Deep Inside: Juan Atkins & Moritz Von Oswald ‘Borderland’

“This is my torture room,” Moritz von Oswald says, seated in his home studio. Technically, […]

Deep Inside: Juan Atkins & Moritz Von Oswald ‘Borderland’

“This is my torture room,” Moritz von Oswald says, seated in his home studio. Technically, […]

“This is my torture room,” Moritz von Oswald says, seated in his home studio. Technically, we’re in the torture room’s waiting area, a space outfitted with nice leather couches, a few test pressings, studio monitors, and a window onto the backyard garden that lets in a steady stream of birdsong and the sound of a brief downpour, the only respite from this muggy Berlin day. But the sounds that are pulsing from the studio—an extended rework of Model 500’s classic “Starlight”—where he, Juan Atkins, and engineer Laurens von Oswald (Moritz’s nephew) have been rehearsing the live presentation of Borderland, their new collaboration for Tresor—do not sound like the product of suffering. The album is an easygoing mind meld, a collaboration not out to make any particular statement but simply to see what arises. Oswald clarifies the nature of his studio practice in case his dry humor didn’t connect: “I don’t get in touch with nature here, I don’t get in touch with the family. Everything is separated. I’m the slave of this. It’s eating me up.”

Reprising their ’90s collaborations, Oswald and fellow techno architect Juan Atkins have made an album that’s necessarily bound up with the genre they helped define, but it’s also as far away as one can get from the meat-grinding sounds one is likely to encounter at Berghain. The album’s framework of hushed, steady drum beats and odd incidental sounds are immediately recognizable from Oswald’s recent improvised collaborations with Vladislav Delay and Max Loderbauer as the Moritz von Oswald Trio. After a career spent hammering out some of techno’s richest and most foundational textures alongside Mark Ernestus as Basic Channel and a clutch of other aliases, Oswald has arrived at a kind of clearing—his early Detroit influences have been aerated by dub’s spaciousness, jazz’s improvisational methods, and the microtonality of modern classical. But the leisurely—and, on “Treehouse,” deeply funky—exchanges with Atkins that ride on top give Borderland its added value and compulsive listenability. “It’s like a big universal force that says that these two guys are supposed to be together and make music,” Atkins says, describing the recording process. “You just go with it, you don’t question it or try to figure it out. You just do it.”

Borderland‘s actual catalyst, however, was Dimitri Hegemann of Berlin’s storied Tresor club and label; Atkins describes the album has “his baby.” In its original incarnation, Tresor, along with Ernestus’ Hard Wax record store, brought the Berlin-Detroit techno alliance into being. Oswald and Atkins have worked together extensively in the past, but only briefly as equal partners. The two met before Basic Channel started making records, through Ernestus’ work for the record store—the latter was was in contact with Detroit labels like Atkins’ Metroplex in the beginning of the ’90s, importing records directly. But it wasn’t long before Oswald started producing techno himself, and along with Thomas Fehlmann, he teamed up with Atkins to make a handful of tracks released by Tresor on the 1992 mini-album 3MB feat. Magic Juan Atkins. “Jazz Is the Teacher,” from that release, foreshadows what we find on Borderland to some extent. But the new album strikes out down a very different path, even factoring in the intervening 21 years of mellowing and refinement.

“I recorded a lot of tracks with Moritz when he had another studio,” Atkins says. “Dimitri gave us an excuse to reconnect. The stuff i did back then was really good stuff—I did the whole Sonic Sunset EP and a lot of the Deep Space album here. I don’t know why we hadn’t reconnected before now. The main difference now is that we’re both equal artists on the project. When I was doing it before, it was more or less my project and I was using Moritz’s studio and his gear. Therefore he was the engineer. He had a lot of creative input on those records, but it was unspoken, sort of in the background. And now he’s in the foreground.”

In person and on record, these two legendary figures—with over 50 years of work in the genre between them—are utterly straightforward. It’s not out of any desire to shut down expectations or puncture the myths spun around them, it seems, but more because the Hegemann-midwifed collaboration came about simply and the work happened naturally. If it’s easier to discern Oswald’s sonic signature in the music itself, Atkins’ buoyant contributions are unmistakable when the listener relaxes their ears and starts to go with the album’s unhurried flow. Although Oswald says he’s able to disconnect from nature in this garden-adjacent studio, Borderland is lush and organic in a way that his Trio albums aren’t. The fusing of the two talents is so seamless that describing where one starts and the other ends is bound to be conjectural, with the exception of “Treehouse”‘s jaunty organ riff—that’s definitely Atkins. As a general note, it’s safe to say that Atkins’ funky, harmonically rich sensibility contributes a warmth and approachability that’s absent on those Trio records.

More interesting than trying to trace back each producer’s contributions is the idea that both are subconsciously channelling the vibe of Berlin’s numberless, sprawling parks and suburban gardens into the meditative spaces on the album. Borderland revolves, after all, around various versions of the inexhaustible “Electric Garden,” which juxtaposes a rolling dub bassline, non-tonal chirps, and a waving, flanged horn fanfare that recalls Oswald’s and Carl Craig’s deconstruction of Maurice Ravel’s Boléro. This track, in its various forms, accounts for nearly 40 minutes of the hour-long album.

“Do you know the composer Olivier Messiaen?” Oswald asks, on the subject of the sounds issuing from his backyard. “He transcribed the birds into orchestral music. This is something that is so beautiful, and it’s very difficult to perform, but not to listen to. It’s so spacey in a way. There’s so much sound power in the openness of the way they’re living, these guys—you can hear it. They really communicate. One is doing [whistles] and the other one is [whistles again]. It’s like back and forth. How they do it is so light. This is what I like in music, is if it’s light. If music is good it should or it can be light, like just floating. I think all these birds are girls. Girls’ music, I think, is something we almost take for granted. If girls like the music—not girls, but females—if they like the music then it’s good. And then it’s good for me because it has this lightness, from my point of view.”

Messiaen was a composer whose sometimes difficult, always otherworldly music derived from humble sources—his Catholicism and his synaesthesia—rather than a desire to keep up with the avant-garde of the time. Without the religious overtones, an uncomplicated wonderment seems to be behind Borderland too, and the results don’t fit neatly anywhere outside of its creators’ discographies.

If Tresor’s initial iteration was associated with hard techno, how is one to describe the current trend for still-more-industrial sounds in clubs, particularly in Berlin? The lightness Oswald speaks of is conspicuously absent, something which could be interpreted as the a result of DJs staking out ever-smaller niches, carving out an identity while catering to an underground that’s hardly as underground as it was when the Berlin Wall fell. It’s not as if Borderland doesn’t have its dancefloor moments, but in most meaningful respects, it’s a home-listening record. The duo, assisted by Laurens’ live mixing skills, recently debuted the project live at Montreal’s MUTEK festival. “It’s gonna be the same feeling,” Atkins says of the live show. “I was just listening now and the tempo on a couple of tracks is gonna be a little different, to make it more danceable in a way, but it’s funny because it’s nothing we think about. People have been able to live with techno music for the past 15, 20 years, so it’s like we’re more comfortable—we’re not thinking so much of how is it going to come across just because it’s so new. It’s like, ‘Okay, let’s relax now.'”

The recording of the album was an equally unfussy affair. “We do not work in the pop business so we cannot plan things,” Oswald half-jokes. “It was more like, ‘Okay, let’s mix it together and see what we can do.'” The two are cagey when it comes to the specific combination of software and hardware they used to create the album, but are quick to praise Laurens’ engineering skills, in particular his ability to be transparent while holding things together. The idea of a live jam is often trotted out to reinforce some notion of raw, in-the-moment authenticity, but Borderland is compelling because it’s both immediate and polished, spontaneous and seamless. “It’s amazing to me,” Atkins says, “I think Moritz works a bit faster or easier in that respect, whereas I’d probably still be working on the record if it was up to me. So he says, ‘Hey, should we mix it?’ and I’m like, ‘Are you sure it’s ready to mix now?’ But we just did it as soon as it was ready. It feels better when you don’t put a lot of thought into doing things. When you know everything—when you know what’s going to happen ahead of time—it takes the fun out of it. I like to keep it fun. The way I keep it fun is to not know everything.”

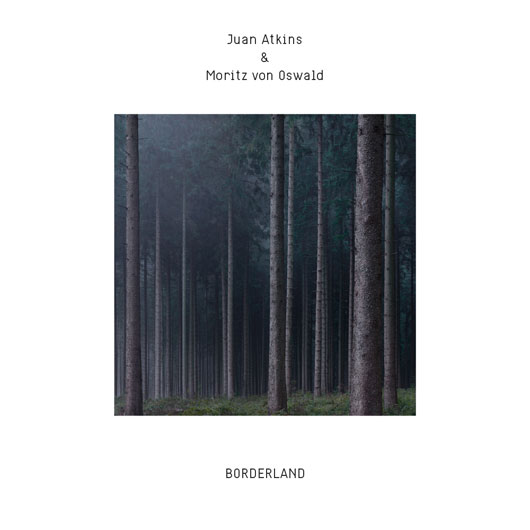

This combination—Atkins’s practical mysticism and Oswald’s ductile minimalism—makes Borderland feel earthy and enchanted at once, playing off the misty forest pictured on the album’s sleeve art. This quality of in-betweenness—the record can be triangulated somewhere between Model 500’s spaciest classics, the gratifying, if austere, precision of Oswald’s recent output, and Hegemann’s curatorial acumen—is the only conceptual framework adaptable enough to contain these quicksilver jams that levitate between dissonance and harmony, rhythm and drifting ambience.

This brings Oswald back to Messiaen: “This composer is so special… usually what I also like about him are dissonances. This is something that’s maybe getting on live, not clashes but just… this kind of thing. I think this record is quite harmonic, in the music, texture—not disharmonic, like clashing or whatever. This is what appears in Messiaen’s music as well, these kind of… I also described it on Trio releases as ‘non-tonal structures,’ which means just the structures in between the tones or notes—cymbals or things that are not determined to have a note, like a C. Just between these things that I sometimes hear in music. That’s why I really like the ring modulator, the bell sounds that it’s creating, like noise or overtones, but not really clear, it’s just quite… different. You cannot really hear it as a note. I like that a lot. This way, the music is always given some room or some freedom or space to develop. This was something I tried to approach with Basic Channel, to give the sounds so much richness that it’s unique. I didn’t try to do that on purpose here, but it’s something that attracts me a lot.”

Neither Atkins nor Oswald is able to explain the 21-year hiatus between 3MB and Borderland, but the timing is fortuitous for everyone involved, not least Tresor. The club was forced to close its original location in 2005, and reopened in a very different landscape in 2007. The label has continued to put out new releases, but Borderland brings things full circle in an unforced way. It not only reaffirms the Berlin-Detroit alliance the club pioneered, but also rethinks the shape that sonic and cultural exchange can take, for diehards and a new generation of electronic-music fans alike. And it does so without trying particularly hard—or at least it hides its tortures very well. What Oswald says about moving his studio from Kreuzberg to its new location in a calm, leafy neighborhood—”It came along like a routine to change the environment”—applies equally to the morphing landscapes of Borderland.