Rewind: Goldie

Goldie is the sound and the fury, a drum & bass icon who has done […]

Rewind: Goldie

Goldie is the sound and the fury, a drum & bass icon who has done […]

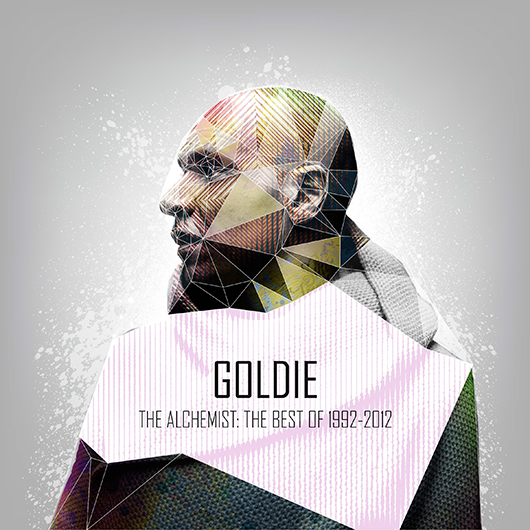

Goldie is the sound and the fury, a drum & bass icon who has done more than any other to put a face and a personality to a genre of music that grew out of chopping and grafting sped-up hip-hop, funk, and soul breaks. This week, he’s releasing a new three-disc anthology, The Alchemist: The Best of Goldie 1992-2012, and to commemorate the occasion, we asked the proud lion to give us the gold behind some of his most famous works.

It’s important to remember that Goldie was a hype graffiti writer and breakdancer before he ever hit the studio—he had been to the Bronx, chilled with Bambaataa, and painted whole cars before being inducted into the rave scene and introduced to Marc Mac and Dego of the Reinforced label via ex-girlfriend DJ Kemistry. (Though Kemi died in a tragic car accident in 1999, her memory lives on in “Kemistry,” one of Goldie’s most enduring classics.)

After several golden years on Reinforced (under the name Rufige Kru), Goldie parlayed his vision into big-budget studios, crafting the single “Angel,” the classic D&B album Timeless, and its mercurial follow-up Saturnz Return. In 1994, he started the essential Metalheadz record label, which has unleashed devious salvos from Dillinja, Digital, Source Direct, and Commix into the world. Though his personal life has often threatened to overshadow the music—there was his tumultuous relationship with Björk, his acting career, the legendary fights and debauchery—his tunes stand alone. At 47, Goldie has kept the faith of drum & bass while others have moved to greener pastures of house and dubstep, and as a result, he’s been rewarded with the undying love of the congregants. And even though he’s worked with different engineers over his career, including Technical Itch, Doc Scott, and Moving Shadow’s Rob Playford, the essence of Goldie’s signature sound—that trademark blend of beauty, menace, and b-boy flavor—always shines through.

“Music has become the alchemy for me,” he says as part of a rapid-fire rant that encompasses graffiti, Art Blakey, and breakdance tapes. “I can’t differentiate between fucking art and music and canvas and this whole thing. On a digital album that I made that never saw daylight called Sine Tempus, there’s a track called ‘Don’t Give In’ that says, ‘It’s nice to know that you are mine, my photograph of time.’ And that’s all my music ever was. It was just photographs, just to encapsulate how I was feeling at the time. And it’s really strange because people have really looked, have really listened, and they’ve really, really understood.”

Ajax Project Mach III EP (white label, 1992)

“My first ever record was the Ajax Project—it was a white-label collaboration with a guy from Iceland who’s no longer with us, a guy called B—and it was a Phil Collins sample with the Amen break. I remember cutting the fucking label with Ajax with a fucking potato [stamp], like a thousand copies of the white label, and we took them to a place called Mo’s Music and it blew up. So when it blew up, it pushed me towards Reinforced. I did “Krisp Biscuit,” “Killa Muffin,” “Darkrider” and “Sinister.”

Rufige Kru “Killa Muffin” b/w “Krisp Biscuit” (Reinforced, 1992)

When you were breakdancing, you just had lots of loops on a cassette—whether it was Channel Funk, the “Amen, Brother”… You had all these different breaks, and the tunes all of a sudden went from one thing to another. You go, “Well what the fuck has that got to do with this?” To be fair, the eclecticism of “Killa Muffin” and “Krisp Biscuit” was [the equivalent of] switching through a breakdance fucking demo test tape. It was like, “Here are some awesome, killer moves and let me show you what I can do with them.” It was like the difference between… okay, we’ve got bubble letters on the trains, but now let me show you some style.

Let me tell you this, when you’re not an engineer and you’re looking over the shoulder of a guy, that’s not different from me looking at a wall and knowing where all the perspective’s gonna fall and knowing where the outline’s gonna be and how much time I have and where I’m gonna lay things out. When graffiti writers get asked by the general public, “Where do you begin? Where do start? How do you make it that big on the wall?” that’s just down to your fucking third eye and the way you deal with perspective. For me, it’s the same thing. I was going in the studio with an engineer with my favorite music over that decade and from the decade before (which was where the melancholy came in), addressing it with some technical shit on top to cover it up and then coining phrases.

“Krisp Biscuit” was the name for a really fantastic E at the time. And “Killa Muffin” basically was… I used to go to this cafe and they had the most incredible kind of muffin with bacon and egg layered up. Every time I had a real kind of session and the next day I was feeling kind of sideways, I went to this cafe and had a killa muffin. And at the time, I was probably getting laid every couple of days, so “killa muffin” was obviously a name for the muff—a name for the pussy, my dear.

Rufige Kru “Darkrider” (Reinforced, 1992)

My thing was all about b-boy culture and having a crew. When I met these boys in Dollis Hill, Marc and Dego [of Reinforced and 4Hero], I thought what they were doing was brilliant. I was like, “Yo, I could make [the label art] look really good and give it an identity.” I said, “Yo guys, let me put a metal head on the dubplate label, so when DJs play our music, they know it’s a dubplate and they know it’s gonna be some trouble. They’ll know it’s us, they’ll know it’s our sign.” Reinforced was Reinforced, but there’s many a dubplate that got made where you had a Reinforced sticker on one side and then on the other side you had a fucking head with the headphones and the skull. It was a metal acetate with a skull, and that’s where it was coined—it was Metalheadz.

My college and university was Reinforced. After doing this artwork, I said, “I want to [make tunes] myself, so I’ll hustle the money,” and I took it to another studio altogether. My friends were doing stuff with a guy called William Orbit, and I just got together [with them] and said, “Yeah. I want to hire you guys.” I’d already had experience watching people like Howie Bernstein and Nellee Hooper doing the Soul II Soul stuff and I knew there was a certain kind of professionalism with equipment that they had. Being in the studio, I sometimes felt like I was restricted, like I had a lot of paint, but a very small fucking wall. With my ideas and their equipment, I had a whole bunch of paint and they had the right-sized walls that I could paint it on. So it was down to being a real b-boy and a real artist by going, “You’ve got fucking three days. You’ve gotta get the sounds that you’ve already collected and gone through in your head, you’ve got film clips, like Spike Lee and SOS Band and your favorite b-boy breaks, and you’ve got a day to arrange that and then you’ve got a day for those guys to mix it down.”

Metalheads “Angel” (Synthetic, 1993)

After the Reinforced stuff, I got approached by a company called Synthetic. And working with them was like, “Right, I’m in a big studio, I’ve got a budget of 10 grand, I am gonna make fucking some real fucking whole cars on this shit.” So then I just decided to songwrite. “Angel” is my first coining of a song, and “Kemistry.” And that was it. The rest is history, I guess.

I’d been making so many waves on the underground. I walked into KISS FM with “Angel” and said, “You need to fucking play this on the radio.” I had booked an appointment with a guy called Lindsay Wesker, and this motherfucker wouldn’t even play the record. He said it was too crazy, it was too much. If you play “Angel” now, it’s like a fucking pop record. So, you know, hindsight goes a long way. And I was just kind of street… Shit, I didn’t give a fuck then. I was trying to stomp people out, like, “This music is gonna be somewhere someday you motherfuckers!”

First, I’d been going around to all these fucking [major-label] record companies with artwork, and now I was going around them with a cassette with a five-minute record. I’m looking at these guys with all these pop promos on their desk, getting paid to listen to people’s music. I’m looking at these motherfuckers and I’m like, “This guy wants to go for fucking lunch. He has no interest in my music at all.” The guy would stop the cassette like halfway through and go [nerd voice], “Yeah, it’s great. Yeah sure, it’s fuckin’ great.”

I kind of made the whole Timeless project because I was angry with them. I went, “I’m gonna to make a record that’s 22 minutes long, and these motherfuckers are gonna have to listen!” And that was the bottom line.

Goldie, Timeless (FFRR, 1995)

Timeless was the mature coming-of-age album, which was gonna be inspired by every fucking genre—not just by Spike Lee and not just SOS Band, but by my entire life in terms of music. Whether it was fucking Mark Knopfler, Dire Straits, all the way through to Prince, The Stranglers to fucking Public Image Limited, it was all in there in some kind of rhetorical, archetypal way.

I discovered music all my life. I discovered Miles Davis’ “Decoy” on the back of a cassette tape given to me by 3-D [from Massive Attack]. I discovered Mingus through [documentary filmmaker/photographer] Gus Carol. I was sleeping on top of pneumatic tapes of Father Time with Art Blakey, hours and hours of footage of him playing fucking drums, only to look at those tapes and realize, “Wow, that was the pure loop!” I’m not getting it from the ‘Amen, Brother’ or from James Brown’s performance on video or the back of a breakdancing video. I kind of learned, culturally, very fucking fast, how important this music would be, and also what a design concept Timeless would be to where we are now.

I can quite clearly say that “Still Life” was Pat Metheny, man. You know, “Sensual” was inspired by Dire Straits. “This Is a Bad” was inspired by driving around a fucking city trying to find fucking coke, driving around and feeling the pressure from society. That’s what the lyric is: “This is a bad.” Like, “This is so bad! This society’s so fucked up!” It was that tension in the air. So, you know, “Timeless” being a three-part opus, which was “Inner City Life,” “Jah,” and then it was “Pressure,” which was feeling like I was in the Bronx or Hackney or Birmingham—this is about stacking society in a fucking tenement yard on top of each other and I’m scratching my head wondering why.

I think the music of Timeless was the soundtrack for the ’90s. Soul was Tricky. Soul was Björk. Soul was fucking Suede, Oasis, all of that. But the great thing about Timeless was that it was indie and drum & bass music and Portishead at the same fucking time. It was what happens to society when it’s left to cook.

Goldie “Kemistry V.I.P. (Grooverider Remix)” (Razors Edge, 1997)

“Kemistry V.I.P.” was probably the hardest and most unbelievable mix. That was the tune of Blue Note, actually. It was the soundtrack to [the Metalheadz club night at] Blue Note, followed closely by Dillinja’s “Silver Blade,” followed closely by Digital’s “Space Funk.” With Grooverider, I’ve always got my best work out of Groove from a remix point of view, because he knows me so well. And when you can angle someone’s work… I’m really proud of that. On the same note, I will turn around and say that Doc Scott’s version of “Kemistry” [FFRR, 1995], in an eerie kind of way, reminds me of [DJ Kemistry’s] passing.

I’ve given these loops to my favorite adversaries and my heroes. I’ll say this: if you make a ring and it weighs an ounce, there’s actually three ounces behind it. All of those tunes had so much behind them; they had the momentum of a scene, a genre, and they had the momentum of the arts, man. So the bar was set, and we never settled for anything less and we got the best.

Goldie Saturnz Return (FFRR, 1998)

Saturnz Return, in a nutshell, was the dark arts album. It was where I practiced my alchemy. You weren’t gonna get it. If you read a book called Kill Your Friends [by David Niven]—DJ Rage was me in that book. It was me going through my real period of darkness and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, but I needed to do that. I needed to make “Mother.” I was demonized and I fucking went through all of that shit. For me, when I watch When Saturn Returnz, the documentary, the album makes a lot of sense. It really sums up what I was about, and I knew I was gonna get crucified. But worldwide, it sold more copies than Timeless sold in Europe all together. That’s just how it was. If I had compromised my music, then you would have had Timeless 2, and I would be just painting by fucking numbers. Probably the best track on that entire album is on that first disc, where you have “Mother” and then you have “Truth,” which was written for David [Bowie]. Four minutes later, you have “The Hidden Truth,” the hidden track, which for me was probably one of the most seminal pieces of music I’ve ever made. Not that you’ll get it, but eat your fucking heart out, Philip Glass. That’s my contribution to what I think is cutting-edge electronic music that could easily be transcribed and notated into orchestra.