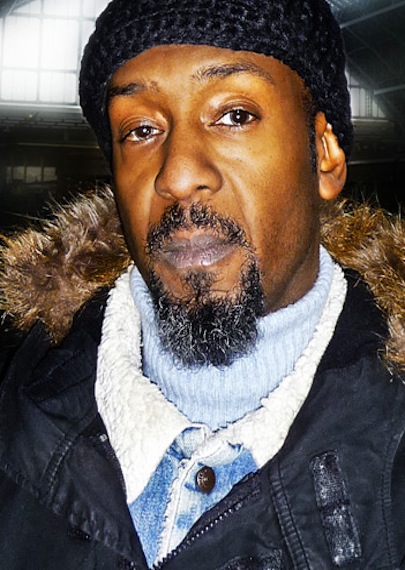

Q&A: Mr. G

With a background split between sound-system bass and techno rhythms. the veteran producer releases a new album.

Q&A: Mr. G

With a background split between sound-system bass and techno rhythms. the veteran producer releases a new album.

Longevity, consistency, and quality don’t always go hand-in-hand—but for the U.K.’s Colin McBean, that seemingly comes effortlessly. His career dates back to the early ’90s; among other claims to fame, he was the partner of Cisco Ferreira in the British techno outfit the Advent. Working solo for the past decade and a half, mostly under the Mr. G moniker, his signature style—cultivated over 60 releases—has generally been categorized as tech-house. But his new album, Night on the Town? (just released on his own Phoenix G label, also available on DVD with an accompanying video), has a much deeper, left-of center sound. His extensive knowledge of American, British, and Jamaican music is combined with a quick-talking and tangential personality, one that’s wholly apparent on his new record.

The city of London is one of the central themes on the album. Can you talk about your relationship to the city?

The album the sound of my perfect night out, that grainy mechanicalness of London. Some of the tracks are hypnotic, some passive, some active, some deep and twisted. It’s all those things happen in nightclubs in and around London. And it’s also an amalgamation of all my influences, whether it’s house, or soul, or techno, or whatever I’m listening to. It’s that musical backbone combined with my love of the city.

Growing up as a small-town Derby boy, I could come down to London for the art, the clothes, sneakers, records…you name it. I’ve seen it all. I walk the same route as I did when I was a kid, I look at the same things. I see buildings and popular art places come and go, new art and new photography spring up. By now I know most of the people in Soho in someway or another, and I love all that. But as I was getting older, I wanted some calm. The madness of the ambulance going by at three in the morning—I don’t want that anymore. I don’t want to hear people coming in from the pub making noise. And that’s a choice a choice you have to make, and I think that’s a choice you make when you get older. I love music, I love sound, I love people, but I also love quiet. Hence my decision to move to the country.

But I still have the ability to get on the train, get off and switch into London mode, running around, talking. And then you get back on your train, and you get your quiet.

Can you talk about Derby, the town where you grew up? What were your musical influences in those early years?

I grew up in a really old-fashioned Midlands town, but it had a strong cultural background—a really robust Jamaican community. So you had parties in church halls, or you’d have the local DJ playing in the community center, so there were always great DJs long before me. We had knowledge of the music, because we were given that knowledge as kids from the elders. So what we used to do is save our money for a month, get on the train and head to London to buy records.

But then you come back to Derby, and you’re DJing in the clubs, and at some point you’re like, this isn’t enough for me. Because you can’t play your amazing rare disco gem to your local people. They’re not ready for that. So when you come through, or chose to come through, you’ve got all the knowledge you’ve been given—but then you realize, oh shit, I’m in Derby. How am I gonna get access to the great music, the great second-hand shops and great charity shops that have all these rare records waiting for me? So eventually I decided to leave, got a job in London, and I spent my days scouring every second-hand record shop.

Can you talk about that Jamaican cultural influence you got from Derby?

My mom and dad are from Jamaica, and I speak patois. I’ve been going to the island since I was about eight. When I go to where my parents are from, every Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday there’s a sound system. So it’s a trip filled with sound. The cars have sound systems, and you can hear them coming from seven of eight miles away. And you can hear that bass rolling, and then rattling the house. So that’s me stocking up on basslines and juice and energy for my next music.

“What I’ve come out of is that U.K. reggae bass that’s always been distinct to the U.K. That bad-boy bassline, I’m in all day.”

Whether it’s Burning Spear, Bob Marley, Studio One, or King Tubby, that bass and analog is in our heritage, and that’s what Jamaica is so important for. What I’ve come out of is that U.K. reggae base that’s always been distinct to the U.K. That bad-boy bassline, I’m in all day. Whether it’s drum & bass, dubstep, garage, that dub is a part of our heritage. And Americans can’t do that bass the way we can. It’s not a part of their heritage. And in the same way, we in the U.K. and Europe don’t have the ability to have that level of emotion—that deep, black emotion that is special to America. Guys like Fred P, Theo Parrish, Moodymann, Masters at Work, Frankie Feliciano, Lil Louis, Joey Anderson…we can’t get that level of emotion on our side. Because our forefathers and backgrounds are different.

So there’s always something to be gleamed in Jamaica, whether you find a new album, a rare record you never heard, or you hear something on the TV, or a car goes passing with the radio. But it really is a tough trip—it’s not a trip for the faint of heart. Jamaica is a tough tonic. So as much as I love going, I’m always slightly nervous. You have to respect what you are, and who you are.

Those Americans that you mentioned, their styles were influenced in some degree by new wave, which was emerging around Derby and the Midlands when you were growing up there. What was your encounterwith those sounds like?

To be fair, I only picked up on that later on in life. Because at the time that all came out, I was a box boy for a sound system, so my life became speaker boxes and late night parties, packing it away and hopefully getting some rum and hearing some great music. There are parts of life that I completely missed because I was wrapped up in the world I was in. But I do remember a club in Derby we used to play called the Blue Note, and we had all of those weird and wonderful groups on Tuesday or Wednesday nights playing, and I would hear them. There are lots of crazy names I remember, but I never thought of it as a specific movement, because the clubs I DJed at played really eclectic mixes of music. That went from left to right without stopping in the middle. So when you talk about new wave, or you talk about punk, or you talk about indie…for me it was also a part of where I was working, where I was DJing, the clubs I played at. Certainly the Blue Note was one of the landmarks in the Midlands for bringing out the unknown left-of-center talent. But it was never about a certain style. It never has been.

Over the course of your career, you’ve released over 60 EPs and singles, but not too many full length LPs. Can you talk about that consistent output, and why you decided this should be a full length album?

I’m a ’70s child all day long. When you do an album project, it should be something that you made pretty much around the same time; you only work on that project for a long time. So normally the 12s and the EPs are tracks that might be from last year, the year before, this year, yesterday. But when something is done over a limited period of time, I think, well that’s an album—because that’s a picture, a snapshot of where you were just then.

Some kids are like, man, how do you put out so many records? I don’t see it like that. I say, I’m a music guy, I live to make music, and hear music. If I make it in five hours or I make it in five weeks, I just keep making music. I might write ten or so tracks over a period of time, but then I have to sit down, and sit with my system and listen back to them and pick out which ones I like. So you end up with this bank of music, and you think, well, it’s no good sitting around waiting. Someone might like that, someone might not like that, so just put it out. What sticks, sticks.

So if you’re an artist, and it’s in you, you don’t just release one here, and release one there. You don’t go like that. I might not have anything to say next year. So I get them out. Let people hear where you’re at. If people like it, if they dislike it—get it out there. I’m a firm believer in that. it’s not a competition thing—it’s just, for me, a way of life.

There’s an introspective quality to the new record. Is that something you intended, or is it something that comes with getting older?

I think that’s the environment. Living out in the country, near water, in a quieter old house. Your vibe becomes introspective. I’ll think about the room where I have my studio, and wonder what happened in that room as years went by. You wonder what goes on. All those thoughts, the greenery around you, walking the dog every day…I didn’t have that in London. It feels slightly freer, you just have the room to stop, go outside, get some fresh air, walk the dog, get some nature, talk to someone, say good morning, good afternoon, good-day. It brings out something different in you.

Your last full-length album came as a result of your father passing. Was there a similar catalyst or this record?

With my father’s album, Personal Momentz, I didn’t know what was in me. And then to hear what comes out, and the message you’ve got inside you, is sometimes surprising. All the experience, all the pain, all the newness went into that album. It felt fitting that the experiences of death, and all the pain, and moving outside of London for a change, culminated in something so positive. It means you’ve made the right choice.

And it’s the same thing with the new one—it’s like wow, that’s what’s in there? Shit. This record is a very different side of me, and I’m quite shocked to see that myself. Obviously you know your work, you do what you do, you know your trademarks, and you know the sound of yourself. Sometimes you have to surprise.

“All those years of working for labels and doing remixes for people you didn’t want to do, or maybe shouldn’t have done—all that makes you very clear at one point when you get older. You’re like, right—this is who I am. This is what I want to be. This is how I want to do it”

Was it therapeutic to come out with a record that didn’t have that weight to it?

Yeah, of course—it was therapeutic, because it’s the knowledge that you’re free. This album was just me trying to do something different. And that’s always been my ethos: I’ve tried to do the best I can with the palette that I’ve got. But there’s a massive freedom, because I feel relaxed and I feel confident about what I’ve done—learning more about my art, I understand now there’s something different going on. And this album…I showed it to a few nearest and dearest, and they were like, “Damn, this is left-of-center, Colin, but I loved it. I could hear you in there, but it’s a different you.” So that makes me feel great. It’s all those years of working for labels and doing remixes for people you didn’t want to do, or maybe shouldn’t have done—all that makes you very clear at one point when you get older. You’re like, right—this is who I am. This is what I want to be. This is how I want to do it.” And also, once you see the video aspect, you’ll understand the extra dimension to it.

Can you talk about the video aspect to it?

There was a real visual component to all the tracks, and so it felt fitting to do some sort of visual accompaniment. I started reaching out to friends, and found out that one of my friends has a sister who is a filmmaker. And we went back and forth on it and I sweet-talked her into it, but it turned out fantastic.

For me to do the video aspect, it’s a massive step. I like to be the guy who goes to the club and does what he does. I want to be there listening to a DJ, or be at home making music. That’s it. I don’t really do the interactive side. It’s stressful for me because it’s not music—it’s not what I’ve been doing all this time. If it were about me performing or me DJing, I’d be like yeah, whatever, I’m good with that. With this whole visual thing, it’s out of my control. So it’ll be fascinating for me to release it, let people see it, and find out what others think. It takes it to a level I’ve never been to before, and that means I’m moving forward. It means I am building, I am trying. It’s so easy in this world to say, “Yeah, I’m doing okay” and be fine with where you’ve been. It’s not about that. For me, it’s about always trying to be a leader, rather than a follower. Give the kids something to look to.