Battle Cats: From the rise of house in the ’80s to today’s juke and footwork scenes, Chicago’s circle keeps expanding

“It’s so fucking hot in here!” is the cry heard from almost everybody in the […]

Battle Cats: From the rise of house in the ’80s to today’s juke and footwork scenes, Chicago’s circle keeps expanding

“It’s so fucking hot in here!” is the cry heard from almost everybody in the […]

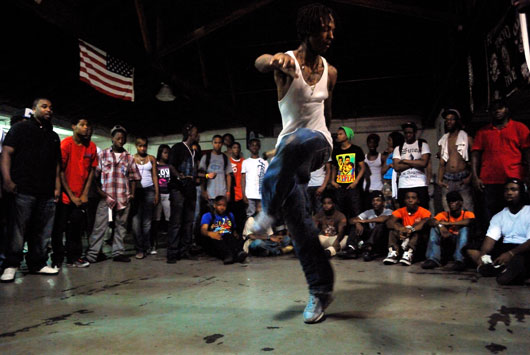

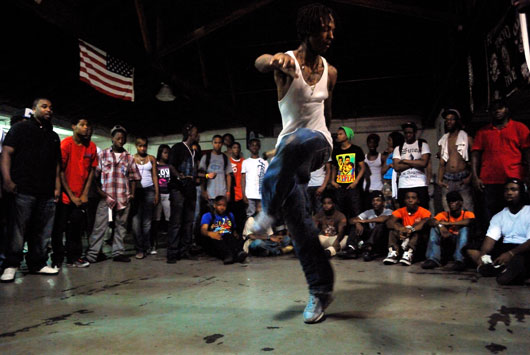

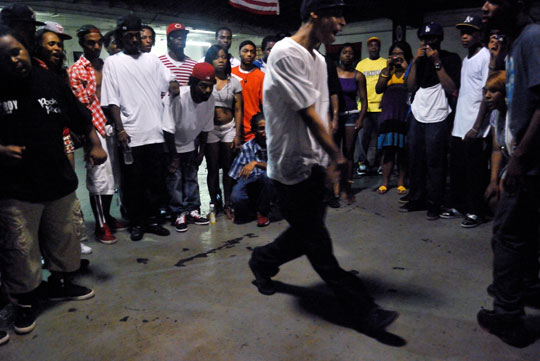

“It’s so fucking hot in here!” is the cry heard from almost everybody in the building. That includes the DJs, the spectators recording video with their iPods, the girlfriends sitting on stray chairs and buckets, and the kids with red plastic cups full of liquor—but rarely from the individuals doing the actual moving. That is, until one of them passes out from exhaustion. It’s Sunday night in the Englewood neighborhood on Chicago’s south side, and I’m fighting through a circle of spectators to get a good view of the action at an event called Da War Zone. And no better time, too, for the dancers to the left of me—The Legends Clique—look like the Voltron of footworkers. They’re comprised of the original members of the legendary Chicago dance crews Wolf Pac and Terra Squad, and the way the scales are tipped tonight, it’s not looking favorable for the opposing team.

For Chicago’s indigenous juke and footwork scene, a sweaty vacant warehouse, a school gymnasium, a rec center, a house party, or an El train platform can serve as a “place of the way,” much like a dojo. And don’t get it twisted—a martial-arts space on 57th and Claremont is where we are right now. But it could be any number of ever-changing locations on the south side. These days, two recurring gatherings take place: Da War Zone, organized by videographer and promoter Wala “Walacam” Williams, and Battle Groundz, started by dancer AG of Terra Squad and the Leaders of the New School crew. On a good night, you’ll find over 200 kids in attendance, and if not, you’ll at least catch a pretty good practice session.

Lite Bulb

Shootings, fights, and lack of usable space might prevent the scene from having a permanent shelter or center, but, still, the city’s footwork culture thrives. Here, kids leave behind street life for a different kind of quarrel—one that involves their feet rather than their hands. The energy involved is not completely unlike that of a fistfight, and someone’s bound to leave the battle feeling a bit wounded. Dancers make up their own routines on the floor, with their shuffling feet following the lower frequencies and their bodies popping to the claps. A good footwork routine, full of “soul trains,” “Pocahontases,” and “ghosts,” will have symmetry—the patterns that happen on the left side are followed through on the right—and gimmicks are frowned upon. And the music that accompanies these events is equally confrontational—like a Jamaican soundclash—pitting DJ versus DJ, dubplate versus dubplate. Tonight, DJs T-Why, Rashad, Earl, Manny, Spinn, Roc, Traxman, and RP Boo provide the soundtrack: A clattering maelstrom of toms, snares, and bass stuttering out of a portable PA, like an extremely pitched-up take on house, techno, Miami bass, and hip-hop all rolling at you at 160 bpm.

It’s debatable what supposed “wave” the juke and footwork scenes are currently in. There was a time when it was relegated to public-access TV, the Bud Billiken Parade and Picnic (an annual African-American gathering in Chicago whose aim is to promote the betterment of the city’s youth), underground battles, and high-school dances. Then there was Dude N Nem’s 2007 “Watch My Feet” video, which blew up on MTV for a sec. And now that teens from the city have begun littering the web with thousands of videos, and juke and footwork tracks are ending up in the crates of London DJs, it’s, well, headed off on another tangent. But you could safely say that the initial seeds were taking root long before most modern footworkers were even conceived.

Lite Bulb

In 1985, the House-O-Matics dance group, home to many pioneering dancers and DJs-to-be, was formed by Ronnie Sloan. They’d battle the likes of U Phi U and House Arrest 2 at local venues like The Warehouse and the Boys and Girls Club. Armando’s “Land of Confusion,” Frankie Knuckles’ “It’s a Cold World,” and later Cajmere’s massive “Percolator” were hugely popular records that influenced the era, as well as anything legendary house DJ Ron Hardy played. “I was going to The Muzic Box in ’87 at 15 years old, and I heard Ron Hardy spin and loved it,” reminisces veteran DJ and producer Traxman (a.k.a. Cornelius Ferguson). “That was the first place I heard ‘Acid Trax.’ He played it like three times. People lost their minds.”

At the same time, Dance Mania Records came on the scene, and would eventually amass a catalog of roughly 300 twelve-inches between 1985 and 2001. Heavier bass, synth- and drum-machine presets, and curse words were abundant, and simplicity played a large role in how the music was made. Most referred to the new sound as “trax,” or “beat trax,” but “ghetto house” became the more prevalent name. Jammin Gerald, Houz Mon, Parris Mitchell, DJ Deeon, DJ Funk, and DJ Slugo all cut their teeth in this era, turning the heads of many East Coast and European DJs. Eventually the word “jukin'” was coined, a phrase used to describe a banging party. “Juke” latched itself onto the later years of the Dance Mania catalog, a movement led by the likes of Gant Man, DJ Puncho, and DJ Greedy.

Deryon Webster

Juke saw some success in the late ’90s and early 2000s, even garnishing major-label singles like Beyonce’s “Check On it” and R Kelly’s “Real Talk” with remixes, but this wasn’t a push in favor of the footworkers. A style of juke with less commercial aim—and more focus on the dance crews—was being kept alive by DJ Clent (“Back Up Off Me”) and DJ PJ (“Chase Me”), both southsiders living in the area of the city known as the Low End. Their drum patterns became more distanced from house music’s origins, and the new sound began to resemble what dance crews are slugging it out to today.

“Like the saying goes, ‘We don’t dance no more. All we do is juke.’ That’s what started killing the parties,” explains westside-born Kavain Space, known to most as RP Boo. On his mantle, there’s a trophy given to him by Wala Williams bearing the words “Creator of Footwork Music,” the other, more twisted substrain of juke. In the last decade, Boo’s drum programming and sample mutilation immensely influenced underground music here, permanently changing the way footwork tracks were made. Armed with a display-model Roland R-70 drum machine and an Akai SO1 sampler, RP would create what he called “concept tracks”—jump-off points that opened the minds of many. These concepts became the first real footwork tracks, stemming from Boo’s involvement with House-O-Matics in the earliest days of the crew’s existence. “I was given an option of either ‘You’re going to dance, or you’re going to spin,’ and I was more into music so I stopped dancing,” he recalls about the time the crew’s founder, Ronnie Sloan, asked him choose his creative direction in life. Newer groups established in the ’90s, such as The Dungeon, Wolf Pac, and Gutter Thugs, needed some fresh material, and RP provided it.

In 1997, RP created “Baby Come On,” a track built from an Ol’ Dirty Bastard vocal sample that repeats itself until it becomes almost unrecognizable. Later songs like “Ice Cream,” “That’s What the Speakers Are For,” and “11-47-99” (a.k.a. “The Godzilla Track”) would continue to turn parties out, causing people to get to so excited and riled up that brawls would break out. He also once left DJ Clent so dumbfounded after dropping a remix of his own track at a party, that it caused him to have an asthma attack. The structure of a modern-day footwork track was changed from then on, with scattered triplets and pulsating bass replacing house music’s four-on-the-floor blueprint.

DJ Rashad

The early 2000s not only marked a time of change in the structure of the music, but the structure of footwork battles as well. “It was about pride back then,” says DJ Rashad (a.k.a. Rashad Harden), a former House-O-Matics and Wolf Pac crew member, and recent signee to England’s Planet Mu Records. “Everything was very organized at the time. When you’d go to a party, when you battle, everyone had their own turn. If you lost, you lost; it wasn’t just about who was the coldest,” he recounts. “Nowadays, people battle and might lose, but still think they won. There were more girls back then, too!”

Along with his colleague DJ Spinn, Rashad ran with the style that RP Boo masterminded, to this day providing footworkers with tracks that even change the dancing itself. “Most people, especially those outside the city, weren’t ready for the footwork sound when it was created—they couldn’t understand it,” says Rashad, who is now a mentor to the younger producers, many of whom have set up in the basement studio of Spinn’s Markham home in the south suburbs to work on tracks.

DJ Spinn

DJ Earl and DJ Manny are just a couple of those kids who you might find there. “I started going to Battle Groundz while I was in Creation [dance crew], and [Prince] Charles would get tracks from people like DJ Solo and Clent for us to hear,” says the 19-year-old DJ Earl (a.k.a. Earl Smith). “I was making footwork tracks at the time, but I couldn’t really get over the curve. I didn’t really know what a good track was supposed to sound like, but I had a passion for music. I asked Rashad if they were willing to recruit me, and when they did they taught me almost everything.”

It’s that cross-generational, cross-cultural pollination that is proving to be what the future holds in store for this music. Since Farley “Jackmaster” Funk’s “Love Can’t Turn Around” charted #10 on the UK charts in 1986, transatlantic conversation about electronic dance music has been flourishing. As an extension of that back-and-forth, the venerable experimental label Planet Mu recently signed three artists from the Chicago scene: DJ Roc, for his album, The Crack Capone; DJ Rashad’s Itz Not Rite EP; and one of the scene’s biggest UK exports, DJ Nate, who released his “Hatas Our Motivation” single and Da Track Genious LP on the label. Mike Paradinas (a.k.a. ?-Ziq, and owner of Planet Mu) first discovered footwork on YouTube, through a coworker. “I was really into Nate’s sound,” he says, “which seemed (and still seems) very removed from the rest of the scene. He has this very odd sense of rhythm, and his percussion seems more influenced by hip-hop/crunk than Chicago house, which I don’t hear in a lot of other footwork tracks.” Three or four years ago, Nate (a.k.a. Nathan Clark) and a few other young producers, like DJ Elmoe and DJ Yung Tellum, began uploading their tracks onto the web, exposing the more broken, twisted side of juke to the masses. On the ground in Chicago, these artists had minimal impact, existing as part of a digital underground seemingly removed from the actual physical juke and footwork scenes, but their music undoubtedly turned the heads of many overseas and on the ‘net. As a result, folks that were generally off the trail of juke’s evolution were all of a sudden name-dropping Nate, tastemaker sites like 20jazzfunkgreats and writers such as The New Yorker’s Sasha Frere-Jones began blogging about his music, and Nate’s tracks started showing up in mixes by everyone from Salem to UK funky/bass DJs.

Regardless of what strain of juke has been doing the influencing, you need only listen to Addison Groove’s dubstep-tempo footwork track “Footcrab,” Girl Unit’s “I.R.L.,” and French juke enthusiasts DJ Hilti and Kaptain Cadillac to find the connections between Chicago and the dance music coming from across the pond. With more transatlantic touring going on, there’s hope for even stronger bonds to be made. “We’ve been collecting and playing this stuff for ages!” says DJ/producer Bok Bok (a.k.a. Alex Sushon, of London’s Night Slugs crew). “It just fits into the greater whole for us. Chicago makes sense as one of the global hubs for ghetto innovation.”

It’s now 11 p.m., and Da War Zone is shutting down. What goes down inside the circle tends to stay there, and while a few salty losers may have stormed out in defeat, the community remains one of the healthiest outlets available to both young and old residents of Chicago. “I’ve been on the wrong side of the tracks before, and because of footworking, I’m a much more positive person today,” explains Lite Bulb, a passionate 20-year-old footworker and member of the Terra Squad, with seven years under his dancing belt. He just lost his friend and teammate Miah to gun violence a few weeks back, so he relies on the scene’s community for support. “They are my lifetime brothers,” he says. “I’m their baby brother, they brought me up.” It’s obvious that his, and many others’, evolution in this scene is as natural as anything else. “I love footworking, it’s second nature to me,” he continues. “I do it when I’m sleeping, I do it when I wake up. I do it when I’m at work, and at school. The money part—I don’t really care about making money from footworking. I do what I do for the love.”

The music creeps to a silent halt, everyone is shooed out the door, and people are dismantling the soundsystem. These 200 or so kids just took in a piece of footwork history 10 minutes ago, the first time the entire Legends Clique had danced together in battle—and anyone with the cajones to face ’em are now licking their wounds. It’s a massacre like I’ve never seen before, but everyone walks away with limbs intact. Outside, everyone crowds around parked cars, socializing and smoking blunts like nothing even happened.

Listen to DJ Rashad’s exclusive podcast here.