the internet and retail, the first wave was—and I still think this is the case with Amazon and things like that—quite an impersonal experience.” He continues, “It was sort of just this online service where records were moved from A to B. I don’t think people are so satisfied with that anymore; as internet shopping has become more sophisticated, people want stores to have more of an identity and knowledge. It’s not necessarily about dictating things, but they want the stores to prove their credibility or their caliber, and [demonstrate] that they know what they’re selling.”

Bleep

In a way, this doesn’t seem a million miles away from the manner in which real-world record stores have operated for years. Pulling in the right sort of customers and proving one’s credentials with broadcasts, features, and editorial is just a logical extension of the record-store employee hanging out at the counter, recommending new releases, and discussing tunes—albeit on a grander, and perhaps less interactive scale.

“That was quite a natural thing for us, as we already had quite a lot of DJs and writers working here,” Atherton continues. “We’re not interested in preaching to people and telling them what to buy, but rather facilitating the music buying of people who already know their music.”

Ultimately, it still seems unlikely, to say the least, that record stores in the digital age could ever become the iconic birthplaces of genres that some of dance music’s most famous outlets are seen as. Looking back over some of the locations featured on XLR8R over the past week, it’s hard to imagine a website could ever take on the same sort of mythology and legacy. But they can still work their way into dance-music culture—Joy Orbison’s “Big Room Tech House DJ Tool – Tip!” for example, is named as a playful reference to the track-labelling conventions of esteemed German shop Hardwax. Crucially, however, it seems that specialist stores in the digital age can certainly be lovingly curated, and don’t have to feel impersonal. In fact, at their best, they can open up underground dance music to the world on a level that was once completely unimaginable.