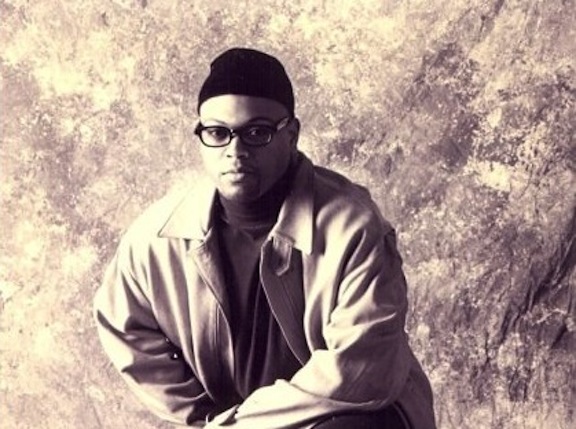

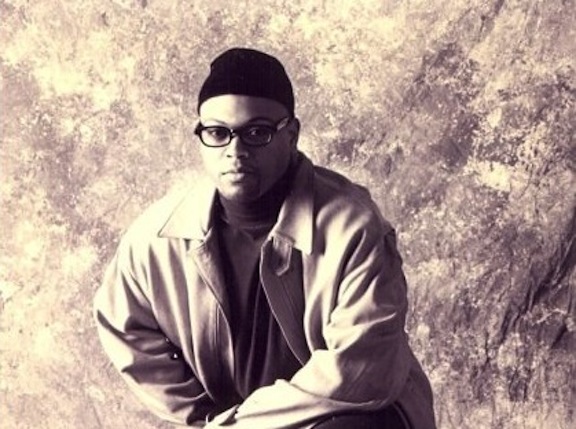

Get Familiar: Vincent Floyd

A Chicago house stalwart gets the recognition he deserves.

Get Familiar: Vincent Floyd

A Chicago house stalwart gets the recognition he deserves.

Vincent Floyd and Armando Gallop were just teenagers when house music exploded in Chicago in the mid-1980s. As childhood friends who grew up across the street from one another on Chicago’s southwest side, they attended and threw their first parties together and shared what they’d learned about producing music, as well as keyboards and drum machines. Each released records on hallowed record labels like Trax Records or Dance Mania, and both have discographies studded with records now considered to be Chicago house classics.

But where the late Armando is remembered as a foundational figure in the genre’s history, Floyd is seen as more of a footnote, except to dedicated collectors. The most influential of these is Antal Heitlager, head of powerhouse Dutch label Rush Hour, who met with Floyd in 2013 and set in motion an ambitious reissue campaign that includes an entire album’s worth of previously unreleased material called Moonlight Fantasy. One wonders, why is Floyd receiving acclaim only now? And how did two artists who were so closely linked end up on completely different career arcs?

Floyd was born and raised in Brainerd, a middle class neighborhood just west of the I-94E highway that divides Chicago’s east and west sides. Surrounded by records at home and growing up around uncles who were professional musicians, he followed in their footsteps by learning the piano and guitar while obsessively listening to the radio his grandmother bought him. A fervent fan of the Beatles, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson, and Prince, he applied his talents to a slew of basement bands that spanned rock and soul.

Disco was still the dance sound of Chicago in the early 80s, even as it was giving birth to proto-house. Floyd first heard this new hybrid sound at Loop Roller Rink on 95th Street, tagging along as a then 14-year-old Armando Gallop made his DJing debut. Enthralled but lacking the necessary tools, it would be a few more years before Gallop and Floyd would try their hand at making house music.

Gallop was first to invest, buying Roland’s 303 and 707 drum machines and learning to use them along with Chris “Bam Bam” Westbrook and other neighborhood kids. In 1987, he made his debut with “Land Of Confusion,” a seminal acid house record that garnered a great deal of attention from Chicago’s DJs and dancers. Floyd, meanwhile, had begun making house music as well on a low key basis, but was more involved as a guitar player, both in bands and as a session musician at Blueheart Studios and Hairbear. He also studied sound design at Columbia University Chicago.

“[Armando] used to say to me, ‘Man, you’re just doing this for yourself. You’re just doing it for you!’”

It wasn’t until 1990, at Gallop’s behest, that Floyd considered showing his house tracks to record labels. “[Armando] used to say to me, ‘Man, you’re just doing this for yourself. You’re just doing it for you!’” Floyd says with a chuckle. Gallop had racked up a handful of hit records by then, his latest being a Dance Mania EP introducing the world to Robert Armani, another Chicago producer. When he connected Floyd with Ray Barney, the proprietor of Dance Mania, the latter snapped up a handful of tracks that would become his long awaited debut.

That record, “Your Eyes,” left no doubts about Floyd’s talent as a writer or his production prowess. While many of his peers, including Gallop, were releasing banging, utilitarian tracks shot through with acid, Floyd’s sound was largely serene and thoroughly musical. “Your Eyes,” which features the impassioned vocals of Chan, takes cues from musical heroes like Prince and nods to Floyd’s contemporaries in Fingers Inc. There’s innovation at the same time, helping lay the foundation for decades of deep house with rolling hand drums, tasteful guitar licks, and gauzy melodic swells washed away by samples of waves crashing.

Floyd would explore this specific vein further on “Cruising (Long Ride),” released on Resound Records, the label he started through a P&D agreement with Gherkin Records. Inspired by long drives up Lake Shore Drive, the street that runs along Lake Michigan for almost the entirety of Chicago, the 12 minute long track is hypnotic and mellow, wrapped in dreamy pads and laced with whirling pitches and heavenly leads. The flip side, “Isolation,” is predictably even more placid. Yet it’s the only release Resound Records ever had. Even Dance Mania only got one more record out of him in 1991, the treasured “I Dream You.” It would be another four years before Floyd’s next release.

“I believed people thought I sucked. I never got any feedback [on my music] whatsoever. It was never played. I never heard it.”

Unlike the present, when the feedback loop between artists and audiences has become so short, getting feedback on your work was once rather difficult unless you had particularly high profile. “Back then, I believed people thought I sucked,” Floyd admits. “I never got any feedback [on my music] whatsoever. It was never played. I never heard it. A few times WBMX would play “Cruising,” but I just figured it didn’t do anything.”

His perceived lack of success was reinforced by his relationships with record labels, which offered no indication of how well his records sold. It just didn’t seem like there were many reasons to release more music. “I’m perfectly cool with having all of my bad stuff to myself, but having my bad stuff out there– it’s like your child. If your child acts a fool in the house, you’re a lot less affected by it than if they’re out in public, letting everyone see them act a fool. So I kept it to myself.”

Despite this, Floyd was musically active the entire time. He recorded guitars and keyboards for many artists on Rockin’ Records and others, like Candy J. He continued DJing and promoting parties he and Gallop threw on Chicago’s south side. He even went on tour as a keyboardist for Larry Heard in 1992, when Mr. Fingers was on MCA Records. And between recording at home and at the studios where he worked, Floyd kept amassing unreleased tracks. Some eventually found their way onto EPs for Cajmere’s Relief Records in 1995 and Rated X Records and Subwoofer in 1996, most of it harder, faster, and less nuanced than his earlier records.

That same year, Gallop was diagnosed with leukemia. Floyd was by his side at the hospital nearly every day. “We figured everything would be ok, because when you’re young, death is the furthest thing from your mind,” Floyd remembers. “Even when it’s the bleakest situation ever, you’re optimistic that it will be better. But it wasn’t better.” On December 17th, 1996, Gallop passed away at age 26. Coping the death of his best friend during a typically brutal Chicago winter, Floyd looked for an escape. He and a friend packed their belongings and moved to San Fernando Valley, California.

There he rejoined the music industry, but not as a dance music producer. Floyd revisited his instrumentalist roots, performing in alternative rock bands, jazz combos, and producing the occasional R&B instrumental. But the music industry in California was even more voracious than the one he’d left in Chicago, offering few chances to move up in the ranks or be compensated for hard work. Floyd returned to Chicago in 2000 shortly after the turn of the millennium, using his musical education to teach music to young kids in Chicago public schools

“Do what your calling is, because all of that extra stuff… the years go by very, very quickly. Wake up, go to work, go home, sleep, repeat.”

When I met Floyd in Hyde Park on Chicago’s south side, he didn’t seem particularly enthused about his current career. While discussing jobs he urged, “Do what your calling is, because all of that extra stuff… the years go by very, very quickly. Wake up, go to work, go home, sleep, repeat.” But the smile returned to his face and excitement entered his deep, animated voice when the conversation turned to his music. Thanks to Facebook, Floyd is now well aware of how highly coveted his early records are, and is in regular contact with fans. “I get messages every day from people from places like Africa, Ireland, Germany, Spain, the U.K,” he attests, “I had no idea anything ever sold anywhere.”

The Internet also connected him with Antal from Rush Hour, who suggested reissuing “Your Eyes”. Antal then began combing through hundreds of songs Floyd recorded between 1991-1995, many made for an sci-fi themed album that was never released despite the promises of a handful of labels. “When stuff isn’t going through, I don’t chase people around,” Floyd says. These finally see the light of day on the recently released Moonlight Fantasy album, containing cuts like “Dark Matter,” “Dawn Notes,” and “Imaginary Voyage” that are unwitting predecessors to the deep house aesthetics now commonly found on records by Move D, Jack J and the Mood Hut collective, and many more. A reissue of “I Dream You” is in the works, as well.

Now more confident in his artistry, Floyd is eager to put his music into the world. He’s been fielding offers for previously unreleased material, both new and old. A few months ago he visited a nightclub for the first time in years and plans to return at least once a month. “I think you just have to, even if it’s just to hear music on some real speakers,” he notes. “You can certainly become lost if you don’t go out.” And he’s getting back into DJing with hopes of returning to the decks of Chicago’s clubs someday soon.

Imagine if Floyd had received just some of the recognition and praise pouring in now when he was first releasing records—the underground mystique surrounding his first three records would be likely replaced with a general sense of reverence towards an indispensable figure in Chicago house history, kind of like his friend Armando. But now the dance music world is more aware of this tremendous artist than ever, and can start making up for lost time and admiration.