Ask the Experts: Headless Horseman

The mysterious producer removes his veil for the first time to answer all your questions.

Ask the Experts: Headless Horseman

The mysterious producer removes his veil for the first time to answer all your questions.

It came as something of a surprise when Headless Horseman agreed to step in as our resident expert this September. It came as an even greater surprise when we entered his analog-heavy Berlin studio just last week and were greeted by a friendly, charismatic gentlemen—a stark contrast to the dark and enigmatic creature he has created as a vehicle for his growing catalog of acclaimed musical work.

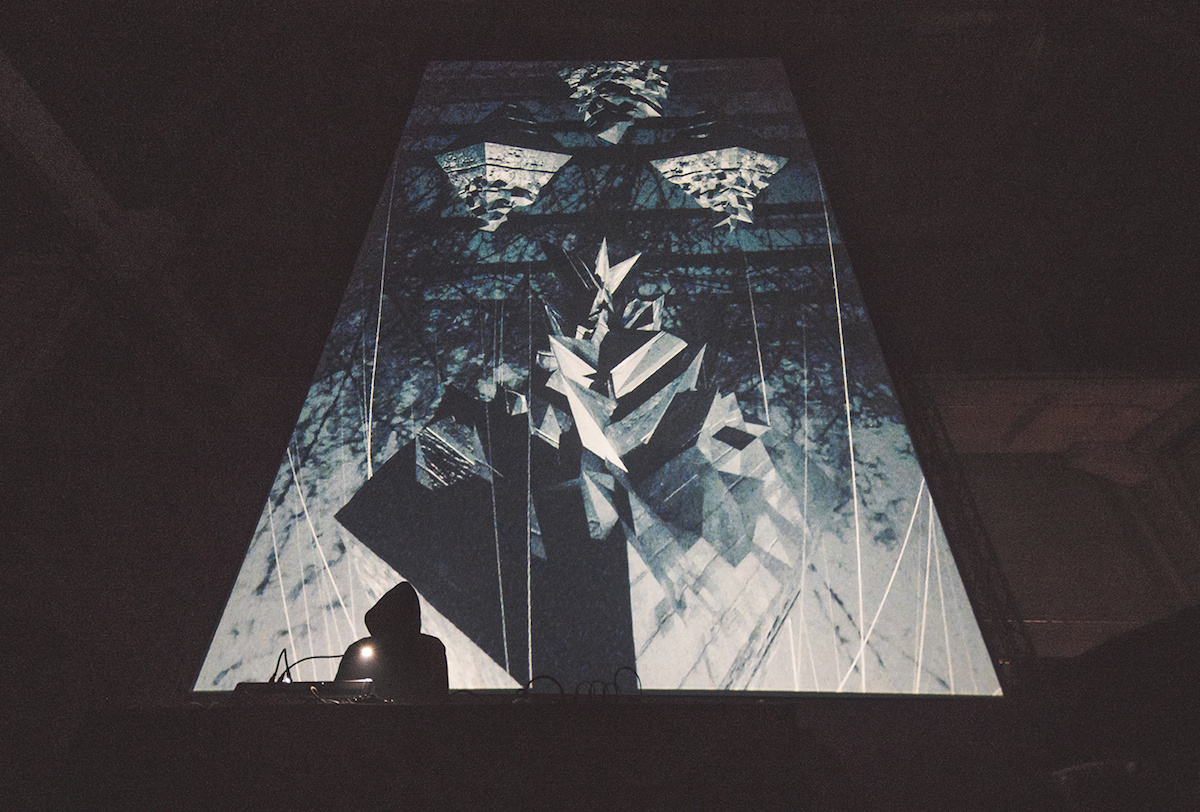

It is no exaggeration to say that Horseman is one of the most talked about techno artists at this given time. Indeed, there has been a shroud of excitement around the project ever since it surfaced with a with a stunning three-track white label in 2013, an interest only fuelled by last year’s full-length and 2014’s live performance at Berlin Atonal festival. Of course, there is no denying that much of this discussion stems from the ambiguity as to the individual behind it—but the real root of this infatuation lies in the considerable quality of the work. It’s a great honour to have him on board today.

Now, those of you who have read our previous editions of Ask the Experts will note that column was designed to get our favorite artists talking on subjects that they might typically not do otherwise. And this is most certainly true here: the confirmation of this particular piece of editorial was agreed on the premise that the man behind Horseman would remove the veil and speak candidly on record for the very first time. We wished not to speak with Horseman and prolong the mystery further; rather, we wished to converse with the enigmatic creator of this artistic vehicle, to better understand two simple things: how did he become this character and the current value of it. In addition to this, said artist also wished to respond to various more technical questions about both his live set and production techniques.

Consider this, therefore, not another perplexing conversation with a fictional character; instead, consider this to be the first interview with one of the scene’s most technically gifted artists, the content of which will unquestionably connect with both fans of his work and any aspiring artist who continues to struggle with certain aspects the creative processes.

For how long have you been riding?

I have been riding the musical path for roughly 20 years now. I started playing multiple instruments at an early age and then I continued during my teenage years. One Sunday afternoon, I was playing a matinee show and there were a bunch of DJs playing afterward. That was the first time I saw someone working a mixer—but I actually thought that they were creating the music on the spot. I really was clueless as to what they were really doing, but it was pretty much love at first sight.

I was working three jobs at the time and I saved up the little money that I had to buy some equipment. I had an old Macintosh computer—a Performa 637 and an Akai sampler. On this prehistoric setup I started to dive into the world of sampling. I started to go through my Mom and Dad’s old records and began to take little bits. I had zero idea of what I was doing. I wanted to mimic the sound of techno and drum & bass together, and this resulted in some of my early experiments.

“The Horseman is a mask of darkness that I require for my creative process in the physical, mental and spiritual sense. This disguised world has given me so much strength and power on many levels, not just personal.”

Back then—and still to this day, actually—I didn’t think about genres: I just wanted to make something interesting. If it sounded quirky then it made me happy. The goal has always been to push the music without any kind of boundaries. The technology, or the lack of it, didn’t really affect my creative processes. I just had to use what I had to make new sounds —and I guess the sampler was the easiest tool. Having done this for 20 years, my mindset hasn’t changed even though my instruments have.

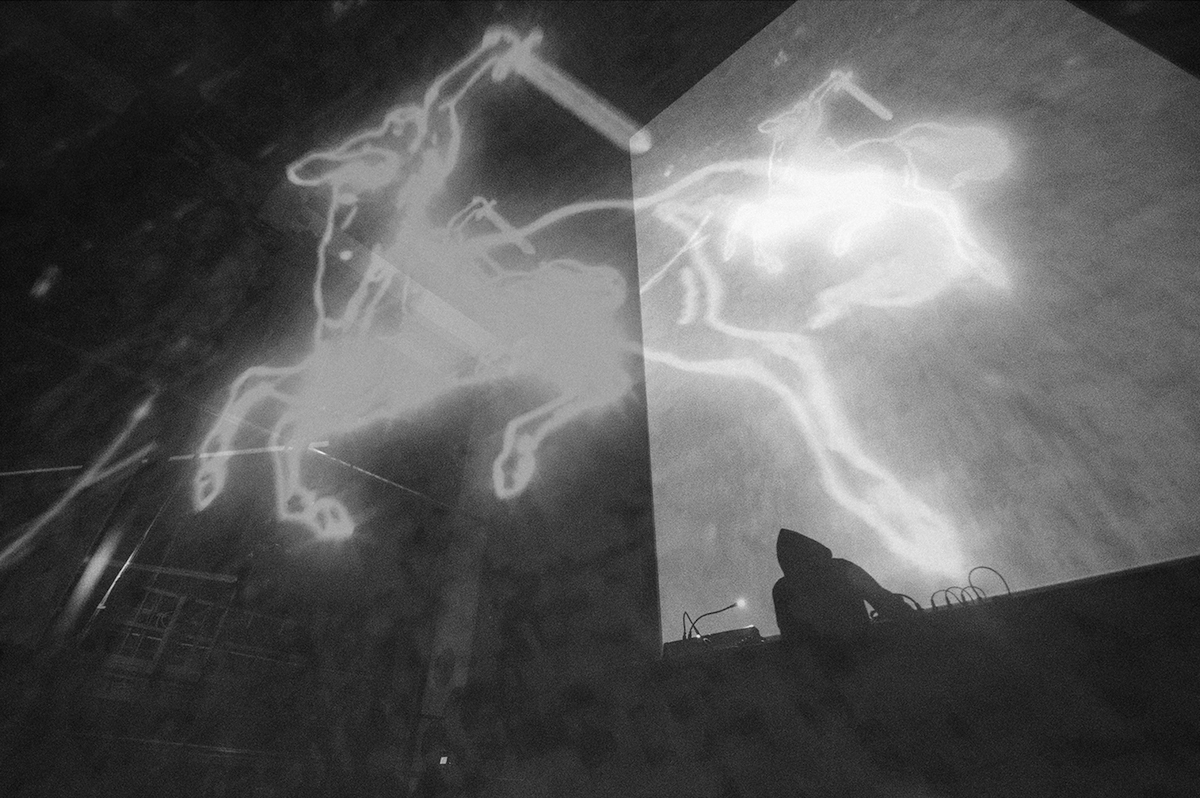

I have been riding as the Horseman for the last four years. It is a project that is inspired by all the events of my life; all these earlier experiences have removed all the creative blocks that I had—and also all those voices that told me that I had to do something or sound like something. I now have no real boundaries, and the result is the Horseman project. It is my masterpiece.

You seem very dark from you persona—but I met you at a show and you were very different to this character. Are you living in a parallel world?

The Horseman is a mask of darkness that I require for my creative process in the physical, mental and spiritual sense. This disguised world has given me so much strength and power on many levels, not just personal. I had a very hard time opening up and sharing my emotions when I was younger and let it all build up inside to the point where I felt trapped. I felt like I was locked behind a cast iron door with no key in sight. Creating music and a fantasy that surrounds it has allowed me to break free from these mentally damaging patterns.

When producing music, I need to be in complete solitude with zero distractions. And at the shows I still get anxious which makes it more difficult to be in the same trance; also there are lots of people around so it becomes harder for me to fall into this same headspace that is needed for me to create. Because of this, I am not really easy to reach on a verbal level until after they performance—but I am all ears after the adrenaline wears off. At this moment, and at any moment I am not producing, I am completely open to sharing this gift and talking with anyone. As an individual, I feel comfortable in my own skin. I see natural beauty in both dark or light things.

Do you have a musical education, or have you just developed your horsemanship by yourself over the years?

I started studying classical guitar at an early age. As much I loved the tones of it, I didn’t like practising: I wanted to play harder and more distorted music, like black metal, rock and grindcore. I always had a soft spot for the beauty of solitude after listening to classical music, although I was a horrible player—and I had the opportunity to go to a State University with a great music programme. For my entry audition I played some guitar and piano—but the selectors weren’t truly convinced.

“I never really began music to try to fit in or follow trends: I always did it first and foremost for myself. Any recognition or success was not important—and doing it for those aforementioned reasons would be wrong.”

They asked me what else I had been doing with music, and I was embarrassed to show them my early experiments on the electronic side. But they were actually quite impressed and then asked me how I had created the music. They thought my approach was so abstract and unprecedented that after a lengthy discussion they accepted me into the school. By my second year I had started to teach classes in MIDI and digital audio—at the age of just 19. I attended this school for four years but I spent little time in class because my professor believed in my talent. He made a deal with me: if I had an idea and felt inspired then I could skip class; but if I showed him the results and they weren’t good—if they showed that I had been slacking off—then he told me that he would come down hard on me. I also put out my first record in my second year of study.

At this juncture, I must also say that I was also very fortunate to have a crew of people—some of them visual artists, film makers and ballet dancers etc. There were artists of all disciplines. But we all fed off each other’s ideas, more or less. My musical education came more from the inspiration of these people and my professor rather than the actual classes. I learnt the most from being with people and seeing their efforts. From a technical perspective, my horsemanship has been developed all by myself. I am actually still in touch will all these people today.

Regarding your journey, did you ever have any difficulties? If you did fall off the horse, what made you stand up and jump back on again? Was it pure pleasure or an escape from reality? Or was it other reasons?

I never really began music to try to fit in or follow trends: I always did it first and foremost for myself. Any recognition or success was not important—and doing it for those aforementioned reasons would be wrong. I am more of a pessimist: I don’t expect things to work out, but when they do I have little bursts of happiness and this is more than enough in terms of “making it.”

Regarding riding as the Horseman, there were a couple of years where I had no desire to make music—or do anything with sound—because I went through the death of my father and a couple of close friends all in the space of just a few months. I just felt like hiding, and I had no motivation to be creative. I didn’t stop making music but I was lost in the clouds, until one day I was subconsciously able to turn my mind around and realize that I should not throw away the moments that make me happy—those which come through making music. I was then able to focus completely on the music and this acted as a healing tool for me. Instead of stopping, I stepped right in—and that came from turning myself into another character, almost like superhero; in this space nobody can touch me, I make the rules and there are no boundaries.

You don’t have to stop doing what you love when the events in your life bring you into the darkest hole. The best points in my creative life have come in the moments when I have had nothing—financially, in terms of friends, or anything. I felt worthless and I put all this negative energy into something positive: creativity. I had so much fire under me and that’s when you begin to create with these raw ideas that aren’t fine-tuned or polished. Those are the moments I remember. Being creative cannot fail you—it’s something you can always rely on.

How long did it take before you found your signature sound? By that I mean the point when you thought, “that’s it, I feel like this should be released.”

After the loss of hope for the reasons I mentioned above, I resurfaced and began recreating again. I then decided to begin using different tools and a different approach. I tried to create without rules. By doing that, the music was completely fresh to me and I had this whole new palette of sounds with which to paint. I had surprised myself and it was exciting to me to have something that sounded so new to me. All these years of trial and error, and all that I had absorbed from the world and its inspirations conglomerated into this collection of beats and sounds that will forever be evolving. The signature sound will never remain the same—but these developments happen organically. I try to make a conscious effort not to repeat myself with my music; for example; I try do start tracks in different ways using different tools in order not to repeat myself and ultimately become stagnated.

At what point did you acknowledge that you were ready to tackle the roads and present us with your message? Did you have feedback from people close to you, or just self-confidence?

I was always ready to tackle it because it’s something I have always wanted to do—but now there is an audience involved. I feel very blessed that I have the opportunity to display my art to an audience that is more than just two people. The first three Horseman records were made in just a few weeks, following the personal difficulties that I mentioned earlier—and these resulted from lot of raw energy and ideas. I never sought feedback from people close to me, and I didn’t foresee the success: the records just came out and I was surprised at how well they were received, especially given that there was no promotion. It gave me faith in humanity that people are actively searching for new things.

Do you think that it is possible today to make music just with a DAW on your computer?

Absolutely. The tools needed the make electronic music are the least important for a producer. There is a multitude of free plug-ins and software online, but I believe it is most important to sit down with someone in a studio to learn what they’re doing—this is perhaps the easiest way to learn how to produce music. All the gear in the world and the technical skills will never replace a good idea or the drive to create. I started with very prehistoric equipment; I had a very small setup with these ancient devices that did not have the capabilities of today’s equipment—but with all the knowledge I have now I would be able to return to this setup and obtain similar musical results.

How much time you need for a track usually, and how do you arrange it?

This is an interesting question. It really all depends. Sometimes I have a clear cut idea in my head for a chord progression or a sound, but I have no ability to get to a studio and then the idea can be gone altogether. On the other hand, you can get this concrete idea and you lay it down but it doesn’t move you as emotionally as it did when it first popped into your mind.

“I don’t feel like myself when I am making music. I get locked into a trance and the world around me becomes entirely irrelevant. Sitting alone when I am in the headspace gives me these moments of pure bliss where I don’t even think about what’s going on around me; where I don’t have to think about the hustle of bustle of daily life.”

For the actual time frame, it really all depends: sometimes you have a day where the track is done in a matter of hours—where the emotion is raw and the track doesn’t need too much fine-tuning. In other cases, I can get really obsessive on small sound design properties of elements and I can spend months going back and forth trying to find the solution—and then I have trouble wrapping it up and finding contentment in the end result. In these cases, it’s easy to overwork the sound element and ruin it; you actually end up losing the initial idea altogether. From experience, the tracks I spend too much time working on can often end up feeling stale. They might sound clean from the production standpoint, but the “punk” is gone. They aren’t abstract; they sound too well drawn out.

When conceptualizing a track, how much does your persona that you have created come into play? Are there specific stories that go through your mind that you try to express through techno? And if so, how do you usually translate that into a song format?

As I mentioned earlier, creating this character puts my mind into the body of a totally different person. In this character, I have no rules for creation: I don’t feel like myself when I am making music. I get locked into a trance and the world around me becomes entirely irrelevant. Sitting alone when I am in the headspace gives me these moments of pure bliss where I don’t even think about what’s going on around me; where I don’t have to think about the hustle of bustle of daily life. Daily struggles—the difficulties of every day—can often pollute the creative headspace and prevent you from producing your best work. But by transforming into this character on a subconscious level I can start with a clean slate and begin creating with no expectations or worries—and this is when the finest work is done.

However, I cannot just turn ‘on’ this character. I cannot become this Horseman straight away. I might see something or be somewhere, and a certain sound or image will then trigger an emotion or an idea. All of a sudden I turn into this character and enter this trance—and only then can I begin producing. These triggers come from all around. And also when I write ideas—or blurbs—these might trigger a fantasy which I can then visualize. I can then picture a soundtrack to this fantasy and then I have to hope that I can reach an outlet to release this moment before it has gone forever.

I would like to know from a technical standpoint, how do you maintain that killer rolling groove on your tracks? They sound so organic and compact.

The groove element and compactness come from the arrangement and choice of sounds that I use more that anything else. I think the key to the creation of a “rolling” feel is the use of a multitude of sounds that mimic one another in a pattern. It’s about completing the puzzle so that the frequencies complement one another—but without clashing. Lots of the groove breathes in the low end. I tend to use three or four kick drums in a loop, so I am alternating between more punchy kicks that exist in the mid-frequency range and others that exist in the lower/sub range.

I also tend to nudge notes around the grid plus/minus fractions of seconds, as well as inputting notes by hand with the quantize setting completely off, so all of the sounds are not hard quantized to the grid.

“Remember this: the gear and your software wants you to push it, and miscalculations can result in beautiful overtones.”

As much as the low end is important for groove, the same theory applies for sounds in the higher register. If a snare was happening on the 2 and 4, it is easy to give it some lift by loosely layering it with another sound (i.e. a clap but it’s slightly nudged off the grid to give a flam sounding effect). If you adjust the volume of these two sounds throughout the entire duration of the track you continue to implement a more human touch. All in all, simple variations create the illusion that the same samples re-occur in a repetitive fashion, but a more human feel has now been implemented.

The organic feeling and compactness is a direct result of the mix down—but this is a very lengthy topic to speak about technically. In short, I separate every sound on its own channel and treat with EQ, compression and limiting.

Modulating effects also help to escape the static-sounding dilemma. For example, if there is a sustained string playing through the track, I might slowly adjust both the reverb time and amount, and the delay time and amount over its entire duration to give this stale string section a little bit of movement—so it swirls around in the stereo image and tells its own nice little story. Layer that same string patch an octave lower but invert your adjustments on the new layer. The result is an atmosphere that is quite spacious and beautiful.

Remember this: the gear and your software wants you to push it, and miscalculations can result in beautiful overtones. If you spend time learning what your hardware/plug ins are capable of then you’ll be adjusting the settings in no time and get very close to what you want to hear long before you’ve hit the play button. I still learn new things every single time that I sit down to create and I feel the possibilities are endless. Techno doesn’t need to abide by the rules and this is what keeps it exciting.

CLICK A PHOTO TO ENLARGE AND VIEW GALLERY

What’s the ratio of samples you find / field recordings you use in tracks?

I actually don’t use any field recordings. Everything is 100% synthesized. But this probably is not too obvious because in my sound design efforts I may use multiple different layers to cover the wider range of a sound and ensure that it doesn’t come out too synthetic. For example, sometimes I will record six different variations of a synth or pad to fill the sound up, ensuring that it has all the characteristics of melody, atmosphere, overtones, noise and harmonics.

However, I do spend a lot of time outside recording the sounds of nature—but I feel that their natural beauty is so strong that I would ruin them if I incorporated them into music that involves so many manmade objects. None of the field recordings I have made have been included in any of my work to date, but I have a nice library of sounds and textures—and I will frequently listen to them to calm my nerves.

How do you organize your live sets? Is everything carefully prepared? Do you write patterns live?

I like to refer to my live sets as “random controlled chaos.” I use two Octatracks in the show because this gives me more physical analog outputs to the mixing board. The first Octatrack is loaded with percussive sounds and pre-prepared beats.

The second Octatrack is loaded with clips that I trigger on the fly during the show. These clips are anything from drones, noise and backbeats, to stems cut from my own works that I use to re-create my releases with an added element of the other machines singing on top. This Octatrack only has blank triggers loaded so no sound will come out until I decide what to load while the set is running. I also tend to have bits of ideas from the previous studio week loaded onto the memory. It’s a nice test to see if a few new patterns speak freely with the rest of the setup and interesting to feel the reaction from the crowd. The Octatrack is a very powerful machine that also allows for some quick and intense mangling of samples on the fly.

“As I’m a hands on person, I really find pleasure in having a wide array of parameters, knobs and faders to freely modify so I can cover the complete audible spectrum.”

The Octatracks also have an onboard MIDI sequencer. I have MIDI out enabled to a Dave Smith Tetra or Access Virus (depending on what I bring out) and the MIDI sequences are written live. There is also an Elektron Analog Four in the setup which has patterns pre-programmed, but each of the four voices are quickly and easily sonically modifiable in the live situation. It is also simple to add/remove notes as well as re-write sequences on this device while its running.

Every output of each piece of gear is singularly separated on the mixing console for complete control and flexibility. It’s like having a stack of turntables. I tend to also run a few guitar pedals for some extra reverb and delay as well as a portable compressor for one stereo pair of drums from the first Octatrack just to keep the backbeats levelled.

Basically, it’s a powerful small setup that allows for a lot of improvisation and quick decision making. As I’m a hands on person, I really find pleasure in having a wide array of parameters, knobs and faders to freely modify so I can cover the complete audible spectrum.

You are a fervent user of Elektron gear, and I would like to know if you could give us some insights about mixing them, live, studio. I own some and I struggle with the internal mixing, I think it’s a weak point of their machines. So how does it works for you?

Both in the live performance and in the studio, I mix all of the machines on a mixing desk—and I consciously connect like-minded sounds to their own faders/channels. I would have to disagree that the internal mixing is a “weak point,” although I do understand if you are referring to the accessibility of level controls.

I am not sure what you have for gear, but the Octatrack, for example, has an easily accessible volume control as well as the parameter lock feature which allows for manual adjustments to notes entered on the sequences. If you are running the units into one another and not using an external mixer, I would think it would be best to take time to level out all of the samples on the editor. This won’t take you long, and you’ll avoid those spikes in volume that always occur when jamming or recording.

When playing live, I tend to have the internal DJ EQ effect loaded on every track. By using the push encoders you can quickly cut or boost certain frequencies—but as I mentioned early, I utilize all physical outputs on all my machines so I’m able to mix live on a mixing console.

Coming up with a workflow with your gear takes time and I suggest that you put in a few more hours to see what works best for you. If you prefer having a set of faders then any MIDI controller can be assigned to any parameter of your units and this could bypass the need for having a mixing desk.

What distortion effects modules do you prefer?

I don’t normally use any dedicated distortion units—but I achieve saturation, gain and overdrive by utilising EQ and compression. This actually looks like it is going to change now as I’ve had the luxury of obtaining Elektron’s new Analog Heat. In little time, it has proved to be an exciting way to get creative with distortion in a modern fashion. This box is already getting a lot of airtime in the studio. I plan on incorporating it into the live setup as most of the controls have dedicated knobs so it’s real easy to use and loads of fun to jam with.