Bubblin’ Up: Nils Frahm

Nils Frahm was in the studio one day, recording a new track on the piano, […]

Bubblin’ Up: Nils Frahm

Nils Frahm was in the studio one day, recording a new track on the piano, […]

Nils Frahm was in the studio one day, recording a new track on the piano, when he was suddenly forced to take his hands off the keys. A cell phone started ringing and the 30-year-old German multi-instrumentalist was temporarily stunned. Most producers would erupt in anger at such an interruption; Frahm just laughed, before calmly moving onto the next note. Tape was rolling the entire time, and the whole episode—stray ringtone, laugher, and all—is now a permanent fixture of the piece. “I’m very grateful for that moment because it’s fun and it shaped my improvisation,” he says, fondly recalling the incident.

Frahm is an unusual breed of engineer—he takes pleasure in using the ‘wrong’ recording equipment and enjoys capturing the ambient sounds most would strive to eradicate. “I don’t really want to design something perfect, something artificial,” he explains. “I just want to catch a good moment. When they occur—when something’s wrong, something’s clicking or cracking—I always feel like it adds something special.”

His own breath lingers throughout 2011’s Felt, his delicate, critically acclaimed studio debut for innovative London imprint Erased Tapes. Recorded in the dead of night in his Berlin studio, Frahm was concerned about disturbing his neighbors with his playing. Ever polite and respectful, he dampened the sound of his piano by stuffing it with thick pieces of felt and placed microphones as close as possible to the strings. The resulting recording was incredibly intimate—one can hear every sigh, every creak in the floorboards. Listening is almost akin to sitting right there with him, sharing his piano bench and his quietest moments.

Of course, he says, not all accidental noises are worth retaining, “but it’s good to have open ears for what’s interesting or compelling. It’s about selecting the right accidents.” It’s this philosophy that allowed the classically trained impresario to seamlessly transition into the world of electronic music—in recent years, he’s made appearances at major festivals like MUTEK, Primavera Sound, and Decibel, all of which left audiences buzzing.

Though he is the only professional musician in his family, Frahm grew up in a musical household. His father, a photographer who worked with ECM in the ’70s, played a bit of piano and guitar, and kept classical and jazz records—including a treasure trove of promotional items from the label—around the house. “The music playing at home was extraordinary,” Frahm remembers. “He was really open-minded, musically,” and encouraged his young son to experiment with a range of instruments, from the harmonica to the drums.

Eventually, Frahm settled on the piano. It was largely out of convenience; his mother already owned one, though she didn’t play much herself. As soon as his fingers pressed down on the ivory keys, he felt a connection to the instrument. “The piano is easy to start with. It’s like learning English; you can learn how to say a few things very quickly, just by pressing some keys.”

As a child, Frahm studied under Nahum Brodski, who was himself a student of Tchaikovsky’s last protégé. Determined to mold the eight-year-old Frahm into a world-class classical pianist, Brodski worked him hard—almost too hard, sometimes. “I kind of loved and hated him,” Frahm says. “He smelled like garlic every time he came over. And sometimes he forgot his teeth. I was a little scared of him. But as crazy and eccentric as he was, he was also really wonderful and had a big heart.” Brodski often gave Frahm extra lessons without charge, at one point working with him on a near-daily basis—that’s how much he believed in Frahm’s potential as a classical concert pianist.

But after six or seven years hacking away at Chopin, he’d had enough. “I went through some hardship in that time,” Frahm remembers. “Instead of playing football outside with my friends, I was inside practicing two bars of a complicated piece 400 times. I kind of hated it, but in the end, it made me tougher, and it made me realize that nothing comes from nothing. You have to suffer a little bit to achieve something, and you have to stick with something to be good at it.”

Frahm continued on with the piano—but started to move beyond his classical-only repertoire. He joined bands, but that didn’t last long; he loathed coordinating gigs and recording sessions with a group of people who didn’t share his work ethic, and at 16, he decided that it just wasn’t worth the effort. It was around that time that he was introduced to the computer, and learned how to record on his own. All the while, his appreciation for legends like Steve Reich and Philip Glass continued to grow and inform his technique. “It was really fashionable at that time to make interesting click-and-clap beats out of field recordings,” he says. “For most people, it seems odd, because they put me on the classical shelf, but I played in rock bands and all kinds of noisy, experimental groups. A lot of that music wasn’t released, but I spent all this time developing these skills as an electronic-music producer that never really went away.”

Eventually, he circled back to the piano, recording his first solo effort in 2007. The 30-minute improvisational piece was recorded as a Christmas present to his friends and family, but the album soon found its way to the Sonic Pieces label. Recognizing Frahm’s substantial talent and the album’s beauty, the imprint released an edition of 333 copies in 2009, which promptly sold out. “I kind of wanted to stop them from doing that, but they talked me into it,” he says. “It was a surprising experience. Way better than my expectations—it was a tremendous success.” A second edition of 500 copies was pressed to meet demand.

He soon followed with The Bells, collaboration with close friend and future labelmate Peter Broderick, for Swedish label Kning Disk. The album was recorded in a two-day session inside of a massive, reverberant church, which was chosen for its treatment of a string-quartet performance he’d witnessed . “[Peter] is really in the same kind of spirit as I am. He likes unusual ideas. He told me, ‘Play a song you can imagine me rapping over.’ ‘Play me song with only three notes.’ ‘Play something with me laying on top of the piano—a song called “Peter’s Lying Dead in the Piano.”‘ So I improvised and then I edited the best pieces together.”

Because of his connection to Broderick, Frahm’s first two albums were picked up by Erased Tapes; the label re-released them and signed Frahm for three more records. Aside from 2011’s Felt, he’s released Juno, a two-track solo synthesizer EP, Screws, a nine-track collection of songs recorded with nine fingers that was named for the tiny metal objects implanted in his hand after a traumatic thumb injury, and Juno Reworked, a re-release of the long-sold out Juno with remixes from Border Community’s Luke Abbott and Warp’s Clark. Anne Müller, Ólafur Arnalds, and F.S. Blumm have become collaborators, and his Juno pieces have surfaced in Four Tet’s DJ mixes.

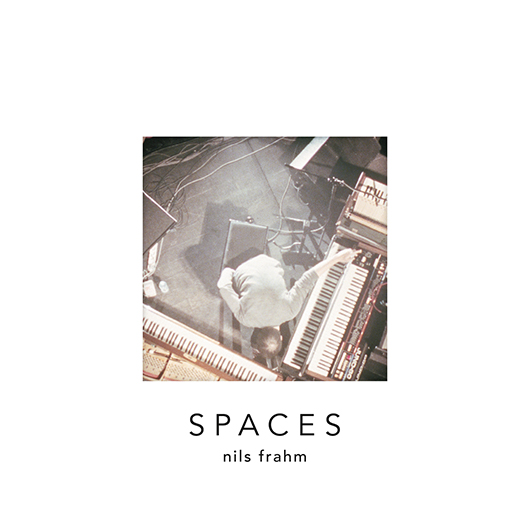

Frahm is now about to release Spaces, an album that aims to capture his unique live show, which blends piano improvisations with synth experimentations. His unconventional approach to the piano—once the subject of much snark in online forums for his strange recording style—has shined a new light on the modern classical genre and earned Frahm accolades from around the world. “All these preconceptions about recording and making music, hearing music, and all these dogmas from people about how you have to do things this way or that way—I always thought that was wrong,” he says. “I hate dogmas. I hate principles. When people have the answer before the question, it’s always sketchy.”

“I just try to explore wrong ways of making music in order to create something interesting.”