2010—2020: The Moments That Defined the Decade in Electronic Music

Recapping 10 years that gave us EDM, post-ironic parodies, and cancel culture, as well as a handful of half-decent tunes.

2010—2020: The Moments That Defined the Decade in Electronic Music

Recapping 10 years that gave us EDM, post-ironic parodies, and cancel culture, as well as a handful of half-decent tunes.

A little over a decade ago, The xx, a guitar band who had recently appeared on Jools Holland alongside The Cribs and Shakira, gave an interview to NME talking effusively about their love for dubstep. James Blake, a 21-year-old pianist, had just released his first EP and would soon become the poster boy for the post-dubstep sound. His American counterpart, an aspiring producer called Skrillex, was working on his own supersized dubstep interpretations.

All acolytes of London’s mid-’00s dubstep scene, these three acts stood at pop’s frontier at the decade’s end. The xx suggested a new model for the guitar band where drummers were replaced with computer-minded beatmakers. Blake was the prototype for the next generation of singer-songwriter. After 10 years dominated by indie rock, it seemed like the future might be electronic.

Most significant of all was Skrillex, whose music laid the foundation for a genre soon to be known as EDM. To some, the term still simply means electronic dance music, an umbrella grouping together techno, house, drum & bass, and the rest, but whatever your definition, EDM’s explosion was the first time electronic music has truly conquered the States, and, therefore, the world. It’s responsible for some of the era’s most unavoidable hits and has bred a new class of millionaire DJ. And though EDM blazed the trail, house and techno have ballooned in popularity this decade, too, with the biggest names now commanding six-figure fees for some gigs and festivals.

While pop acts have taken inspiration from electronic music for decades, this has been the first era in which electronic artists could themselves be considered pop stars. The promise of fame and money means aspiring musicians now want to be DJs as much as guitarists or singers. While some have clung to a stubborn belief in the underground, other electronic artists have used the mainstream for inspiration, producing commentaries on capitalism and commercialism through humorous, sometimes satirical takes on pop.

Remembering the decade in which electronic music went global, here is a timeline of the events that got us where we are today.

“nobody here” is Uploaded to YouTube (July 19, 2009)

“What a bunch of stupid bullshit this has all become,” said Minesweeper2000, a user commenting on the Discogs page for 2010 album Eccojams. Currently selling as a cassette tape for £1,540, Eccojams was made by Daniel Lopatin (a.k.a Oneohtrix Point Never). The album features “nobody here,” a two-minute track featuring a sample from Chris de Burgh’s 1986 ballad “The Lady in Red.” When Lopatin uploaded it to his YouTube channel, sunsetcorp, in 2009, it inadvertently started the internet micro-genre soon to be known as vaporwave, a hazy, chopped form of ambient music that placed slow-mo loops of ’80s pop songs together with emotional clips of The Simpsons.

Over the ensuing decade, vaporwave came and went, but its aesthetic (or a e s t h e t i c, as spaced-out fans styled it) said more about the era than perhaps any other genre. The ethical use of other people’s music—which vaporwave placed in stark reality through samples of anything from Marvin Gaye to shopping mall soundtracks—became an era-defining debate, in which classic albums were reappraised, the authenticity of emergent scenes was undermined, and the very practice of DJing was questioned.

“I’m uncomfortable with the idea that I’m an author of this stuff,” Lopatin was quoted as saying in Simon Reynolds’ “Retromania,” a book about 21st-century music’s addiction to repeating ideas from the past. As though tailor-made to suit Reynolds’s theory, vaporwave obliterated the linearity of history, placing temporally disparate moments absurdly side by side: take the album cover of Macintosh Plus’ genre touchstone Floral Shoppe, which depicts a Roman bust alongside a VHS image of New York. The music, meanwhile, centres on a skittish, scatterbrain tendency to flick between unmatching sounds, mirroring the attention span of a dazed millennial as they scroll through Twitter.

On JOECHILLWORLD, another proto-vaporwave record, rapper Devon Hendryx (now known as Jpegmafia) spits: “Rap my ass off and still have nothing to show for it / Gain a cult following, the pits of passion / Never clear my samples, get sued by Janet Jackson.” Such is the plight of an artist in the 2010s: bemoaning music’s measly financial return while using someone else’s work without giving them credit, albeit with the same post-ironic tone that now pulsates through online chat rooms, electronic music discourse, and indeed most of modern culture.

PC Music Launches on Soundcloud (June 23, 2013)

A. G. Cook’s internet record label PC Music went beyond even vaporwave in its embrace of technology and artificiality. When it began life by publishing GFOTY’s Bobby and a slew of subsequent releases to Soundcloud, the music world recoiled. Artists like GFOTY, easyFun, Hannah Diamond, and Princess Bambi seemed to come from a world where houses were made of sugar, where everyone smiled until their cheeks hurt, and where 3 of a Kind’s “Babycakes” was the most influential song ever made. Terms like “post-ringtone” and “bubblegum” became commonplace in describing the label. Fact’s Alex Macpherson called it “pure, contemptuous parody.”

In its hyper-digital, maximalist bombast, PC Music was everything you could want in a new sound, the like of which Simon Reynolds had argued was so dearly missing in contemporary pop. Its success and influence centre on the meteoric rise of SOPHIE, the Glaswegian producer and singer who started out producing tunes like QT’s “Hey QT” alongside PC boss Cook before later working with Charli XCX, Vince Staples, Lady Gaga, and Madonna. Like many a PC artist, SOPHIE’s music questions the very media through which it is transmitted, addressing through songs like “Faceshopping” and “Immaterial” the synthetic and superficial world in which we live. Her debut album, Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides, is as defining a document of the zeitgeist as anything made this decade.

Grimes Plays Boiler Room (August 14, 2013)

As Resident Advisor’s Will Lynch recently pointed out, 2019 was the year of “business techno”—a term used variously by Reddit users, jealous producers, post-ironic commentators, and Drumcode customers to define a lucrative, identikit brand of 4/4. On global festival stages and in BBC documentaries, serious, straightforward techno has never been further from the underground. And with it has developed an insidious new clubland archetype: the techno purist, who listens to nothing but techno and condemns any deviation from the genre in the sets of his—and it is usually a him—favourite DJ. Thankfully, there has been a reaction, brought into the light by Grimes and her infamous Boiler Room DJ set in 2013.

This set had everything: a middle finger to the status quo; misogynistic remarks in the comments section; bangers upon bangers upon bangers. They weren’t typical 2013 Boiler Room bangers though, but rather Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas,” Daddy Yankee’s “Gasolina,” and the Venga Boys’ “We Like to Party.” Back then, playing cheesy pop songs in a serious mix series was so controversial that Boiler Room refused to even publish the set—and they still do, except in snippets.

As though modelled precisely on opposing the techno purists, a silly style of DJing has recently risen to prominence and it now makes Grimes’ Boiler Room seem pretty normal. That’s not to say they’re not skilled operators—far from it: spinners like Ross From Friends, Mama Snake, and DJ Bus Replacement Service have navigated between supposedly uncool sounds like gabber, heavy metal, and the most egregious of pop tunes with unerring ability in their sets.

Techno’s purity school remains strong though: Objekt was criticised for playing “bait EDM” after dropping SOPHIE’s “Immaterial” at Dekmantel in 2018, while Skee Mask was chastised on Twitter for not playing “only techno” at London’s FOLD in February this year.

Kelela’s Cut 4 Me Mixtape is Released (October 1, 2013)

When post-dubstep microgenre UK funky petered out towards the end of the 2000s, written off as little more than a novelty by various critics (to be fair, “Head, Shoulders, Kneez & Toez” was its biggest hit), some mourned its death as another British sound that had failed to reach its potential. But funky’s legacy lived on, kept alive by Kelela’s debut mixtape, Cut 4 Me, a transatlantic blend of R&B and rhythmically syncopated British bass music, released through London label Night Slugs.

Kelela used six different producers for the record, choosing between Brits (Bok Bok, Girl Unit, and Jam City) and Americans indebted to the British sounds of grime, funky, and dubstep (Kingdom, Morri$, Nguzunguzu). The pairing of Kelela’s smoky, magnetic voice with sparse club beats laid the foundation upon which singers like Mhysa and Erika de Casier would later build, while Cut 4 Me gave British bass a new lease of life. UK funky’s use of five snares in a bar—as heard on Kelela’s “Do It Again”—once made critics balk; such rhythms seem normal today, commonly deployed by producers like Sinjin Hawke, Murlo, Martyn Bootyspoon, and the many denizens of London’s hard drum scene.

DJ Rashad Dies (April 26, 2014)

No more exciting sound was brought to worldwide consciousness this decade than footwork. While some strains of electronic music lapsed into armchair listening, footwork—which had actually started in Chicago in the ‘90s—was named after a dance. Though proudly functional, whether on headphones or in the club, the genre’s 160bpm mangle of house, soul, funk, trap, and hip-hop can be achingly affecting, beautiful even. Never more so than the footwork made by DJ Rashad, a figurehead of the sound who died from a drug overdose less than a year after the release of his debut album.

His death might have threatened to end what had begun the decade as a struggling, little-known scene. Instead, the outpouring of grief from around the world showed that footwork had finally reached beyond Chicago and become a global concern, something Rashad had strived for his whole career. It’s easy to imagine how pleased he would be now, to see the sound he helped define taking on new, increasingly inventive shapes, as interpreted by artists like Jlin, Rian Treanor, and his old friends RP Boo and DJ Spinn.

Mumdance & Novelist’s “Take Time” Single Drops (June 4, 2014)

At the close of the 2000s, it seemed like grime might be a busted flush. Some of its forefathers—Wiley, Dizzee, Tinchy—had achieved superstardom, but only by sacrificing some of the sound’s edge in favour of poppy radio tracks like “Wearing My Rolex” and “Dance Wiv Me.” When Skepta and JME’s “That’s Not Me” reached Number 21 on the UK Singles Chart, it was a victory for grime’s old school: serious bars, pirate radio beats, and tracksuits (“I used to wear Gucci, threw it all in the bin cos that’s not me”).

Yet just as crucial was the new school that was bubbling up at the same time, rappers like the 17-year-old Novelist, whose track “Take Time” dropped two months after “That’s Not Me.” The instrumental, made by experimental producer Mumdance, was a kick drum pattern, a crashing snare, and not much else. It was icy, minimal, and crystallised “weightless” as a new style of grime production.

Weightless Volumes 1 & 2 soon followed on Mumdance’s label, Different Circles, while contemporaries like Logos, Raime, Mr. Mitch, Rabit, and Proc Fiskal took the sound in floaty new directions. Even further afield, as largely instrumental takes on grime have emerged from Uganda and Shanghai, “Take Time” has always felt like a touchstone.

Discwoman Founded (September 20, 2014)

Emma Burgess-Olson (a.k.a Umfang), Christine McCharen-Tran, and Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson started Discwoman in 2014 as a way of promoting “cis women, trans women, and genderqueer talent in electronic music.” At the time, only 18% of electronic music labels had women signed to them. Since then, Umfang has played Berghain, Hutchinson has helped get New York’s antiquated anti-dance law repealed, and women in electronic music have become more visible than ever before, with DJs like Nina Kraviz, Helena Hauff, Dr. Rubinstein, and Courtesy rising to household name status in clubland.

There is still a long way to go: the equality of festival lineups remains inadequate, while support for the “subcategory” of women DJs can often feel tokenistic. But increased awareness means people are at least held accountable for sexism and misogyny. Collectives like Discwoman have played a vital role in providing role models for aspiring female artists and creating spaces in which people of all sexual identities feel safe.

Nyege Nyege Hosts its First Festival (October 16-18, 2015)

Few would have predicted the enduring success of a spontaneous party thrown on the banks of the River Nile in Jinja, Uganda in 2015. Announced little more than a month in advance, the first Nyege Nyege festival featured artists from the United Kingdom, Ghana, Portugal, Burkina Faso, and Uganda, as indicated on its flyer (above). Within just a few years, writers were calling it the world’s best electronic music festival and it was being streamed live on Boiler Room.

Soon after its first event, the Nyege Nyege collective started a record label of the same name (and then another, which was equally good). The popularity of Afro-Caribbean rhythms in Western dance music has risen concurrently, thanks to like-minded labels like Príncipe, Fractal Fantasy, NAAFI, SVBKVLT, and Swing Ting, to name a few. Artists on these labels have riffed on kuduro, batida, gqom, kwaito, cumbia and many other styles—sounds primarily made either in ghettos (be they in Durban or Rio de Janeiro, Kingston or São Tomé) or by immigrants in Western cities forming bastard scenes through hybridisation with genres like grime and house. Many of these sounds have been bubbling for years, but it was in this decade that Western ears—perhaps due to a certain techno fatigue—lapped them up with glee.

Mica Levi Nominated for an Oscar (January 24, 2017)

Experimental music lost one of its shining lights in 2018 when Jóhann Jóhannsson passed away. After soundtracking a number of indie films through the 2000s, Jóhannsson’s scores for major motion pictures like “Prisoners,” “The Theory of Everything,” “Sicario,” and “Arrival” have defined the 2010s more than any other composer. As an experimental musician breaking into cinema, he paved the way for artists like Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (of Nine Inch Nails), Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow (the latter of BEAK> and Portishead), Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein (of Emeralds), Jonny Greenwood, Thom Yorke (both of Radiohead), and Daniel Lopatin (a.k.a Oneohtrix Point Never).

Mica Levi, of Micachu & the Shapes, provided the era’s standout experimental soundtrack with her Under the Skin OST, a record which has appeared on many end-of-decade lists as an album in its own right. Her next score, for “Jackie,” a tense, claustrophobic thriller about John F. Kennedy’s widow, was nominated for an Oscar and ushered in a new era for experimental music in film scores. Despite this success, Levi has resisted the lure of blockbusters and continued to work on challenging, independent films, such as this year’s chilling “Monos.”

Aphex Twin Plays Field Day Festival, London (June 3, 2017)

Richard D. James hasn’t actually released a classic album since the ‘90s. Yet his familiar ginger face has grinned back at us on many a music website throughout the 2010s. Why? Partly because we still feel it’s necessary to remind you all how great Selected Ambient Works was, but also partly because of his increasingly ingenious marketing strategies. He announced his only album of this decade by flying a blimp over London. His last EP saw sightings of his logo on billboards around the world send social media into a frenzy. Even his occasional interviews have been marketed like Hollywood films.

His bonkers DJ set at Field Day Festival in 2017 was his first performance in the United Kingdom for five years—first announced via a handful of scratchcard-style flyers that were dispersed at a market in London. Paired with an incredible light show designed by elusive visual artist Weirdcore and staged in a huge, purpose-built aircraft-hangar-style venue, it was among the greatest shows in the history of electronic music.

His subsequent performances at Berlin’s Funkhaus and Coachella Festival were met with similar hysteria. But they also started debates about how much he was being paid to play other people’s music, and how much coverage he was getting in the press. For some, James epitomises the 21st century “legacy artist”: an established musical titan dining out on past success at the expense of emerging talent. Contrast Aphex’s enduring career with that of say, Deapmash, whose track “Ballad 002” (a collaboration with Aquarian) has been played by Aphex. One is defined by six-figure gig sums and drip-fed releases; the other “stays broke forever.”

Photo | Amy Sussman/Invision/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Avicii Takes his Own Life (April 28, 2018)

“Mental health” has joined “music” in the same sentence with much more frequency over the past decade, a trend sparked by the death of pop star Amy Winehouse in 2011. However, it took the tragic suicide of Tim Bergling, the DJ-producer better known as Avicii, for the electronic community to really take notice, and since then the discussions of mental health in electronic music, and music more generally, have been commonplace on panels at conferences like Amsterdam Dance Event and Ibiza’s International Music Summit, where this year Bergling’s father, Klas, broke his silence and gave a passionate talk on the issue.

Within this past decade, Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington, Frightened Rabbit’s Scott Hutchison, South Korean singer Kim Jong-hyun, and The Prodigy’s Keith Flint have all taken their lives, and this is just the surface. Beneath these highest echelons you’ll also find artists who have lost their lives prematurely but accidentally, albeit wrapped up in anxiety and depression, and dependent on alcohol and drugs.

In November 2017, Lil Peep, real name Gustav Elijah Åhr overdosed on fentanyl and Xanax. Early last year, Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson was found dead in his Berlin apartment, the victim of heart failure after reportedly overdosing on cocaine. The mental and physical health of those in the music industry has been brought under a harsh spotlight this decade, but conversations like that started by Avicii’s death offer reasons for optimism.

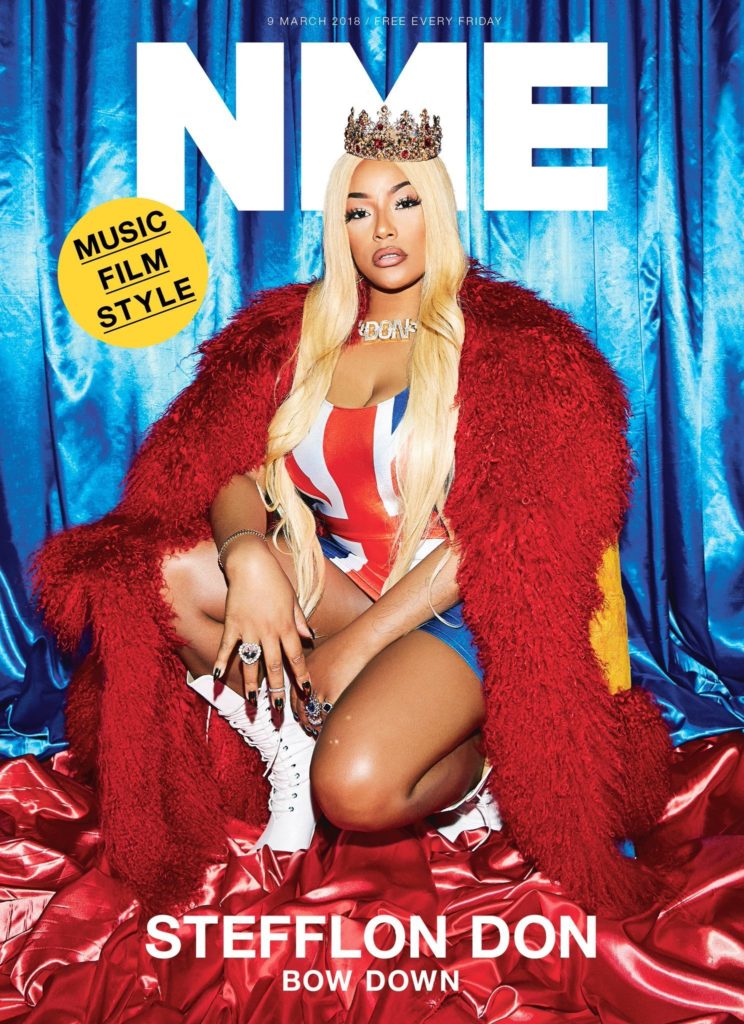

NME Publishes its Final Issue (March 9, 2019)

Music media continues to suffer, but let’s not get into all that again. When NME announced in early 2018 that it would be ceasing operations as a print publication, it confirmed what many had suspected for years. Due to missteps like placing Stormzy on its cover against his will and adamantly sticking by the Arctic Monkeys through thick and thin, the magazine had largely faded from relevance long before the death of its physical incarnation.

Many other music zines bit the dust this decade, but the end of NME—for so long the definitive voice on British music—felt symbolic. With it went any remaining consensus about indie music being the best sound around, instead allowing previously alternative outlets to push other, infinitely more exciting sounds like hip-hop, grime, and yes, techno, to the forefront of the public consciousness. The artists broadly believed to have defined the ‘00s were mostly white, middle-class and toting guitars. This decade’s concluding lists offer a range of ethnicities, backgrounds, sexualities and—crucially—instrumentation.

Gaspar Noé Releases “Climax” (September 21, 2018)

French auteur Gaspar Noé’s films generally range from chilling (“Enter the Void”) to harrowing (“Irreversible”) and “Climax” sits somewhere on the same spectrum. It is, however, marginally more watchable than the rest of his oeuvre. The film tells the story of a young, talented dance troupe throwing a party after rehearsal one night in an empty school, getting drunk on sangria which, as it transpires, has been spiked with LSD.

The “Climax” narrative spins on a 10-minute dance sequence, a mesmeric centrepiece during which characters take turns ducking, dipping, and death-dropping for each other’s entertainment. The scene recalls 1990’s “Paris is Burning,” a seminal documentary about ballroom culture in 1980s New York—which was also the inspiration behind Frank Ocean’s recently launched queer club night, PrEP+.

In its pairing of vogue-style dancing with a soundtrack featuring Daft Punk, Aphex Twin, Giorgio Moroder, and Dopplereffekt, “Climax” reminds us that club music is a product of queer culture. The film symbolises the overdue recognition of electronic music’s LGBT community in the latter half of this decade, showcased at events like NYC Downlow at Glastonbury, WHOLE Festival, and the world’s most famous gay club, Berghain, and personified by artists like Arca, SOPHIE, Honey Dijon, and LSDXOXO.

And sountracking that hypnotic dance scene? Not just one song but a mix performed live by gay DJ Kiddy Smile, between his track “Dickmatized” and Thomas Bangalter’s “What to Do.”

Nina Kraviz Wears Cornrows (October 26, 2019)

When Nina Kraviz posted pictures of herself wearing cornrows in her hair to Instagram and Twitter this year, she was condemned by many for misappropriating African culture. Having been worn as far back as the slave trade, cornrows are a part of black identity, not a costume for celebrities to try on like fancy dress. Kraviz didn’t help herself in her response however, lashing out at her critics and accusing them of “reverse racism.”

While electronic music has diversified significantly this decade, with greater numbers of women and racial minorities rising to the top of the scene, the Kraviz incident reminded us that we still have some way to go. The uncomfortable truth that techno, a genre brought into the world by black musicians, is now overwhelmingly dominated by white artists, is hard to ignore every time a “World’s Top DJs” list is published. But techno, as well as house, rave, and all club culture, was founded upon core values of togetherness, diversity, and the acceptance—nay, the celebration of difference.

The incident also exposed “cancel culture,” one of the decade’s most popular terms, as a fallacy: though many called out Kraviz on Twitter, she was promptly named in several year-end lists and her career has seemingly continued as normal. Many other disagreements have been aired on social media this decade—over the misogyny of Giegling boss Konstantin, the sharing of DJ setlists, and Sherelle’s Boiler Room reload, to name a few—but rarely have discussions ended in resolution. The growing prominence of more useful methods for debate, like newsletters and panels, suggests a brighter future in which the dance music community exists outside of Twitter.

And now to the future…

So dance music is bigger than ever. The new dawn promised by Skrillex, James Blake, and The xx proved largely accurate, with the mainstream now sounding infinitely more electronic than it did a decade ago. So what of the next 10 years? Are we to expect that, just as grime and dubstep went global in the 2010s, the 2020s will see a mainstream invasion from footwork and gqom? Will techno fade from relevance, stuck in stubborn insistence on rigid formularity and refined to the patronage of aging fans? And will club music restore the image of diversity upon which it was founded? It’s a strange time to be alive, but as the world crumbles, music will be more important than ever.

Editor Note: XLR8R staff would like to apologise for using an incorrect image of DJ Rashad. This has now been updated.