Q&A: Pole

One of electronic dub's leading lights releases his first album in eight years.

Q&A: Pole

One of electronic dub's leading lights releases his first album in eight years.

Scheduled for an late-afternoon phone interview with Stefan Betke, the veteran creator of rustling, rippling electronic dub better known as Pole, XLR8R is having trouble getting through. The call keeps going straight to the voicemail of his in-demand day-job endeavor, Scape Mastering. When we finally do connect, Betke’s in a jovial mode: “Ah, the famous German Telekom!” he says with feigned exasperation, before bursting out in a laugh. “Sorry about that.” He then holds forth on the virtues of old-fashioned analog phones versus newfangled digital communication—which, in a way, is an apt place to start with Betke, as the aural world he creates has both one foot in the past, and the other in the here-and-now. His dub-heavy, highly textured music, deliberately paced and full of stretched sinew, hint at ancient, arcane rituals; his flair for sound design and penchant for gentle abstraction, however, give his tracks a thoroughly modern edge. (Elements of that sound design, perhaps, also speak to an ambivalent relationship with modern technology: Famously taking his pseudonym from a busted Waldorf 4-Pole filter, there’s plenty of frazzled-out crackle inherent in his music.) Betke’s just put out Wald, his first full album since 2007’s Steingarten—and it’s perhaps his most intimate and contemplative work yet. Featuring three reworked in-studio mixes of cuts previously released on his Waldgeschichten series of EP and a sextet of new tracks, Wald‘s a peaceful and warm collection of song—it’s a welcoming, beguiling record, despite that crackle and the occasional shard of distortion. It’s also a plain old great sounding set, proof of his years spent toiling in the mastering business.

Though you’ve been releasing EPs on an occasional basis, is is your first full album in eight years. Why did it take so long for Wald to appear?

There is no real reason for that. Between Steingarten and now, we closed down the ~scape label, which actually was a big amount of work—and also in the few years after Steingarten, I was doing a lot of live shows and traveling a lot. When I finally found time to record new music, I didn’t really like what I was composing; it was in the same vein as Steingarten was, and I didn’t feel like it was bringing anything new to my music. I realized that if I just repeat myself, then it’s not really worth doing. It took me quite a while to figure out what I have to throw out of my vocabulary, and what I can bring into it. I had to figure out my next step, and figure out where I wanted to end up. I wanted to somehow continue my development, without losing the history. And it took quite a while before I found the answer to that.

It must be difficult process when you have such a distinctive sound, to discover a way to avoid repeating yourself without losing the core of your music. And Wald does sound like Pole, though arguably a warmer and more inviting version of Pole.

I would totally agree.

The press release for Wald states the production of the album was proceeded by a series of long walks in the woods. Do you think the inspiration you got from those walks might account for the album’s soothing feel?

Well, not from a mystical point of view. I wasn’t in the forest finding little witches and dwarves or whatever, with them telling me what to do. [laughs] It’s more like an image for me. The forest—the architectural structure of it—gives me the opportunity to remember the sounds that I hear. It’s the same as what can happen in big streets in New York or Berlin. I can remember a sound if I take a photo of that structure when I hear that sound; I can look at that photo in the studio and remember what it was like, what I heard.

“The production allows for a little bit more space between things; it allows distortion; and it feels a little less clean.”

The reason why it might sound warmer is that—even though it’s still very clean and precise—when you compare it to the Steingarten album, I think it’s perhaps a little bit less sound-designed. The production allows for a little bit more space between things; it allows distortion; and it feels a little less clean. I left more of the midrange frequencies in there, and I played the chords a bit lower than I usually do. Usually, I’ll use a C1 or C2, and here we are with a C0 or something. Everything is pushed more toward the low-end frequencies, and that naturally makes it warmer.

Do you think that’s the feature that might differentiate Wald your previous work?

Everything else follows the same idea as usual—how I put it together, the dub influence, the mastering and everything. But I added this element of more bass, more warmth, more guitar-type distortion.

There are guitars in there?

I call it guitar, but it’s not guitar—its synthesizers modified in the computer. And that’s inspired by a lot of things. I listen to Dr. John records a lot, for instance, or Keith Hudson’s early stuff. They all use guitar distortion in a certain way, and even when you listen to music nowadays—like Ben Frost or Tim Hecker—that same thing is there. But I hope that the way that I use it disconnects it from its influences. I wanted something that would be a reminder of those elements, but so disconnected that it’s its own thing.

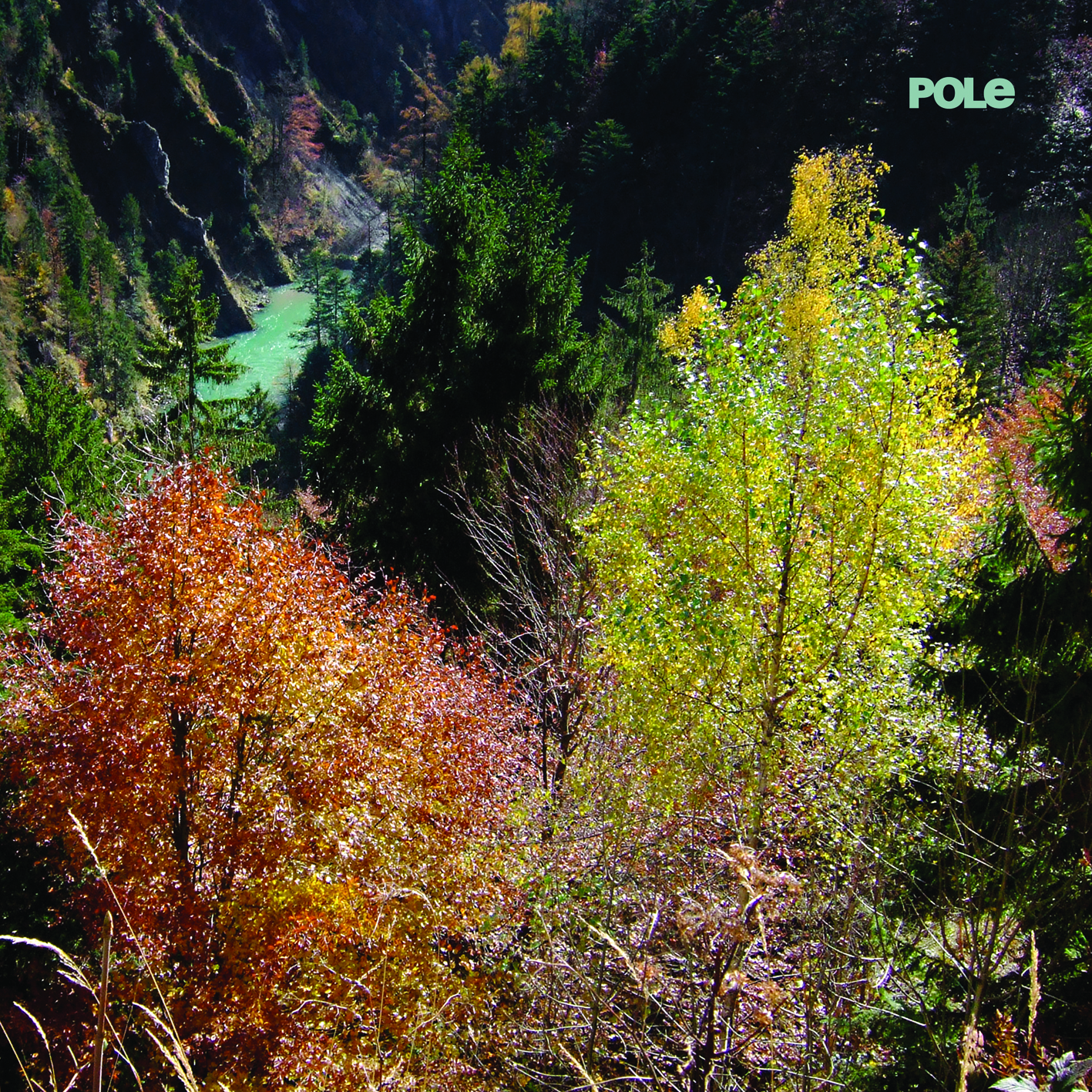

The photo on Wald’s cover is gorgeous. Where is that?

I took that photo on a walk in the mountains between Austria and Italy, on this very old path for smugglers who brought illegally killed deer and all that to sell in Italy. This was before the first World War. It’s now kind of a touristy place, with signs saying things like “Here they killed this guy or that guy.” [laughs] We were walking through there, and when I got to the top of the mountain and looked down to the valley, and I was like, fuck…that’s beautiful. So I took a photo—and that’s the cover!

The tracks are all named for things that you might have seen in your woodland travels: A käfer is a beetle, for instance, and an eichelhäher is a kind of bird. Does the music have any relation to those song titles?

Some correspond quite a bit, and some do less. Like “Kautz”: The music is kind of what really happened. I tried to transcribe what I heard into the music; I don’t know if it works, but that was the idea. The track starts with this mellow feel and nice bassline, kind of cool and relaxed—and then toward the end, there comes this distorted guitar-like sound, and then it stops abruptly. Boom! And that’s the way it happened. I was walking in the forest close to Berlin, and I was recording with a field mike. It was so quiet—it was amazing—and I was hearing my footsteps and all these little things around me, and all these elements…left and right, up and down, vertical and horizontal. And all of a sudden, a chainsaw started! They were cutting trees. Suddenly, all the animals flew away and the whole atmosphere changed. I took a photo exactly at that moment to capture it, and then when I looked at it later I could remember this break in the atmosphere. And I think the track does that as well—at least, I tried

The album is divided up into three acts of three songs each. Was there reason that you split it up that way?

The reason is connected to the A/V show that MFO [Marcel Weber] and I developed for the live presentation. We’ve already done it a couple of times, at MUTEK, at CTM Festival and some other places. We were thinking about how to connect the returning elements within the music into an A/V show that correspond to those elements. Marcel really liked the ideas of the kinds of circles and repetitions that return every year within the forest. We decided the best way to represent that circle was to divide everything into three acts, and I combined the tracks within those acts in a way that I thought was relatively narrative per each act—an intro, a climax and a fade-out. And then you go to the next scene; there’s a break in between, but that next scene follows in a logical way. They’re all connected, but the break is like a way of saying “please wake up!” [laughs] Like it’s an opera, it’s time for the next chapter of the story.

You’ve said in previous interviews that you weren’t all that well versed in dub music before you started producing as Pole. I still find that hard to believe, considering how adept you are at the sound.

It’s true! It’s really true! Of course, I was aware of it. I used to listen to a lot of the Clash, and also I was hearing Bob Marley and the more commercial end of it. But I was never that deeply into the music until I started working at Dubplates & Mastering, where I was introduced to the really interesting things. I know nobody believes me—but it is really true!

Speaking of mastering, is that still keeping you busy?

Yes—with the revival of vinyl, more than ever. It’s insane! Well, not insane, but beautiful. Vinyl is such a nice format. We’re booked up totally, and we work at it seven days a week, doing all kinds of interesting music. I still have a lot of fun doing it. I love it.