Artist Tips: Letherette

The Ninja Tune duo elaborate on the secrets behind their sample-heavy recording processes.

Artist Tips: Letherette

The Ninja Tune duo elaborate on the secrets behind their sample-heavy recording processes.

Letherette is the project of Richard Roberts and Andy Harber, two childhood friends so close that they are “more like brothers than anything else,” they say. The roots of their connection date back to one deep snowstorm one December—the worst since 1960, at the time—during which they were both born, so bad it was that ambulances were unable to transport their respective mothers to the nearby hospital. They then grew up just 30 minutes away from one another in Wolverhampton before crossing paths for the first time at the age of just 11 when they attended the same secondary school. Andy threatened to beat Rich up if he didn’t invite him to join a football game, and they took things from there—becoming close friends from that moment.

Both had musical experiences early in their lives: Andy loved guitar music, and had two older sisters and was “made” to sing along with them in the car; while Rich’s Dad has a massive soul collection. It wasn’t long until the duo began making music together, initially just hitting record and improvising for hours and hours. “We’d just smoke joints and indulge ourselves,” they say—and they also attended a school full of young electronic talent: Actress was two years above them, with Alex Nut in the same year. The latter introduced them to Bibio, and like him and Lee Gamble, they attended courses at Sonic Arts college.

And they’ve come a long way since then. First, they remixed Bibio’s “Lover’s Carvings” for his album The Apple and the Tooth, released on Warp in 2009, before releasing two EPs on Eglo Records subsidiary Ho Tep. In 2012, they contributed a remix to the vinyl version of Bonobo’s Black Sands Remixed album and released their debut LP on Ninja Tune the following year—and the label has since seen one more LP and several more EPs from the duo. Their latest album, Last Night On The Planet, dropped just last year.

Stylistically, their output is settled somewhere between hip-hop and French house—and the methods involve a heavy use of sampling, though incorporated with live instrumentation. In this month’s Artist Tips, we asked the duo to elaborate further on these sample-heavy processes.

Equipment

Sampling is my main sound source when making music, so any new ideas or technology that can influence or spark creativity are always a bonus. Learning the Akai MPC 2000, for me, was the blueprint of all sampling; and I still find all MPC’s and most of Akai’s rack samplers the most user-friendly and intuitive samplers in the game. I’ve also used and owned a Roland VP9000, Octatrack, Iris, Ableton simpler /sampler, Novation Circuit, Yamaha A3000/4000, Yamaha Su700, and so on. Also, some other odd VST granular samplers; including some Max For Live stuff I’ve made myself. Here’s a few tips, tricks, and techniques that I use when using samplers to make music.

Slicing

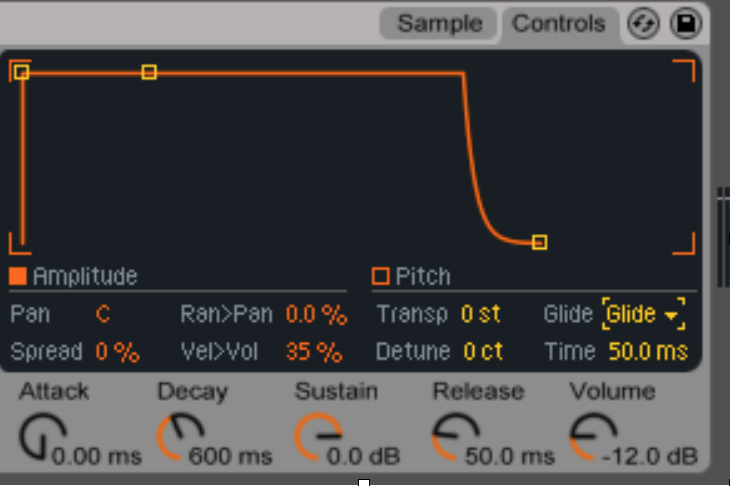

I mostly use Ableton’s Simpler or Sampler these days. Slicing audio to Sampler is very similar to the MPC style of sampling, adding samples to pads and triggering them. The new Simpler also has some great features. A little trick I like with Simpler is the “glide” feature, which allows you to play/pitch the sample as it plays, but without re-triggering the sample or changing the speed of the sample (time stretching). I used this a lot for the track “Dog Brush.”

Very similar to Roland’s elastic audio, you can, in essence, play a new melody with the music sampled. To take this process a step further, I often use the “Audio to MIDI” function—this can be found when right [control] clicking on an audio sample—which I’d consider to be a style of sampling, and extract the harmony or melodic content from an audio file and put it into MIDI notation. This can then be flipped/reversed etc. to create new chord progressions or melodies.

Process

I sometimes sample entire tracks to samplers like the Yamaha A3000 with the sample rate set to about 22k. The A3000 has a 22k (lo-fi) setting which is particularly nice; it rolls a lot of the high frequencies off but really beefs up the kick and bass. I used this process with the track “Shanel.” It was actually passed through the process twice.

It also works really well when you slow tracks right down and sample them, and then speed it up to the original speed. It’s a long-winded process but it definitely gives it a sound. I’ve even tried this in Ableton, where I slow a drum loop down to something silly like 40 BPM (originally being 120 BPM) and resample the slowed down drum track through a tape saturation plugin, render it, and then speed it up back up to its normal speed. It’s a process I used a lot with “Soulette”: I recorded parts of the track in from the cassette and then pitched whole parts down and resampled them. It always produces something a little odd and unexpected especially if you use it with effects.

Techniques

One of my favorite tricks to do on certain samplers is to “sample flip” samples while a loop is playing. For instance, you could have a different hi-hat sound for every triggered hi-hat, or have it change for one bar of every loop, or even a different clap/snare combination every other hit or loop. I used this in the track “Triosys,” recording loops and variations into Ableton and then arranging them together. I’ve also tried this with a range of scaled single notes and had the sampler randomly select the next note; sometimes it can produce unexpected patterns or melodies.

Another technique I like to do is using samples that have a few sounds in them like a small rhythmic loop or melodic pattern. When sequenced and slowed down or sped up they can create odd swing to sequences—it can also add a little life to a static sounding drum loop. I try not to be too anal about truncating samples as you can get some happy accidents this way.

Final Tip

I love using distortion on drums and samples, and I’m always looking for a new sound or way of processing it—whether using an old sampler and distorting its inputs, or using plugins that emulate tape or guitar amps. Nothing quite beats real tape distortion, especially if the tape is worn or a little damaged. I collect three-head tape machines for this purpose as its so quick to process samples from the computer to cassette and record it back in. Three-head tape decks have separate record and play heads so you can monitor from the tape in real time (slight delay depending on gap length between record and play head). Press play and record and switch monitor to tape and then drive the input until it peaks or you’re happy with the level of distortion, then obviously record this back into the computer.