DeepChord: “I rarely see daylight in my music.”

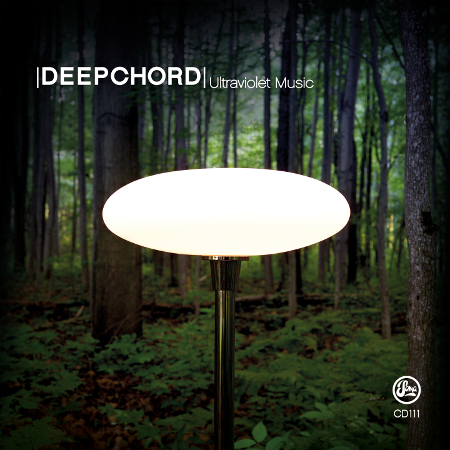

With the new 'Ultraviolet Music,' Rod Modell continues his quest for darkly beautiful places.

DeepChord: “I rarely see daylight in my music.”

With the new 'Ultraviolet Music,' Rod Modell continues his quest for darkly beautiful places.

“I think every geographic local has a unique vibration. I like places that have a nice majestic feel…I hunt for darkly beautiful places.” Rod Modell, better known as DeepChord, is going into detail about what inspires his music. The answer: Just about everything. It quickly becomes clear that the Detroit native is a veritable sponge for stimulus, citing everything from darkness, forests, fictional worlds, radio frequencies, and ghosts to sailing, photography, Soviet radar systems, and Amsterdam’s Red Light District as figuring into his ever-expanding catalog of inspirations.

“The sounds I use have to have a special metaphysical element or vibe,” says Modell, who also works with Stephen “Soultek” Hitchel under the Echospace banner. “This is the challenge.” We’re talking about his newest album, Ultraviolet Music, a two-disc collection of otherworldly transmissions just released on the Slam duo’s Soma Records. Despite its title and M.O., the album is more dancefloor-centric than one might think, while still drawing from Deepchord’s self-professed celestial influencs: air, water, night, and spirituality. He inhabits a strange paradox, at once bluntly honest about the frivolity of speaking about music (“I believe a good music reviewer would never resort to giving a piece of music a number rating because they understand that it is all arbitrary”) and yet simultaneously whimsical in his interpretation of it (“I think it’s entirely possible to distill the essence of a place into music”). It’s this kind of enigma that makes Deepchord, both the music and the artist behind it, so interesting.

When you close your eyes, what does your music look like?

To me, my music looks like a sea of static with transdimensional, transtemporal visualizations drifting in and out as sounds come and go. It looks like dark, rich, flickering colors being projected on the wall of a dark room. I always see my stuff being deep reds and dark purple or green. I never see bright colors. Always at night time. I rarely see daylight in my music. I like music that smears time and space. You don’t know if ten minutes or an hour passed since you started the recording.

Was that what it was like recording Ultraviolet Music?

Yeah, I mean, it’s electronic music with a pulse and nice, lush atmospherics —easy to get lost in. That said, I think this album is definitely more dancefloor-friendly, although that is really the last thing that I care about. It takes different inspiration from my other works as well—less by real places I’ve been to, and more by imagined spaces and terrain. I’m becoming less and less inspired by synthesizer sounds as time goes on, and more by organic sounds, ones that are impossible to create with synthesizers.

All the articles I’ve read about the album hang on this word “hallucinogenic.”

(Laughs) I think the possible misconception comes from illegal-drug connotations connected to the word. Back in the early days of techno, some of the best places to hear techno music in Detroit did not serve alcohol—places like the Music Institute or the UN. Allegedly, the music was more than enough of a drug by itself. I always felt this was true, and it was one of the things that drew me to this music in the late 1980s and 1990s. Alcohol and drugs actually dulled the experience. Seems like things are very different today. I believe music could be a drug in itself.

If you need drugs to make the music enjoyable, maybe you’re in it for the wrong reasons.

Exactly. I did several brain-hemisphere synchronization projects with a good friend from California, Michael Mantra, who sadly passed away recently. He taught me volumes about the vibrational healing properties of sound and importance of using “soft noise,” rather than utilizing harsh sounds that adversely affect the chakras. Mike had dozens of Tibetan gongs, and if I ever had some sort of ailment, he would send a particular gong to me that would correct the ailment. You would place the gong on the area affected, and the vibration would heal said ailment. It was very effective., more than traditional methods. In recent years, I’ve noticed hospitals and other medical centers finally acknowledging the healing potential of sound by forming sound-therapy departments. Universities are developing curriculums in this area of vibrational healing. Sound is becoming a legitimate method of healing the mind and body.

“I don’t think I would make any music if the ultimate end was just to make entertainment for people.”

For years I’ve been a fan of the healing music of Marcey Hamm. I truly believe music can have a drug-like effect, and some of the soundscapes swirling around beneath the bass and beats of Ultraviolet Music can indeed trigger visual sensations that listeners may not otherwise experience. So to get back to what we were discussing initially—yes, I do think “hallucinogenic” is accurate, but will be experienced differently by different people, largely dependent on their openness to it. In a way, any music that one feels strongly about could be hallucinogenic. I always felt music should be a tool rather than merely a means of entertainment. I don’t think I would make any music if the ultimate end was just to make entertainment for people.

Do you think music should awaken these kinds of visions in its listeners?

I believe so, yeah. There is music out there that scares me because the visualizations come rushing in so fast and hard that I want to pass out. But I have friends who listen to the same music, and it does nothing for them. So it’s a really personal thing. What affects one person might do nothing for another and vice versa. A certain artist’s work speaks to certain individuals and not to others—like, there are albums out there that I would categorize as a bona-fide religious experience, and I see one- or two-star reviews of that CD online.

There’s definitely something to be said about the musical religious experience.

Definitely. I think all music has an otherworldly connection—even terrible country and rock music! Establishing this connection is what artists do best, and the ability to make this connection is a prerequisite for any art. An artist needs to close his or her eyes, and draw from the ether around them. I think the air around us contains energies….

Energies?

Yeah, kind of like shortwave-radio transmissions. These transmissions are intercepted and converted into creative food. The broadcasts that a particular artist tunes into differ from artist to artist. We are all conduits for these broadcasts. Maybe someone with a strict religious background would pick up on more spiritual broadcasts, and those without a rigid belief structure may tune into more paranormal stuff. Creativity may come from within, but ultimately, that seed is from an external source. I don’t think I ever met an artist that didn’t have a true belief in these other realms.

You mentioned the paranormal, which is interesting because the press for this album has a description that I really like: “Middle of the night atmospheres, hypnotic repetitions, shortwave static and slowly evolving textures.” Paired with the album’s title, it gives me kind of specter-detector ghost-hunting vibes.

(Laughs) I think that’s accurate, yeah. Not so much the “hunting” element, but rather that there may be alternate realities occurring around us simultaneously, and these elements fade in and out from time to time. Shadow creatures or disembodied voices; sounds slipping in from other dimensionsl; nonvisual things becoming visible for a brief moment. I like to think there are souls of deceased friends and family still with us.

So you believe in the paranormal?

Of course. A belief in something bigger is definitely ingrained into my fabric. I’ve experienced way too many occurrences to deny it. These experiences are very subtle, and less perceptive people can miss them easily. Many people who don’t believe in such things basically switch off the mechanism in their brains that pick up on them. But they do exist.

In an interview of yours from ages ago, you said that you liked using hardware to produce because it made the music sound “alive.” Other than the right gear, what does it take for music to come alive?

I’m not really sure. Sometimes the wrong gear can make music better! Sometimes I go into my studio and record for two days straight, and a week later I listen to the tracks and don’t even recognize them, or wonder who’s music I’m listening to, like I was temporarily possessed with some creative spirit. Trying to recall what I did to make the music is like trying to recall what happened to me during a blackout period. I think whatever it is that I do—and I’m not really sure what that is ±just comes intuitively. Years ago, I made a conscientious decision to not overanalyze my music too much.

In the same interview, you said that digital music doesn’t have the same “life force” that you hope to create. It seems like maybe you’ve relaxed on those strict boundaries since then.

Yeah, I’m much more open-minded today. I think any form of instrument is equally effective; a tin can and stick can be as good as an analog synth for expressing yourself. I definitely think this life force is still important, but I’m much more open-minded about where it comes from, for example, I started putting my studio together in the mid 1980s. Synthesizers were a drug for me back then. I kept wasting money on better and better ones. I kept thinking new gear would make my art better, but in fact…the more I spent, the less creative I became. I’ve actually gotten out of synthesizers over the past ten years. They are extremely boring to me, really.

Where does that life force come from nowadays then?

You know, at one point, I wondered what elements exactly make a DeepChord song, and it was really difficult to figure out. Then I realized maybe I shouldn’t be trying to do that. Maybe I need to respect it as some kind of gift from the universe, and accept it graciously without nitpicking or analyzing it. Maybe if I really did figure it out, I wouldn’t be able to do it anymore. Maybe not knowing this is the reason I can keep doing it. Life is better not understanding some things fully.

Very often, when writing about your music, journalists will use a phrase, “unmistakably DeepChord.” Do you ever think about completely changing your sound, or is it part of you?

It’s part of me, but there are other parts also. I don’t know if being “unmistakably Deepchord” is a good thing or a bad thing. In one way it seems good because artists of all types spend most of their life attempting to develop a proprietary signature, so when people say this about me, I suppose it’s verification that this has happened.

But on the other hand, do you ever worry that this will pigeonhole you?

Definitely. It’s like an actor who played such a strong role that they’ll never be associated with any other role. They can’t break their typecast no matter how much they try. I think it’s imperative for an artist to eventually move on to explore new angles, or else whither and die artistically.

“Ultraviolet Music was inspired by those weird moments when you get a glimpse into another dimension.”

On that note, you’re obviously often associated with Detroit, the city where you grew up. Of that, you once said, “We are all a product of our experiences, whether we want to be or not.” What experiences shaped Ultraviolet Music?

This album takes a more holistic approach than previous ones. I like majestic sounds. Sounds that feel like there is something happening under the surface. I think the music is deeper than dance music. Ultraviolet Music was inspired by those weird moments when you get a glimpse into another dimension. This has been a technique that I apply to my music, much more than any particular experience. I think you should be able to listen to music for the tenth time, and hear something that you didn’t catch the first nine plays. The sonic equivalent of a Uta Barth photograph! (laughs) This album is really from somewhere else. I like music that reminds me of places that I’ve been to, and experiences that I’ve encountered there.

You’ve said similar things about your love of photography, which is your creative pursuit aside from music.

Right—I do, to an extent, live in my photographs. I don’t think I would be making sounds if I wasn’t photographing. I have a terrible memory, and carry a camera because I know if I don’t photograph something, I won’t remember it later. So I look at my photos daily, and go back to places I’ve been that way. You’re right that this has definitely been the case with past musical projects also. “Hash Bar Loops” is a great example, it chronicles my time in Amsterdam, and every track on there is a snapshot of something that happened to me there. “20 Electrostatic Soundfields” is also extremely like this. That album is a sonic photo album for me.

What kinds of places do you go back to when you listen to Ultraviolet Music?

This album contains sonic representations of fictional places, actually, stuff that I’ve researched inspired those songs: numbers stations on my shortwave, listening to AM radio static between stations, spiritual matter, etheric energy. It’s got a more otherworldly feel to it than other projects that were more grounded in a particular geographic location. Ultraviolet Music explores the airspace above the places represented on the other albums…air, water, night, radio waves, spirituality, and the possibility of other dimensions and multiple concurrent realities.

Photos: Marie Staggat

Support Independent Media

Music, in-depth features, artist content (sample packs, project files, mix downloads), news, and art, for only $3.99/month.