By the Power of Dre Skull

On any given day, you might find Dre Skull (a.k.a. Andrew Hershey) flying to London […]

By the Power of Dre Skull

On any given day, you might find Dre Skull (a.k.a. Andrew Hershey) flying to London […]

On any given day, you might find Dre Skull (a.k.a. Andrew Hershey) flying to London to DJ at Notting Hill Carnival, recording with Lil Scrappy in Atlanta, working with an 18-year-old R&B vocalist he met on Craigslist, or hanging out with bounce rapper Katey Red in New Orleans. You might find him in Williamsburg grabbing a vegan pizza slice and a green juice. Then again, you might not be able find him at all. Despite his distinctive look—Wayfarers, loose-fitting clothes, and a dark, wiseman-style beard that makes him look something like a skinny Rick Rubin—the Brooklyn-based DJ/producer/Mixpak Records boss remains an elusive figure, the skull nodding in the back of the dance rather than the head in all the party photos. He’s equally to hard to pin down musically, but it’s precisely this fluidity that has allowed him to move between producing anthemic ’90s dance cuts for Midwestern indie rapper Juiceboxxx, working with rappers Pusha T and Lil’ Scrappy, and creating reggae riddims voiced by the likes of Sizzla and Beenie Man.

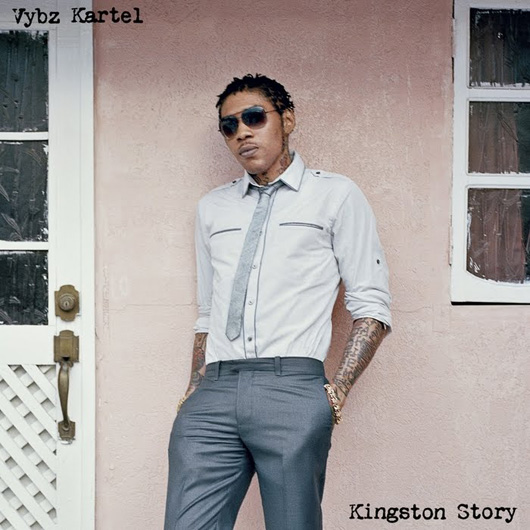

The last year of Dre Skull’s life has been the most compelling part of the tale yet. In June 2011, he wowed everyone by releasing an entire record with bad-boy dancehall star Vybz Kartel on (The album, Kingston Story, was recently re-released as a joint venture between Mixpak and Vice Records.) Several months later, he got a text from Diplo asking him to fly to Jamaica with Major Lazer to work on Snoop Dogg’s forthcoming record. Snoop had no intention of making another rap album—he wanted to make an LP inspired by Jamaican music and would eventually reincarnate himself under the reggae alias Snoop Lion. Meanwhile, videos from Kingston Story were racking up over seven million YouTube views and, amidst wild rumors, Vybz and members of his Gaza camp were incarcerated in Jamaica on murder charges. Somehow, Dre Skull sat in the middle of all this, prompting the question: how did an ultra-humble art-school dude from suburban Massachusetts go from performing at Deitch Gallery on a trampoline to being one of urban music’s rising production stars?

“I’m so curious about pop songs–they kind of have a hold on me or the idea of figuring out how to make them,” explains Dre. (Full disclosure: This isn’t our first meeting—I’ve worked with Dre Skull on music projects in the past and he is a former roommate of mine.) “Maybe I’ve chosen that as the goal because it making pop seems like the hardest thing to me. I’ve never felt like I’ve had a natural aptitude toward music, but somehow, that’s what’s made it interesting; I take a bit of an analytical approach to finding out what goes into making the songs that I like.”

Listening to a few raw instrumentals Dre Skull made for Snoop, it’s hard to believe he ever didn’t know how to write a pop song. These are wonderfully constructed and catchy skeletons, anchored by soaring and melancholy choruses contributed by top-liners such as Jahdan Blakkamoore and Angela Hunte (who wrote the hook of Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind” and has dubbed Dre “The Prime Minister”). Long hours of studying everything—from chord books to Hot 97 to The KLF’s manual on how to have a number-one hit—seem to have paid off.

Dre composed about 17 or so tracks before he met up with the Major Lazer team (Diplo and production partner Ariel Reichstad) to work with Snoop, but that didn’t stop the recording process from being intense. While the trailer for a forthcoming documentary on the project (being issued by Vice) shows Snoop partying, smoking, and being blessed by Bunny Wailer, the producers look kind of stressed. “The production team was doing something like 18-hour days for two-and-a-half weeks straight, with only about one full day off near the end,” recalls Dre. “We’d often hear that Dogg was ready to record, but then we inevitably might not see him for a bit. After a while, we’d see him on Twitter saying he was Ustreaming live in Jamaica. So we would pull up the Ustream of Snoop—who was on camera listening to reggae, smoking a blunt, drinking Red Stripes, and talking to his audience—and we’d use that as a way to gauge when the recording would start. The whole time he was on a porch just below the studio, about 75 feet away.”

“Overall, though, the process was incredibly smooth and the album came together just so,” says Dre. “Snoop was super cool. It felt like meeting the Snoop I’ve grown up listening to—he is that person, it doesn’t fall away when he’s hanging out. And he’s really all about music. The first day at Tuff Gong when Snoop was listening to tracks for the first time, just seeing him knocking his head to tracks of mine was special.”

It’s songs by the likes of Snoop, Supercat, and TLC that originally diverted Dre away from the art-punk scene that defined his teen and early college years, though that background had a profound influence on everything that came later. “I wasn’t ever a kid only riding for one type of music… sort of how I am now I guess. We would listen to Fugazi and The Pixies, and rap was definitely an early love: Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys, among others. Then I got into Lee Scratch Perry—reading about him and the idea of a producer as an important piece of the puzzle was pretty influential. Maybe because I wasn’t a particularly good musician, that got me excited. He was kind of a wild guy. He would record an amazing song on two-inch tape, then dig a hole in his backyard and bury the tape for a few weeks; then he would dig it up and play it and be like, ‘Yeahhh. Now it sounds good.’ Literally, he would say stuff like, ‘It’s got to get some of that earth in the sound.’ At that time, I was interested in the recording process and I was messing around with a four-track and delay pedals, and he was the guy that took that to the furthest point that I had heard about.”

Dre Skull eventually began spending summers with a childhood friend in Providence, Rhode Island, home to famed art school RISD. It was the heyday of warehouse jam sessions and wild freakouts involving the Fort Thunder collective, which birthed visual artists Jim Drain and Ara Peterson, as well as the noise-rock duo Lightning Bolt (who Dre once toured with selling merch). “DIY wasn’t some great thing I worshipped, but it was an empowering thing to see that you can put out records, you can tour, and you can put out merch just because you say you’re going to do it,” he recalls. “You don’t really need any permission or you don’t have to send your demo out and hope that someone responds. All you need to do something is to decide you want to do it and then figure out how to navigate it.”

Through Providence connects, he would eventually move into a four-story warehouse in Brooklyn with a bunch of artist friends and start developing the ideas that would ultimately lead to Dre Skull and Mixpak Records. At first, though, he was in a series of conceptual performance art “bands,” with names like Farcefield and Slow Jams and the Bobby Brown. The latter was a hip-hop-and-sampling-influenced art disaster that one reviewer called “an unwieldy mixed media circus somewhere between Fluxus performance and MTV’s Jackass.” “It basically performance art,” he remembers. “For instance, we reworked a Yoko Ono piece where she and this guy had sex in a bag; we would go inside a bag as this threesome and then on a video screen there would be footage from inside the bag as if the footage was live. After a while, we got kind of obsessed with technical failures. As a performance-art group, we were relying on pre-recorded videos and musical elements—one DVD skip and you’re over. So we started playing with those audience expectations of failure or what a band does. What we were doing—not in terms of our performances, but where our minds were—was deconstructing popular culture. After a while, I started thinking that I’d rather construct culture from the ground up than deconstruct culture that other people had made. I wanted to see if I could actually craft a popular song.”

Even with the “success” of such projects—they performed shows at Deitch Projects, PS1, and MoMA—Dre was nursing serious urban dreams… and luckily, he’s kept most of his old production sketches on the seven or so hard drives that populate his studio. “There are songs that I made in [that] era that ended up on the Kartel record,” he says, laughing. “I guess I had enough insane faith back then that these tracks were good enough to hold back or put in a stash. I was thinking, ‘This would be a good track for Rihanna,’ or whoever, but at the same time, I had no idea how to go about getting it to them. In the end, I did meet with some major label A&Rs and bring them tracks. In some ways, [just getting those meetings] gave me the hope to continue.”

Of course, producing an entire Vybz Kartel record didn’t exactly materialize out of thin air. The road to Kingston Story began in 2008, before Mixpak Records had even been born. “Initially, I was interested in working with a Jamaican vocalist and using the internet, I figured out how to do that,” says Dre. “You can find the wildest shit on the internet! For example, a collection of every major-label A&R’s email that someone copied and pasted in some weird website that has now been retained by Google. I found a go-between person, and talked with them about [what dancehall vocalists in Jamaica] I could get to. I ended up making a track for Sizzla; we did it strictly over the internet, like a dubplate-session style.”

The track, “Gone Too Far,” launched Mixpak Records in March 2009, surprising many who knew Dre Skull from his electro remixes and the trio of ravey hip-house jams he released with longtime friend Juiceboxxx, a Wisconsin indie rapper. Though the bpms were changing, a fledgling Dre Skull sound had already begun to emerge: shimmering trance synths, one-two brass-band stomps, and catchy chord progressions. These uplifting sounds would eventually form the backbone of bonafide Skull hits like Popcaan’s “Get Gyal Easy” and Vybz Kartel’s “Go Go Wine.”

Shortly after “Gone Too Far,” Dre sent a 120-bpm beat (eventually released as “Loudspeaker Riddim”) to Vybz Kartel’s camp in Jamaica, hoping to get it voiced. Then he waited… and waited. In the meantime, he released a weird house record (“I Want You”) and a flagrantly explicit track by sissy-bounce rapper Sissy Nobby, whom he discovered in New Orleans. Then, he waited some more.

After months of being told that Vybz was writing to the track, a message came through that he wasn’t going to submit anything. Frustrated, Dre pondered his next move. “I already had the instrumental for ‘Yuh Love’ on my computer,” he says. “It wasn’t exactly what I wanted to do with him, but it had already been three or four months. I sent it and within 48 hours I had an email that said, ‘Mad tune! Sell off.’ It was a strange roll of the dice. I didn’t want to put it out for a few months, but they leaked it to YouTube literally that day. So I mixed it, got the cover art, and put it out within 10 days with no promo or anything, and it has had an amazing life over the last few years.”

“Even though I was already dreaming about producing big records in the US, I don’t think it was in my imagination that I would be making records with people in Jamaica,” he continues. “The success of ‘Yuh Love’ got me feeling like I could do that.” Dre’s initial plan for his first trip to Jamaica was to work on three tracks—one each with Vybz Kartel, Busy Signal, and Elephant Man. This idea was squashed as soon as he landed by a business email from VP Records, who refused to let him put out any singles with their artists and wanted right of refusal for any track he worked on with Busy Signal or Elephant Man. So Dre called up Kartel and they ended up making three songs in one night. “He loved my production and he said, ‘Yo, we just made a mini-album.’ Something about him using the word ‘album’ made me think… So I took those tracks, figured out the deal, and started to go back to Jamaica every few months.”

Despite having access to the best studios in Jamaica, most of Kingston Story was made where Kartel felt comfortable—with his (now estranged) engineer Notnice at a bedroom studio in a heavily-gated apartment complex in Kingston. “I personally had never come across someone who had that kind of talent,” Dre says of Kartel. “He would sit down in a chair, turn the lights off in the room, and have a microphone recording. From the first time he hears the song, he starts making guttural sounds, just searching for a melody. Within 10 minutes, he’d start putting down the final takes on vocals, not writing down anything. Except for the very last time we recorded together, every time he’d be done with a whole song in an hour and a half, sometimes 45 minutes. On the craziest one, he did an entire 12-bar verse backwards: bar 12 first, then bar 11, bar 10.”

The music and vibes came easy—getting Kartel to show up did not. “Kartel would basically say ‘Let’s work tonight 8 p.m.’ and cancel every night… at 8 p.m. I couldn’t do other sessions with other artists, or anything really. From 8 p.m. to 2 a.m., I was constantly being told another hour.” When it came time for Kartel to sign the record deal, it got extra crazy. “Kartel knew I was scheduled to leave Jamaica the next day and I was hoping not to leave without the contract. He told me to come to the studio and when I got there, I was locked out and he wasn’t there. He kept telling me he was 10 minutes away from meeting me (for five hours) and I waited on the dead end of this sketchy street until five in the morning. I was sitting in the front seat of a car and I had all this cash stashed under the seat. I was probably making the neighbors nervous, and it also felt like I was going to get jacked. Crazy shit would go down, like a black Beemer with fully tinted windows pulling up, putting their headlights on my car on the perpendicular and just sitting there for a few minutes. But I wasn’t going to leave. In retrospect, maybe Kartel wanted to give me a test of some kind before he signed, or he might have very well been partying with a lady at Street Vybz Thursdays. Who knows?”

Even with the hoops he occasionally has to jump through, Dre takes a pretty equanimous approach to things—despite his menacing-sounding name, he is a chill dude. “If you go outside your own front door to work on music, you got to drop a couple preconceptions, or be willing to understand how things get done (or don’t get done). Or at the very least have some patience and not feel entitled to quick responses or easygoing endeavors or deals.” This has often meant taking a zen approach, and letting some projects fall by the wayside, like working with Diamond from Crime Mob or finishing a New Orleans bounce documentary he started with a photographer friend.

While Dre Skull searches for his perfect pop moment overground, he’s got plenty bubbling up in the underground. He also has some rather cutting-edge (albeit secret) plans for his Mixpak Records label, an eclectic roster that includes rising dancehall star Popcaan, tropical bass stormers Poirier and Dubbel Dutch, and even a Japanese all-girl punk group called Hard Nips. Though Mixpak is best known for its tropical vibes and hand-drawn aesthetic, it remains an impossible label to categorize sonically, with ingenue Andy Petr turning in experimental future garage, Jubilee trafficking in Miami bass-inspired sounds, and a new compilation series (Mixpak Pressure) kicking off with a series of trap instrumentals.

“My take on a modern music listener is that they’re open to listening to a lot of different music,” says Dre, explaining the label’s ethos. “Throughout the day, they’ll listen to a dancehall mix, a deep-house mix, Pandora, and all these other things. It’s like what Afrika Bambaataa was doing—if he liked it and he felt like it would get the club rocking, he would drop it. Whether that’s a good business model, I don’t know. It’s definitely more complicated. But for me to do a narrowly focused label feels like a fraud. I would feel like I was selling my interests and my passions short. I feel, in a way, that I’ve chosen a harder battle, but I don’t think I could have chosen another way.”

Like a zen master, Dre breathes deep, takes a swig of green tea, and contemplates his future. “The best advice I ever got basically said: ‘If you endeavor to do something well, after three years of working on it, you might not realize you have improved all that much. After 10 years, you might realize you are finally getting better, but after 20 years, you will realize you are a changed person.’ It’s a story about patience and dedication that I take to heart.”