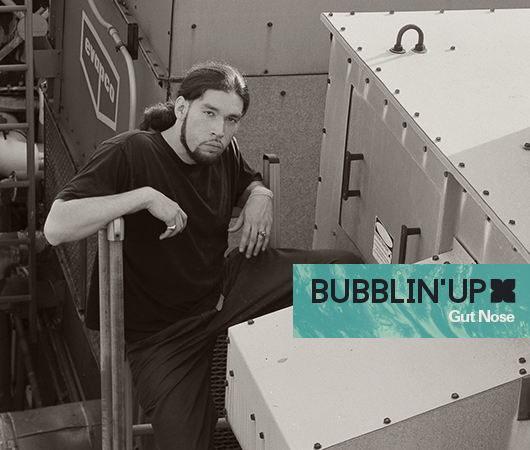

Bubblin’ Up: Gut Nose

A certain degree of bluntness can be expected from a guy with an artist name […]

Bubblin’ Up: Gut Nose

A certain degree of bluntness can be expected from a guy with an artist name […]

A certain degree of bluntness can be expected from a guy with an artist name like Gut Nose. Hailing from Queens, New York, Andrew Vagabundo makes a variation on what Actress and Moiré have called “b-boy techno,” or what Ron Morelli has called “graffiti techno,” a corroded brand of beat music that sits somewhere between hip-hop and dance music. It’s a cliché about New York, but Vagabundo’s productions do have that city saturation—tough and caked in grit, they evoke images of rats, illicit activity, piss-stained sidewalks, and violence. As XLR8R spoke to him over a slightly shoddy Skype connection, the sound from the streets was palpable—sirens, background commotion, and clips of conversations happening in the street suffused our interview. At one point, he paused mid-sentence to remark, “Hear those sounds!” None of that is especially seedy, but Vagabundo frequently manages to channel this ordinary New York noise into something crazier and more menacing.

Gut Nose (in some iteration) began on Long Island in 2000. Vagabundo’s father bought him a computer, and the sequencing program Orion Pro “appeared in front of his eyes.” He soon found the computer wasn’t “tactile” enough for him, however, and so he purchased a used MPC1000 a year or so later. (He eventually got rid of that particular computer in 2002, though he admits that a computer is “essential for doing multi-tracks, adding VSTs, and EQing.”) The MPC remains his “central hub,” even as he’s collected a table full of hardware in the meantime. The machine, so revered by hip-hop producers in particular, has clearly informed his process; Vagabundo has even worked with local MCs before, but says nothing too impressive has really panned out so far. Still, he says, “I hope I can do something in the future with a vocalist—it doesn’t have to be a rapper, it could be a choir singer or whoever. As long as the vibe is there, that’s what I’m looking for above all else.” Speaking on the Wu-Tang Clan and other East Coast hip-hop (Mobb Deep, Company Flow, and German producer Kareem’s hip-hop tracks are also suitable reference points), Vagabundo says, “The way they make their beats is they go dig in the crates for sounds, sample those sounds, and put a collage together. I always wanted to do that, so I found out how, and then just continued on. It’s like sculpting, sculpting the blade, making it sharp. You start with loops and whatever you know how to do, improve your muscle until you’re pretty strong, and then you say, ‘Oh, I want to push this bar a little bit higher.'”

Over time, Vagabundo has “strengthened” enough to bring Gut Nose into the live setting, using the same set-up he has at home. Given his increasingly frequent appearances in the live arena, he’s even been considering a move to Brooklyn to be closer to the venues he often plays. However, not everything from his studio has made it to the club. Vagabundo reveals that his tracks’ “fatness” comes from a 1980s mixer, one which is so cumbersome that he can’t bring it out into the world. This is probably why his records, including Filthy City, his new album for Styles Upon Styles, have their specific crust, and why Vagabundo is unique from the hordes of live jam dance producers operating today. It’s not that he’s using drastically different gear—just a different lens. Like many of his contemporaries, he employs an Elektron Octatrack, which allows him to efficiently blur his MPC-constructed segments together and give them “a new, completely different sound.”

Filthy City presents two sides of the same grimy coin—one hip-hop and beats-based (“Filthy City”), the other an uptempo set of jittery dance pieces that comes across like an unhinged take on the radio mix show format (“Filthnoid Mixx”). “I planned it to be like, tracks run into each other,” he explains, “like tracks either slam into each other or just evolve into each other, a natural progression into the next one, and I want to do a techno version of that.” The LP represents a very New York environment, but Vagabundo wants to eventually “get a piece of land somewhere, put a trailer on it, and make beats all day.” Yet even as he dreams of escaping, it’s impossible to deny the city’s role in his career. Out of a job after Hurricane Sandy demolished the building he was working in, Vagabundo holed himself up to record a cassette, eaT biskiT. After sending it to a few blogs, he caught the attention of the Styles Upon Styles label, with which he plans to continue working. “It’s all like a chain reaction,” he says. “They say everything in the world, even the little things, happens for a reason. If Hurricane Sandy didn’t happen, I wouldn’t have made that tape. Wouldn’t be talking to you right now.”