B2B: Robert Hood and John Tejada, Part Two

Yesterday, we featured Part One of our extended conversation with Robert Hood and John Tejada—two […]

B2B: Robert Hood and John Tejada, Part Two

Yesterday, we featured Part One of our extended conversation with Robert Hood and John Tejada—two […]

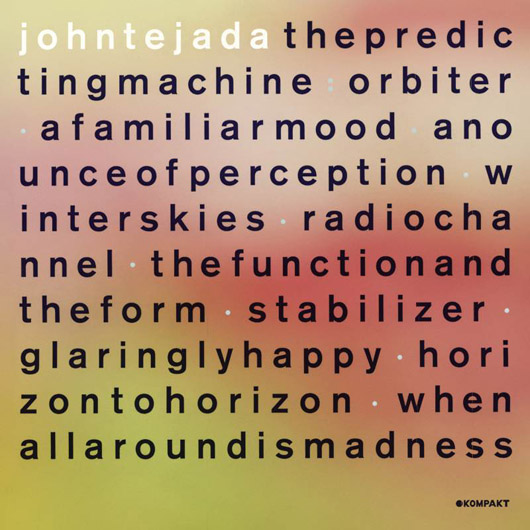

Yesterday, we featured Part One of our extended conversation with Robert Hood and John Tejada—two verteran producers who have recently added new full-lengths to their accomplished discographies. In the second chapter of our three-part conversation, we discuss their perspective on the American techno legacy and each man’s approach for their respective new albums.

XLR8R: Given that both of you have seen a lot of the rises and falls of techno in America, what do you make of the US’ techno legacy? Do you think your music has been better received overseas than in your own country?

John Tejada: On the West Coast when I started out, there was a big scene but it wasn’t the same thing that I was into. I would be really hungry though, and I’d go to the record shops and pick up magazines and all that. It was a shame, because there was so much domestic music I didn’t find out about until much later because people were just ordering imports. You’d see a lot of stuff on R&S, which was cool because they were picking up on Detroit artists and labels, but at some point, you would realize it was all being made in the States—that was a big realization. I guess the point I’m making is that US artists weren’t readily available here. You’d see big Detroit releases come through as an import once a European label had licensed it. That was how I was exposed to some of those seminal releases, and I think it took a really long time for people to start getting and supporting domestic music.

Robert Hood: I can remember back when Detroit was progressive and people got it. As far as Detroit embracing electronic sounds, I can remember right before Mojo went off the air, he was embracing techno and house so much more, it was starting to become a phenomenon. But radio programmers weren’t sure how this would fit into their programming. You don’t just go and play A Guy Called Gerald in the middle of a top-40 set that includes Mariah Carey and Luther Vandross. Aside from that, you had the sub-culture, places like the Music Institute and the UN that played underground house music. You had DJs like Ray Berry and Terrence Parker, who used to play a lot of the social club parties and spin these austere imports along with Detroit, Chicago, and New York stuff to a few hundred people. Then the scene began to split—the gangster types listened to nothing but Too Short and NWA, and the preppies listened to house music and techno from Metroplex and Transmat. So, as hip-hop became more prominent on the radio, techno went further underground. And then artists started going to Europe and becoming more and more successful and playing to more and more people. As artists, we should have not just gone to Europe to play to people that appreciated the music, but we should have tried to cultivate our own backyard as well. That drive for success was fine, but at the same time, you have to take care of your scene, take care of your home. But what’s done is done.

XLR8R: Robert, you live in Alabama now, but would you say that Detroit still plays a role in your music? Your new record was inspired in part by a documentary about the city, right?

RH: The album was inspired by a documentary called Requiem for Detroit. It talks about black people coming from places like Alabama and heading to Detroit in search of a better life working in the auto industry and the adversities and racism they faced along the way, as well as the decay—the social decay, the economic decay, the unemployment—that Detroit has faced and is still facing. I no longer live in Detroit, but I am Detroit. I could live on the East Coast or the West Coast, I could live in Europe or I could live on the moon, but I’m still Detroit. It’s still in me. Those streets raised me and the experiences I had there shaped me. My grandfather worked for Chrysler, my father-in-law worked for General Motors, my step-father worked for Cadillac, and the Motown sound and all of that shaped me growing up on the streets of Detroit—dealing with racism, dealing with gangs, dealing with unemployment, racist cops, and just trying to survive. So that feeling of facing adversity and facing challenges, and overcoming those adversities all plays a part in the album.

XLR8R: And John, what was your process in approaching your newest album?

JT: Usually, when I’m working on a full-length, it starts to come together by accident. I’ll have a more intense flow of creativity and I’ll end up with a handful of ideas or finished songs that sort of accumulated and follow the same theme. And when that happens, I kind of click on and realize I’ve got something that could turn into a full-length. I’ll experiment with things to see if I can continue in that direction, and if that works out, I’m on my way to doing another album.

XLR8R: And how do you identify one of these themes?

JT: It’s a little bit hard to put into words, but they all just sort of fit together. One is a continuation of another, but maybe a different type of rhythm. Then it just starts to feel like a complete idea, and I try to see if I can make more songs work in the same realm, while still varying in style and feel.

XLR8R: Was your process for your album similar, Robert, in the sense that you experimented until you found a theme? Or were there specific images and such from the film that led you to make the tracks?

RH: The dialogue in the movie as the interviewer talked to different people about their experiences growing up in Detroit and the politics of Detroit, as well as the pictures I have in my head about Detroit and about the world, about mankind, about how people treat one another—all of those play a part in the music. And I guess for me, it’s all about: “What am I trying to say? What am I trying to do? Am I trying to get people to dance or think about something, or am I trying to take the listener to another place?” I do experiment, and a lot of times, I will start with the drums and build everything around them. That decides how everything will go and as I’m building, I’ll think about, “What is this saying?” or “Where is this taking me?” Once it begins to materialize and as the clay begins to take shape, I try to see what is coming to life here and what direction it’s heading in. Once I develop a better idea, the whole paragraph starts to form into a book—chapter by chapter—and the story starts to form. That’s how I work.

Click here for part one of B2B: Robert Hood and John Tejada. The final conclusion will be published tomorrow.