Q&A: Matrixxman

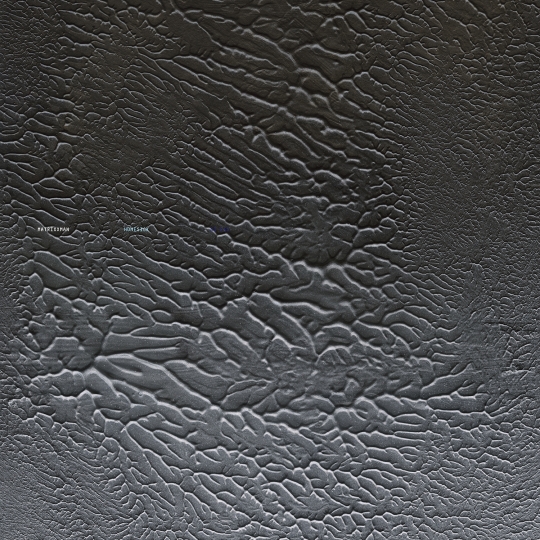

The philosophically-inclined producer prepares to release his debut LP, 'Homesick,' on Ghostly International.

Q&A: Matrixxman

The philosophically-inclined producer prepares to release his debut LP, 'Homesick,' on Ghostly International.

Just over a year ago, Matrixxman delivered a mix to XLR8R for our podcast series—and what a glorious mix it was, reeling us in with such seminal cuts as “Optimo” from NYC dub-funk combo Liquid Liquid, the Italo-tinged synth oddball “Hot on The Heels of Love” by the art-industrial overlords of Throbbing Gristle and the stripped-down disco glory of the Trammps “Whatever Happened to the Music” via that track’s great Paul Simpson dub, before settling down to alternate between beautiful deep house, jack-worthy techno and the like. (Check that podcast out here.) “With that set,” the man born Charles McCloud Duff says, “I felt it was important to lay out my influences as a producer, with all those disparate themes within the mix.”

At the time, that decision made total sense. Though Matrixxman was certainly not new to the production game—he had worked in the early days of this decade with then-partner Paavo “Earthman” Steinkamp under the 5kinandbone5 moniker, following that up with work on Classicworks, Discobelle, Soo Wavey (the label he ran with Vin Sol) and Ghostly International imprint Spectral Sound, among others. Still, he was something of an unknown quantity, and that kind of introduction to the world was in order. But now, Matrixxman is far beyond the introductory stage of his career: Ever since that mix, the producer’s been on fire, largely via a string of great releases that have seen him refine his sound; it’s been distilled to a style that fuses the dystopian feel of sci-fi electro and Detroit techno to the joyful jackability of Chicago house, laced with a charming wide-eyed innocence that emanates from Duff himself. He’s capped off that run with Homesick, a fantastic new long-player coming out on Ghostly on July 10—and having heard the album, we can safely predict that Matrixxman will not be fading into the digital ether anytime soon. XLR8R recently caught up with the Bay Area artist for a brief, freewheeling chat—and here are are the results of that conversation.

People originally became familiar with the Matrixxman name through your work 5kinandbone5. Had you been making music before that?

I had been doing stuff here and there, fooling around–but nothing really seemed to really gel until the past five years. That was around when I started working with people who mattered. Music still wasn’t a full-fledged career for me, though I making progress towards that.

So it’s safe to say that things really started to come together around the formation of 5kinandbone5.

I would say so. 5kinandbone5 was a duo with my best friend Paavo Steinkamp, who’s doing some really good techno on his own now—I’m really happy he’s reentered the picture. Our interests were really diverse; we were both raised on hip-hop and drum & bass, and both had an affinity for proper dance music as well. We’re both capable of producing a wide variety of music, so we were having a field day making whatever the hell we wanted, without regard to genre.

Sort of like that podcast you did for us last year?

Yes, and I’ll still play the odd Italo or industrial record—in general, though, I’ve been leaning increasingly more techno and increasingly less house as time goes on. But there is one thing you can take away from that set that I still try to do, to the best of my abilities: I still try to traverse a wide variety of terrain. My pet peeve in live is a DJ that plays a set that comes off as one long, anonymous blur. I’m looking for peaks and valleys; I’m looking for frenetic mayhem.

That actually describes the feel of the new album. Even though you’ve narrowed your sound down a bit, there still seems to be quite a bit of diversity, with elements of house, acid, Detroit techno and lots more in there.

Well, I still think that it’s fun to not limit oneself too much.

Why did you start working solo in the first place?

Paavo’s life obligations were taking over, and even when 5kinandbone5 was still going, I was doing a lot of the 5kinandbone5 stuff myself. There’s certainly no malice or bad blood, but it made sense to do what I was already doing and replicate it by myself. I wanted to be able to see something through from start to finish by myself, and for that to have some kind of impact. I just wanted to do something.

On a very prosaic level, why did you originally choose the name Matrixxman?

Actually, I would say that question is very far from prosaic! It started out initially as a Max Headroom–inspired persona—a character who had gotten trapped inside the network. It was very much tongue-in-cheek—however, over the years, it’s taken on a life of its own. It’s touched on something deeper. I consider myself a futurist, and a proponent of the transhuminist movement, so the name references the role that technology will play in the next evolutionary steps of humanity.

You’re right—it’s not so prosaic. What kind of steps?

Thinks like uploading one’s consciousness, for instance, or the myriad of interesting things that will ensue when the technological singularity shit hits the fan, as it were. [laughs]

“The notion that people will be digitizing one’s self and living sans physicality is quite frightening to humanity, by and large. But I personally think that it’s the most exciting shit ever.”

You welcome that shit hitting the fan, correct?

Oh, yeah. I mean, I get that it’s inherently scary to people. The notion that people will be digitizing one’s self and living sans physicality is quite frightening to humanity, by and large. But I personally think that it’s the most exciting shit ever.

Does all this inform the music that you make as Matrixxman?

It colors it immensely. It’s driving the underlying emotional fabric of my compositions. I’m dealing with machines, and attempting to inject those lifeless machines with some life. If I could make them sentient, I would, but that’s far off the realm of possibility for me at this point. Some people use the word mechanistic to describe it, but I prefer the word machinistic. It refers to our existential relationship with machines. The whole dichotomy of being separate from machines, yet unified, is something that I’m attempting to explore.

It sounds like you are looking forward to the day when you can merge with whatever kind of future machines will be used in the music-making process.

Definitely. I’m sure there will be a plethora of crazy-ass devices that will be able to do things like transcribe note-for-note notations based on your thoughts. It will be so cool.

Speaking of machinery, did I read somewhere that Joey Beltram’s “Forklift” was the first 12-inch single that you ever bought?

That does sound about right. He was calling himself JB3 for that, I think.

You can hear vague echoes of that record, and some of the similar tough, almost industrial techno coming out in the early ’90s, in your work.

It’s extremely flattering that you would mention Joey Beltram and me in the same breath. That era of Joey Beltram stuff is exemplary—it’s quintessential music. What I do is definitely highly informed by that era of techno.

Your music has a futuristic feel, but it also harkens back to classic tropes of the past as well; there 303s, 808s, old-school electro rhythms and whatnot throughout the album. Are you using those kinds of things to signify a sort of retro-futurism, or simply a love of analog sounds, or is it something else?

Well, there are times that I have tried to stay away from drum machines to make music that was a little more digital sounding, but for the most part, I’m drawn to those things. I’m drawn to music with a dystopian edge, juxtaposed with something a little more modern and maybe a little more optimistic. That kind of music can be so beautiful. And if my own music didn’t have that sort of juxtaposition, I don’t think it would be quite as dynamic.

So making forward-thinking tracks with retro sounds and equipment isn’t a contradiction for you?

I can see how it might be a kind of ass-backward approach [laughs], attempting to make futuristic music using machines from the ’80s. But I do find something endearing about the whole process.

Endearing is a good word for it. The dichotomy lends the music a very emotive edge, particularly for people who have grown up on those sounds, or at least have been hearing them for a while.

Yeah, there’s definitely a sentiment of familiarity involved. It taps into archetypes that are ingrained in us.

It’s almost a clubland version of Joseph Campbell’s mythic narratives or something.

We could invoke some Jungian philosophy, but that would probably bore the hell out of your readers.

“You could say that the intent has been there for a long time, but now the floodgates have opened.”

This is your first full-length album, but you’ve been going full-speed lately on the production front, particularly over the past year or so, and your star certainly is on the ascent. Does it feel that way to you?

From my point of view, it seems like this all has taken an inordinate amount of time from when I made my first forays into producing, from the initial desire to make a contribution to the scene to today. You could say that the intent has been there for a long time, but now the floodgates have opened. I mean, it was ’98 when I got my first synth and sampler. Granted, I wasn’t able to really actualize my desires back then, but there certainly was an intense desire to do so. So what’s that…17 years of psychic energy?

And now that energy is coming full circle in a way.

Definitely. But I had to find the ability to focus, and once I did, it was a cathartic experience. When people look at my output rate lately and ask me what’s up with that, I say “Nothing much—I’m just making fucking music!” There’s actually a bit of a bottleneck; I’ve been holding back on releasing some of my stuff.

But with the album, you’re able to release 12 songs at once. That must help to loosen up the bottleneck a bit.

You would think so, but not really. I actually had well over two and a half hours of finished material for the album, and I think that what I didn’t use is as compelling as what made it on to the album.

You could have worse problems. Speaking of Ghostly, how did you originally hook up with the Ghostly-Spectral crew? It really seems like a good fit.

Ghostly is the shit. Sam [Valenti IV, the head of Ghostly] is the truth. He had gotten wind of The XX Files, which was doing some damage on the scene; “Protocol” is still getting played at Berghain, which is a real honor. It didn’t even dawn on me that I had made an underground hit until well after the fact. Anyway, it got into Sam’s hands, we started chatting, and before you know it, I was sending him music. Ghostly is a great home, and its Detroit-area lineage is invaluable.

For the kind of music you’re making, it definitely makes sense to be associated with Detroit, even obliquely.

It’s a dream come true. You know, I never believed in my most optimistic thoughts that things would pan out like this. I couldn’t think of a more optimal scenario.

It’s good that you have a backlog of tracks. Looking at your gigging schedule, it seems like your dates will keep you plenty busy over the next few months.

Yes, that is fortunate. Berghain, Dekmantel, Melt! Festival…the scale of the dates has increased exponentially, just from last year. And last year was an exponential increase from last year.

Does the fact that you’ll be playing for huge crowds at some of these dates make you nervous at all?

One would be lying if they said there was no trepidation involved. It’s an unknown; it’s a new experience. That being said, I feel fortunate that I’ve carved out a bit of a niche for myself. It’s rare that I have to subjugate my desires when I play—and that’s a great feeling.