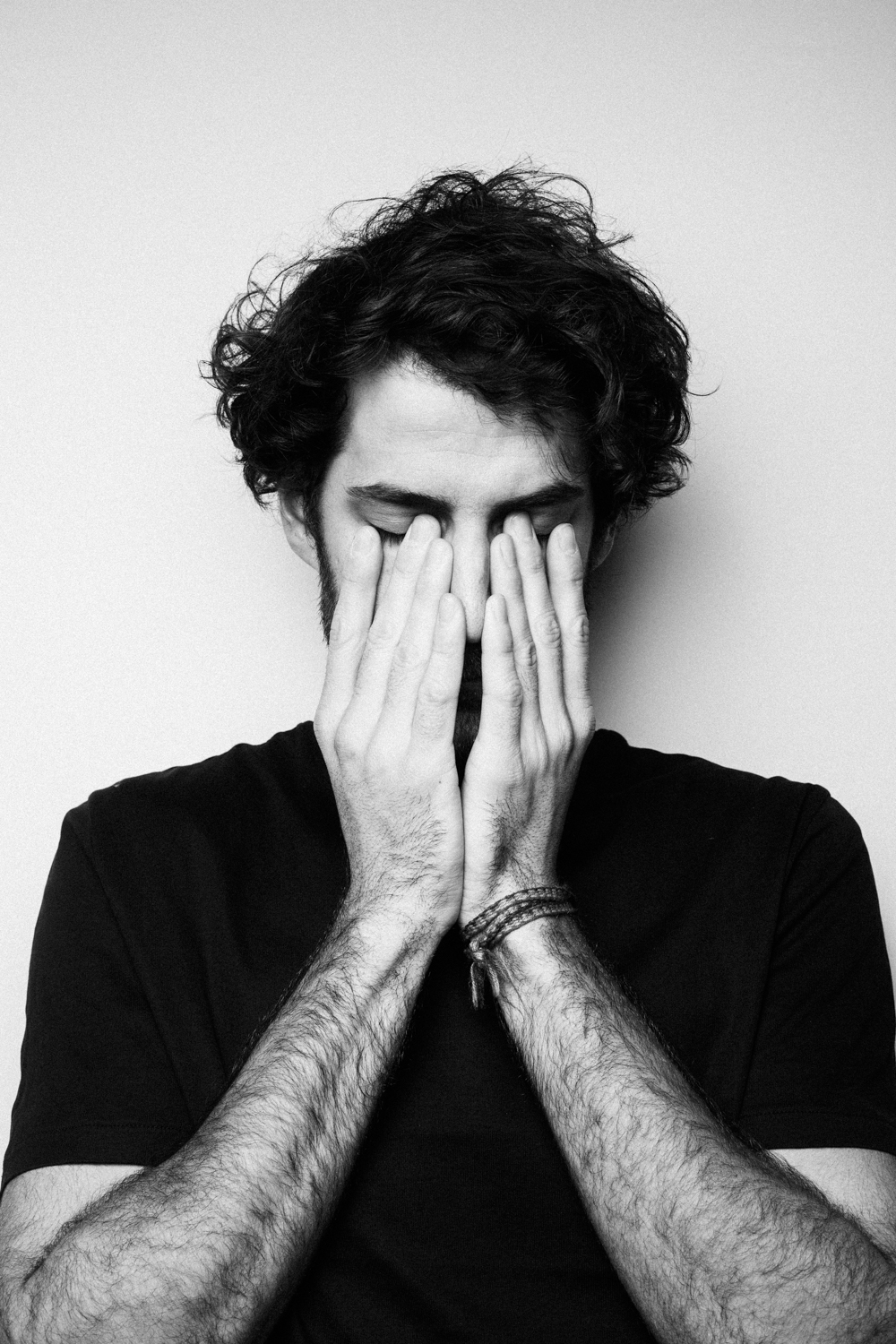

Lamache: The Fear of the Fear

The rising French DJ opens up on the anxiety that has held him back for so many years.

Lamache: The Fear of the Fear

The rising French DJ opens up on the anxiety that has held him back for so many years.

In 2012, things were “great” for Thibaut Machet. He was, after all, living in London with his beloved girlfriend, enjoying, too, a highly rewarding time on a professional front. Having had his talents recognized as by those behind Toi Toi, he had been installed as a resident of one of London’s most acclaimed event series and was beginning to tour more frequently than ever before. Great things, he says, were expected—by both him and those around him. And then anxiety struck, one night in Paris, changing things forever and hindering his personal and professional development for many years. “It’s completely changed the way I work and live,” Machet explains, clearly moved by conversation. Now, having spent over two years working to find a way to manage the condition, Machet is seemingly on the rise, freed, to a degree, from the mental shackles that held him back for so long. To learn more about the condition and the implications of it, William Ralston sat down with Machet at his Berlin home.

“I am tired of not being able to live like everybody. I am so conscious of how I am living and how lucky I am but this dark passenger takes over my mind. I see those people and friends enjoying so much. I wanna join them but I’m stuck in front of this wall.

It’s only when I sleep that I feel good. How shit is that.”— February 15, 2014. New York City

It’s a dark and cold Saturday evening in Kreuzberg, Berlin. Thibaut Machet, the 29-year-old DJ and founder of the Discobar label, is perched on a bright yellow stool in the middle of his bedroom, a colorful space that’s both spacious and immaculately maintained. “It’s about control,” he says, standing up take a sip of his beer before turning around to select another record from his sizeable collection. “I am always learning how to deal with it,” he continues. Then, as the needle drops and the punchy bassline comes in, he turns around the share a joke with a bunch of close friends from the city and beyond, laughing and smiling once again. He’s come a long way in the past three years. He’s come a long way since Manhattan.

Machet, better known as Lamache, is a rising member of a growing contingent of French DJs. Music, he explains, came into his life around the age of 16 when he began organizing his “Nochevieja” parties for around 50 people at his friends’ houses when their parents were away. “It was crazy,” he says. “We were so young and irresponsible.” Soon, aged 17, he taught himself to mix records and then began spinning at various bars around his hometown of Toulouse where he then earned a residency at one of the city’s gay clubs. “I never said I wanted to be a DJ, but it always felt so natural for me to play records,” he explains. “I just felt it.” Having completed his university degree in economics, he then moved to Paris in 2009, aged 20, to study sound engineering though intent on forging a career in music. “I made the mistake of doing sound engineering in order to be a DJ,” he says. “I thought that being able to produce would help me.”

From there, however, Machet’s career progressed. Immersed in Paris’ flourishing music scene at the time, he began exploring the city’s vast musical offerings, partying several times a week, only working or studying where necessary. “In Toulouse, I was stuck because I didn’t have the chance to see my favorite DJs,” he says. “But in Paris, I could see them every single weekend.” Over time, his reputation as an artist grew, in part down to a series of pre-parties that he organized where he would play alongside a number of local and international names when they were in town. It didn’t take long for him to catch the attention of Rex Club, one of the capital’s most widely know nightspots, where he began playing warm-up sets—and then Isis Salvaterra and Claus Voigtmann who subsequently brought him to London in 2012 as a resident of Toi Toi, one of the city’s most established underground event series. The brand now also encompasses both a label and the booking agency by which Machet was represented up until August 2016. Things, he says, were “great”: he was “blissfully happy” with his girlfriend at the time and his move across the channel was proving wonderfully beneficial for his professional aspirations. “These times [in London] were so intense,” he explains. “I was working all week and then traveling to gigs or partying every weekend without ever really thinking about the consequences,” he adds. “I was just like any normal kid.”

And then it all changed.

Returning to Paris in March 2013, just over one year after his move, Machet was scheduled to play an all night set at Malibu, an “amazing” club that has unfortunately now closed its doors. Indulging, somewhat, in another night of merrymaking with many of his close friends—and many of the associated accompaniments—he played until the early hours of the Sunday morning, carefree, focused and immensely content. “It was a real success,” Machet recalls. “I was on fire that night,” he reflects, smiling—but with a somber awareness, too, that this was the last time he’d feel so at ease in such an environment. Just a few hours later, now at home in a girl’s bed, he found himself struggling to breathe in the midst of what was later diagnosed as a “severe” panic attack—a moment that continues to have severe implications on his personal and professional life today. “I was very sad and scared of what was happening because up until that moment I didn’t know what a panic attack or anxiety really were,” he recalls. “I just thought I had had too much to drink, and so I tried to throw up—but I just needed to escape that moment. I needed to get away.” Only on home soil did the symptoms finally abate.

“I couldn’t travel to gigs because I couldn’t sit on a plane or go in taxis. I just could not leave my comfort zone—I couldn’t even go to the supermarket.”

Yet this was only the beginning—the spark, if you like. The next panic attack came the day after his return to London during a dinner with his girlfriend, to whom he had been unfaithful in Paris. “I had the same feeling—the same attack,” Machet recalls, clearly moved. “But this one came from nowhere, without alcohol or drugs, so I knew there was something seriously wrong with me.” From there, further attacks were interluded with periods of “great anxiety,” the severity of which made simply leaving his house nigh to impossible. “I couldn’t travel to gigs because I couldn’t sit on a plane or go in taxis,” Machet recalls. “I just could not leave my comfort zone—I couldn’t even go to the supermarket.” He actually missed two gigs due to panic attacks, one in a boarding lounge and the other on the train to the airport—where the trains stopped, triggering the condition. “I was so tense that they took me away,” he recalls. “It was extremely serious.”

The same pattern continued for a period of six months—during which he traveled if and when possible. It was, Machet explains, an extremely “dark and difficult period” during which he found great difficulty masking it from friends and seriously questioned his compatibility with the DJ lifestyle. “I was sad and scared of what was happening because I didn’t know what my body was trying to tell me,” he says. “I kept on asking myself whether the anxiety would go if I stopped traveling.” At times, he adds, he had to run out of artist dinners to find space alone, and he was also unable to play certain records because his anxiety was linked to the music. “There were certain thoughts, images or sounds that triggered the attacks,” he says. Depression, he continues, was present, too, in part due to his inability to properly communicate the condition with those around him. “They don’t understand,” he writes in a letter to himself in June of 2014, titled “Anxiety in America.” “Every day, this feeling is present present in my body and I try to guess or feel when it will go away,” he adds. “Every night I feel it coming back and I am scared of the night coming. I’m tired, but they don’t understand. They can never truly understand.”

Indeed, it’s difficult to understand the extent of his suffering without reading these letters—especially if you’re fortunate enough to not have fallen victim to such attacks. “I’m struggling to breathe. To eat. To drink water. It’s all a challenge,” he wrote in during a trip to New York. “I am living the American dream walking down the streets, looking by the window of this noisy taxi. But deep inside I’m drained by this constant dark pressure in my entire body, from the heart to the throat,” he continues. “Each record I play, each mix I do. This is not like before. I feel like a battery discharged becoming dark and lost,” he writes in another letter June 2014 during a gig in London. He describes anxiety like walking the wrong way up on a conveyor belt: “You’ll arrive there [at your destination] slowly but it’s more exhausting.” And there is plenty more material in this vein.

Breaking point followed soon thereafter, in Brescia, Italy. It was October 2014 and Machet was playing Disco Volante. Even upon arrival, he knew there was something “seriously wrong,” he explains. As Machet continues, “Everything was perfect. I was with my friends and I knew that everything was right in my life, but I was playing and I knew something was fucked—I was super sad.” A severe panic attack ensued, accompanied only with grave anxiety, forcing him to return to his hotel room alone—knowing something had to change. He called his booker and advised her to cancel “all upcoming gigs,” allowing for a two-month break during which he sought psychological support.

Guilt, of course, is certainly an ingredient in Machet’s condition; he was unfaithful on a loved one. But Machet feels that the roots of his difficulties run deeper than a drunken mistake in Paris. “Guilt,” he says, was the “trigger” rather than the cause. “It’s just a feeling that came one day and I cannot find why.” Exhaustion, however, also played an important role: forced to adapt to London’s high prices on arrival, he was working between 40–50 hours per week in a café; all other time was spent performing, record digging or producing. He was, he continues, also struggling with his relationship commitments and being “the only Frenchman in the [London] scene” at the time. “It was complete burnout,” he explains. “Anxiety is just a way of your body telling you that there is something wrong.”

Look a little deeper, too, and there is evidence of a predisposition. “My psychologists both say that the condition stems from something in my childhood,” he explains. “When you are a kid you are not conscious of everything but the implications will often be seen later in the life.” Reflecting back, he explains that his earlier years were not short of trauma: his parents divorced around his 13th birthday which caused him “great sadness.” Just three years later, one of his uncles committed suicide because he was “super depressed,” followed by his cousin who killed himself for similar reasons in the same place on the same day, 12 months later. He also lost his grandfather, with whom he was very close, at an early age. “My psychologist says that all this could have caused the anxiety,” Machet explains. “Some people know straight away but I am not sure if I’ll ever know for sure.”

“The anxiety comes from the fear of feeling anxious or having a panic attack. I get stuck in the loop. It’s the fear of the fear that gets me now.”

The condition, nonetheless, exists, albeit a more controlled and understood variant. At the time of writing, Machet’s most recent panic attack came just a few weeks ago in Perpignan, and they continue to occur “quite frequently,” he says. He refers to the condition, both in his letters—his “therapy,” he says. “I have to express what I feel”—and in our dialogue, as a “dark passenger.” “He [it] changed my life,” Machet explains. “As soon as I have a panic attack, I write about it and everything comes out dark—everything is wrong with me life. But I am not a depressive. It really is not me; it’s just someone else inside me.” Anxiety, too, remains, but in a different form. “The anxiety comes from the fear of feeling anxious or having a panic attack,” Machet explains. “I get stuck in the loop. It’s the fear of the fear that gets me now.”

Speaking generally, Machet explains that he has identified three triggers for his attacks: travel, restaurants, and “bad energy,” as he refers to it. “I don’t like being stuck in one place where I cannot move because if I have an attack then I will be ashamed,” he explains. “I am not scared of the plane or the restaurant: it’s just a social problem that’s linked to the shame of having one [a panic attack].” As for energies: he says he can “identify a bad energy” in a room or with people immediately and that this can cause the onset of an attack. It’s a given, therefore, that he will rarely play after-parties where “people are just doing lines and not focused on the music,” he says. “I have to avoid situations where I do not connect with the environment.” And this is just the start: “It’s completely changed the way I work and live,” he continues. “I always say to my friends that it’s better, but I just think that I have learned how to live with it,” he adds. “If you are not serious [with this condition] then you will never get over it.”

The most obvious of these changes is his attitude towards drink and drugs: Machet has long been immersed in a scene that is notoriously affiliated to alcohol and substance abuse, yet both have been absent from his life for over three years—barring the odd beer when he’s around friends. “I’ve had to become a lot more healthy,” he explains. “If I drink or do drugs then I become anxious, which is different to other people—and I am always scared of this.” Sleep, too, is fundamental in this self-preservation: rarely will he travel to or from a gig not having slept before; rather, flights and bookings will always allow for some time to rest before heading to the airport. “I know I must sleep a lot,” he says. “I used to take planes drunk after a night of partying, but I’m not strong enough now.”

Medication and various breathing exercises also play an important role—and have done since the early beginnings. He works with a psychologist and various healers on a weekly basis. By his side at all times are his Prazépam tablets, a short-term treatment for anxiety, and various homeopathic treatments. The former will always be taken before a day of travel or before a big dinner; it is, he says, the only way he can find any comfort in these situations.“I recently stopped feeling guilty for taking these [medications] as I understood that it was nothing bad to take them but just normal for my conditions.” And when these don’t suffice, he will resort to meditation and various breathing techniques as encouraged by his “healer. “I had “no confidence” but these techniques have allowed me to rediscover it because I know how to manage the condition.” It’s not uncommon, he adds, for him to spend time meditating in a restaurant toilet or in an airplane when his composure begins to wane.

For obvious reasons, bookings are carefully monitored, too. Working closely with his booker, Floriane Dubois—who is very “in touch” and “understanding” of the implications of the condition—he will carefully consider each request before any commitment. He expresses the importance of “properly communicating” with the promoter. “It’s important that they understand my condition so that measures can be taken to control it,” he says. “If I need a speedy boarding or more room then it’s because of the condition, not because I am a diva.” He tends also to play only for promoters who have been recommended by friends or for whom he has played before; “otherwise it is simply too risky,” he says. “I have to feel secure with and connected to their vibe.”

In conversations with Machet, it’s clear that he’s taken giant strides to the successful management of his condition. As he points out, there were times when he would have been unable to invite his friends over to his place for a beer; and that those times were not too long ago. And he is, by all accounts, happy within himself, laughing and joking with those close to him and clearly making the most of the time and space that Berlin offers to those who embrace it. Indeed, it’s almost impossible to fathom that such dark thoughts can invade a man with such a light-hearted nature; the only reminder is a vague vulnerability that is unlikely ever to truly dissipate. The condition has certainly left its mark.

“I miss going out and having fun with my friends. I miss having as much fun as the people I am having out with.”

And herein lies a certain sadness. While Machet says the condition has made him stronger as an individual, he reveals a real frustration and accepts that it does and will continue to limit him. “I miss going out and having fun with my friends. I miss having as much fun as the people I am having out with,” he says. It also hinders him, he says, professionally because the anxiety limits the amount of energy he can put into a set and he cannot travel as much as he would like it. It’s only this year that he’s been able to travel outside of Europe. “How did you want me to be myself and happy to live my life as a DJ when I have this dark passenger in my mind?” he adds.

Nonetheless, great progress is still being made. Discobar, a label that was launched when he was at his “lowest,” is finding much acclaim and Machet is now touring more frequently than ever, liberated, to an extent, from the mental shackles that held him back for so long. On the day after our interview, he sends a photo of him on the plane, expressing the pre-flight anxiety that lingers within; just a few days later he sent another photo of him smiling in front of the Egyptian pyramids.

“It was a long journey, but I’ve finally arrived,” said his message—and how true that would seem to be.