A Guide To: Virtual Reality and Music

XLR8R explores the rich intersection between electronic music and virtual reality.

A Guide To: Virtual Reality and Music

XLR8R explores the rich intersection between electronic music and virtual reality.

After a fitful start in the 1980s and 1990s, a new dawn of virtual reality (termed “VR”) is now finally upon us. By now, you’ve surely heard the hype; many consider it to be the “next computing platform,” following on from mobile phones and desktop computers before it. Regardless of whether VR ultimately becomes the dominant vehicle through which we interact with computers, it is fairly safe to assume that this rapidly developing technology will touch nearly every aspect of modern life in the coming years, from medicine and architecture to education and travel.

Music, too, looks to be a medium particularly well suited to VR’s particular brand of journeying. In many ways, electronic music is about building sonic landscapes for the ears, provoking the mind’s eye through various audio frequencies. The ability of VR to give these sonic landscapes virtual, though inhabitable, visual components is a powerful one; it’s not merely looking through the window as per a regular screen, but rather stepping directly through that window into an entirely different space.

For those entirely new to the medium, the logistics: Virtual reality, as promised by many science fiction writers, is experienced via a headset worn over the eyes and headphones over the ears. This seemingly simple combination of accessories effectively puts users “inside” virtual worlds inside which they can look around in any chosen direction. The best way to explain VR is that it feels like you’re somewhere else, where the “presence” conveyed by the experience is perhaps its most defining factor—that is to say, the extent to which it feels like you are, in fact, entirely submerged in that other place.

This most recent progression in virtual reality has brought ashore commercial headsets from Samsung and, more recently, HTC and Oculus. In addition to this, Sony‘s PlayStation VR is expected to land later this year. Using various cameras, lasers, accelerometers, HD screens, and other parts commodified by the mobile phone industry in recent years, the player’s head (and, with the appropriate controllers, their hands) are tracked in 3D space, giving them the ability to both look and move around inside these worlds, and interact with objects and characters inside them. This is neither 3D movies nor 5.1 surround sound; rather, it is a wildly, undeniably transformative new medium.

When it comes to music, VR can, for instance, be used to give players the experience of living inside music; as literal as being on stage with a virtual band, or as abstract as inhabiting a drum sound, perhaps, or seeing an impending bassline emerge in the form of an oncoming bullet train. Everything from album covers and music videos to laser light shows and psychedelics have extended the experience of music beyond purely listening; now, there is VR, meant to envelop the listener in private, audio-visual spaces.

With “desktop” VR experiences (i.e. those in which you are tethered to a PC that’s doing the heavy image processing) such as the HTC Vive and soon the Oculus Rift, you’re actually able to manipulate objects in virtual 3D space. This is performed using specially designed motion controllers, not unlike Nintendo’s Wii remotes, one in each hand. This is the entry point for creative input in VR, with a host of experiences designed to enable users to actually make music with virtual instruments inside virtual worlds. Again, this can take many forms—as literal as banging on virtual drums, or as abstract as throwing a handful of notes into a virtual whirlpool of synthesizer piranhas. The mind boggles at the potential applications for music creation.

In short, VR allows one to interact with computers in an entirely new way, and provides fertile new ground for how we consume and experience electronic music. We’ve taken the opportunity to highlight some of the most exciting early work being done to explore the intersection of music and virtual reality right now. Have a look and, by all means, have a go: Much like music, VR is a medium that must be experienced, not simply read about.

The Audio-Visual Funhouse: Playthings VR

As one-man studio Always & Forever Computer Entertainment, George Michael Brower’s Playthings VR is his first release in the new medium, following on from a series of fantastic audio-visual experiences designed for web, all which can be found here.

Brower’s latest work, Playthings, is billed as a musical virtual reality playground, and gives users the ability to play anything in their environment—including gummy bears, hamburgers, and any other ephemera.“The first time I held the Vive controllers, the first thing I wanted to do was use them like drumsticks,” Brower says.

To produce its interactive soundscape, Playthings sends MIDI data to external soft synths, which plays back musical sound inside the gameworld. Because of this, Brower isn’t actively sharing any demos of Playthings; he’s still working out some of the mechanics of the game to make it work for a home audience.

How did you initially start work on Playthings VR?

I was a programmer and designer working in advertising on the web before I got into VR, but everything I had done personally and professionally to that point had some element of interactive music. So I don’t really ever remember even “deciding” to do this project in particular. It was just very clearly, like, ‘This is the first thing George Michael Brower should do in Virtual Reality.’ I basically got started once the headset came into my proximity.”

“…you seem to actually be able to learn how to play instruments in VR the same way you learn an instrument in real life.”

What’s your favorite thing about the experience? Maybe a particular moment that you love watching people play?

Yes, I have lots of favorite things. Maybe number one is just watching adults lose decades of maturity. Some people really just become deaf to all warnings of nearby walls in the real world, start swinging their arms violently, laying on the ground, etc. The first time Playthings came out of my studio was for an installation at New York Fashion Week of all places, so watching these really beautiful, traditionally hoity-toity fashion folk acting like lil’ babies was really fun. It genuinely seems to make people happy for a period of 5-10 minutes, and of course that’s really cool to see.

The other thing that’s really surprised me is that you seem to actually be able to learn how to play instruments in VR the same way you learn an instrument in real life. I have a bunch of friends who are much more talented musicians than myself, and it has really impressed me how each one of them has made the thing sound both better than I can and completely different, all in their own ways. I know for sure that I’ve personally gotten much more precise, and feel comfortable playing melodies and even drums. I’ve had at least one jam session with a human in the real world while I played in VR, so I can’t wait to get some sort of multiplayer in.

How’d you go about making the experience musical? Did you create visual components and interactions, and then build music around them, or vice versa?

Sort of. I was primarily working in 2D before this, so I’ve been learning as I go, trying to create art I like within my technical capabilities. The whole thing started out with black and white cubes to test sending MIDI back and forth. I don’t really remember where the food came from—most of it got drawn on a visit to my family, none of whom have any VR gear.

So much of the art in Playthings was just a big rejection of realism, total escapist fantasy. I felt a sort of moral obligation to make as little sense as possible. The instruments were all created after the visual art in this case, operating principles being similar to the visual art: I want the sound design to be really tightly synesthetic, make things “sound how they look,” but always have some alien quality, trying to put together the familiar and surreal.

With the headsets coming out soon, any plans to release Plaything in any formal way?

There are plans! Playthings is showing at Tribeca Film Institute‘s Interactive Playground in mid-April, at which point I hope to have a distributable .exe that people with the Vive can download! I’m currently working on making the experience rely on a single computer, as opposed to one driving the headset and another driving the music.

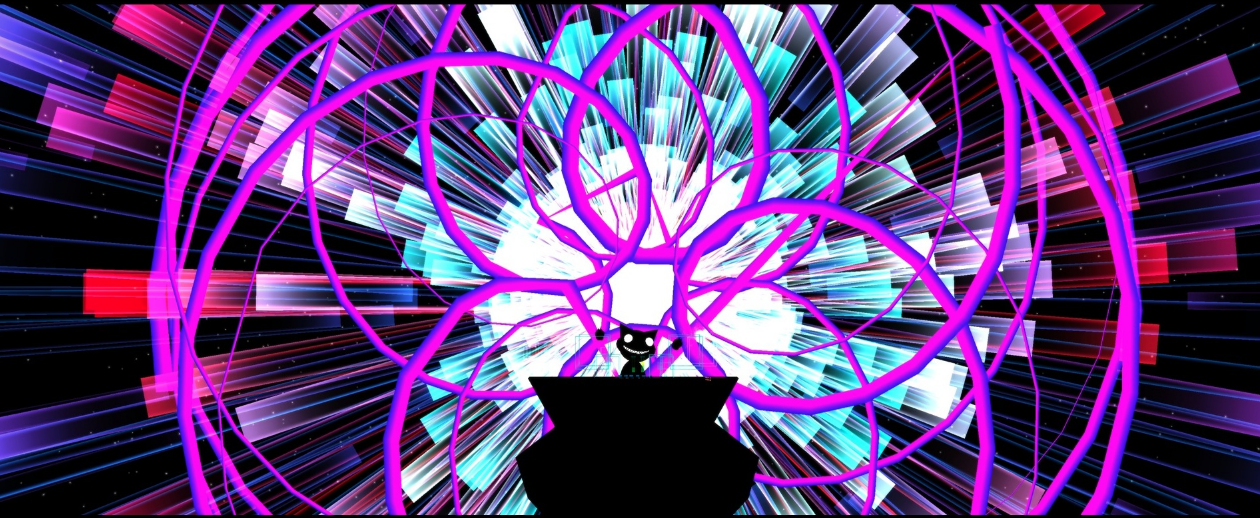

The Pyschedelic Music Space Shooter: “Rez Infinite” for PlayStationVR

The original “Rez,” which was released in 2001 for Sega’s Dreamcast and Sony’s PlayStation 2, was a seminal music game. Based on creator Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s exploration of the rare condition of synesthesia (whereby sensory inputs get their wires crossed enabling some people to actually see sound), the game’s vector graphics and shooter-informed gameplay were soundtracked by music from Keiichi Sugiyama, Ken Ishii, Oval, and Adam Freeland, among others.

Now, almost 15 years later, Mizuguchi has assembled a team to bring “Rez” to Sony’s upcoming PlayStation VR platform, in the form of “Rez Infinite.” “When I started working at Sega in the 1990s, VR was bulky, blurry, and slow,” Mizuguchi says. “It was clear the technology wasn’t ready yet, but even that small taste had me dreaming of what might someday be possible.”

With “Rez Infinite,” Mizuguchi says the game comes closest to what the team members saw in their heads when they were creating it: Vivid colors that blend seamlessly into one another, crystal-clear textures, and razor-sharp lines, with full 3D audio.

“I know to some people that’s all just a bunch of numbers and technical mumbo-jumbo—and in a way, I agree,” Mizuguchi says. “The only thing important about that technology for “Rez Infinite” is how it makes you feel; hopefully, it makes it easier to forget the fact that you’re sitting in front of a TV playing a game, and instead lets the real world melt away into a swirl of incredible sights and sounds that could only ever exist in your imagination.”

The Drum & Bass Rollercoaster: Squarepusher’s Stor Eiglass

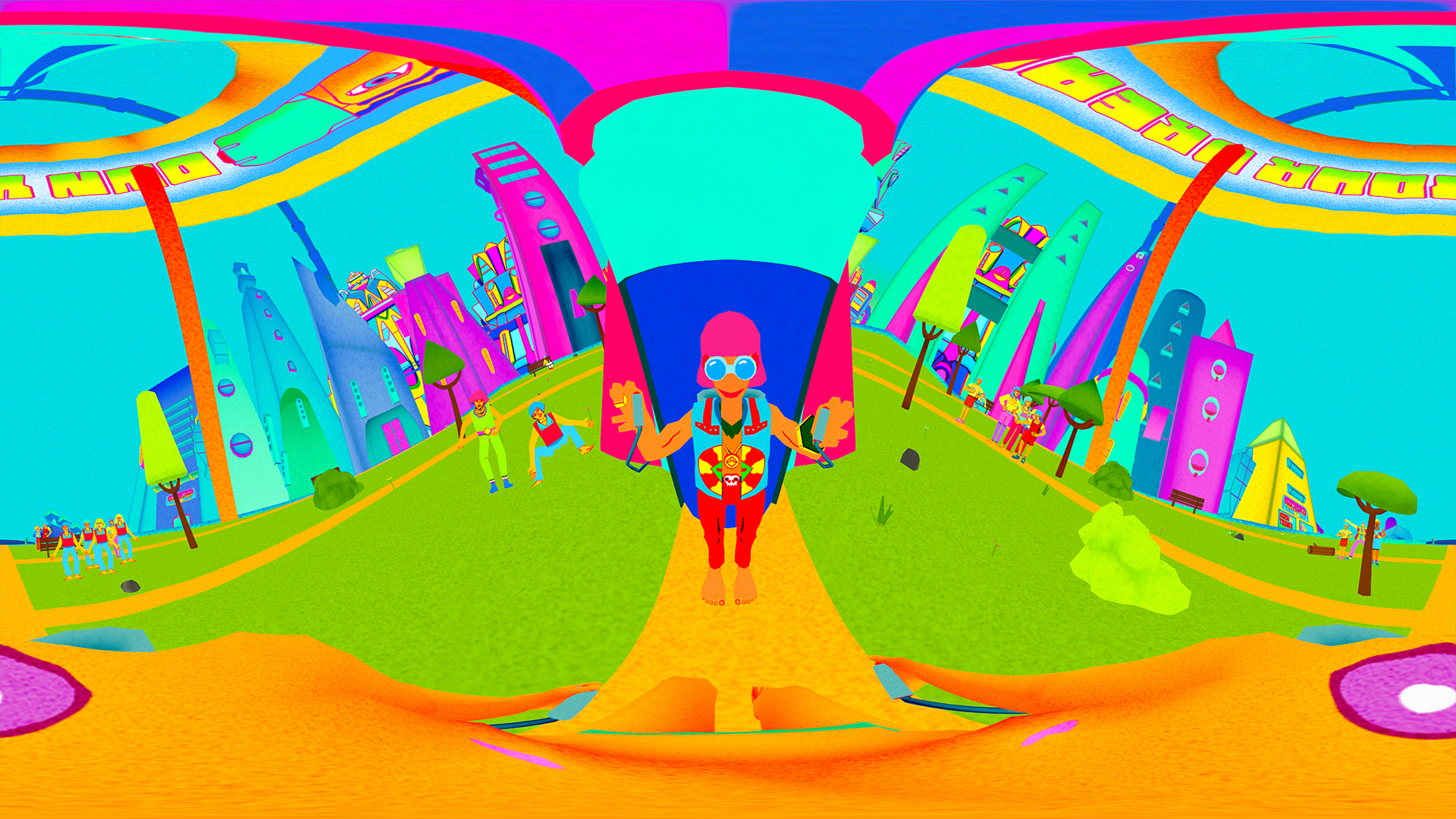

To mark the release of his most recent album Stor Eiglass, Squarepusher (a.k.a Tom Jenkinson) and Warp Records collaborated with London’s Marshmallow Laser Feast, Blue Zoo Animation Studio and illustrator Rob Pybus to create the label’s first virtual reality music video.

The result is a vivid, entrancing, maximalist rollercoaster of sight and sound that brings users to a hypercolor world full of weird characters and transcendental rabbit holes—all of which are tightly synched to Jenkinson’s music.

We spoke with director Robin McNicholas from Marshmellow Laser Feast about the project, which can currently be experienced via both Gear VR and Google Cardboard.

Did you specifically map certain kinds of sounds and patterns to certain visual ideas, or is it all pretty freeform?

Creating a music video in VR brings up tons of new challenges, and we’d planned to have lots more synchronized material—to some extent, this was limited by the render times and hardware capabilities. We animated dance moves and other objects distributed throughout the virtual city to different stems from the track. For example, the laser beams coming from the eyes in the mountain in the shaman scene definitely needed to be synched.

How did the idea for Stor Eiglass develop? Was the artist/art style something that was envisioned from the start?

There was a clear aesthetic goal from the start of the project, as we were collaborating with Rob Pybus, who has a very distinctive illustration style. However, what we found was the story took on a life of its own once we started to view it in VR. It was really good fun and one of those rare projects that had the whole studio super giddy.

What were some of the major hurdles that arose during development?

Mainly boring hurdles such as optimization and exporting cropped up. Authoring content for VR and 360º video is still in its infancy, and as a result quite fiddly. Other issues were definitely camera paths—we had loads of different approaches to camera moves—some of which really spun viewers out and made it pretty uncomfortable viewing.

Do you guys have plans for more VR projects, particularly of the musical variety?

Yes, we’ve got tons of plans for many VR projects—we’ve totally got the 360 bug. Also, music’s always a big and important part of our work, and we will continue to push for more sonic explorations in the future.

The Shapes and Sounds of VR Music Production: Lyra

Like “Rez,” Lyra explores the concept of synesthesia, but from the perspective of music creation. Based roughly on a traditional step-sequencer, users are able to manipulate notes much as they do in traditional music software—with the notable difference that they’re doing so inside a fully immersive 3D environment. As such, sequences can be of any length, the steps can be placed anywhere in 3D space, and the user can select the duration of the gaps between adjacent steps.

“More than 25 years worth of experience—first using PC-based, MIDI-only sequencers, and then DAW software and soft synths as those became available—led to Lyra VR,” says creator Jean Marais, who also has a history creating sequencers and synths for the Arduino platform.

Marais believes that having sound sources localized in space is what makes the experience so special. “Your perspective on the music you make changes as you move around,” he says. “Since you’re able to place notes anywhere in space, there’s also an unexpected sculptural aspect to Lyra—you’re free to arrange your music in any way that makes organizational, but also aesthetic sense. Lyra also makes it very easy to create sequences of varying lengths that loop over each other, creating interesting evolving textures.”

Indeed, creating music with Lyra feels quite literally like building a physical sculpture out of musical notes. “The visual aspect is definitely no afterthought,” he says. “We’re continually experimenting with ways to make the visual experience as interesting as possible—the visuals will continue to evolve, keeping our initial concept of synesthesia in mind.” The team plans to have a beta version of Lyra available on Steam this summer.

The Music Visualizer That You Sit Inside: Harmonix Music VR

Best known for its popular “Guitar Hero” and “Rock Band” games, Boston-based developer Harmonix has shown a taste of its first VR undertaking. Entitled (rather straightforwardly “Harmonix Music VR,” the project is essentially a music visualizer into which you can plug your own music.

“Old-school music visualizers are many and varied, but all of them were limited to a 2D screen and the use of real-time audio spectrum analysis,” says creative lead, Jon Carter. “With Harmonix Music VR, we have control over every aspect of your surroundings, using our internally developed, amazingly effective song analysis voodoo. We still use real-time data, but we can also look at the entire song, break it into sections, identify specific drum hits, and even categorize the feel of song sections to drive the visual and environmental transformations.”

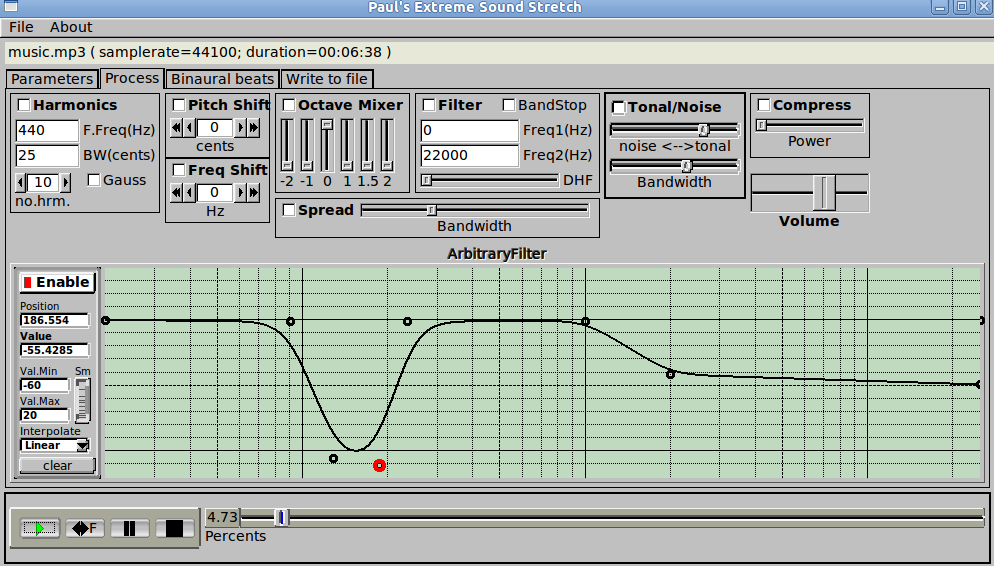

Notes From a Virtual Sequencer: Soundcape

Taking a different approach to music creation than Lyra, the upcoming Soundscape allows you to create electronic music in a futuristic environment, using huge virtual screens to add notes, change effects, and influence the characteristics of three discrete instruments. You can choose to do this alone, or jam along with two other randomly selected people online.

“Music, and specifically creating music via software, has always been a major interest of mine,” says Soundscape creator, Sander Sneek. “It started with FastTracker 2 and Cubase with VST plug-ins, and a MIDI controller 20 years ago.” Nowadays, Sander says he jams with Reason, Figure and Leap Motion’s Collider; as a creative coder and passionate music listener, he started to write his own audio software, and started recreating the mesmerizing ToneMatrix experiment from Andre Michelle in VR, using the gesture-based Leap Motion for input.

Soon he got the hang of it, and spent “way too much time” (his words) on implementing other instruments, nice environments, and optimizing the whole experience for mobile. “There are some features I want to implement in near-future versions, including a sampler, extra drum machine samples, and volume and BPM control,” Sneek says. “I’m also in early contact with the Amsterdam Symphony Orchestra to see if we can have a live performance in some way.”

The New Age of Sound Meditation: SoundSelf

When Robin Arnott first stumbled upon the idea for SoundSelf—his “virtual reality music meditation experience”—the Oculus Rift hadn’t yet hit Kickstarter. “VR as we know it existed privately between the brains of [Oculus founder] Palmer Luckey and anyone he cared to share his prototype with,” Arnott recalls. “[But] as soon as we started trying early builds on the early Oculus dev kits, it became clearer and clearer to me that SoundSelf and VR were meant for each other. With VR, the capacity of what we can do in terms of delivering a mind-altering experience is hugely amplified, and has justified a lot more development energy.”

Arnott says he thinks of SoundSelf as a psychedelic, or “technodelic” experience. Here’s the distinction, according to Arnott: “While both meditation and psychedelics are mind-altering technologies that allow us a glimpse beyond-the-veil, meditation gives the practitioner steadier and steadier grounding in what is real, while psychedelics are like a cannon that can blast you into a temporary experience of reality, but won’t help you build up the disciplined concentration for sober access to that space.”

What has surprised you most about developing SoundSelf for VR?

I don’t know where to begin! The design space of VR is so new. Everybody is making massive mistake mistakes. I think ten years from now we’ll look back at this era of VR development and the work will seem equal parts bold and quaint.

The thing with virtual reality is that we tend to think of it as giving us access to alternative realities that are different in content from the reality we know, but identical on a more fundamental level. You’re basically playing as an animal in space through time with stereoscopic vision. That’s not the game we’re making—that’s not what SoundSelf is. So designing an experience for VR that doesn’t have the same base assumptions of what the universe you’re entering is… has required a lot of experimental subversion of people’s expectations.

Head tracking is a great example. Rotational tracking makes tons of sense in most VR because you’re pretending to be an animal with a head. But we found that using typical head-tracking in SoundSelf made the abstract visualization feel like it was occupying space—which made it feel less abstract, more graspable, more familiar. That was unacceptable to us. So we had to try alternative head-tracking techniques that would meet people’s expectations for VR to track their head movements, but wouldn’t give our visuals a sense of being based in space. This was hard! The first “solution” we came up with incapacitated me with dizziness for literally hours after playing it for just a few minutes. But eventually we came across an idea that I think works really elegantly.

How’d you go about making the experience synesthetic? Did you create visual components and interactions and then build music around them, or vice versa?

It’s both. Visuals play into the sound, the sound plays into the visuals, and all of it originates from the player’s voice. That alone wouldn’t feel very synesthetic, but we’re pummeling the player with so much stimulus that they’re not as capable at making distinctions between “what I see” and “what I hear” as they usually are. All perception is sort of synesthetic anyway—more so in some people than others. So it’s more a matter of helping the player let go of their habit of writing distinctions and boundaries than anything else.

In the Club, Out the Club: TheWave

TheWave is the creation of Aaron Lemke, and allows artists to make music using virtual 3D interfaces. What makes it special is that it’s designed for groups: Other users can then join the session on any VR device, to experience the performance in a virtual networked, audio-reactive concert venue.

TheWave had its public debut at this year’s South by Southwest confernce. “The response was great—I think we definitely blew some minds,” Lemke says. “We learned that we had actually created the first cross-platform “co-presence” experience in VR, as the DJ was performing in the HTC Vive headset, and the audience members were passing around networked Gear VR headsets.”

Lemke sees a bright future for the overlap of music and VR. He says he can imagine cutting-edge dance clubs devoted entirely to VR, whereby the entire venue rigged with devices that track users in 3D space.

“You’ll put on a Gear VR headset when you walk in the door, and take it off when you leave,” says Lemke. He and his team demoed a small slice of this during this year’s Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, where they performed some of the first-ever live DJ sets in VR. “The performances were super fun, and we’re talking to lots of people about doing more of them,” he says. “That said, our main focus is to allow everyone to attend these shows virtually, without leaving their living rooms.”

The VR Album: Ash Koosha, I AKA I

Ash Koosha, who we’ve covered here on XLR8R, is among one of a few forward-thinking artists interested in bringing his music to virtual reality. We spoke with him about his plans for the medium, which will begin with a VR experience designed to accompany his recently released album, I AKA I.

What excites you in particular about bringing I AKA I to VR? Is there something specific to the album, or is it more of a general desire to pair physical and visual immersion with music?

Before I started making this record, I had a few experiences in VR at different exhibitions. I noticed how we are rapidly re-defining audio/visual content in a three-dimensional space. For years I struggled with explaining how my sound design (sound objects) have a physical and geometrical value, and always wished for a medium or a tool to translate the sound objects into visual objects; with VR, I’m thinking this can be made possible for the listener to not only hear the sound, but to see it and be there at the same time. The VR music experience can make everyone a synesthete.

How do you plan to organize “VR screenings” of the album? Will this be at venues alongside live performances by yourself?

Initially I would exhibit my single VR track and ultimately a full 20-minute version of I AKA I alongside my live shows. There will be headsets and headphones presented, and people can sit and experience being inside the composer’s head. I’m working with my friend, Hirad Sab, to develop the the experience on a webpage so everyone with a headset can experience it at home.

With VR headsets coming out soon, any plans to release the VR album in any formal way?

I think we’re at a point where the hardware is ahead of the content. This makes me even more excited about producing the VR experience and pushing the sonic and visual aspects of VR, but there are technical issues as well which makes the process a bit slow. I’m hoping to release a full version before end of this year.

What was your first experience with VR, or perhaps most formative?

One of the first experiences that stayed in my head was a long walk-through documentary about a photographer in a surreal space. It looked as if you entered a museum that didn’t (and could never) exist in reality. I like VR when it’s “virtual,” and not replicating places or objects that already exist in reality.

The Final Word:

The immersive potential of VR suggests that much more is set to come in the near future. Artists as diverse as Björk, The Grateful Dead, Run the Jewels, and (if rumors are to be believed) Radiohead have already jumped on the VR train; expect many more to show their cards in the months and years ahead.

Likewise, the tools for making electronic music seem ripe for innovation in this space, particularly given the physicality that motion controls naturally allow for. In much the way that our portable touch screens have ushered in a new era of music creation and composition tools, VR presents a new vernacular for how we’ll be able to bring musical ideas to life.

Whether the technology actually reaches mass adoption is beginning to seem like a less salient question than when it does; Samsung is essentially giving away Gear VR headsets to new buyers of its phones, and, although they’re more expensive (ranging from US$399 to US$799), higher-fidelity headsets from Oculus, Valve and Sony are all said to be taking a loss or making minimal profits on hardware in order to accelerate adoption. Brands, advertisers, data miners and pornography producers are already among those trying to control the virtual spaces we’re about to inhabit—as much as humanly possible, let’s make sure to fill those spaces with consciousness-expanding audio-visual experiences as well.