Beats in Space: An Oral History

This month marks the 15th anniversary of Tim Sweeney‘s seminal radio show Beats in Space. […]

Beats in Space: An Oral History

This month marks the 15th anniversary of Tim Sweeney‘s seminal radio show Beats in Space. […]

This month marks the 15th anniversary of Tim Sweeney‘s seminal radio show Beats in Space. Beginning as an inauspicious weekly gig where Sweeney played records he loved to an audience that may or may not have been tuning in, the show has gradually developed into a global institution, playing host to many of the world’s finest DJs and reaching listeners far beyond the small New York University basement from which it is broadcast. Last week, Sweeney issued a two-CD mix compilation to commemorate Beats in Space’s 15th birthday, but we wanted to find out more about what’s involved in keeping a radio show on the air for so many years. As such, we caught up with Sweeney and a cast of characters involved with the program throughout its run to discuss Beats in Space, its history, its legacy, and what exactly makes the show’s unique host tick.

THE EARLY DAYS

Tim Sweeney: In high school, I was really interested in radio. I actually played at a couple of different college radio stations. University of Maryland, Carnegie Mellon… I grew up in Baltimore. Between my junior and senior year [of high school], I went to New York, and I played at WNYU. I knew about the station, I liked it… so when I ended up going to NYU to study, I got in touch with the radio station and asked how I could get started on my own show. They kind of fast-tracked me with getting started, getting a show.

Bryan Kasenic (owner and operator of The Bunker): When I started there [at WNYU], I moved to New York and started NYU in summer of ’97. I don’t remember exactly when I started having a radio show, but I got involved in the radio station right away, which probably would’ve been like fall of ’97. From what I remember, Tim was starting out at exactly the same time as me. Same semester, the semester before or after. You would get an AM, they called it that, separated between AM and FM. We were booked doing AM shows. We were starting there around the same time… [Tim] and I both filled in for Neil Aline.

Tim Sweeney: It was called BPM. It was run by a guy named Neil Aline. He’s now the booker at The Standard.

Bryan Kasenic: I feel like maybe I was the guest host, but [Tim] came in and DJed half the show. He was playing as The Professor. His DJ name was The Professor at some point. He was playing more drum & bass at the time. But that would’ve been pre-’99, before he even started Beats in Space.

Tim Sweeney: In high school, I went by the name The Professor to sound older, so I could DJ at clubs… Then a 16-year-old would show up and they wouldn’t know what to do…

[The music I played] was a lot of IDM-type stuff. Warp Records things. And a lot of stuff from Mo’ Wax, Ninja Tune, and some more hip-hop things…

[Growing up, my older brother] would bring back some tapes to the house, and then he started buying records, electronic music records, and from there I just got hooked on it. And that also kind of got me started on the radio—the tapes he’d bring back, he got pirate radio shows from London. I remember hearing the Coldcut Solid Steel radio show, and those kinds of things really got me interested in doing radio as well…

[Beats in Space started] in September of ’99. That was my first year of college. I was studying music, music technology. I played some piano, some saxophone. I played sax on the DFA remix of Radio 4’s “Dance to the Underground”…

I just wanted to do my own radio show. I wanted to try and do my own thing and do it every week, do my own show. I didn’t really have any expectations for it. I just wanted to get listeners… and kind of see if I could get it to grow. It wasn’t like I thought I was going to do it for 15 years or make it into something huge, you know.

Bryan Kasenic: You know, I think for anybody involved in college radio—you need a certain level of precociousness. You show up, and you’re like, “Hey, I want to be involved.” And nobody is ever impressed at a college radio station. You kind of have to be like, “No, I’m really interested.” And keep showing up, and keep doing stuff. So anybody who ends up with an actual show at most college radio stations has to be on some level a go-getter, because if you’re the kind of person who easily gives up, then you’re going to give up pretty fast when you’re like, “I showed up, and nobody was excited that I was there. Nobody seemed to care.” The 10:30 p.m. to 1 a.m. weekday slot was kind of dedicated to electronic and club music. I would imagine somebody probably left… and if Tim was still—he must have like, basically, hung around from when I was there in ’97, that’s what I mean about the kind of dedication it usually takes to get a show.

Justine D. (a.k.a. Justine Delaney, New York City party promoter and Tim’s former girlfriend): When I met Tim, Tim was a senior at NYU. At that point, he had been doing Beats in Space since the beginning of college, I believe. You know, [the show] was something that Tim really looked forward to doing on a weekly basis. When I met him and for several years after that, he wasn’t a traveling DJ. He was really based in New York City completely, and Beats in Space was his home away from home. I think WNYU was definitely his calling at the time, and it’s really what he put the most focus on.

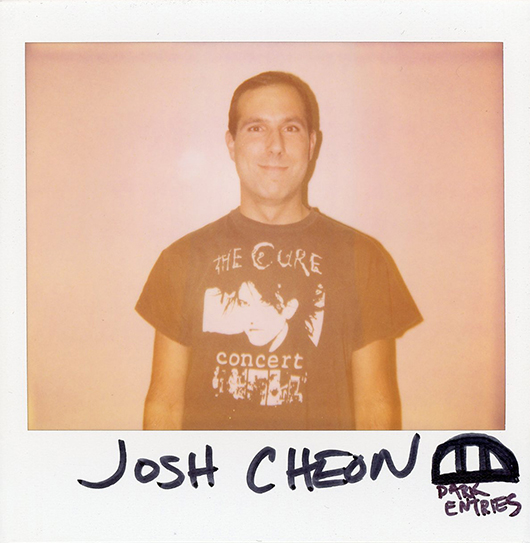

Josh Cheon (owner of Dark Entries Records, Honey Soundsystem member, former DFA intern): He was dating Justine D., who was throwing the Motherfucker parties that were always on three-day weekends, on bank holidays, so we’d always have off on Monday. Sunday night would be a giant crazy party and the music was post punk, new wave, glam, electroclash, just dance music—everything from David Bowie to Miss Kittin, then they’d play a Ministry song. It was just so much fun. It was thrown by Michael T., Justine D., and a couple other people. Tim was dating Justine at the time, so they were like this power DJ couple. They’d be amazing. Sometimes Tim would guest DJ. I always saw him as this sort of… he could play anything from hip-hop to house.

Tim Sweeney: In the early years, what was nice about [DJing on Beats in Space] was really similar to how I was DJing in my house—no one around, playing music. But, you know, you do actually have an audience, so it was nice. It wasn’t too nerve-racking. Early on, it was just me. It actually hasn’t changed a lot, but in the early days, it was just me all the time. Now I have too many guests and don’t get to play as much. [laughs]

THE GUESTS

Tim Sweeney: I think the first guest was actually DJ Food. I think they were coming to New York for a show, and I emailed the record label or emailed them somehow, I don’t remember exactly. And I just asked if they would be interested in coming on the show. And I knew they were radio people, because of Solid Steel, and that it would make sense. It was awesome. I was really young then and super nervous, but they were really nice guys and had been around for awhile, so they were just happy to be on the radio in New York…

I would say it was a trickle into a river, you know. The beginning, it was maybe one every couple of months. I think the next people I had were In Flagranti.

Prosumer (a.k.a. Achim Brandenburg, Tim’s most frequent radio guest): I met Tim when we had been in touch through email, so the first mix recorded for Beats in Space was actually just me sending a mix over… and meeting him [in person] for the first time was my first real Beats in Space appearance, so, yeah, I met him in front of a university building in New York.

JD Twitch (a.k.a. Keith McIvor, half of Optimo, frequent Beats in Space guest): I can’t even remember [when we first met]—it was way back in New York. Tim used to have a girlfriend named Justine, and she had us play… And that’s maybe how we first met Tim. We got in with the DFA crew and Tim had just finished interning for them. Maybe we met him from hanging out with them. And he’s been such a good friend of ours ever since, it’s hard to pinpoint when we first met.

Justine D.: When it’s just Tim spinning, which is how it was in the early days, it was like a lone wolf playing records for himself, which is kind of the ideal situation if you have somewhat underground taste in music. You’re in a small dark room and able to play records and somehow magically it reaches hundreds and thousands of people online. It was very intimate back in the day and a few years later, he started to have a lot more guests. It became a bit of a social event, depending who was spinning with him. It was like hanging out with friends basically.

Mike Servito (resident DJ at The Bunker): I don’t even know the first time I met Tim. I’m sure I met him at a party. The first interaction with him besides a hello was him inviting me to come and play. It was late 2013, September. I played for him the first time September 2013. We had done an anniversary party, we had both been booked for Discovery [a party in New York]. I don’t know if it was timing or what, but he had emailed me and asked if I wanted to be on the show. We weren’t really friends or close at all, but have become very close since then. I’ve always kind of paid attention, but there was never really anything past a hello. I mean, it’s Tim Sweeney. You have a preconceived notion of people that have long, lustrous careers. It’s crazy…

[We hit it off because] the same girl cuts our hair. He mentioned it to me upon our first interaction, and we grew close over the past year or two. We definitely—our interaction is very different now than when I first met him. Lots of joking, goofing off. He’s a really great person, really easy to get along with.

Kim Ann Foxman (DJ/producer, former member of Hercules & Love Affair): The show totally—it really opened up a broader audience for me as a DJ, which was great. I had been DJing in New York for a long time, but I was just starting to play out, fly places. I was in Hercules, but I was … people didn’t really know that I totally knew how to DJ, even though people in New York knew me, you know? So I played on the show, I played all vinyl, and all of a sudden, … I got booked in Ukraine and Russia, and all these places that I didn’t know that I would be booked. It was awesome. A lot of people listen to that show. Of course, you know, the exposure of Hercules—once people actually heard me DJ, being a person that people only know from a band, it’s like they’re not going to assume that you know how to DJ. They probably assume that I’m a personality DJ. [laughing] I got more attention for my DJ skills after that.

Ron Morelli (DJ, owner of L.I.E.S.): I couldn’t even say [when I met Tim]. It was a long time ago. It must have been at some point in New York. Everything’s a blur at this point. It could’ve even been at some punk show or something like that. I just know it was in the early 2000s. [The range of Tim’s guests] spans so many different people—from someone like Marcellus Pittman or Anthony Parasole to someone like DJ Harvey or Eric Duncan or Lee Douglas, or Andy Weatherall, it goes all over the place.

[The show] definitely is very New York. He’s bringing a lot of characters from New York onto his show. He’d have people like Brendan Green on his show, who’s a complete character. The best shows to me are all the ones who have a colorful personality who will joke around. Brendan’s shows are always good for that. Or he’ll have Eric Duncan on the show. It’s an important platform to have there. Without that, there’s no voice for—as much as people think there’s such a huge, vibrant scene in New York… and of course there’s Will Burnett who has his show, which is cool, but it’s not on the same level. It’s not in the NYU basement. It doesn’t have the scope or the following that Tim’s show has. It’s important that [Beats in Space] exists, I think.

Jay D. (a.k.a. Jeremie Delon, long-time staffer at A-1 Records in the East Village, where Tim shops for records every week before the show): [I guested on the show] two years ago with Ron Morelli. We talked a lot of smack on the show, as you do. [Tim and I] have been seeing each other for like 15 years now. It’s almost like getting to know each other. We live in the same neighborhood, so it’s beyond the music thing. It’s a friendship. It’s easy, it’s fun, we had a good time. We played some records and talked shit, in a non-judgmental way, more of a playful way.

BEATS IN SPACE: THE SHOW, THE INSTITUTION

Tim Sweeney: My count is off on the website. I think I’m at 753 because I lost some of the early shows. I lost the playlists for a lot of them. I’m off on my counting, but, you know, 752, 780… it’s kind of all the same.

Ron Morelli: There are barely any mix shows with dance music on the FM dial. It’s few and far between. And that’s just throwback stuff, it’s not contemporary.

JD Twitch: When [Beats in Space] very first started, it felt then that the electronic music scene in Europe and America was—there was quite a wide divide there. Not more sophisticated [in Europe], but more ingrained in everyone’s culture. And I think when Tim started Beats in Space, it felt like what he was doing was something quite pioneering. Especially in New York, where there’s a history of great radio, but specifically for the music he was playing—it was a beacon for people, especially over there, people listen all over the world, but in the United States, it helped create something, definitely.

Matt Werth (owner of RVNG Int’l, who co-runs the Beats in Space record label with Tim): [Beats in Space] held a pretty reverent place for me. It was kind of the music that Tim championed on the show and then transitioned into a live capacity, to be DJed, that was really kind of pushing every angle that was interesting to me.

Kim Ann Foxman: I think [the show is] super important. It’s one of the special things that, you know, it’s so on-going, it’s a staple, you know what I mean? If it was ever gone, for some reason, people would freak out. [laughs] People listen to it all around the world, and a lot of DJs look forward to playing the show when they’re in New York—it’s like a New York thing. “Oh, I’m in New York, cool, I’m gonna go play on Beats in Space—or I’m gonna try to, anyway.” So at least in the DJ world, if they get the opportunity to, it’s something that they definitely want to do. It’s like part of the routine… “Okay, I’m going to go to the record store, going to go to A-1, I want to play on Beats in Space, do all these things while I’m in town.” I think it’s definitely a mega-staple.

Prosumer: It’s so great to experience something as unpretentious as Beats in Space. Of course, the show is internationally known and has a lot of followers, but it grew organically, it had been established at the time where all the mechanics were not working as they do now. It’s something genuinely charming to go into the basement of a university into the studio where there’s nothing hip or glamorous. Just to be there and listen to music, talk about music, and it has a very down-to-earth charm. The reason why so many people enjoy doing the show, next to him just being a lovely guy, is that really everyone can relate to this, doing your stuff in a basement. I think that’s how everybody started and how everyone in a way still feels about what they do, being a music nerd in a basement.

Jackie House (a.k.a. Jacob Sperber, co-founder of Honey Soundsystem): It’s in a college. When you go do [the show], it’s really shocking like, “Should I say ‘fuck’ around these kids?” Then you feel super cool because you’re older than them, but you realize how it all creates the energy around the show that you never understand until you go on the show. It’s kind of a fratty experience. It’s not a trippy, sci-fi radio show. It’s very collegial…

I’ve only played the show once in person with Jason [Kendig, fellow Honey Soundsystem resident]. I’ve called into the show when Ryan Smith played and there were lots of call-in things happening. I’ve texted a lot of people while on the show to try to get reactions. I played once, could’ve been better, will be better. It’s great going and realizing just how janky the system is. You’re psyching yourself out for perfection and then you get in there and realize there’s no way it’s going to be perfect. I have so much respect for anyone who goes in there and plays live and it’s perfect. It’s college radio gear. What’s awesome is some of the people on that show with ridiculous artist riders and he’s not doing anything to cater to that. It’s a level playing field almost.

Mike Servito: Doing the show is very nerve-racking. You get on there and Beats in Space is this coveted thing for DJs. It’s the one thing everyone wants to do besides play at Berghain. Getting on Tim’s show is nerve-racking because there’s lots of pressure. You want to do your best. It’s archived, it’s recorded. It’s a one-shot deal, there’s no room for error. There’s a tremendous pressure to represent what you’re doing. It depends on the personality and the person, but for me personally, it’s a lot of “I need this to be representative of me. I can’t slack on this one shot.”

Prosumer: A lot of times, I was inspired by record shopping trips. I remember one time I played a lot of records I found days before in New York. There was one set where half the set was stuff that I found in San Francisco a couple weeks before, at Groove Merchant. I usually have a couple of records in my bag that I won’t end up playing in the club, but if I somehow get there, they can be the big moments. These records end up being played when I’m doing Beats in Space.

JD Twitch: Sometimes, if we can’t make the show, we’ll say we’ll record something, have it for you—but it’s not the same. Having done the show, been there, having banter with Tim, we want to be there. And we have a lot of freedom on the show. One time, Tim knew I liked cumbia music from Colombia, and he said, “Next time you’re on the show, why don’t you just play cumbia records? It would be great to do something completely different.” So it was great to have this opportunity to play music that I never get to play anywhere except my living room.

Josh Cheon: When I had my own show, the Halloween show, it was me playing records for the first bit, then interview, then Tim played records. It was really fun. I did this very atypical set since it was Halloween, so I played a lot of my high school goth records and industrial records. It wasn’t typical, it was more freeform. I liked that I could do that on his show.

Bryan Kasenic: I think between Tim and I, the huge difference between us is—he either didn’t care or he recognized the potential of the internet before anybody else put archives and stuff like that online. It might’ve been way less advanced than it is now, but Beats in Space always put the sets online. He seemed to see the potential of that, which I can’t even remember what year I stopped doing radio, 2005 or something, but I just kind of got sick of sitting in a room alone and feeling like nobody was listening and I think that Tim definitely saw the potential of using the archive on the web and really promoting that. And now, in retrospect, I’m like, “Oh, I should have hung onto that!”

JD Twitch: It was quite pioneering. Then word spread. I would run into kids here [in Glasgow] at our club nights and they’d say, “Have you ever heard this radio show, Beats in Space?” And word spread and spread and now it’s hard to imagine it ever not existing…

The show has a personality. And you know, Tim is famed for his interviewing technique. [laughs] There’s an online music forum called I Love Music, and there’s a thread about Tim Sweeney’s interviewing technique, which is very endearing—he’s not slick. But that’s what makes him so charming.

Prosumer: He reminds me in a way of David Letterman. Tim’s the David Letterman of techno. He’s asking in a laidback way that’s non-obtrusive: “Why don’t you talk about it… tell me something,” but you don’t have to. [laughing]

Justine D.: He’s kind of neat and to the point and asks pretty sincere questions… There’s not a lot of bullshitting on his part and it’s not like he’s pandering to the guests or playing favorites at all.

Tim Sweeney: [chuckles] With the interviews, it’s kind of about connecting somehow with who you have on the show. So trying to find ways to make them and yourself feel the most comfortable together on the radio. And you know, when you have someone on the show who doesn’t really like to talk, [you] figure out how to make that interview quick and painless and just go to the music. And that definitely happens a lot, where you’ll have someone on who just really isn’t good on the microphone, so you just—what’s most important is the music and doing the mix show. And if someone wants to talk the whole show, then they can do that too, but it has to be someone like a DJ Harvey, where they’re super funny and interesting and love to talk. Then it’s easy…

What I remember doing, is when I started my radio show, I started putting it up as RealAudio files. I remember it was before there was any MP3 stuff happening. Once you start getting emails from people all over the world, people in Australia or Japan or Berlin or London or whatever, then you’re like, “What’s going on?” After a couple of years, I started feeling things getting really bigger and bigger. Obviously, when I started touring more, then you go out on the road, people come up to you and say they’ve been listening for years and years, and it kind of blows you away.

Justine D.: Tim had this older gentleman who lives in the outer boroughs. I think in the early days he’d call him every single week. I thought it was so bizarre that this older guy called in. Victor was pretty much harmless, but I think one time Victor became somewhat irate at Tim for some reason. I don’t remember why. I think that’s a great example of the very old-school [radio] experience—someone calling in on the phone to give their opinion. That’s always been one of my favorite things about Beats in Space—will Victor call this week?

Tim Sweeney: I like to hear from the listeners, but I don’t really have a lot of time to do it, so I made the hotline as a way to, you know, hear the listeners. Last time DJ Harvey was on, I had the listeners call up the hotline and then leave messages for him, and then the best ones I would play on the show for him to answer. It’s nice doing that, because it connects the listeners to the show. It’s really fun. In reality, most of the messages are from Victor from Washington Heights. He leaves three or four messages a week. [He] calls in and he hates on anything that’s old, anything disco, anything that’s like—the vocals are in another language. He gets really upset at me. He’s the one that is the most vocal about hating things.

Ron Morelli: [Tim] has Victor now, too. He’s injected a new life into the show. Everyone wants to know what Victor thinks. No one cares what Tim thinks. Everyone wants to know what Victor thinks, you know? Victor called the last time I did the show. And he approved of my set.

Prosumer: We spoke about Victor a lot, but I don’t know if he is approving of my sets or not. If he had approved, Tim would’ve told you.

JD Twitch: [Regarding the cumbia set mentioned previously,] I’m sure Victor from Washington Heights—I’m sure he hated it. For a long time, I was convinced it was something Tim invented. And I thought Juan MacLean was Victor. But now, I’m sure that he is a real guy.

Jackie House: Ken [Woodard, a.k.a. Ken Vulsion] who was on the show, who I started Honey [Soundsystem] with, has a mild obsession with swim culture. Inside joke for us—we make the gayest thing ever, a Speedo with our name on it. Makes everyone uncomfortable. Ken brought Tim a Speedo, asked him what size and brought him one, which started that whole wave of hilarity…

For our second mix on the show, a recorded mix, Ken did that mix. I sent this fake letter [to Tim, addressed] from our friends partially to get our fans to know we would be on the show, to call Tim out, and to do something hilarious. So I was like, alright, let’s create a little buzz around it with this fake letter that said, “Everyone here, all Honey fans, are really excited and request that you wear the Speedo.” The dance music community in this iteration are way more hip to gay jokes. Back then, it was more risque to joke about the gay community. Tim’s got a good sense of humor, but some people might have thought that there were gay people who wished Tim would wear his Speedo on the show.

Kim Ann Foxman: On my second show, I pretended that he had a Speedo on—so I was like, “Oooh, Tim!” He was talking about how the week before, Honey Soundsystem played or something, and he was talking about the Speedo they gave him. So the next week or something like that, I was like, “Oooh Tim, your Speedo looks really good on you.” I have a really fun relationship [with Tim] where I constantly fuck with him. I like to tease him and stuff. We play around. [laughs]

Prosumer: [laughing] Of course we can talk about Tim in his Honey Soundsystem Speedo. Did he actually wear the Speedo? Of course… every episode of Beats in Space, he’s wearing the Speedo.

DFA AND DISCO

Tim Sweeney: I was DJing at this bar in the East Village, it’s closed now, called Plant Bar. Luke from The Rapture was the bartender there. I gave him a mix CD and he hired me to play 7 to 10 p.m., before the party started, and I was totally happy to do it because I was underage and wanting to DJ anywhere in New York. He told me, you got to meet these guys who are producing our next record—I think you’ll really like their stuff. He told me it was Tim Goldsworthy, and then I couldn’t believe… I was a huge fan of U.N.K.L.E., so I knew exactly who he was. He was just totally under the radar of most people. I was so psyched to meet him, I told Luke that whenever Tim comes in, you have to tell me. So a few weeks later, Tim and James [Murphy] were there, and I think Marcus [Shit Robot] as well, so I went up and said hello and just asked if they needed any help in the studio. Tim said, “Yeah sure, come in on Monday.” So I went in and started becoming an assistant to Tim and James in the studio after that.

Justine D.: He started with [DFA] when he was very young, he was probably a freshman or sophomore in college. This was before I had actually met him. Tim started off as an intern but then it morphed into—because Tim knows how to play sax and a bit of piano—he started working on production with Tim Goldsworthy. It morphed into production work with DFA and it went on to whenever DFA needed to do a mix, like a mix for Chanel in 2008, 2009, he was commissioned to work on that. It was more production towards the end of it.

Tim Sweeney: [I started with DFA] right before the record label started—it was DFA Productions, not the record label just yet. It was 2001. I remember going to DFA when the World Trade Center stuff happened and being with the DFA family when that happened. [pause] Yeah.

Josh Cheon: I interned at DFA after Tim left. He was the first DFA intern. I responded to an ad in CMJ. They told me I was the only person to respond. It was right before The Rapture and LCD Soundsystem. It was 2003, they had two 12″s out —Juan MacLean, and [LCD Soundsytem’s] “Losing My Edge” had come out. They told me that they let Tim go… maybe they told me this to scare me, that he would come in and rip their CD collection and not do any work. So they were like, “Don’t do that.” I wasn’t even ripping, I was so into vinyl, I was like, “Who wants your digital files?”

Tim Sweeney: That is called a bad Jonathan Galkin [DFA co-founder] joke.

JD Twitch: One time we were in New York, some guy comes up to us, hands us a white label, [The Rapture’s] “House of Jealous Lovers.” And we got home, and we were like, “This record is phenomenal.” We played it, and played it, and played it. Huge Optimo anthem even before it came out. Then we heard The Rapture were doing our first UK dates, and we were like, we had to have this band come and play. Even then, nobody really know who they were. And the sound guy was James Murphy. He was doing the sound on that tour for them. We instantly hit it off, had an instant rapport. [So, our connection with] Tim was [via] the DFA family, because he had interned with them, and was super great friends and remained so with Tim Goldsworthy, part of DFA. He would hang out in their office all the time. We did a DFA party a little later with Gavin Russom and Delia Gonzalez and Tim was doing a DJ thing—the two Tims, Tim Sweeney and Tim Goldsworthy. Subsequently, Tim must have been to Glasgow, I don’t know, about 20 times. Sure, if you asked him, he would definitely have an affinity with Glasgow, much like we have an affinity with New York.

Matt Werth: DFA was just like this completely inspired record label, really for me, kind of harkening back to a time—the downtown ’80s world of record labels, like the dance crossover record labels. It was kind of authenticating the downtown NY of the early 2000s. Walking into NY then and having this amazingly programmed catalog, a distinguishable label presence, was super, super inspiring. It was such a great alternative to all of the rock posturing at the time. There was this industry ooze around that time that spawned all this really mutated rock and roll.

Kim Ann Foxman: New York had been going through a lull in music, and especially dance music, so DFA were really—after the fall of electroclash, it felt really dead in New York, there’s nowhere to dance, so when DFA came up, it was really strong in New York. “Oh, finally, we can play some dance records.” What’s cool about Tim’s show is that it’s not just all one style of music. It opens people up to different DJs from everywhere, and they bring in sounds that we haven’t heard. Sometimes it’s really weird and chill, and sometimes it’s really dancy. So that’s nice because it’s a really broad range of good DJs that you can listen to, and he has a really open mind.

[What you play] doesn’t have to be the hits. Actually, it’s fun to play [Beats in Space] because you get to play stuff you wouldn’t normally get to play. You can make a story, or a journey out of it, if you want to. If you’re used to playing primetime as a DJ, it’s a lot harder to start out—there’s not too much room, but on the show, you have total freedom to do whatever you want. And [Tim] encourages that.

Mike Servito: I think Tim’s show wasn’t just portraying straight house music or straight techno. All those other outlets that kind of touch base on dance music with DFA and similar groups, formats, labels—I definitely was exposed. Tim’s definitely playing that kind of music. Outside of rave culture and proper house and techno DJs, all those kind of rock kids were paying attention to DFA. There was an element, a kind of edge, that people were honing in on. It all started to kind of blur. 2005, I feel like was an explosion—the whole dance rock thing was happening. DFA was in their prime. I think Beats in Space has maybe shifted since then, but I think at its core, Tim is kind of supporting and exposing the whole entire genre.

Ron Morelli: A good DJ can mix hip-hop to disco to house to techno seamlessly. This is what DJs used to do in clubs. Your job as a DJ is not—these days people think, “I’m a techno DJ,” they play straight techno for three to four hours, “I’m a house DJ, I do this.” But if you’re a DJ, you should be able to play it all.

Matt Werth: Metro Area, at the same time, really honed in on that exact more old-school disco and house flavor versus how The Rapture was post-punk/disco. But I heavily associate that version of disco, Italo disco, cosmic disco, with that [early-mid 2000s] era in New York because all of that was being played alongside The Rapture and LCD. Tim was knowledgable and came from this turntablist background and was able to totally take those elements and as any great DJ does, make them work together so there’s no disparity between the decades.

Josh Cheon: He was definitely pushing, hustling [the DFA sound] on the radio, they were giving him unreleased mixes to play. James Murphy would do a DJ set on his show, and he’d have other acts. A lot of connections were made via DFA for Tim and his guests and people who came through, “Oh I’ll hook up with DFA and do a remix.” I feel like a lot of the remixes were buffered or negotiated or introduced through Tim’s radio show. Tim was out there playing these songs that weren’t even finished or being mastered and that probably helped if he could play it for a crowd and see what the reaction was. Then he could go back to the DFA dudes and be like, “Oh they really liked this song, let’s do a 12″.” I’m sure they really value his opinion.

Tim Sweeney: I remember pretty vividly when I played the Carl Craig remix of Delia & Gavin’s “Relevee” from DFA Records, which is why I put it on the 15th anniversary compilation, because I remember playing that track and it was, you know, before anyone else had it. The guys in DFA gave it to me and they handed it to me and said, “You can play it, but you have to talk over it.” I remember talking over a lot of it. And I remember afterwards, the response, people were pissed that I was talking over it, but they loved the track. And the response was so big, I realized people were really checking this out, you know, because I have this music no one else has, and from then on, I was like, “Okay, this is really getting to a lot of people worldwide.”

Jackie House: The best part about Beats in Space is that you know no matter how dark the show is gonna get, it’s not going to depress you. Tuesday night is a night where you can easily get depressed. The time slot he has is potentially a time you’ll be relaxing or going to bed depending on where you are, trying to cool it. If you’re cooling it too hard and suddenly sad about shit, it kind of sucks. The DFA sound of course was pinnacle to that show creating itself. The DFA sound never gets too dark, it’s just drunken depression, never full-on misery. There’s a long “cowbell period” of Beats in Space and now it’s the “909 snare” period of Beats in Space, ’cause that can go super dark, but it’s just as hard as he’ll let Beats in Space get.

TIM SWEENEY: THE MAN, THE DJ, THE FUTURE

Tim Sweeney: You know, I never know what will happen with WNYU, but I want to keep doing [the show] for as long as I can. I really do love doing it and I can’t… to not have that in my schedule just feels totally wrong to me. I would find a way to keep going with it. And with radio, it’s a nice thing that you can keep doing for a long time. It’s a great thing. The one thing with doing the radio here—I don’t get paid anything for doing the radio show. I am paying for my website, for the server and everything—I’m putting up the money for it. But you know, it’s promotion for me, but it’s all because I love doing it. And one day, you know, maybe getting paid to do a radio show would be pretty cool. [laughs] But I’m not hoping for it.

Justine D.: [Tim] had his first DJ gig when he was 15 or 16, so he’s going on 20 years of DJing. I think he started DJing back in high school…

It’s this innate love of music, that’s what it starts off with. What Tim has been able to do, and this is what makes it so enticing to stay with it, is that he’s reached international notoriety not just as a DJ, but also as a music tastemaker. And not a lot of people have reached that status.

JD Twitch: Tim is actually insane. He will do everything—anything—in his power to be back there in the studio. He plays all over the world, so sometimes he’s going back across the Atlantic. It would make more sense for him to come over [to Europe] for two weeks, but he has the radio show, so he will go back in between, just because he is so dedicated to that radio show. And that’s the thing about longevity. As long as you still have that passion to keep doing it, and want to do this thing, it will never start getting boring.

Ron Morelli: [Beats in Space] is a labor of love, you know? He’s committed to music and he cares about it. And that’s the only reason why you do it. You don’t get paid to do your radio show for 15 years. There are nights, I’m sure, when you don’t want to go to the show and do it. It’s a job. But he loves doing it. It’s his passion, you know, so it’s kind of a no-brainer.

Prosumer: I would say and I hope it’s not a romantic idea that it’s his passion for what he does [that has kept the show going]. You need to be passionate to do what he’s done for such a long time. It probably would not have been like that in the beginning. The first years must have been more like, “Is someone really listening to this?” That is something that you do for yourself, that you don’t do for an audience or for a reason that you could justify to your parents, more for enjoying what you do.

Jay D.: [What makes Tim a good DJ is] his open mind, his knowledge. He plays whatever he wants to dance to. That’s it. DJing is simply what you want to see people dance to. He’s got good taste. I’m a better DJ, you know. [laughs] He’s a stand-up man, you know. A mensch. You don’t have too many people like that in the game. He’s also very generous in the way he has people come to his show. He has them DJ, he DJs a little bit, like he’s sharing the love. There’s no other way to put it. He’s making it happen.

Matt Werth: I think a big part of it is that those experiences give him the chance to meet and delve a bit deeper with people that he finds fascinating, or finds their music fascinating, so therefore it’s at the very core of his sincere love of music. It’s a labor of love. He shows up every single week to record this show or to be in the station because he wants to be there. He’s not clocking in when he flips the on air switch. He truly wants to be there, experiencing the music.

Bryan Kasenic: I used to hear Tim spin from time to time. He would spin at Subtonic where we did The Bunker, but he had a Saturday party and I remember hearing him play at Third Ward back then and he had a pretty—I don’t know how to describe it—an open sound. It’s like, if you’re really into it, you realize how deep he’s digging, but if you have no idea, you’re just kind of on the surface, and if you’re just some girl going to a party to hang out, you can get into it, which is good. [laughs]

Prosumer: I kept joking with him about this—with the new hairdo came the womanizer, after the long hair went and the smart hairdo came around. There was one set in Paris [where I got to] see how flirty how the front row of Parisian ladies were with Tim, and how he in a very shy way was still enjoying it.

JD Twitch: Now, you know, we’re waiting for Tim’s music producing. Every time I see him, I’ll go, “So, Tim…,” and you know, he’s done edits, but he’s not ready to produce yet. I think it’ll happen. How old is Tim now? I always think of him as being, like, 18—he’s permanently that age in my head—but he’s what, mid 30s? I can’t imagine Tim’s going to give it all up and become an accountant any time soon. I think he’s in this for the long haul.

Justine D.: I always wanted to see him produce more. Tim has always had the urge to and even when he has produced things, he did really beautiful pieces of work. Unfortunately, we aren’t able to hear too many of them. But we’ve all been waiting for a long time. So maybe he’ll finally do it.

Matt Werth: Tim had always the idea of a record label and I think he may have announced it quite early on without it actually having matured or been materialized. I think it hadn’t totally taken form. I was just like, “Wow, that’s cool, I can’t wait for the Beats in Space label.” And I would tell Tim that. Everyone else would tell Tim that. Like, “Wow, when is this gonna pick up? When are these releases that you mentioned going to be out?” Eventually, I think a part of me kind of prompting him… we have this proven record, relationship via the RVNG mix series and I had supported him along the way, introducing him to our designer who commandeered all the RVNG artwork and helped me make t-shirts and stuff like that. It was like a coupling of me asking what’s happening and him in turn being like, “This is a good place for Beats in Space to be.” So we started the record label and it’s been excellent.

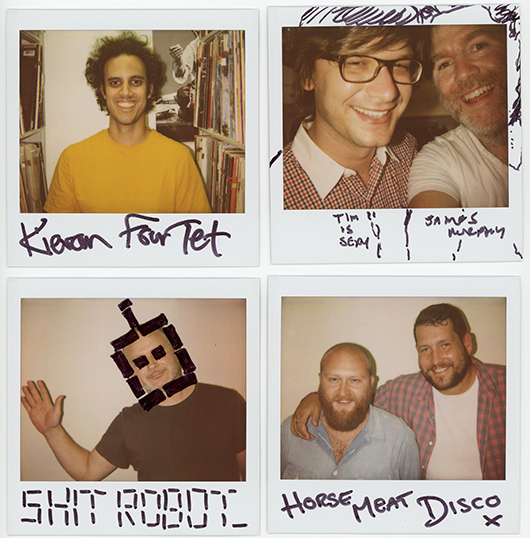

Mike Servito: It would be great to see a Beats in Space book—just a polaroid book. I’m sure it’s in his plans. He doesn’t miss a beat—no pun intended. He really thinks it through with his label, too. His label is exciting. That alone—seeing someone put that much effort into the sleeves alone—that’s a dying art form. He cares so much about the packaging and what it looks like.

Jay D.: He puts a lot of effort into having a nice cover, nice artwork. It’s not just a white test pressing. Putting out a record now is expensive. There are less pressing plants and they’re backed up with orders. He makes an effort to put out some cool stuff that sounds good and is visually stimulating with the cover. Institutions happen because of hard work, labor, and ethics, which is the same in the vinyl world.

Tim Sweeney: Yeah, I want to keep making the record label, keep growing with the record label. Keep building that. Definitely keep up with the radio show, and do a lot more Beats in Space parties around the world. I love curating nights which I’ve done—I did Panorama Bar [recently], did a Beats in Space night. It was amazing. Panorama Bar is amazing. The week before, I did a Beats in Space night at Corsica Studios. It was really fun. It’s really nice to have these guests I have on the radio show, to have a party with them.

‘Beats in Space 15th Anniversary Mix by Tim Sweeney,’ out now on Beats in Space