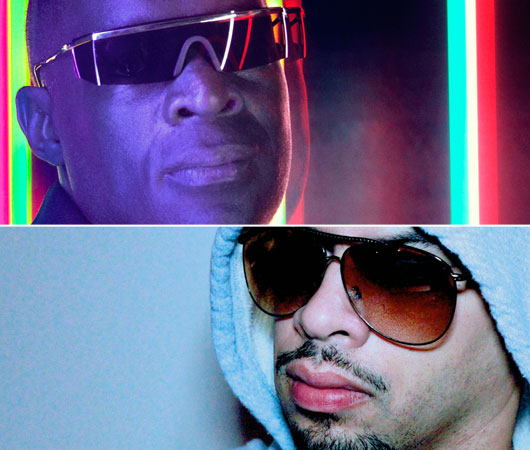

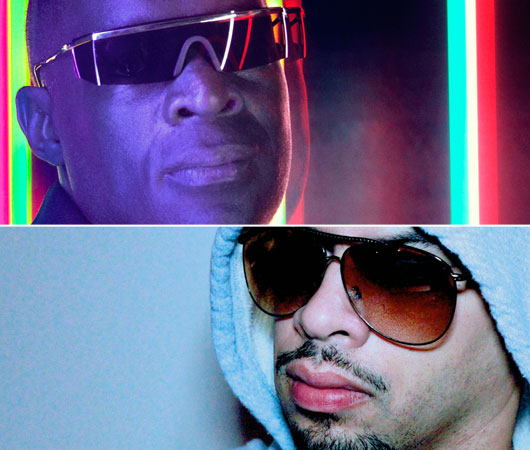

B2B: Kevin Saunderson and MK, Part 1

It’s fun to imagine that electronic-music legends all know each other, as if there’s some […]

B2B: Kevin Saunderson and MK, Part 1

It’s fun to imagine that electronic-music legends all know each other, as if there’s some […]

It’s fun to imagine that electronic-music legends all know each other, as if there’s some kind of social club for all those producers and DJs who helped shape house, techno, and all the other strains of dance music. Obviously, that notion doesn’t quite jive with reality, but in some cases, veteran producers actually do have relationships that stretch back decades. For instance, take Kevin Saunderson and MK (a.k.a. Marc Kinchen). The former is one of the progenitors of Detroit techno, one-third of the venerable Belleville Three, and the producer behind Inner City, Reese Project, and a litany of other endeavors. The latter is one of the key figures in the ’90s NY garage sound, and a producer who truly pioneered the art of the remix. Yet the pair first met more than 20 years ago in Detroit, when Saunderson was first exploding with Inner City and Kinchen was just another local kid looking to get involved. MK recently released a House Masters compilation for Defected, while Saunderson has an In the House mix slated to drop on the label in early 2012. As such, we figured now would be a good time to get the old friends on the phone to take a look back at their relationship and how electronic music has changed over the years. In the first half of this two-part conversation, Saunderson and Kinchen discuss how they first met, the explosion of dance music in the ’90s, and what it was like operating in a major-label environment.

XLR8R: How did you guys first meet?

Marc Kinchen: I don’t think Kevin and I have ever really talked about it, but this how I thought we first met. I did the “1st Bass” thing with Separate Minds, and Kevin, you heard it somehow, and you put it on your Techno-1 compilation.

Kevin Saunderson: Yeah, I think I do remember that.

MK: And that’s when I met Anthony [Pearson], Chez Damier. It was his suggestion to bring me in to start working with you.

KS: Right, right.

MK: That’s what I remember, this was 20 years ago, so…

KS: I know Anthony was around at the time, doing some A&R stuff for me, looking out for new talents. I think the connection definitely came through Anthony, that’s for sure.

XLR8R: Before you met, did you guys know anything about each other?

MK: Kevin didn’t know about me, because I was, like, 16.

KS: I definitely didn’t know about Marc.

MK: But I knew about him, because he was the biggest thing in Detroit at the time.

XLR8R: What were your first impressions of each other?

MK: Kevin was on top of the world at that time. He had just become major. So even though I was there with him, I wasn’t sure if he really noticed me that much. I was just a new kid. I wasn’t MK. I was nobody.

KS: With Marc, you could tell that he was a young kid, who wanted to hang around, doing stuff with Anthony, doing stuff on his own, very ambitious. Young, but talented. My doors were open to many people. He was talented and showed that he wanted to get down and do some things, and you could just feel it, feel the vibe. When somebody has that hunger to create, that’s a great thing, because everyone doesn’t have that inspiration. Marc, you were quiet, but you did your business. Once he started working in the studio, I could hear him working on stuff. At [that time], the studio was also where I lived. Marc used to come in and create in that little room, and I would be sleeping right next door. I was trying to get some sleep and you’d be banging it out, remember?

MK: [laughing] I remember that.

KS: He’d have all different kinds of hot shit. I’d be listening, and sometimes I’d want to get out of bed and say, “Hey man, I hope you’re keeping that!”

MK: I think you said that a couple times. You’d [come in] and I’d say, “No, I didn’t save it.” It’s weird, because we were both young. At least for me, I didn’t know there was a box. I was a young kid, just working on stuff, and I didn’t realize what was really out there.

XLR8R: What years are you talking about here?

KS: It must have been around ’88, ’89.

XLR8R: So was this at the same time that Inner City was really starting to take off?

MK: “Good Life” was already massive. It was all over the place.

KS: So it was definitely ’89, because “Good Life” came out right before Christmas in ’88.

XLR8R: When Inner City blew up and those songs became so big, did that change your perception of where dance music could go and the potential that it had?

KS: Inner City was an impression of me. When I used to go to the Paradise Garage, I heard underground records. I heard great disco records. I heard stuff like “Supernature” from Cerrone. So, my impression of music was always to be able to bring a vocal over a dance track. I liked Shannon’s “Let the Music Play” and stuff like that. So, I wouldn’t say I was surprised. Of course, I was surprised by the success, but people still like songs, people still like hooks. That was an important part of this whole process of making music, bridging what we were doing here in Detroit, and what some of the Chicago guys were doing, to a level where people would accept it more, without trying to sell out and sound like what was on the radio.

MK: The funny thing about what Kevin is saying is, that’s my same impression about doing house music with vocals. I was too young to go to clubs, but I loved what Kevin did during that time. What he did with vocals over house tracks, [that] is kind of what got me involved in it. I wanted to hear a certain type of vocals over deep-house tracks, and I got a lot of that from what Kevin did. I didn’t know he was inspired by the Paradise Garage and all that stuff, but it’s funny to hear that for the first time. I have the exact view that he has, but I’m just hearing it for the first time. It’s kind of crazy.

XLR8R: Marc, what prompted you to move to New York from Detroit?

MK: Out of Detroit, there was Kevin, Juan [Atkins], and Derrick [May]. Out of the three, Kevin had a sound that wasn’t so techno, as compared to Derrick and Juan. Kevin had a little deep-house feeling that I loved. That’s when I first started to realize how much I really loved deep house. I liked music coming out of Chicago and New York, especially. At that time, I was actually dating a girl that lived in New York, so with all the stuff that was going on, it just made sense to move to New York anyways. Also, “Burning” had just been signed to Virgin, and Virgin was out of New York, so it just made sense.

XLR8R: Moving ahead a little bit, it seems like the ’90s were pretty busy and financially successful for both of you. Kevin, you were doing KMS and Inner City, and Marc, you were doing all sorts of remixes and singles. What was that time like for you guys?

MK: For me, I saw a big window for all the dance guys. You could really capitalize on the market at that time. There was a lot of money being spent on dance music. It was new. It was loved all over the world. It felt like house music was going to take over. I just wanted to be a successful producer, any way I could. I was into deep house, so I wanted to make the best deep-house record I could. But I wanted to be compared to Kevin, Masters at Work, Todd Terry… I definitely wanted to be compared to the top producers. That was my goal.

KS: It was real busy. I was touring Inner City, [doing] Reese Project, my underground stuff. I was always active. The label was going, I was DJing a little, not a lot, but playing out. I was always touring and moving and before I knew it, it was the year 2000.

MK: The same thing happened to me. It did go by really quickly.

XLR8R: During that era, there was a lot more major-label interest, and it seems like it was a more commercial atmosphere. Is that true? What was it like working in that environment?

KS: I don’t know if it really affected me. With Inner City, I did have a problem with Virgin Records. “Good Life” and “Big Fun,” they were big club records in America, but they didn’t really cross over like they could have, like they did in Europe, to grow to another level. In America, to get to that level, [the label] really had to get behind it, and really push it in every aspect. Virgin just didn’t know and they were just happy with a dance record. With them, we had this thing where they said, “You should really be on R&B radio first, and then we’ll take you to pop.” [For me,] it was like, “What do you mean? It’s just a song that everybody can hear.” There were some real strange conversations when you had these labels that had a certain mentality of thinking, just on the way it can work. It wasn’t necessary, but it was what they were used to, and they weren’t willing to change any of those formats. That was the most difficult thing in dealing with them, but, in the end, I still made the music I wanted to make. I still came from a soulful background, from disco and all that, so, as I progressed and even started making different records—I did want to experiment with downtempo and stuff like that—I didn’t try and create anything that sounded like it was on the radio. It was always my own inspirations, and how I felt something should be created.

MK: Dealing with major labels and house music, a lot of the dance-promotion people that I dealt with were coming from the pop world. They didn’t get the underground part of it. So, a lot of times, when I would do a remix, I would do a plain vocal mix, and I wouldn’t go as deep as I really wanted to go, and I would use most of the vocals. Then, I would always give them two mixes. I would give them that [vocal] mix and I would give them a dub. The dub mix was always what I thought the record should be, where I knew that people would like it. Being 20-something years old, I had peers, and I knew what they liked. The funny thing is, nine times out of 10, the dub is what ended up getting played. The major label people, they didn’t know that. I would send them a dub, and they would almost not want to use it, because it was so different from what they were used to. With the chopped-up vocals and some shit being out of key, they didn’t get it. That’s what I dealt with.

XLR8R: What was remixing like during that era? Was it profitable?

KS: [The financial situation has] definitely changed as compared to now. Back then, when I did my first remix, that was the beginning of the reshaping of the remix. Before then, remixes were remutes or re-edits. When I did my first remix, on the Wee Papa Girl Rappers, that was the first remix where all the music was changed. I used a little bit of their vocals.

MK: That was one of my favorite remixes! Damn!

KS: That was the beginning. That was something else. I was put in this big studio, and didn’t know what the hell what all those buttons meant, but I figured it out.

MK: I didn’t know Kevin then, but I said, “Oh my God, this mix is insane!”

KS: My first remix, doing that, it was like cheating, because it was the beginning. It was with Zomba, which was Jive Records. I might have got 500 pounds back then, which was, like, 800 dollars. But, as things progressed, and I started to become popular in the remixes, because I was at the forefront of it, I saw as much as 40 or 50 thousand.

MK: Damn!

KS: But the average was probably 15 to 25 thousand, something right around there. People did get huge fees for remixes. Now, I know it’s back down. I have people wanting me to do remixes, they might offer me $1500, and that’s high. I just don’t really do any remixes, really. I might do some swaps with people I know, but I’ve been there, done that, and I really need to have a purpose or be inspired to do a remix these days.

MK: I’m the same way. The funny thing is, I don’t think my first remix really popped off that great. I was just getting used to it, and I moreso wanted to impress the person that hired me for the remix, instead of just doing what I wanted to do. Until I made my fourth or fifth remix, that’s when I started to do what I wanted to do. “Set Your Body Free” by Inner City was one of my first ones, but again, Kevin was my idol, so I didn’t go exactly where I wanted to go with it, because I didn’t want to scare him off. Later in the year, by the time I did the Reese Project’s “The Colour of Love,” I kind of understood the business a little better, and that was one of my favorite remixes for awhile.

Click here for part two of B2B: Kevin Saunderson and MK.