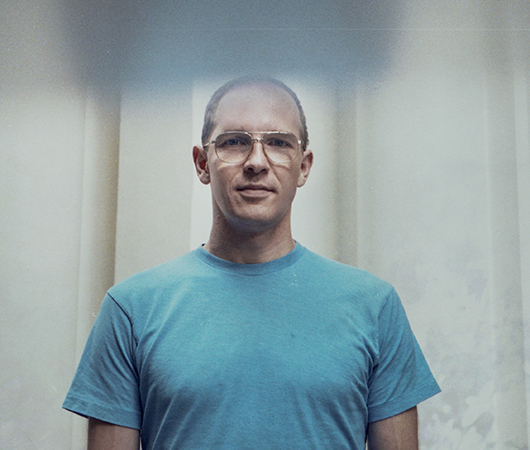

Rewind: Caribou

Dan Snaith has a history with making music that reaches back to his mid-teens, but […]

Rewind: Caribou

Dan Snaith has a history with making music that reaches back to his mid-teens, but […]

Dan Snaith has a history with making music that reaches back to his mid-teens, but he didn’t actually get his start as an artist until the age of 22, when he wrote a track called “Anna and Nina” for the Leaf label’s third Invisible Soundtracks compilation. “The music I was making before that point was terrible,” the Canadian musician, singer, and mathematician remembers with a chuckle, quickly adding that he’s happy no one ever released his earlier songs. “I knew there had been a change from what I’d made before. I thought, “This is something that I don’t feel embarrassed about playing for people, and someone might want to put this out.” Humble as he is, Snaith was unwittingly at the precipice of a 14-year career as an artist when he finished “Anna and Nina” in 2000, and would eventually come to establish himself among the most beloved names in indie and electronic music alike.

The details of how Snaith became the incomparable producer we now know as Caribou paint the picture of a man who has more or less been figuring things out as he goes. Over the course of six genre-juggling albums (including the soon-to-be-released Our Love LP), Snaith has stumbled onto a record deal, reinvented himself, fielded a pointless and debilitating lawsuit, won a national award, reinvented himself again, and gradually realized just how much his fans adore everything he does. He’s illustrated these formative experiences in his own words for the latest installment of Rewind, effectively explaining how 14 years of trial and error, hard work, and self discovery have enabled him to write his most personal and emotionally generous album to date.

Manitoba “People Eating Fruit” 12″ (2000)

This was the beginning of me releasing music, basically. Everything was totally unreal at that point, because [Leaf was] based in London, so I hadn’t even met the people that were releasing my music. It had been hooked up through Kieran [Hebden], Four Tet, who I’d met at the Big Chill festival in the UK. We got along well enough that I sent him an email after I was home [in Toronto] inviting him to play one of our parties. He’d never really traveled to DJ at all at that point, so he thought it could be fun. I was like, “I’ll pay for your flight and I’ll put you up on our couch.” So he came out and stayed for like a week, and I started to play him music that I was making at that time. And he was like, “I think this is good, and I can pass this along to some of the labels that I’ve been in touch with.” So he passed it along to Output, which is the label that put out his early stuff, and they weren’t interested. Then he passed it along to Leaf, which is the label that actually passed over his first release, and they were into it. It was such a weird time, because I’d get mailed to me clippings from NME that were like, “This newcomer’s single is out, and it’s a blend of this…” And I’d be like, “What?!” [laughs] It was so unreal, because no one in Toronto knew anything about my music.

Manitoba Start Breaking My Heart (2001)

I went over to London in the summer of 2000, around when my first EP came out, and met the people from the label, hung out with Kieran again, and worked this math job at Hewlett-Packard. It was a total dream for me; the only thing I had ever wanted was to have my music physically released. That’s when things started to work, and I had an idea of what I wanted to sound like. In some ways, it was very much influenced by what Kieran was doing, Boards of Canada, and those kind of things, but also sampling off a lot of old records and things like that. It’s a really nice time when you’re making your first record. I didn’t even think that I was making a record. People from Leaf would just ask for more music, and I’d be like, “Oh, they want more music. Okay, let’s make some more music.” And I’d send them and Kieran some more music, and they’d say, “Oh, these two tracks are really good. Send us some more music.” I didn’t really know how it worked. I would’ve been doing it anyway, but now there was this added kind of impetus, this added point to doing it.

I actually made a whole other record in between Start Breaking My Heart and Up In Flames. I mean, it wasn’t very good. [laughs] My greatest fear at that point was that if I don’t follow up [my first album] straight away, everybody is going to forget about me and this was all going to be over. Things moved way more slowly then, but I still had the sense that I had to act fast and keep people interested somehow. So I thought, “People like this first one, I’m gonna make some stuff that kinda sounds like the first one,” which is a terrible trap to fall into. And so I did that, but I had this record that didn’t excite me in the way that the first one did. I realized that if I’m not super into the music, I shouldn’t be releasing it. And that decision probably put me in a good position for the rest of my career. I thought, “From now on, only shit that I really stand behind will be released at all.”

Manitoba Up In Flames (2003)

I had been making music to sound like my first record, but I was more excited at that time by rare ’60s psychedelic rock, bands like Aphrodite’s Child and The Millenium with this big, cacophonous sound. It was so different from my first record that I was afraid of what people would make of it. It wasn’t even in the same genre of music, almost. Then I kind of duped myself into thinking, “I’m just going to keep making this kind of music, but it’s just going to be for me, I’m not going to release it.” I made the whole [Up In Flames] album in that mindset, which maybe was just a way of tricking myself into getting rid of those anxieties and the feeling of having pressure on me. Inevitably, though, I played it for Kieran and Tony [Morley] at Leaf, and they were like, “This is obviously the next record.”

In March of 2003, Up In Flames came out, and then that September we went on a little headlining tour of the West Coast in North America. At the first show in LA, we were soundchecking in this little club, and the promoter came up and said, “Somebody who knows your brother is at the door.” And I don’t have a brother. [laughs] But I went to see who it was, and the guy said, “Sorry, you’ve been served.” [Handsome Dick Manitoba] had previously emailed the label saying, “You’ve got to stop using this name [Manitoba] now.” And I just thought it was ridiculous, so we ignored it. But when I was served by this guy and I opened it up, I was like, “Oh, this is real now.” Everything at the moment was just like… It all melted. It was very disorienting, playing that show was a bit weird.

I thought I’d talk to a lawyer and they’d say, “No one will actually get confused between a solo side project of a guy from a punk band and this electronic music. Nobody is actually going out and buying the wrong records, so what’s the problem?” But the lawyer actually told me that we had a 50/50 chance. He said, “We could fight this court case all the way, and the judge could be like 80 years old, not have listened to any music for the last 50 years, and just be like, ‘Well, this looks confusing to me!'” Or we could’ve won, but I would’ve spent like half a million dollars. That was the end of it, because I didn’t have anywhere near that amount of money. So I was just like, “I gotta wrap my head around this, I’m changing my name now.” And it actually ended up costing me like $20,000 just to do the paperwork saying that I would change my name. I don’t know what he hoped to achieve by it, still to this day.

Caribou The Milk of Human Kindness (2005)

We announced the name change before I made The Milk of Human Kindness, so people would have a while to get used to the idea. When it was announced, everyone online was like, “This is some bullshit. I can’t believe this one independent musician who is not losing anything is suing another musician just out of ego.” Even on his message board and website, people were like, “You’re a piece of shit.” I got so much positive feedback when I changed the name, and that’s what “the milk of human kindness” refers to. It’s about the people who were willing to stick with me and support me. We hadn’t toured that much, and it was before the internet became what is now, before that kind of immediate communication. So it was always very abstract whether or not people liked the records, whether it was connecting with anybody at all. Changing the name was the first time people would go out of their way to communicate their support, and I definitely felt that. That was part of what made me want to keep at it, and put everything into making the next record.

Caribou Andorra (2007)

All of my favorite musicians up to this point were outsiders, people who never sold a lot of records or achieved critical acclaim in their lifetime. It was cult music. As a record collector, I was always searching for things that had kind of failed at that time but were amazing. So that’s what I aspired to, to be a failure. [laughs] The Polaris was very much like being welcomed into the fold, at least with Canadian music. I heard about the nomination and went to the awards ceremony, but didn’t really expect to win. But even when meeting all the other bands, many of them were saying, “I really like [Andorra]. I hope you win.” It made me think, “Wait a minute… I’m not really the outsider that I thought I was.” And then actually winning [the Polaris] obviously was really nice, and also overwhelming. But at the same time I thought, “This kind of thing doesn’t actually have an impact on what I’m doing musically, and it’s not why I’m making music.” It’s kind of a funny thing, isn’t it? What relation does it have to the actual, bedrock reason I’m making music? The answer, I think, is not really much. I didn’t set out to sell records, I didn’t set out to get acclaim or get fame—none of those things were really important to me at all.

Andorra was the first time that I tried to write songs, like I became interested in songwriting. Before then, it had all been about production, all about capturing some sort of visceral live energy, making some crazy racket. I had been listening a lot to people like The Zombies, classic songwriting things. When I made Andorra, I collected a long list of songs that I thought the lyrics, melody, and harmony underneath everything was really well composed. That had never really been important to me before, but became the whole focus of Andorra. And I guess that makes it more poppy, more accessible. Every song on that album has vocals, I think, and every song has like a verse and a chorus. I guess, in some ways, that made it more traditionally conventional.

Caribou Swim (2010)

One of the times that the sound of my music changed the most was between Andorra and Swim. I needed to kind of stop and take stock of what I wanted my music to be like and sound like, and that change took a while to figure out. It started when I was finishing Andorra—the last track is basically a James Holden pastiche. I’d become obsessed with his music. While I was making Andorra, The Idiots are Winning came out, and I’d already met [Holden] and seen him DJ. I thought he was doing something really exciting. So you can kind of see the end of Andorra leading into the beginning of Swim, and how I was starting to think more in terms of dance music again. My friends were becoming interested in dance music again, and I had new friends, like James, who were dance music producers. While I was making Swim, I got to know more people like Floating Points and the Hessle Audio guys; Swim was very much a London-centric record. I also went to see Junior Boys play at the Barbican Centre—they were opening for Liquid Liquid—and that was when Kieran said, “Hey, Theo Parrish is playing at Plastic People.” We all went down there, and we actually walked in while he was playing a Liquid Liquid track.

That night changed everything for me. I think I went home and made “Bowls” immediately after that. It gave me a whole new perspective, because I began making music for a different space, a different kind of soundsystem, a different intention. It kind of reinvigorated everything. And at the time, between 2009 and 2010, there was so much good music happening in London—exciting things kicking off in small clubs, big tracks, new labels. That’s what the impetus for Swim was, for sure, but it’s still transitional. There’s still the kind of psychedelic, echo-y effects. It was a big surprise to me the way that it connected with the dance music world. When it first came out, one of the first things I saw was Carl Craig tweeting like, “This new Caribou record is wicked.” He’s one of the primary reasons I was trying to make music that refers to dance music, and I was just like, “That was quick!” [laughs] It occurred to me that the people I like in dance music aren’t just listening to dance music, they’re listening to all sorts of stuff. That’s probably why [the album] was able to move into that world more than I thought it would.

Caribou Our Love (2014)

With Swim, I started to get the sense that some of my psychedelic records refer too much to old music, they’re too much a version of me trying to do something old. In all of the music I really love, people are looking forward, looking to get their own sound and do their own thing. And that’s when it started to become important that I make [music] sound like me. It’s got a dance music influence, but it also has to be my own thing. So Our Love was a continuation of that trajectory of trying to make my own thing and make it contemporary. In some ways, it’s not that connected to what I’ve done in the past, but I’ve also realized over the years that, even if I didn’t try necessarily, there are things in my music that are characteristic of me—the kinds of melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and things. It’s hard to articulate, but there’s something about them that is characteristically me.

In some ways, Swim felt like a new start again, things had kind of changed again. And yeah—this seems to be a theme—it gives me a lot of impetus when I feel an affirmation of some kind from the people listening to my music. The difference this time was that the response to Swim made me think, “I want to make a record for these people, for everybody that’s going to hear it.” And that thought had never crossed my mind before. But it wasn’t about making music that I thought would be populist, or that I thought would be lowest common denominator. It was about realizing that people were interested in what I was doing anyway, and so it was about making a record that had as much of me—my sound, my personal life, my everything—in it. And with the intention of it being something of myself to share with people, making it as much of a representation of me and my life as possible.