Bunker Records: The West Coast Sound of Holland

XLR8R travels to The Hague in search of the story behind the cult label.

Bunker Records: The West Coast Sound of Holland

XLR8R travels to The Hague in search of the story behind the cult label.

Founded by Guy Tavares in the early 90s, Bunker Records has long been a key institution of the wider acid and techno world. Over the course of the past 25 years, the label has been home to generations of producers from the latent Dutch scene, as well as a wealth of talent from much further afield, including Legowelt, Luke Eargoggle, Orgue Electronique, $tinkworx, and The Exaltics, to name but a few. On initial inspection, The Hague, a small city in the West of Holland, would appear an unlikely centre of electro music in Europe—and it was only by traveling there just last week to speak with some of the scene’s key players—namely Tavares, Rude 66 and I-f—that XLR8R really began to understand how a few punks successfully kickstarted a global musical movement from the very squats they inhabited. Philip Kearney tells the story.

“I feel sorry—the only reason why you are here now, is old glory. You only know me because of old glory. I’m from an era when things were still possible. The right time, and right place. We’re a bunch of idiots, who were just there at the right time.”

Guy Tavares is hardly boastful when it comes to his successes as founder of Bunker Records, a label that is oft dubbed Europe’s answer to Underground Resistance; yet his self-depricating comment is loosely verified by our surroundings as we speak. Happily submerged in an underground bunker of his own creation (constructed with junk found littering the streets above), he rarely sees the overground these days, still leading the same squatter life out of which the imprint was birthed.

He can be found six foot deep somewhere in the centre of The Hague, a city that sits on the west coast of South Holland. Most will be familiar with the city for its significant political stature—not only is it the seat of the Dutch Government, but also the International Court of Justice (the United Nations’ judiciary). Strolling around the inner city today, small as it may be, there is a distinct elegance to the architecture, punctuated by embassies and ministerial buildings. It certainly seems an unlikely setting for the birth of one of Europe’s grittiest electronic scenes.

Yet The Hague has been rocking the planet since the early ‘90s, the pivotal location in a movement that projected tough acid jams and electro rhythms onto a European platform. It is not only home to Bunker, but other strongholds of the sound such as Viewlexx and Murder Capital, DJ TLR’s Créme Organization, and more modern incarnations like R-Zone and BAKK. Only a stone’s throw away in neighbouring Rotterdam lies Clone Records, along with Frustrated Funk. It is certainly a fertile environment.

Another key player in the community is Ruud Lekx (a.k.a. Rude 66), a school friend of Tavares from the small town of Alphen aan den Rijn, who joined Bunker back in its early days. In his eyes, “Bunker is where it all started—it’s the genesis of the whole scene.” The first releases were distributed in 1992, at a point when nothing of its nature had previously existed. According to him, the other labels that quickly followed in their footsteps only managed it “because there was an infrastructure for it that was created by Bunker.”

It’s a position that Tavares agrees with, suggesting that his work was merely a “catalyst” amongst pre-existing talent: ”I planted the virus!” he jokes. Having ditched his biology degree at the nearby University of Leiden, Tavares quickly found himself dragged into the lively Hague squat scene. “We took advantage of it. I was very lucky at that point, as the city was moving out of a transitional phase. The inner city was empty, as the middle classes had left for the suburbs. It was completely bankrupt and fucked up. It looked like Detroit. Everywhere was full of squats, with junkies all round the House of Parliament! The Hague is not Holland, it’s something else. It’s hard-structured, with one side super poor, and the other super rich.”

Looking as far back as 1985, Tavares had been exploiting that unique demographic for his musical endeavors, throwing punk parties in the same squats he would later host techno raves in with the rest of the Bunker crew. It was both a musical and attitudinal facet that would stay with him for life (particularly through Motorwolf, a sister label specialising in garage rock and punk, which serves as an outlet for Tavares’ band Orange Sunshine). Lekx hazards a guess that the punk era set the parameters for how things would progress: “Our roots in that scene were always what distinguished us from other labels.” It’s a trait that he attributes to the labels who followed in their wake too, who shared “the same idea—a punk philosophy, doing it yourself. You have a network all over the world, and in every city there are a few freaks who will buy your music.”

“We couldn’t handle having commercial hands involved in our stuff, because then we would end up playing by other people’s rules. We can do whatever the fuck we want, and we still do. That keeps me going.”

More so than with other imprints, there is definitely truth in the idea that the Bunker’s magic lies in how things are handled—its spirit, its brand, and its design. Another long-time affiliate is Ferenc E. van der Sluijs, better known as I-f, who put out several records with them back in the early days, before going on to set up Viewlexx and Murder Capital. He doesn’t mince his words when he makes the point: “We couldn’t handle having commercial hands involved in our stuff, because then we would end up playing by other people’s rules. We can do whatever the fuck we want, and we still do. That keeps me going.” What was initially a last resort means of getting music distributed, at a point when no others were interested, quickly became a badge of honor—a “do it yourself” styled guide for action that has carried through to today, and set the blueprint for dozens of other local musicians to follow.

Quite unique to Bunker on the other hand is its penchant for all things military. Descended from lineage tormented by war, Tavares harbours a total obsession with violence and conflict, often misinterpreted as being an incitement towards it. In reality, he is more concerned with protection against it, often quoting the old adage “Si vis pacem, para vellum”—if you want peace, prepare for war. It’s an idea that filters into every aspect of his life, in his subterranean homestead that shelters him from the world above, and crucially into the label’s philosophy. Its name is nothing arbitrary, rather a real concept—a reliable, concrete institution, amongst the commercial minefield from which they seek shelter. Scan the discography and you’ll catch countless references to WWII, such as the sub-labels Atlantik Wall, or the more recent Panzerkreuz Records. It’s that same military punk archetype that roams the streets of Europe, but with a stronger dose of reality. “I’m used to heavy stuff. All my life, I’ve looked to the extreme things,” he declares.

It’s not the most typical backdrop for a techno label, but then again it isn’t a typical label. There came a point around the late ‘80s when the spark was ignited within the imaginations of these Dutch punks, put onto a new influx of techno records from Detroit and Chicago. Lekx describes the first time he heard acid house (via Tavares) as a “defining moment,” while for Tavares, it was ultimately the approach taken by Underground Resistance that was a major inspiration. At that point, when Jeff Mills was still a member of the Detroit supergroup, and the records were released as “just a disc, no pictures, no text. Just a secret code, in total blackness. That inspired Bunker.” The anonymity of their first releases testifies to that: minimal fonts inscripted on blank canvas, in a no frills approach that left everything to the music.

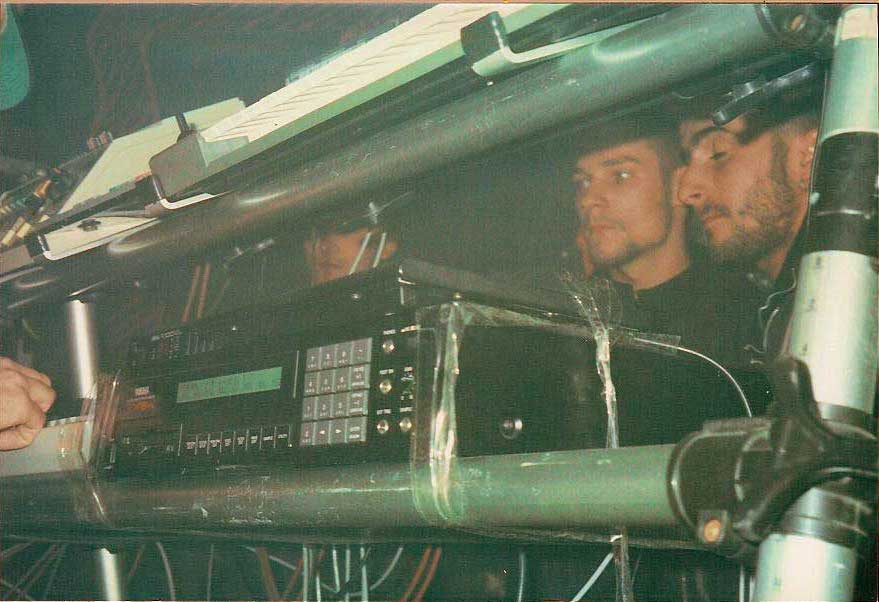

From the very beginning, that was essentially Unit Moebius—a group that shuffled formation over the years, but kept Tavares and his partner Jan Duivenvoorden (the act’s driving force) at its core. “I’m just a drummer boy, and Jan was the computer programmer,” explains Tavares. “I was the guy who did the mixer. Jan made shapes with his computer. He could handle it much better than I could. Most songs are by Jan, but on many occasions we recorded together live. I would give him tips—hum a bassline, or a high-pitched frequency, an alarm code from nature. I knew from my biological studies that would work. It’s like a survival stimulus. These kinds of codes are universal amongst animals. They give you adrenalin. We tried it out, and it worked. It was all one big behaviourist experiment.”

Over the years, Unit Moebius would go on to be picked up by other international labels (such as Germany’s Disko B, or KK Records of Belgium), and tour their music globally. Timeless music they created, constructed only with the bare-bones of what we might consider an adequately fitted studio today. It was a common feature amongst many of the records released through the imprint back then, true also of artists who would join later, which Lekx affirms in relation to his Rude 66 output: “There’s a lesson in those old records. You don’t need all these big mixers and expensive compressors. None of them were even mastered. I just had a very small Atari computer with Cubase, one sampler and a synthesizer. There was a DAT-recorder, and the music went straight through the mixer into the DAT, totally live. It’s all done with super minimal material.”

“In any other city in Europe, I wouldn’t have got Bunker to the level it is at now. Bunker is not me—it’s all the weirdos in the city.”

Soon enough, the label was home to what Tavares fondly describes as “all these other nerds, dandies and freaks” from the surrounding areas, who identified with the niche they had carved out. It’s a point that he keeps going back to: “There was the critical mass for it. In any other city in Europe, I wouldn’t have got Bunker to the level it is at now. Bunker is not me—it’s all the weirdos in the city.” In the years that followed, they picked up some of the sound’s greatest pioneers: Duracel, Ra-X (a.k.a Drvg Culture), Funkstörung, Rude 66, and I-F (who was taken aback by the “rough and impersonal music,” the likes of which hadn’t been in circulation before). Taking the acid sounds that had come to them across the Atlantic, and forcing it through their industrial and punk filter, they spawned something that matched the rough character of the city at that time, that still sounds fresh today.

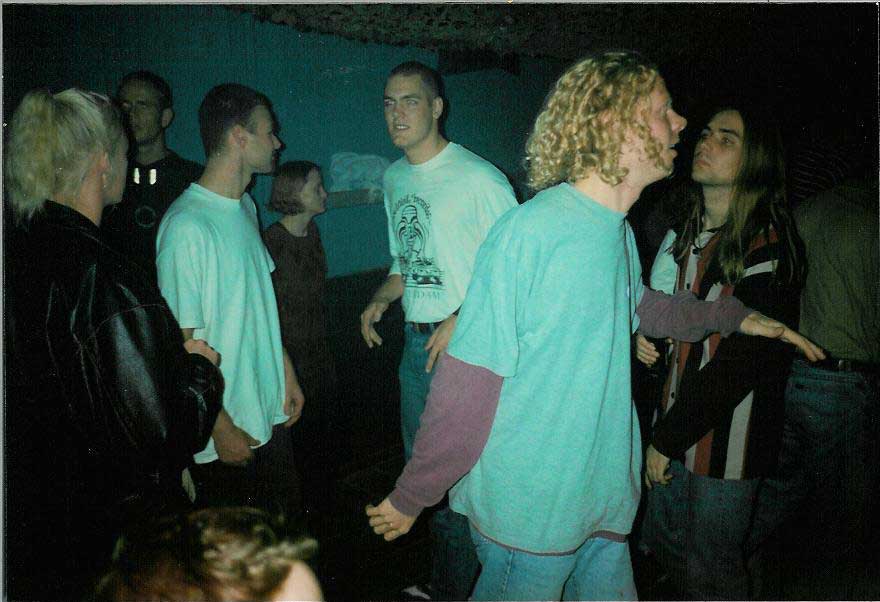

Digging deeper into the whole group, it seems that the Bunker parties (known as Acid Planet) were as significant as the records they put out, hosted at various squats around the city, including the notorious Blauwe Aanslag, a former tax office. By that point, the warehouse parties of the late ‘80s that had set the fire in their bellies, blazing with true anti-establishment spirit, had already been streamlined into mainstream culture and commercialized. A gap had opened, asking to be taken advantage of. Lekx reflects that that was what he “recognised in Bunker—they matched with the hardcore punk parties that we used to organise, just with different music. We were a bunch of freaks that had parties in squats. Nobody else was doing that by then. They were all hanging out in flashy clubs, getting dressed up! At our parties there were all kinds of freaks—office workers, homeless people, punks with mohawks, acid house freaks covered in smilies! It all just mixed, and it didn’t matter about your background, whether you were cool or not. Everybody just went nuts.”

What was a fundamental basis for their growth and development, was to become their undoing later down the line. Amongst a wave of distribution troubles and financial failings, the scene’s protagonists began to lose their heads. Lekx contends that “it was also the atmosphere at the parties, which had changed a lot—it all became very tense and aggressive. You could see it in people’s eyes, and then music was becoming harder and harder, faster and faster. Everybody took lots of drugs at those parties, and that was just part of the whole thing. There was a point though, where it wasn’t funny anymore.” Having almost reached 30 releases, Bunker shut down operations in 1997.

Fortunately it was only a brief hiatus. The same independent ethos that had kicked things off was enough to salvage the pieces of the label back from the brink of becoming history, with Tavares scraping together the funds to relaunch Bunker only a year later. It was a period that said good bye to the old, and welcomed the new. Taking inspiration from the musicians of their youth (such as Afrika Bambaataa, Hashim, and Grandmaster Flash), the crew dropped tough acid jams in favor of electro beats, and a host of new artists came on board. It would become home to the debutant releases of Hague locals Legowelt and Orgue Electronique, as well as looking further afield to the likes of Swede Luke Eargoggle, German act The Exaltics or Pittsburgh’s $tinkworx, amongst many more. Once again, it set a precedent for The Hague’s electro sound to flourish, delving into new, experimental grounds, and providing the platform for a wealth of musicians to mature.

“None of us intended our success. We’ll keep doing this stuff anyway, whether we sell it or not, and that’s the difference.”

Almost four years ago the label celebrated its 20th birthday—a feat for any institution, especially one which has been pussyfooting around the edge of bankruptcy and self-destruction for some time. It is testament to the strength of its artists, as well as its owner, whose main objective has always been to share in interesting music. Their longevity is a product of his compulsive nature, which to many would seem to verge on insanity, but to Tavares is the only way of life he knows. He stresses that even though it might often take a while, if he guarantees a release, it will happen eventually. “None of us intended our success. We’ll keep doing this stuff anyway, whether we sell it or not, and that’s the difference.”

It’s now been a couple of years since anything came directly out of Bunker, but there is still a healthy stream of activity pouring through the channel of Panzerkreuz Records, a branch that has so far looked back to more to heavy, industrial electronics, and to their roots in acid. Once more, it is at the vanguard of the sound, picking up acts like Helena Hauff, Sendex, Solar Skeletons, and even Slumberman (better known as Alessandro Cortini of Nine Inch Nails fame). Moreover, a rehashed version of the Acid Planet parties (known as Dystopia) continue in the same squat complex that Tavares resides in, held semi-regularly, and claiming to preserve the same vibe and ideals as the original events.

Before parting ways, Tavares makes one final comment, snubbing a comparison drawn by a friend of his a few years ago. “He said that I am like the William Burroughs of our world. A bum, an outcast, and a dandy, but also a link to an outsider culture from years gone by.” He may not wish to make a grandiose claim against one of the most prolific antiheroes of the 20th century, but the likenesses are there: Burroughs (famed for his books Naked Lunch and Junkie) has been cherished by countercultural movements worldwide for his link with strange, offbeat worlds and subversive sentiments. His highly intelligent mind was also afflicted by addiction and darkness, but his art was exceptional. Tavares’ appeal (though far more esoteric) is objectively similar—an innovator in punk-fueled electronics, to whom many other artists nowadays owe a lot. Without him and Bunker, it’s tough to imagine the West Coast sound of Holland today.

“The whole Dutch underground scene exploded, and it’s still going today. Labels are still popping up. There are new players, but the old players are still around. Everybody is still at it, and I find that pretty fucking amazing considering all the stuff that we did!” Van der Sluijs hits the nail on the head. Bunker is an institution unlike any other, for better and for worse. To dismiss it as “old glory” is an unfair indictment. Shrouded in mystery and legend, the cult of the label and its owner both have a special charm, with a lengthy discography full of classic tunes to boot. It may be surprising in some respects that it still lives on; yet in many others it makes total sense.