Ten Walls: A Musician in Exile

XLR8R coaxes Ten Walls from his studio isolation to face unanswered questions about his personal politics.

Ten Walls: A Musician in Exile

XLR8R coaxes Ten Walls from his studio isolation to face unanswered questions about his personal politics.

Though some seem willing to forgive, certain doors seem permanently closed for Ten Walls since his infamous Facebook rant. Over one year since he apologised, having refused all previous requests to speak further on the matter, Marc Rowlands travelled to Lithuania to conduct the first unfettered interview with Ten Walls since the crisis began.

Aside from occasional triumphs in their long loved sport of basketball, very little escapes the small Baltic nation of Lithuania and makes it onto the world stage. In May 2016 however, a controversial mural painted outside the popular Keulė Rūkė barbeque restaurant, located in the country’s capital Vilnius, went viral. Echoing the Berlin wall painting “Mein Gott, hilf mir, diese tödliche Liebe zu überleben,” it depicted Vladimir Putin kissing Donald Trump. The popular backdrop for photos existed less than four months before vandals daubed white paint across the image, obliterating the passionate kiss.

The damage unclaimed, nobody can be sure what the motivation for the defacement was. Anti-Russian sentiment in some quarters is unsurprisingly high here, as it is in many former members of the Soviet block. But Lithuania is also a very traditional society. Its Catholicism is more visible after years of stifling under communist rule, to the point where the church now interferes openly in national politics.

Lithuania’s track record on LGBT rights is not the greatest. Although anti-discrimination laws exist and gay people may serve in the military, civil same sex partnerships are not recognized, gay marriage is not legal and a law comparable to the UK’s Section 28 prevents promotion, although effectively this means mention, of homosexuality in the education system. Homophobia is not uncommon. Could the literal whitewashing of this mural have been provoked by such attitudes?

Prior to the painting’s mass publication, it’s unquestionable that Lithuania’s greatest recent cultural export was Ten Walls. A pseudonym for Marijus Adomaitis, a producer who had already achieved significant success in Lithuania and in underground electronic music circles as Mario Basanov, Ten Walls entered public consciousness in 2013 with a stand out release and a change of style that accompanied his new alias on the Gotham EP. Released by Innervisions, the record was followed later that year by the Requiem EP, another triumph that trod a similar path, boasting an uncommon, heavy bass sound that seemed to mimic an orchestral brass instrument.

This inspirational shift in direction was truly crystallized in 2014 with the release of hit single “Walking With Elephants.” This track did more than just shake a few dancefloors: it was a top ten pop hit in the UK and an anthem across the festival circuit, the Mediterranean and Balearic Isles that summer. In early 2015, Ten Walls won a M.A.M.A. (the Lithuanian equivalent of a Grammy) for Best Electronic Act, “Walking With Elephants” received one for best music video and later that year was nominated for Best International Video at the UK Music Video Awards. The track has since gone on to be performed by the Royal Swedish Orchestra. Thanks to “Walking With Elephants,” Ten Walls went from being big in Lithuania to being huge almost everywhere.

It was in the first days of June 2015 that Ten Walls, known to his friends as Mario, found himself alone with his PC in his London hotel room, amidst a tour propelled by the success of the release. Quite what frame of mind he was in that afternoon, or perhaps what YouTube wormhole he had unwisely chosen to travel down during his free time, is anyone’s guess. When questioned, he only describes his state as being in “meltdown,” exhausted from a touring schedule that had clearly made him lose significant weight, let alone sleep. What next occurred can hardly be explained or understood and certainly not excused by any attempts to assess his mindset at the time.

Mario’s infamous Facebook post appeared in the Lithuanian language, each of its three sections followed by links to YouTube videos in Russian. The text was angry, confused and barely coherent according to Vilnius based filmmaker and gay rights activist Romas Zabarauskas, who translated it to English and began its dissemination to western media sources (actions for which he’s since received death threats and been lampooned as a “snitch” on a satirical national TV segment). Within the rant, Mario had railed against modern day tolerance, talked about people of a “different breed” who, via way of the second video, he suggested should be “fixed” using violence. He recounted a discussion with a friend where he’d asked, using gross and graphic language, how the friend would feel to learn his 16-year-old son had been on the receiving end of gay anal sex. He also recalled witnessing a public remembrance of paedophilia victims while on tour in Ireland. To many the inference was clear; he was linking paedophilia with gay sex and therefore with homosexuality and that is how it would go on to be reported.

The original post disappeared within an hour as, eventually, did the unintelligible and wordless texts of random letters also posted on Ten Walls’ Facebook page several times that same day. But it was too late. Zabarauskas and others had already noticed. Clarification, explanation or apology was sought. No reply came and so the translation made its way first to an LGBT news portal before being taken up by the world’s online music media.

The fallout was spectacular and overwhelmingly unified. Although a short apology had appeared on Ten Walls’s Facebook page within days, this seemingly wasn’t enough. Its sparse wording was regarded as mealy-mouthed, not accepting of responsibility and insincere. His booking agency, Coda, dropped Ten Walls, as did major festivals like Creamfields, Sónar, Urban Art Forms in Austria, Pukkelpop in Belgium, Mysteryland in the Netherlands, HARD Summer Music Festival and Amsterdam’s Pitch. DJs such as A-Trak, Tiga, Knife Party and Optimo took to social media to condemn his comments and Fort Romeau cancelled a forthcoming appearance alongside him. Even the Lithuanian president, Dalia Grybauskaitė, who had just one year earlier publicly congratulated Ten Walls for the chart success of “Walking With Elephants,” weighed in. She said the resulting discussions would benefit the country, acknowledging their difficulties with being insular, stating “the sooner Lithuania becomes more open and more tolerant, the better it will be for the country.”

It took until September for a fuller apology to arrive, in which Mario expressed shame, regret and took full responsibility for his actions. He insisted his initial post had been out of character and that he’d never been a homophobe. It was translated into a better fluency of English than Mario is capable, although it was still not perfect; it inferred that his forthcoming project, an electronic version of the opera Carmen, would have a strong message of LGBT support, acceptance and tolerance within it, which, to those knowledgeable of the opera’s storyline, seemed improbable.

In early December 2015, Ten Walls released the track “Shining,” featuring transgender singer Alex Radford. It was premiered and made available as a free download on the website of national Lithuanian LGBT organisation LGL, who stated they were happy to build bridges rather than have walls remain between Marijus and the country’s LGBT community. The release went largely unnoticed in a western media still unwilling to offer coverage. It was regarded cynically in some quarters as a PR move, initiated to get his career back on track, suspicions also levelled at his previous attempts to apologize. Almost nobody was aware that this supposed PR stunt was not in fact Mario’s first collaborative effort with the singer and that their relationship stemmed back to 2012, when he released the “Like A Child” single with the then Athena Radford.

I first made contact with Ten Walls and his people in November 2015. He had refused all requests to be interviewed on the question of the sincerity of his apology or about his Facebook post, but I felt it still required discussion. Did he accept responsibility? Had he had a change of heart? Had he been educated and forsaken any homophobic views? Did he know that a homosexual was not a paedophile and that saying so was offensive and completely unacceptable?

My approach for an interview to clarify the situation was refused, although an offer to talk about new music was offered. He’d apologized twice, atoned for his actions—there was nothing more to add, the story was over, it was time to move on. Mario’s apologies had been enough for many of his fans, particularly in Lithuania, including some of his gay fans there, eager to see their champion export back on top.

“Audiences now seemed split. Gone was the unified response condemning his outburst. Some remained entrenched in the view that his apology and atoning actions should be viewed cynically and he should remain outcast as a homophobe. Many others, including gay fans, were more conciliatory, accepting of his apology and willing to give him another chance.”

“He’s apologized for that, let him continue with his music,” 19-year-old Vilnius resident Martynas tells me. Martynas and his boyfriend are three months into a relationship and can barely let go of each other in public. Although we speak in a bar that is not even regarded as gay friendly, their kisses and affection go nearly unnoticed and wholly unchallenged by the almost exclusively male, middle-aged and straight clientele inhabiting other areas of the bar. This is behavior and response that would be hard to envisage occurring in many other eastern European cities. Martynas’ boyfriend, Benas, 18, who has himself been impacted by homophobia, is less verbose on the subject of Mario Basanov. “He makes great music,” his sole remark, offered with a shrug.

This visit comes as Ten Walls’ people finally agreed in July 2016 to grant me an unfettered interview. During my visit, I would also get to see the debut of Mario’s version of Carmen. I had reapproached Ten Walls’ people following yet more cancellations, including his date at Circoloco in Ibiza, which he explained was because “a number of DJs refused to play on the same stage with me.” The following month Movement Festival, Croatia and Pleinvrees Festival, Holland were also cancelled. These dates were to have been part of Ten Walls’ “Equalized” tour, intended as a comeback and to promote his 2016 Italo EP. Starting in mid-April, the “Equalized” tour had proved so popular that it was extended, visiting Naples, Belgrade, Lisbon, Istanbul, Budapest, Antwerp, Milan, Prague, Abu Dhabi, Hammamet, Constanta, Timisoara, Makarska and Tbilisi. Perhaps tellingly though, there had been no dates in France, Germany, the USA or the UK, and he was still not appearing at major festivals.

The matter clearly remained unresolved, in the media, within the industry and certainly within dance music’s wider community. This was more than evident both in the comments sections of news stories that announced his Circoloco cancellation and on Ten Walls’ own Facebook page. Audiences now seemed split. Gone was the unified response condemning his outburst. Some remained entrenched in the view that his apology and atoning actions should be viewed cynically and he should remain outcast as a homophobe. Many others, including gay fans, were more conciliatory, accepting of his apology and willing to give him another chance.

Two days prior to seeing the debut of Carmen, I am driven to Ten Walls’ studio by Egle, the PR representative who I have long been in negotiations with. Located some 20 minutes outside of Vilnius city centre, within the grounds of the national TV and radio station building, I am met there by Mario’s wife, Diana, who also acts as his manager. We are joined shortly thereafter by a man who I later learn to be the boss of the PR firm for which Egle works. My encounter with Ten Walls will clearly not be a one-to-one affair.

Mario arrives, wheeling around the forecourt on a BMX. He smiles and greets me warmly. Although his comfortable looking clothes are loose and baggy, he is noticeably thin beneath them and while he is bright, alert and attentive, his face displays the tell-tale signs of many late nights and an exhausting work regime. We break the ice over sushi. Everyone is chatty, the conversation relaxed and open.

Mario’s English is pretty good, so much so that his request for a translator to be present is dropped at the last minute, although he occasionally seeks clarification from one of the better English speakers. In conversation he is confident, forthcoming and at times physically animated in the extreme, especially when talking about music. He mimics the playing of instruments as we discuss his education (he spent 12 years from the age of five being classically trained in music, with the bassoon his chosen instrument). When discussing Carmen, he at one point rises to his feet and dances as though part of a ballet. His playful, uninhibited and at times goofy behaviour draws laughs from everyone surrounding the table outside the studio, where we are all relaxed—eating, drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes.

Mario persistently veers off on tangents as he talks. On many occasions he prefaces answers to questions with the word “firstly,” as though he intends his response to have multiple parts; they never come. He loses himself in further explanation, rather than referring back to the initial question, which he several times fails to keep track of altogether. In the first few instances this could come across as nerves, but over the course of several hours it becomes apparent this is just how he talks. He is intelligent and friendly, but clearly not the most socially adept individual.

Mario was brought up and schooled in Kaunas, Lithuania’s second city. He had a happy home life. His brother, who is seven years his elder, studied under the same music teacher as both his father and grandfather and has since represented the country as a singer at Eurovision. Mario describes the atmosphere at music school as “very artful. We never had fights.”

“One summer the boss of [the] studio where my brother was working had a problem with the alarm and asked me to watch the studio as a security guard at night,” says Mario of a pivotal moment in his mid-teens. “All summer I was studying some spiritual stuff, Hare Krishna and sanskrit, and at night, I was in the studio. I made my first album in 1998, it was drum n’ bass.”

“I’m a Christian and this is a Catholic country. I believe a lot in Jesus’ lessons,” he begins, when asked to explain his brief flirtation with the Hare Krishnas. “I am not going in the church, but I believe in Jesus. What was interesting about the Hare Krishnas was they would talk a lot about the God. Not Mary, not Jesus, but a lot about God.”

After finishing school, Mario got into music academy in Vilnius, but by that time his head had already been turned by electronic music. Without graduating, he returned to Kaunas to instead enrol in the first intake of a new music technology course. Finding the tutoring too simplified for the advanced stages he had already reached alone, again he did not finish, instead going to Hamburg to enter a competition centred around remixing Wagner. When he returned, in 2005, it was to Vilnius, where he started to build the studio which became the workspace outside of which we now sit.

“After you’ve been in classical music for 12 years, sometimes you just want to run from it,” he says. “So, when I finished my studies I concentrated only on electronic music… I started as Mario Basanov in ‘98, but really as an artist in 2010,” he says (although prior to 2010 he had started to work on commissions for Lithuanian pop stars, which now totals some five hours worth of recordings). “I was worried to change my name,” he says, of the start of his life as Ten Walls, “because you never know if a new project will be successful. But it was.”

The evidence of this success is on display inside Mario’s studio, a beautiful and comfortable environment in which there’s little doubt this self-confessed workaholic has spent many hours making music. A huge collection of video games, which he describes as “one of the biggest inspirations of my life” attest to his music-making being not the only time he spends cocooned in the space. I ask if he has any ambitions to score the music for such games.

“I have many ambitions. I would like to play in clubs and at festivals with dance music. I would like to play one time a year with a symphony orchestra,” he says, before again veering off. “I make music not only for myself but to make people happy. To see thousands of them enjoying your music is something that’s really special. It’s an amazing feeling when you play for 10,000 people. I would also like to make art exhibition performances.”

“And what about soundtracks? If not for video games, then for movies?”, I ask, already aware that Mario has produced one film score, a low budget 2012 movie by Latvian director Māris Martinsons titled “Tyli Naktis” (Christmas Uncensored). The film centres around a family with a traditionally minded patriarch who, amongst facing other issues, discovers his son is gay.

“It’s a post Soviet story about a family in Lithuania,” explains Mario. “Some are very conservative people and the film analyses many problems that happen that night, including homophobic problems. When you are making [this] music, you must understand how those people feel. I am trying to create the emotion of how they feel inside, because they are hiding.”

“In comparison to the earlier relaxed atmosphere, as it’s become apparent we have moved into new areas of discussion, the air has decidedly changed. Everyone around the table is silent aside from myself and Mario.”

“I think people might be surprised to learn that someone who is seen as homophobic would agree to work on a film with such themes,” I say, after learning that Mario spent hours watching the movie alongside the director while designing the score.

“You know how many artists I produced in my life?” he says, adamant that he is not, nor has ever been, homophobic. “This is not ego, but this five hours is not for nothing. Do you know how many gay people there was? Many. Do you know how many gay parties I played as Mario Basanov? Many. Do you know Horse Meat Disco? I played that party. How can I play this party if I am homophobic?”

It’s true that Mario Basanov played a Horse Meat Disco party at the start of 2013, although it was not their unrelentingly gay hometown residency in London, but a Horse Meat Disco party at Wanderlust in Paris, curated by the venue.

In comparison to the earlier relaxed atmosphere, as it’s become apparent we have moved into new areas of discussion, the air has decidedly changed. Everyone around the table is silent aside from myself and Mario, who is no longer animated, but transfixed to his chair, gradually looking more and more uncomfortable as the questioning progresses.

“I never wrote anything that linked gay people with paedophiles,” he insists. “I never called them another breed. In my post there is no gay, no homosexual, no nothing. My post had three chapters. After each chapter there was a video. You know, it’s very hard to talk about this. I would like now to talk about Carmen, about house music…”

“We will talk about Carmen, but we must talk about this.”

“We must,” he relents. “I would like to tell, because people ask me and this is the moment I can tell. This post is bad translated. The first post is about a Russian actor. People ask him “You are cool to watch porn with animals?” He says “Yes, it’s inspiring me”….

“First, I was in London when I wrote this. I was in meltdown. It shocked me, because I was very nervous. Second, cause it’s wrong to talk about animals, you cannot use animals. It is wrong. And in the same post he says ‘Is it true you are walking naked through (sic) your little daughter?’ ‘Yes, it is true.’ And after this one, you know what the link was? The link was Ten Walls linked gay people with paedophiles. No. Never. I linked this guy, who talks about animals and his little daughter. Another breed I write not about gay people. Never. I called that actor who was talking too crazy, by my opinion. And it was badly translated.”

“What did you think about the reaction to the story?”

“It was highlight, it was everywhere. It was written that I said another breed. I never said that about gay people. Nobody listened to me. Nobody heard me. The only thing I can do is with my work. Vilnius City Opera director Dalia Ibelhauptaitė called me. Five years ago we made electronic opera compilation. She said ‘Mario, I think now you have time to make Carmen with me,’ and so we started to do Carmen. And yesterday I finished it. And I thought, [there] is only one way—when nobody listens to you, is to make by your works. I am a guy who if he’s in good mood or if he’s in bad mood, I always go in the studio. I’m addicted to making music.”

“But what about the problem that was still there? You thought that it would just go away?”

“I am not Messiah, I cannot say what will happen. I have my ambitions, I see that my fans is growing up on Ten Walls page. I can see my Equalized tour was absolute success, full packed.”

I change tack. “You know that a homosexual is not a paedophile?”

“Of course. Everybody knows. Paedophiles are criminals, they are raping people.”

“Do you support gay marriage?”

“I don’t think about this. I have my [gay] friends, I don’t think about politics. I think only about music.”

“Well, think about it now. Do you think it’s a problem for gay people, either two men or two women, to get married?”

“They have their life, I have my life. I’ve said what I can tell. That’s it. I’m a musician. Everybody has their life.”

“OK, but if you watch the news or if you go and vote, you must have an opinion on some things. Nobody’s life is only music.”

“Well, I never vote. I never vote in my life. Maybe one time, if my mother said to me ‘go and vote, this is good, this is not Communist.’ Really. I am a musician. I am not a warrior. I am not a fighter. I am very open-minded. I am very friendly. I had so many friends, so many clients, so many singers, so many artists [who were gay]. They have their life.”

“What do you think about gay people adopting children?”

“I never thought about that. Really? You want to talk about this?” “Yes.”

“But I don’t know what to tell you. I can tell you about the notes.”

“I want you to tell me your honest opinion. Because I think it would help people, who maybe like your music, but who are not sure about who you are, better understand who you are and what you think. Can you tell them what you think about gay people getting married and adopting children?”

“I really don’t want to talk [about] what I don’t understand so very well. To talk about politic, I don’t know the things to talk about politic. Now this… I don’t know. I’m thinking about…. now I’m thinking about Carmen! I’m thinking about my album, I’m thinking about my wife, I’m thinking about my friends.”

“Yes, but now you are here with a journalist who is asking you these questions. So, I ask you to now think about these things. Tell me what you think. Is it a problem for you for two men to get married?”

“For me is not a problem,” he says quietly.

“And for a gay couple to adopt a child?”

“For me it is not a problem, but I am not an expert to talk about this.”

“Yes, but you opened the door to talking about these things because of what you wrote on Facebook. And people would like to hear, so I ask for you to comment on it.”

“Of course they would like to hear, but the main thing is I cannot tell you the answer because I am not an expert.”

“You don’t need to be an expert to have an opinion.”

“I don’t know so many things. I know that I have my friends.”

Mario has quietened to his lowest audible level by this point and the tension around the table is palpable. He is clearly uncomfortable discussing these issues. Mario’s two PRs don’t try to interrupt, defend or speak for their client. Any thoughts that this interview might be impeded by their presence vanish as they let him speak for himself. In the end it is Mario’s wife who interjects, breaking the unsettling near deadlock.

“We actually have [gay] friends who are already in a marriage,” she says, “and we are happy because they are happy. It’s their choices. If they need this, if they need a marriage, if they need an adoption. Ask these people. Only they know what they need, because they are living this life. What can we do? Just let them choose. Like Mario said, we are not experts and, for me, I’m not cool with some [straight] men and women who want to adopt children, because they are drinking alcohol, living bad lifestyle. So, maybe sometimes it’s better for gay people to adopt these children, if it’s a nice family, they have a good job, they can do education for this child. So, it always depends on the people.”

“Do you agree?” I ask Mario.

“This is my wife,” he answers unequivocally. “We are going in the same road.”

“Would you be happy to play at an LGBT party or festival?” I ask.

“Of course. I already played. In 2012 I made “Like A Child.” I played with Horse Meat Disco. Milan fashion week, I played so many years. Guys, come on. I produced so many artists. It was bad translation. I’m telling you again, there was nothing about homosexuals. I call that actor who talk about animals and I call paedophiles another breed. I am very uncomfortable to talk about this. I can talk so many other things, like religion…”

“Well, some religious people don’t agree with homosexuality,” I offer.

“Let’s talk global. There’s only one God with different cultures,” he swerves.

“Yes, but in some extreme cultures, for being gay they throw people from the top of buildings in the name of God.”

“This is a Catholic country and I am a Christian. I believe in what Jesus said, but I am interested in what Buddha said, what Krishna said,” he answers, refusing to be drawn further.

“Yes, but what do you think…”

“I am interested in pagan life also,” he interrupts before I can finish my question, “here in Lithuania before Christianity arrived.”

“OK,” I submit. “Let’s talk about Carmen”

“Oh my God!” he says and a laugh from the others present signifies the huge weight bearing down on the mood has instantly dissipated. “Can I just go to the toilet, please?”

As Ten Walls disappears to the toilet, cigarettes are lit and the atmosphere returns to normal. When he reappears our company depart from the table and Mario and I are left alone to talk. About Carmen.

Before I leave the interview I know I am unsatisfied. I am unsatisfied with his answers, they show no sign of accepting responsibility nor of regret, unlike the second, English language apology issued on his Facebook page. I also feel unsatisfied with my questioning. Am I wrong to have pushed him so hard on such subjects? Has he not already apologized and accepted responsibility for his outburst? Is it necessary for an acknowledged Christian to be pro equal marriage and pro gay adoption in order for them not to be viewed as homophobic? Could it be that this was all a misunderstanding due to bad translation?

In the evening, after meeting Mario, I have the screen-shot of his initial Facebook post independently translated into English, sitting alongside the translator and going through each line, exploring every potential nuance of meaning. I also interview, via Skype, Latvian director and self-confessed liberal Māris Martinsons. He told me that he never heard anything negative regarding homosexuality from Mario during their work on what he admits was a controversial script.

“When I want to find the actors that act in this movie, ten actors said [to] me no. [They were] my friends. And ten said no. [After that,] when I talked to Mario about the story, I was positively surprised that he didn’t say anything about these themes.”

As its original translator Zabaraukas had already told me, the text of Mario’s Facebook rant turns out to be garbled, clearly the product of a mind off-kilter. It could be true what Mario claims. In no passage does he unequivocally link homosexuals with paedophiles.

The first video raises the subject of bestiality and it could be understood that it is they to whom Mario refers as “another breed.” The second video, which purportedly shows a violent beating, cannot be verified as it has since been removed from YouTube. The third video is a hidden camera sting that entraps a paedophile. Much of this ties in with Mario’s claims. Except one line. Without any error possible or doubt over meaning, using gross and graphic language, he asks, in the segment which relates to tolerance, how his friend would feel to learn his 16-year-old son had been on the receiving end of gay anal sex. Although his links had not been direct, he clearly had, within the broad scope of his near intelligible rant, linked homosexual acts with not only paedophilia but bestiality.

I register my dissatisfaction regarding the interview with the PR. She listens. She agrees that it had been uncomfortable in places. The next day I am granted, by text, more time with Mario, immediately prior to the evening’s performance of Carmen.

It is with an embrace that a bright and smiling Mario Basanov greets me outside the Compensa Theatre, less than one hour before the show begins. We walk to his car to speak in private. He is significantly less evasive with his answers today.

“Do you support gay people’s fight in Lithuania to have equal marriage?”

“Yes, I do. Why? Of course I do.”

“Do you support equal rights for adoption in Lithuania?”

“It’s enough for you to have a short answer? The answer is yes, I do.”

I explain I have had his Facebook post translated. I tell him there’s no mistake in the translation of the grossly worded question to his friend about his son receiving anal sex. I show him the text on my phone. He reads it aloud in Lithuanian and looks sheepishly at his wife who is sitting in front of us in the driver’s seat.

“Do you regret writing that part? Because that’s not about animals, Mario, that’s not about paedophiles. That’s about gay sex.”

“Yes, but I was talking about teenagers.”

“But the legal age of consent in Lithuania is 16.”

“18.”

“No, it’s 16.”

“When?”

“Yes, it’s 16,” says Mario’s wife. “That was the worst mistake Marijus made, because he truly believed it was 18.”

“My mama always said, Mario, you can drink alcohol if you want when you are 18 years old. When you are 16, we are taking care of you and it will be our trouble as parents. When you are 18, if you have trouble, it will be you that goes to talk to the police. So, 16 years old to me, I don’t want to say they are children, because to tell a teenager they are children is bad, but 16 years to me is a teenager. It’s not an adult man.”

“So you don’t have any problem with 18-year olds having gay sex?”

“Look, I just wrote in a very not nice way and this is for what I was apologizing. There are so many negative words I used. This is what I tried to apologize for.”

“So, out of everything you wrote, this is the part you regret the most?”

“Yes, of course. [When you showed me that] I really didn’t want to repeat those words. I used terrible words and I really apologize. It really wasn’t good. But, for me, 16 years old is not an adult.”

“Do you agree with an equal age of consent, for gay people and heterosexual people to have sex?”

“Try to ask me again in another way, I don’t understand.”

“If a boy can drink alcohol at 18 and a girl can also drink alcohol at 18, that is equal. So, if a heterosexual boy can legally have sex at 16, do you agree that a homosexual boy should also legally be able to have sex at 16?”

“Listen to what I will tell, we are human. We are the same. In my post, when I was talking about paedophiles, they are criminals. When we are talking about heterosexuals and homosexual people, we are all the same. We are the same and that is what I have always thought.”

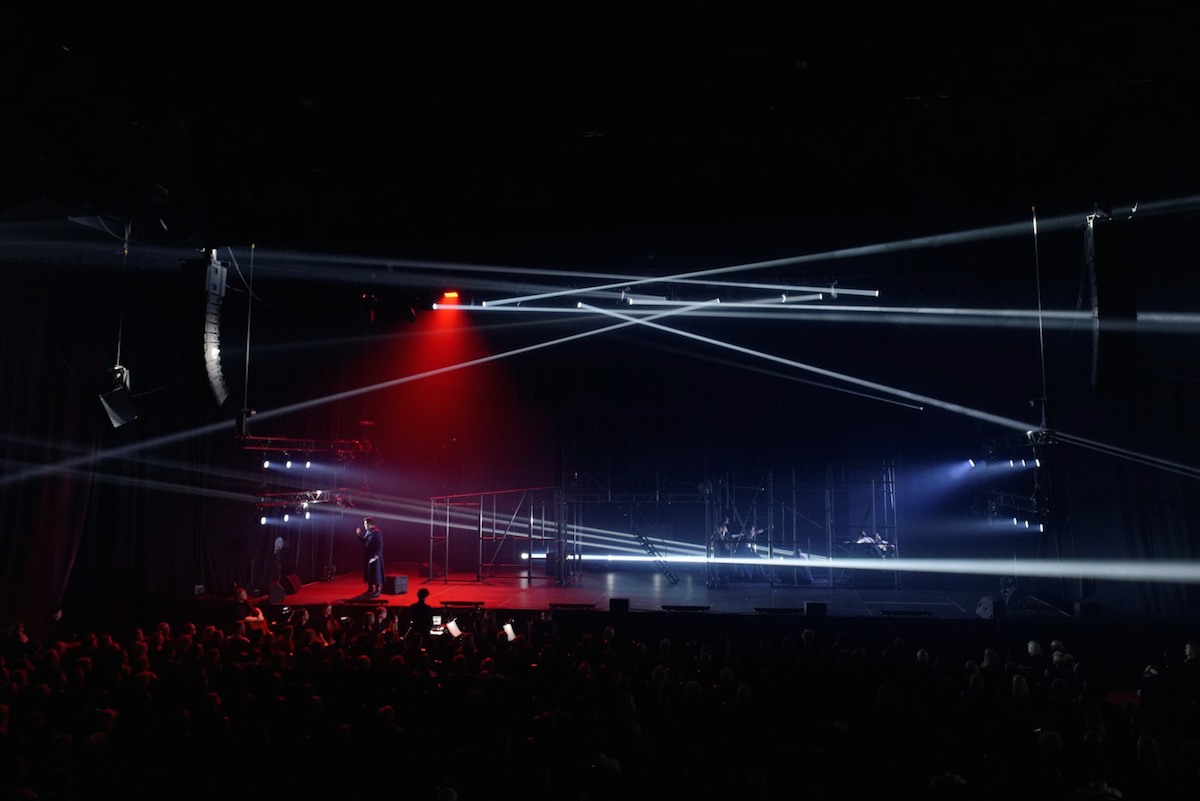

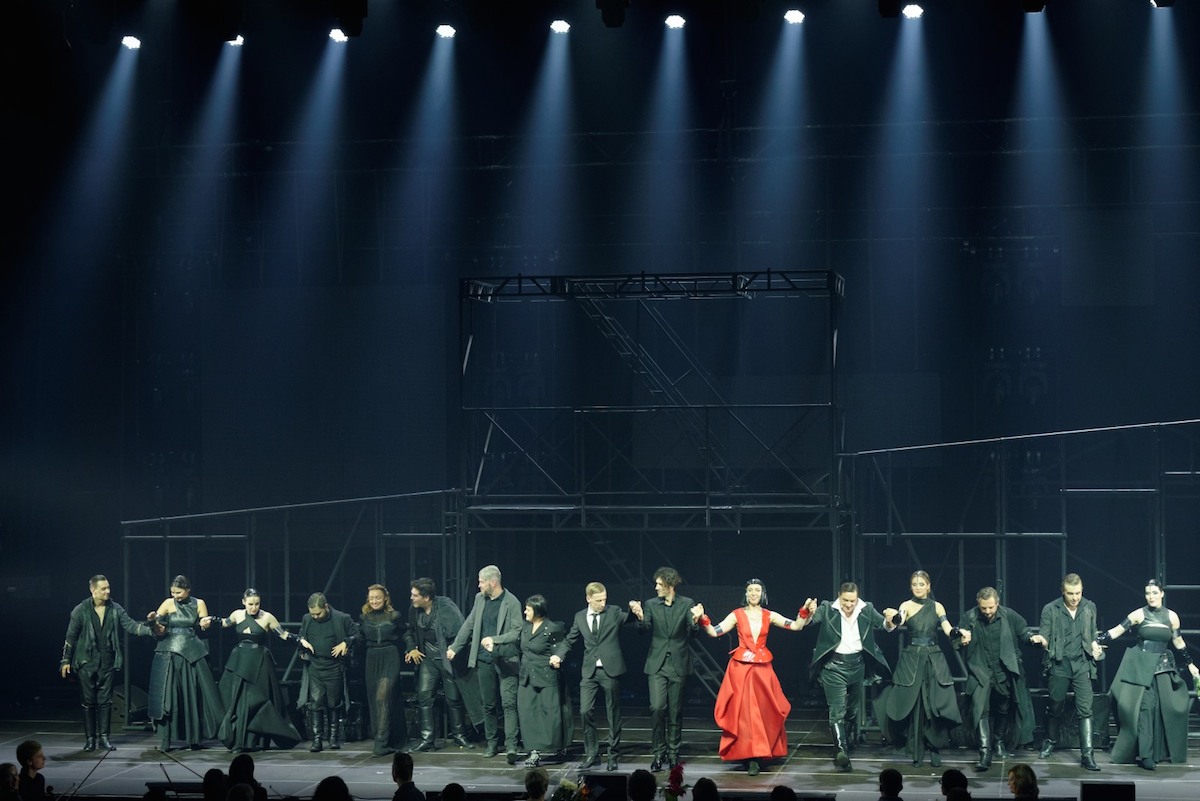

Every seat was taken in the 2,000+ capacity space at the debut of e-Carmen. It was my first visit to an opera, the medium being one I know nothing of. Members of the chorus invariably seem to do a lot of inexplicable hanging around on stage. Draped over parts of the ultra modern set, they are often merely voyeurs to the action taking place between the four main protagonists, who seem to frequently pace one way or the other wearing expressions of angst, the cause of which, given my sketchy remembrances of GCSE French, I can’t quite understand (I had anticipated the opera being in Italian).

But, the lighting is spectacular, as is the music Mario has made. Little of it sounds like Ten Walls, particularly in tempo. Instead, elements of trip-hop, at times a dark and brooding electronic pulse akin to Massive Attack, can be heard. His score is supplemented by a string section playing live atop who, at the end of the performance, join the director, Mario and the cast on stage to receive the audience’s gratitude. Holding hands with his collaborators under the lights, Mario smiles as he accepts the show of appreciation, the rapturous applause very short lived in comparison to the months he’s spent alone working on the music. If this brief acknowledgement were forevermore to be his sole reward, I have no doubt he would be compelled to continue his work. The music of the truly talented musician Mario Basanov is far from over.

In the days leading up to Carmen’s debut, over on the other side of Vilnius, the mural of Trump and Putin is restored on the side of Keulė Rūkė. Perhaps even more provocatively, this new version features the men holding each other and sharing a marijuana joint, the smoke passing from Trump’s lips to Putin’s in what is sometimes called a blow-back. Whether the wider dance music community will accept his apology and re-embrace Ten Walls so closely, only time will tell.

Carmen’s next performance is at Compensa, Vilnius on December 14.