Drumcell: An Altered Shape

Marked by BL_K Noise and Hypoxia, the LA-based artist discusses the experimental side of his character.

Drumcell: An Altered Shape

Marked by BL_K Noise and Hypoxia, the LA-based artist discusses the experimental side of his character.

For most people, it’s their upbringings and early life experiences that shape who they are—and for an artist, it’s those years and moments that have paved the creative path. For Moe Espinosa (a.k.a. Drumcell and Hypoxia), it was a diet of early punk, industrial noise, and the explosion of rave in the early ‘90s that carved his path and artistic core. Add to that an early love of drum machines and synthesizers—particularly of the modular variety—and it’s not hard to see how he ended up where he is today.

But that alone is taking away the years of hard work and hustle that it took to get there. Currently operating in the upper echelons of a sonic space that is built on anarchic ideals and a desire to push past convention, Espinosa’s music, as both Drumcell and Hypoxia, flirts between muscular dancefloor cuts and more heady and cerebral outings. That music has found its way onto some of techno’s preeminent labels, including Chris Liebing‘s CLR, Blank Code Detroit, and his own Droid Recordings, which is the label arm of Droid Behaviour—a creative collective and event series Espinosa co-founded with Vidal and Vangelis Vargas (a.k.a. Raiz). It was the foundation of Droid that kick started Espinosa’s career—but the LA-based artist has since risen to be be a formidable voice in the expansive techno landscape. And although techno is what he is most known for, it’s in the experimental realm that Espinosa feels most comfortable. It’s a realm that holds little-to-no boundaries, which in turn gives Espinosa and his close circle of friends—pioneers like Richard Devine, Surachai, and Alessandro Cortini, to name a few—the freedom to explore the depths of their creative psyches and the outer-limits of sound in general.

This experimental side has been with Espinosa his whole life, but it was the birth and subsequent growth of the modular world that was the fuel to a fire that has now manifested itself into BL_K Noise and Hypoxia—the label and artist project that act as the vehicles for this side of his work. Originally conceived as a hardware-only after party for NAMM, BL_K Noise is now a fully-fledged vinyl-only imprint with a focus on concept, visual art, and the physical product. With BL_K Noise now on its fifth release, and with a new Hypoxia record in the works, we thought it was time to sit down with Espinosa to hear his story and to dig a little deeper into a part of him that, until recently, had only operated in the shadows.

Hypoxia – Wet Paper Cups (Performed on the banks of L.A river) from drumcell on Vimeo.

Where did it all begin for you musically?

Well, I was always tall and I grew facial hair really fast when I was younger, so I always hung out with an older group of people. I started playing guitar in about the 6th grade, at the end of elementary school. My older brother really introduced me to a lot of music, and most of that was rock music at the time. This was in the really early nineties. The grunge era, and a lot of throwbacks to the eighties; my brother listened to everything from Van Halen to Joy Division. When I was in the 5th grade, the first cassette I got was Smashing Pumpkins’ Gish; and I think that was what really made me want to play guitar. By the time I was in the 7th grade, I’d gone to my first rock concert. It was a Nine Inch Nails show and that kinda kicked me off diving into industrial music. Early Chicago stuff like Wax Trax! Records and stuff like My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult, KMFDM, and even bands from further back like Throbbing Gristle and the more noise-based stuff. I don’t think I fully understood it back then, but I knew about it. And I remember the first band I was in was kinda like this wannabe industrial band called Broken Machine. I played my very first gig and it was at a punk show and none of the punk kids were into it. It was like pussy shit to them. And that kind of catapulted me into getting into a punk band later. So I then spent most of the beginning of my high school playing in various hardcore-punk bands, ska bands, all of that. I was fronting the bands, writing the music and lyrics, singing. I was always writing music, songs came naturally to me. I always wrote shit.

I was right at the beginning of things kicking off in punk actually. Right when The Vandals were first blowing up, they had just put out Live Fast, Diarrhea. That was kinda like the LA we were in: The backyard parties with all of them playing. But it was about ’95 that I went to my first rave. It was New Year’s eve into ’96 at a rave called Circa. And that was when my entire life fucking changed. Everything changed from that point on; all I wanted to do was write music. I was playing guitar and I was fucking sick of drummers. I hated drummers. They were always a pain in the ass, always egotistical, always playing in other bands so they would never make it to practice. So I bought a drum machine and I started writing music with a drum machine.

Do you remember what the drum machine was?

I know the first drum machine that I would like to say it was, but it was actually a Quasimidi Rave-O-Lution. It was from the mid-nineties and it was super cheesy. But then the next one I got was a 707, and it was really cheap. I still have it, it’s the one in my studio, and it still works perfectly.

Right when I started to buy synths and drum machines, was right when software synths were barely starting. Computers weren’t really strong enough to handle the type of CPU power it would take to run a synth back then. I got my very first job at a recording studio when I was 17, that was the first working job that I ever had. It was in Hollywood, at a Latin-House label. I cut my teeth and learnt my chops there wrapping cables and various odd jobs and the studio engineer there taught me how to use Cubase vst and digital performer, some of the very first versions of software synths. I got in on the ground floor using the TR-909, 808, 303, and everything that was in that studio.

So you were you staying back and playing around all the time? Do you think that was a big part of you really falling in love with machines?

I think by that time I had already fell in love with it all. But it was all so far out of my reach; I could never afford any of that shit. Being in that studio and having access to it is what catapulted me into knowing how to use it all and being comfortable with it. It probably influenced me more to want to build my own studio and get my own shit and dive into it all properly.

It gave you the drive to really go for it.

It did. And from there, I put out my first record; I was seventeen when that happened.

On a label you also started, right? What was it called?

Well, it was with two other friends as well, so I can’t take all the credit. I had two older friends, Mike and Nate, and we started this crew called M.A.D. 12. We were fucking teenagers, it sounds stupid now [laughs]. It stood for “Music Always Dominates on 12”s.” We were actually trying to make scratch records. Because that was right when “turntablism” was at its peak.

Is that what type of music it was?

Yeah, it was mostly sample based. We made hip-hop beats, but electronic kinda-trip-hop—to use that term loosely. It was definitely electronic music, but it was more in the tempo range of hip-hop. We were sampling old science-fiction films, old vinyl records, and movies—we literally had an old VCR going into a sampler, sampling shit from VHS tapes. And we put together this whole fucking record, and on the back of it we put a photo of Pancho Vida. I don’t know why Pancho Vida was on the record, but he was. So we put that record out and it was a fucking hit! I don’t know what it was.

You sold out all the copies?

Yeah, and we had no distribution or anything. We did everything all on consignment. I mean, at the time, Melrose was full of record stores, like 15 stores. We had Beat Nonstop, DMC Records, Fat Beats, This Is Music, Wax Records—I remember all of them. There was Vinyl Fetish, which was the more industrial and goth store. But it was fucking awesome—it was one of the dopest spots! It was at the beginning of that whole rave culture and Melrose in LA was more like this hippie and bohemian place. People strung out sitting on the street smoking pot and ravers handing out flyers. We didn’t have internet and all that shit, so it was much more lively than it is now. You go to Melrose now and it’s like fucking dying designer clothing stores.

So when was the next release after this?

Well, I did a couple of dance-music releases that I will leave unnamed on a few different labels, particularly the label I used to work for. Records that went to test press but never really did anything or went anywhere. It was basically just me getting experience putting records out. But it was about 2001 when we formed the Droid Behaviour collective here in LA and we wanted to help re-kick start the techno scene here in LA.

Were you throwing parties or anything before that?

No, not really. I mean, backyard parties and desert parties. We used to throw these desert parties in the ’90s out in a place called Technopolis. We would go out into the middle of the Mojave desert to this lake bed called El Mirage Dry Lake, and we would to set up speakers and party—but it would literally be like blown speaker on the right and my friends from high school drinking beer in the middle of the desert. But it was about 2000 when I really wanted to buckle down and do this properly. We wanted to start a record label and throw proper parties. But all of it back then seemed like a giant pipe dream.

“….back then in LA, techno was this term people would throw around anytime they heard dance music.”

Were you already hanging around with the co-founders, the Raiz brothers, at that time?

Yeah I was. I met them through a college friend we both knew who knew I loved techno and was going to university with them. He was like, “Dude, I met these guys and they play techno. They’re going to play at this backyard party, wanna go check them out?” And I was skeptical, like, sure they play techno. Real techno? Because back then in LA, techno was this term people would throw around anytime they heard dance music. So I went to this backyard house party, and I remember walking into the room and they had these two Giant CRT computer monitors and they had two computer towers and they were both doing a live PA, with both of them on Rebirth. Like a really old ’90s 808, 303 software program. And I walked in, and they were playing fucking techno. And it was really fucking good, so we naturally hit it off. We became really good friends. They started throwing parties and we were throwing parties too. These were your typical ’90s house parties: Parents gone, throw some turntables in and play some records. So, we talked and wanted to do it for real. We came up with a concept and put out some records.

So, Droid Behaviour as the party brand—was that first?

Actually, no—the record label might have been first. The first record was me, as I had just finished my EP. We went out to Detroit for the first Detroit music festival. We went out there, I think we were about 20-years old, and it was the first time I had travelled out of the state by myself. Especially going to Detroit, it was quite an adventure for a 20-year-old kid. Detroit is a lot better these days, but back then it looked like fucking Baghdad. So we went out there and passed out the records and everyone was super into it. Everyone was totally supporting us and playing the record. I got a lot of instant, positive feedback from the release and was already getting a few followers and people emailing me. Droid basically started as a newsletter; our idea was to build this massive newsletter to send to everyone in the city that was even slightly interested in techno. Our mailing lists were populating to the point that we were getting lots of people coming to our parties.

Through a newsletter?

Yeah. The newsletter grew further than anything we ever imagined. Like, people have to keep in perspective that nowadays; people think newsletters are just bullshit. But back then, before Facebook and Myspace, it was an exciting thing to get. We always provided DJ mixes and stuff like that. So the newsletter got so big that we decided to throw our first party. And I have to be honest with you, we were pretty lucky. We never had a slow start. Like, from the first time we threw a party, it was slamming. Our second party was fucking incredible, and for the last 15 years that we have been doing shows, I could probably count one out of the hundreds of shows we’ve done that have been shit. The rest were incredible and not many people have had the luck to have that kind of track record. So I think we came in at the right time and in the right place where there was a big demand for techno. The people wanted it and we were young and had energy and drive. The first party we threw was with Daniel Bell and John Tejada. We threw it in the back room of a sushi restaurant and we fucking packed that place to the rim. There was sweat dripping from the ceilings and Daniel Bell absolutely destroyed the place. So the fact that we had momentum and things were happening, that always fuelled our energy to keep going and to never stop.

How long after that did the concept and idea for the Interface visual-focused party series start?

Soon after actually. Our first party was actually called Interface, and we always numbered them because we wanted to always remember what we were up to. But I would say that by the time we got around to about our 6th Interface party, all of us—me, Vangelis, and Vidal [Raiz Brothers]—had always dreamed of conceptually putting together the type of event that was more than just a party with a DJ. We wanted to create an immersive environment. Because often people are using visuals at parties, but it’s just an accessory at the event and it’s just thrown up on the wall and people come and nobody pays attention. We really wanted the visuals to be the headliner of the show; we wanted people to be captivated by them.

“You would take this little car into a room, that had like 360-degree projections inside of it and you would be beamed into the world of Tron with all these lights and visuals. I always thought how badass it would be to have a rave inside of that room.”

Where did the initial idea come from?

I remember some of our very first Interface meetings about this stuff I brought up this Disneyland thing. They don’t have it anymore, but back in the day they used to have this Tron ride called the Peoplemover. You would take this little car into a room, that had like 360-degree projections inside of it and you would be beamed into the world of Tron with all these lights and visuals. I always thought how badass it would be to have a rave inside of that room. That’s what we wanted Interface to be. Smoke and mirrors, using visuals and lights to immerse you into the world that we wanted you to be in.

And how did it take shape?

Luckily here in LA we have a big group of very creative people that worked in industries all over the creative spectrum. So we decided to do something that would blow people’s minds away. We started with a blank canvas and we just built an entire world that people could come to and just get lost in—and that was the idea for Interface from day one. And the first few shows that we did, I was just happy that people got it. People didn’t just want to come to the party and get fucked up and leave; they came to the party and immersed themselves in the whole experience. That was what I think separated what we were doing with Droid from a lot of other promoters throughout LA. Because, even though behind these screens everything was probably held together with duct tape and chewing gum, it appeared to look incredibly professional and well put together. From the outside it would have looked like we had our shit together, but we were basically using our shoe strings to hold it all together. We got a lot better over the years and these days I’d say that we actually are really professional. I think that meant something to people, that we cared enough to put something like that together.

And now that party has moved all over the world, with showcases in Detroit, New York, Amsterdam.

Yeah, and Denver, with one in Berlin coming up soon. Some of those cities have been many times too. We’ve been asked numerous times by various promoters who want to book Interface for their clubs too, but most of the time we’ve had to say no. There’s a certain level we have set for Interface and if it isn’t at that level, than we don’t do it. We’ve done Droid showcases where we’ve taken our visual guy Octaform with us, but we didn’t want to call it Interface. I’d have to say, the Interface parties we’ve done at ADE have been the biggest and most successful Interfaces we’ve ever done. The budget and the team that we work with and have access to over there are incredible. They saw what we were doing in LA and they wanted us there, so we were given really big budgets to do absolutely mind-blowing visual showcases with turnouts of like 3000 to 4000 people. That was on a scale that we would have never imagined.

So, when did you start working for Native Instruments?

Well, when we started Droid in 2000, I still needed a job to pay the bills. 9/11 actually had a huge impact on the industry here. At the time, I was working in various studios throughout LA doing engineering jobs. I was working with like Marvin Gaye III, Kool Keith, Dr. Octagon, George Clinton and the Parliament 5, and a lot of hip-hop producers like Battlecat. When 9/11 hit, my studio jobs disappeared as the whole economy just fell apart. Rented studios went down and people could just buy Pro Tools and record at home. So I lost that job and the first job that I got after that was at M Audio. I worked there for about a year until friends of mine that had moved on to work at Native Instruments drafted me to work in tech support in about ‘01. So Native Instruments became my full time job while I was running Droid. I could pay my bills and focus all of my energy on running my record label and getting my music out there.

“…if you want to learn how to work in a recording studio, then work in tech support where you have guys screaming down the telephone trying to get you to fix their studios. When you have that pressure, you tend to learn things much quicker than if you are just fucking around on your own.”

Did working there, especially in tech, change the way that you made and played music?

It was definitely an educational experience. Working in a company like that, as technologically advanced as they were at the time, also meant that there was a pressure for me to always keep ahead of the curve on new technology. And NI themselves provided a lot of educational opportunities—we had panels, discussions, and we learnt how to build reaktor ensembles. So that kind of advanced my knowledge of synthesis and what I knew about producing music to a whole new level. As a matter of fact, even though it was a full-time job for me, it was like going to university. I worked in tech support for six years and, let me tell you, if you want to learn how to work in a recording studio, then work in tech support where you have guys screaming down the telephone trying to get you to fix their studios. When you have that pressure, you tend to learn things much quicker than if you are just fucking around on your own. It was a really stressful job; I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemies, but then I moved out of tech support and into the marketing department. I wasn’t a marketing person per se, but more a product specialist. I was teaching NI’s artists how to use the products and stuff like that. I was very fortunate to meet a lot of DJs and shake hands with my heroes when I worked there.

You’ve had a long playing relationship with David Flores (Truncate). Was that around that time that you met?

Well David was actually in the Droid circle from the very beginning. David is a very timid person, whereas Vangelis, Vidal, and myself are outward and real go-getters. We have a hustler mentality, there was no time to sleep. I fucking worked nine-to-give, got out of work at five, and then would be in the studio, running the record label, trying to get distribution, trying to manufacturer records, working until five in the morning and then waking up and being at work at 9am looking like a fucking slob. It was a grind constantly. David was working too, but he always just made music for fun. For him, he didn’t seem like he gave a shit about putting out records or anything like that. He would just sit down and make tracks. But from the beginning, I saw an incredibly large wealth of talent in the dude. He made amazing music from day one. David has a long history of producing electronic music under a bunch of different aliases before Audio Injection and Truncate, different genres of electronic music and before anyone of us he was playing big festivals in Europe and stuff like that. David and I have always just got along, he’s one of those friends that I’ve had most of my life and I can only count a couple of times that I’ve ever had any type of conflict about anything. Some of the first Droid records that we did were collaboration records. Cell Injection was one of the first releases that David did on the label. It was actually the Cell Injection EP, we weren’t even going as Cell Injection as artists; it was the Drumcell and Audio Injection Cell Injection EP. That reached some pretty high charts. Speedy J and Chris Liebing supported it a lot and we started getting a lot of interest from people to do remixes together or play together.

Was that how your relationship started with Chris’ CLR?

Yes. Chris had discovered David and I through that record. He actually sent me a message on Soundcloud, and I never check my messages on Soundcloud. It’s the most useless part of Soundcloud, so to receive a message from Chris on there was funny. I had already developed a relationship with Speedy J before that and Chris had probably heard of me from Speedy. I remember Speedy J and I used to sit and chat on AOL messenger and exchange Reaktor Ensembles together. Total nerds. So I met Chris and he wanted to get a Cell Injection release on CLR, so we did a remix for him and that was the beginning of that whole relationship.

“I always felt more comfortable in the realm of experimental music anyway; I’ve never felt comfortable coloring in between the lines. And I don’t mean this in a bad way at all, but in a lot of ways, when you’re making techno, you are refined to certain limitations.”

Your latest projects are Hypoxia and BL_K Noise, and I assume you’ve been making and playing this stuff your whole career. What spurred you to kick start these projects now?

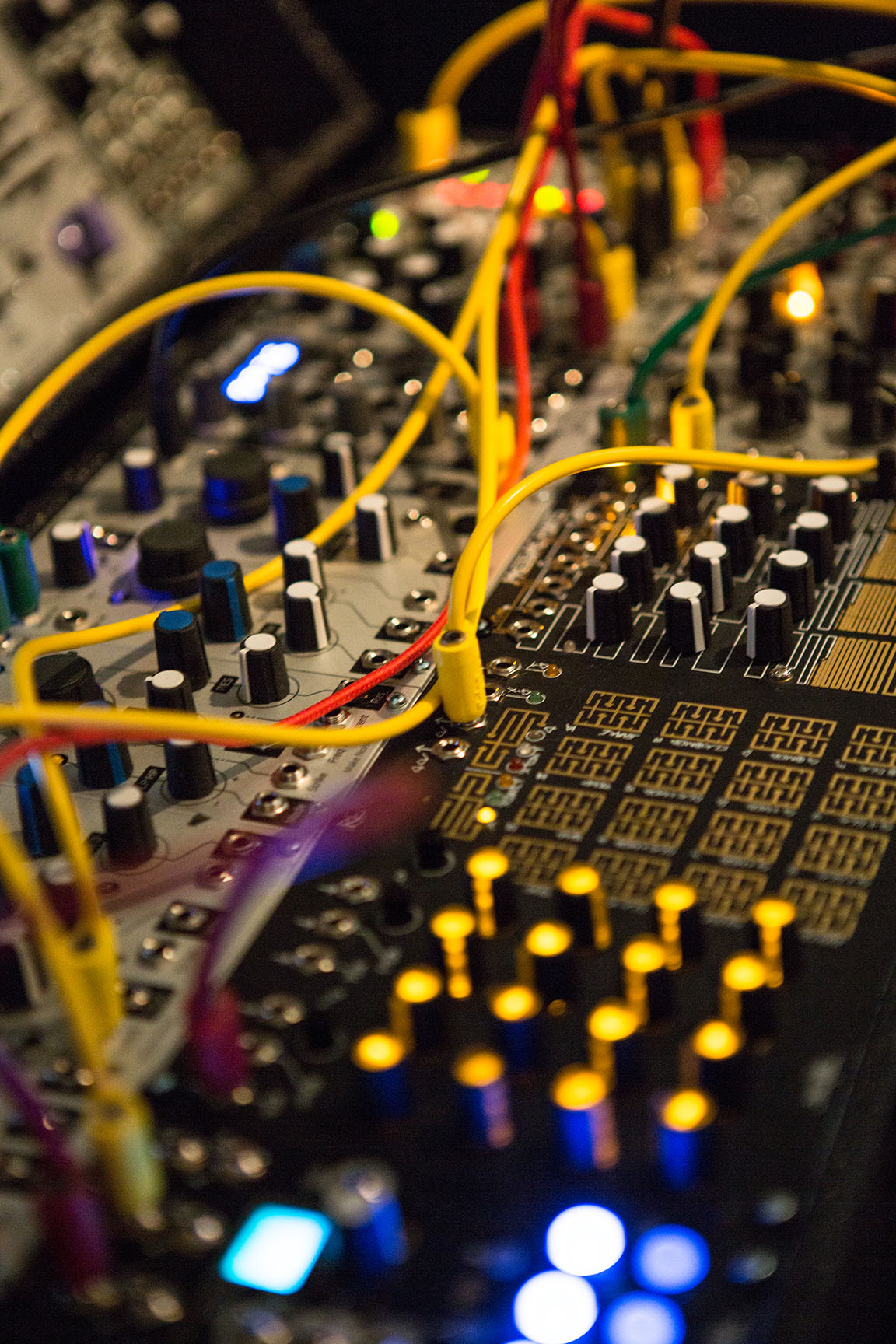

For the last ten years, we’ve been doing NAMM after-parties. About four or five years ago, we decided we wanted to start throwing an event after NAMM that was focused specifically on artists using hardware. Whether that was modular synths, or drum machines, or whatever, we just wanted only hardware-based performances. During NAMM, it’s a special time because all the manufacturers would bring all the new gear and our event became an annual thing where everyone wanted to attend, and those events actually started off as being called BL_K Noise.

How did it become a label, and why?

I have a very tight circle of friends, people like Richard Devine, Surachai—who I started BL_K Noise with—and guys like Justin McGraff and Alessandro Cortini. We’re also all part of this crew called Trash Audio, which is a blog where we talk about modular synths and stuff like that. So all of us in that Trash Audio circle started performing a lot at the BL_K Noise parties and I remember we would always record the performances and I thought it would be great opportunity to release some of that stuff. We never actually did, but that’s how the concept came about. But at the end of the day, Surachai and myself had outside pressures going on between us from our day jobs, or what we were doing at the time. For me it was Droid and for him it was his sound-design job. I always felt more comfortable in the realm of experimental music anyway; I’ve never felt comfortable coloring in between the lines. And I don’t mean this in a bad way at all, but in a lot of ways, when you’re making techno, you are refined to certain limitations. Because, at the end of the day, you’re writing music for DJs to perform with. So if those tracks aren’t working in a club environment and they aren’t making the dancefloors move the way that the DJs want them to, the records don’t do so well. And I think any artist in the world feels a tremendous amount of pressure of expectations because of what they’ve done in the past. I don’t always want to color in the lines; I don’t always want to make music with a 4/4 beat. I want to fuck around and I want to run a drum machine through a distortion pedal and feel inspired that way. So I wanted to start my own imprint where I could release whatever the fuck I wanted, whenever I wanted, without bending to the expectations of other people, and Surachai felt the same way. So that’s how the label started and we’ve done five releases now.

“Our idea was like this: Fuck distributors, fuck selling digitally, I like this record, I’m gonna press this shit and put it on Bandcamp. I’m gonna press 300 of them, and if I sell 20, then I’m gonna have 280 to give to my friends whenever I want.”

Was this project a serious business endeavor?

Not really. Our idea was like this: Fuck distributors, fuck selling digitally, I like this record, I’m gonna press this shit and put it on Bandcamp. I’m gonna press 300 of them, and if I sell 20, then I’m gonna have 280 to give to my friends whenever I want. And that light-hearted entrance into it was liberating. It was like this weight was lifted off my shoulders. That’s what I miss from when I was 17 and we were running around selling records, I didn’t have to worry about getting shitty reviews from somebody. That stuff can hinder creativity for an artist and I was sick of dealing with that shit. So BL_K Noise was a light-hearted endeavor; it was something that we wanted to do just for the fun of it. And that was how I did the first Hypoxia record: I sat down with my Buchla Music Easel and I hit record, I performed live, and I hit stop. Then I took that recording to a pressing plant and I pressed it on a record. There was no production, there was no mixing, there wasn’t months spent on the track. I finished the record in two hours. And I was sure that everybody that listens to hard, aggressive, industrial techno is going to fucking hate this pretty-sounding record. But I didn’t care. I made 300 copies, put it onto Bandcamp and it sold out in four days. Every copy of the record. And at that point, I was not prepared to box and ship as many records as I thought I would. Because I honestly didn’t think I was going to sell that many. It was a huge undertaking, but we did it. I hand signed and wrote a thank-you letter to everybody. I think what people gravitated to was that we cared about the physical product. We cared about how it looked, we cared to think that when you hold it, is it something that you want to collect? Or is it disposable? Because these days, the shelf life for music is bullshit. Nobody cares about a record two days after it’s been released. I loved it as a kid when you would buy a record, take it out and listen to it while reading the liner notes. You spent your lunch money on that record, you better love it. I’m trying to provoke people’s interest into music through the physical product. I just want someone to have a physical product that they can have in their house and cherish.

When did your love and obsession with modular synthesis actually begin?

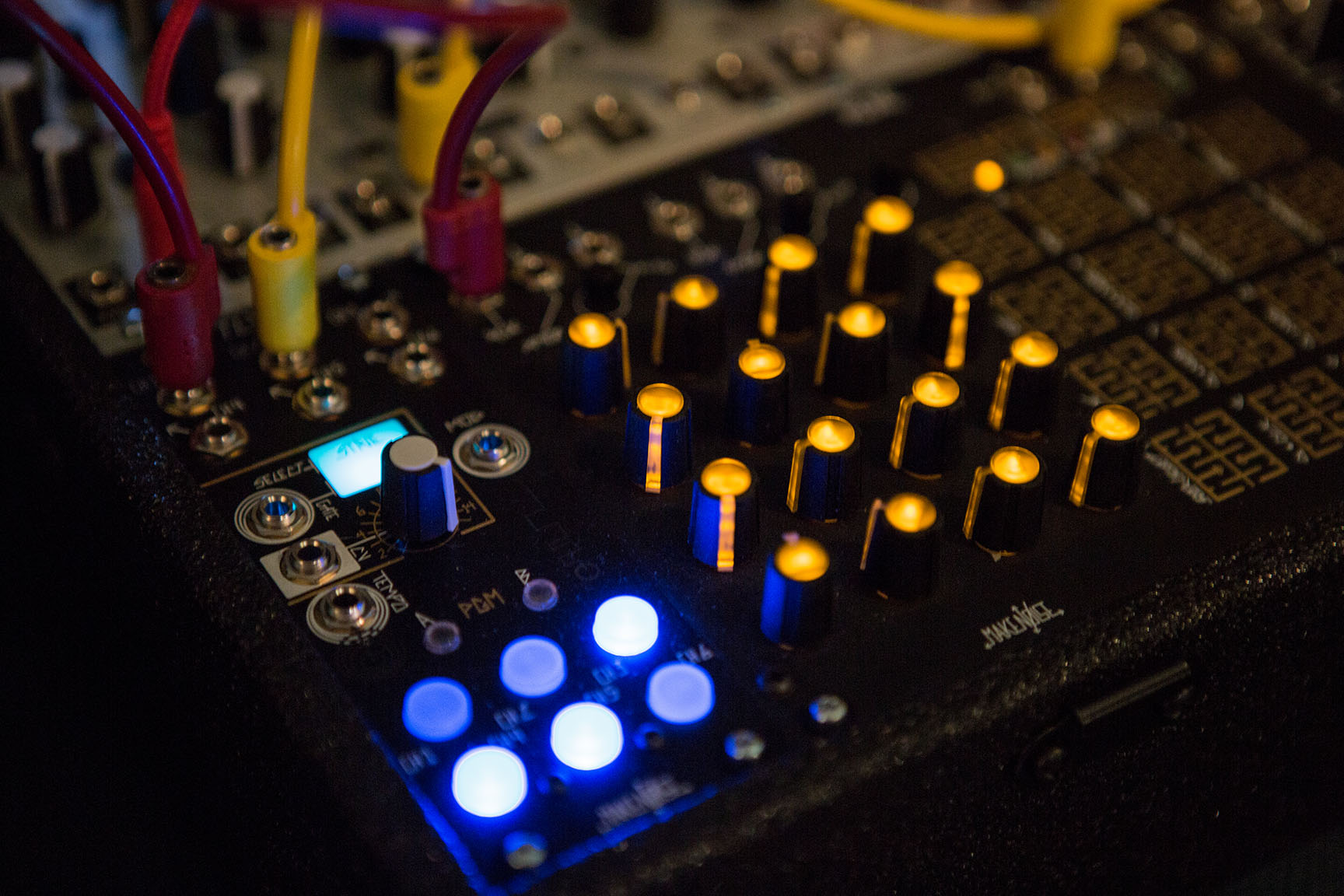

I’m really lucky I got into it on the ground floor when the modular thing was kicking off. That’s why I have such a good relationship with Richard Devine, Surachai, Alessandro, and those guys, because all of us we’re all collectors of modular synths before all this hype began. I mean, back then, there were only like three manufacturers: Doepfer, Make Noise, and Tiptop Audio had just started, and there was Plan B. I owe a lot to Plan B, because the guy who makes them, Peter Grenader, taught me a lot about how to use a modular synth. But there were only a few companies doing shit back then and I was kinda fortunate that a lot of the people making it were based here in LA. So when I was buying them, I wasn’t ordering it and having it delivered to me; I was driving to Gore’s [Tiptop Audio] house while he was making this shit in his garage. So were Richard Devine and Surachai. We were on the ground floor of this movement. It all kind of stemmed from not being good with synthesizers with menus. Whenever there’s a synth where you have to dive through menus and all that, I mean, I don’t even like to read manuals. I know how a synth works, just show me where the signal flow is and I’ll do it. And I loved that about vintage synthesizers, like the 303 and the Roland line, even the Prophet 5, everything was on the surface, the knobs were there, it was ready to go. So, these new modular synths provided a new instrument to obsess over and they were incredibly intuitive to me without having to dive into menus. And let’s be honest, the wires just look fucking really cool. I mean, fuck the hype, it just looks cool and it’s the aesthetic that hooks people. It looks like a weird science project, and that’s basically the roots of what techno is, you know? Experimenting with electronic instruments and creating weird sounds with it. And since I got in on the ground level, I’ve developed a really good relationship with a bunch of manufacturers.

Are those manufacturers still some of your favorites?

Yeah, for sure. I’ve done work for Tiptop Audio compilations and Tony from Make Noise is a great friend. The Hypoxia live set system is all Make Noise modules. I really like the idea of working with modules from one manufacturer, because it seems like one instrument and not a mixture of different systems. But I’m not hating on that either, it’s just the way I like to work.

So, with Hypoxia, you use the Make Noise system and the Buchla?

Yeah, the Hypoxia project originally started with the Buchla. But travelling with a Buchla synthesizer and being able to put on 40-to-50-minute performances can be quite challenging—I needed to expand my options and the Eurorack system became one of the best solutions for it. My case, when you open it, one part is for a particular song, then there’s another part for a different song, and then the Buchla is for a different song. I’m mixing between those from A to B like a DJ would with decks. While one patch is running, I have the opportunity to have another patch running so I can then mix into it.

So you’re using a mixer and basically cueing up the next track on another module?

Well, I’m performing one song while also trying to use the other half of my brain to perform something else, it’s stressful. DJing is a lot easier, it’s more like I know this track will work, I play it and the crowd goes nuts. The Hypoxia performances are a little more stressful for me because you’re playing an instrument. Like in a band, if you hit the wrong chord it’s going to sound like shit. The Hypoxia stuff is the same: I have to play all the chord progressions and everything in the same scale, or multiple scales, and I have to perform it and if I fuck up it’s going to sound like shit. But I like that challenge.

What are some of your most used or favorite modules or synths?

The Buchla has been big for me recently, I think it’s incredibly limited in regards to options, but I think it sound like a roaring beast! It sounds like you’re sitting in the belly of a bear, it’s awesome. I’ve also been heavily into all the Make Noise modules, I think what Tony does is incredible. All the Mark Verbos modules, which are inspired by a lot of the Buchla instruments, sound phenomenal as well. I dont want to sound like I’m favoring anybody because there is so much amazing shit out there. I’ll tell you what though, over the years, I’ve owned a lot of monophonic synthesizers and right now, more than ever, I have this obsession with polyphonic synths. Like the Prophet 5, the new Prophet 6, the old Korg poly synths, and the Jupiter, I just get a hard on whenever I see or use them. Because it’s been awhile since I’ve been able to play more than one note at one time.

What is your setup in regards to Drumcell now, you do a live thing with that too right?

Well the Drumcell live performance is heavily based on Ableton and Traktor, but I do use an external drum machine as well. The Elektron Analog Rytm, or Native Instruments’ Maschine. And that’s basically on a DJ mixer that has six channels, so I have four channels for Traktor, one for Ableton, and one for the drum machine, with an array of external effect processors as well.

So Traktor is basically the DJ vehicle, what about the rest?

Yeah, Traktor ends up becoming a big loop machine, I just grab samples and loops and parts of tracks, sometimes it’ll just be the kick, or the vocals, or the groove, or a bassline. Ableton has an array of stems from my own music that I’ve produced, whether it’s drums or some weird modular-synth jam that i’ve done. I kinda just mix that in there. The drum machine part is more the interactive side where I can sit there and improvise and add parts on the fly. It let’s me be more of a performer on stage, rather than just a button pusher. I’m traditionally a vinyl DJ, I was playing vinyl records my whole life, and I still play records today locally when I have the chance. But travelling with a crate of records is just not gonna happen. I remember when CDs were first being used and produced and being a vinyl DJ, we were incredibly prejudiced towards them. Like, fuck that, I’m never playing with CDs. But then I got into Traktor because I can play my own music without having to press it to vinyl, or a dub plate, and I can still use turntables. At some point, it transitioned to where the turntables in most clubs were so shitty that just playing on the computer became more viable. I developed the system of using the drum machine and turntable phased out. I just skipped the whole generation of using CDJs. David [Audio Injection/Truncate] ditched Traktor not long ago and is playing completely on CDJs now, and he just shows up with a USB stick and headphones and just starts playing and I’m sitting there with cables and I fucking hate him for that. So playing with CDJs is certainly opening up for me now, it’s something I’ll try to adopt in the future for sure.

So what’s coming up for you?

Well I just did my last release on Rodhad’s label Dystopian. That’s out now and I’m happy with it, which is funny because that record incorporates different elements of who I am. It’s got your more industrial track, the straight up dancefloor track, and a Hypoxia-like track on the B-side. I have two various-artist compilations coming up on Droid. I’ve got a record on Detroit-based label Blank Code, which is coming out next month, and I have the follow-up Hypoxia record coming out on BL_K Noise in June.