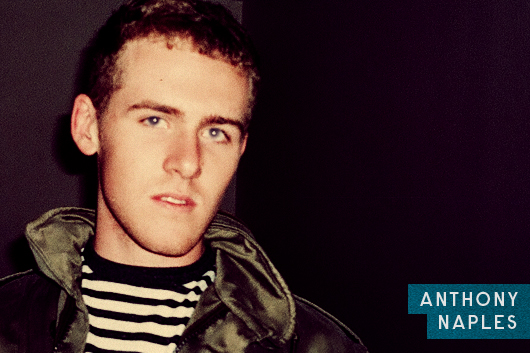

Bubblin’ Up Week 2013: Delroy Edwards, Anthony Naples, Roche, and Huerco S. Take on House in Their Own Way

On his 2009 album Midtown 120 Blues, DJ Sprinkles declares that, “House is not universal. […]

Bubblin’ Up Week 2013: Delroy Edwards, Anthony Naples, Roche, and Huerco S. Take on House in Their Own Way

On his 2009 album Midtown 120 Blues, DJ Sprinkles declares that, “House is not universal. […]

On his 2009 album Midtown 120 Blues, DJ Sprinkles declares that, “House is not universal. House is hyper-specific,” suggesting that the genre’s utopian birth story is anything but. In truth, house’s early years were often the product of disparate, fiercely independent personalities and spaces, which is why today’s landscape can feel suffocatingly homogenous, particularly if one doesn’t know where to look. Beneath the deep-house facsimiles and Ibiza-fication, though, there is a rising generation of producers taking inspiration from the genre’s freeform legacy. That being said, despite attempts to lump the following four producers (and their like-minded contemporaries) under the nebulous banner of “outsider house,” their music doesn’t necessarily sound alike, and they couldn’t truly be categorized as operating within any sort of concrete ‘scene.’ Still, they are united by one thing in particular: a shared desire to embrace house as a medium for their individuality.

Photo by Erez Avissar

Like many of his contemporaries, 21-year-old Brian Leeds seems pretty nonplussed about the production process. Before moving to Kansas City, MO, a year and a half ago, he was honing his craft on FL Studio (which he still uses) on his mother’s computer in Eastern Kansas, where he grew up. Now working with a hodgepodge of equipment—Casio keyboards, tapes, and a mixer—Leeds creates dissociative arrangements as Huerco S. His tracks recall house via occasional signposts only: an old-school rhythm here, a resonant square bassline there. They are grit-saturated and loose from the grid, and he’s quick to agree that an assortment of similar US and European experimenters have had an influence on his music. “Wania, Börft, all the General Elektro stuff, Meakusma, Marcellis on Workshop, Dean Blunt…,” he rifles off, before acknowledging classic tracks from New York, New Jersey, Detroit, and Chicago in addition. While he may be able to find kin in these sounds, Leeds’s music is particularly unique in its almost psychedelic approach to composition. “It’s like digging into the Earth and finding a bone and dusting it off. It’s still ancient and raw,” he says. “Even if I had tons of gear, I think it would still sound [the way it does]. Precision isn’t the endgame.”

As his profile has risen in the last year, he’s been offered some remix work, most recently of Jay Weed’s “Tunnel.” Given that the song’s ultra-precise bass music is perhaps the polar opposite of his usual style, it’s not surprising that Leeds describes his rework as a “deconstruction.” He claims he usually tries to, “contort and hint at the original track, [and] view it through a kaleidoscope,” but on “Tunnel” he tried to eschew the bass of the original and “focus on the higher textures.” This willingness to forgo popular structures carries over to his latest work, a nearly beatless album which is still in production. He has an array of other music in the pipeline as well: a 12″ for Future Times, a reissue of his Opal Tapes record from last year via online retailer Boomkat, and a record as Royal Crown of Sweden, set for release on Anthony Naples’ as-yet-unnamed label. As it turns out, Leeds and Naples are also touring North America together in the next couple of weeks.

Raised in Florida but now a New Yorker, Anthony Naples has lately had the unenviable task of following up a hit debut single, last year’s “Mad Disrespect.” Recent trickles of new material—he remixed Brooklyn trio Lemonade and released an uncharacteristically brutal track via Opal Tapes last month (which he describes as a one-off)—are set to turn into a deluge in the next month or so. Between a proper follow-up 12″ on Mister Saturday Night

(the label and party behind “Mad Disrespect”), a self-released white label, an EP for Trilogy Tapes, and a remix for Paul Woolford‘s Special Request project, Naples is countering sophomore expectations with a variety of experiments.

While “Moscato,” the forthcoming Mister Saturday Night record, was conceived around the time of its predecessor and thus has a similar sound, the other releases are the product of recent forays into hardware, a change that the producer hopes to further incorporate. Originally computer based, Naples describes his new set-up as involving more “pushing [of] buttons.” “In the last few months I’ve gotten a drum machine and samplers,” he says, and this has made for a more “rugged” sound. “I want to [compose] really spontaneously and just record,” he continues. “A lot of the stuff I’ve done in the past I’ve had to think about so much because of the workflow issue, and now that I’m realizing you can do things [as] a mixture of both [hardware and software], there’s no reason to go back to any other way.”

This newly instinctual approach seems ideal for an artist who has never put much stock in the concept of polish. “I’ve never EQ’d a single thing,” he claims. “I don’t think it really matters.” Naples’ debut may have graced its fair share of year-end lists, but he is uninterested in trying to replicate its success, as setting out to produce a “chartable” single is at odds with his methods. He describes his tracks as “genre studies,” the results of “getting really attached to one idea for a month.” “I’m not trying to do anything in particular,” he says. “I’d just like to refine what I’m doing based on what I have.”

This modest approach may be in part due to his relationship to New York, where he feels he is “not part of any group.” “I’m friends with Nick [Dawson (a.k.a. Bookworms)], Matt Gardner, who records as Terekke, Justin [Carter] and Eamon [Harkin] (of Mister Saturday Night)—I go to their parties a lot,” he explains. “But I don’t have a lot of friends that make music, so there’s never talk of music. A lot of the time, I’m less inspired because I have no one around me who talks or cares about it. My roommate has to put up with me blabbering about the new Levon Vincent record. My girlfriend doesn’t want to hear about it either.” Even so, Naples praises the L.I.E.S. imprint for “reinvigorating the city,” and the rawness of his new material certainly hints at the label’s influence.

On the whole, Naples will continue to only produce when the mood strikes him, but lately he has been hard at work getting his DJ skills up to par, both for the upcoming North American tour with Huerco S. and for a string of European dates that includes stops at such prestigious venues as Berlin’s Panorama Bar.

Photo by Sam Jackson

San Francisco’s Ben Winans started Roche as a hip-hop project around 10 years ago, initially releasing through his own, now-defunct Solos Records. Over the past decade, Winans has shifted away from hip-hop toward an earthy, psychedelic house sound, a change that really culminated on 2010’s Degage EP, which he describes as a “turning point,” the result of digging deeper into dance music in prior years.

“[One of] the initial [producers] that got me into dance music was Theo Parrish,” Winans says. “He has tracks that are just straight-up hip-hop tracks. Through that, I was able to give [dance music] more of an open-minded listen. I could hear the elements of hip-hop in his dance productions and it stopped being about whether it’s a dance song or hip-hop song—’those are good drums, nice chops, nice bassline.'” He mentions Daft Punk in a similar light: “a track like ‘Da Funk’ is almost more of a hip-hop song.”

While absorbing these productions, Winans was also having formative club experiences at San Francisco’s Gentlemen’s Techno party, thrown by C.L.A.W.S. “I only went once or twice, but it changed my mind on the whole scene aspect of dance music,” he says, as it represented a “dark room” alternative to the garishness of rave culture. Still, Winans is not particularly drawn to making “club friendly” music: “I am into the further leanings of house and techno. I don’t want to have the dancefloor as a premeditated thought. I might every once in awhile; maybe if everyone thinks I’m a weirdo I have to try to make something normal. But that stuff usually ends up being the weirdest.”

Although actual clubs are generally far from Winans’ mind, the loose, on-the-fly aspect inherent to DJing is frequently present in his productions. Two of the tracks on his recent Mathematics EP, Auragan, were more or less finished in one take (he’s currently putting together a longer EP for the label, with a spring release date). On the other hand, his 100% Silk EP, A Night At The Haç, featured a more involved process of editing. In his words, he was trying to, “cater to the vibe of the label while still doing [his] own thing.” Winans hasn’t always produced in such an open way, though. “When I was doing the hip-hop stuff it was like, ‘I’m doing this, fuck you, I don’t care what you think,” he remembers. “Now, I’m more open to constructive criticism.”

Winans also hones his tracks playing live. “Most shows are local SF shows, which gives me the opportunity to bring out a ton of gear. [In that setting,] I can mess with any aspect of a track,” he says. Faraway shows in Hong Kong and New York have limited the amount of gear he was able to bring, but Winans saw them as a different sort of opportunity, explaining, “with limitations you go in different directions.” He hopes to test these limitations on a European tour later in the year with his 100% Silk labelmates Bobby Browser and JM II in tow.

A listen through 22-year-old Delroy Edwards‘ SoundCloud reveals a producer who’s at least as interested in footwork as he is in house, though it’s the latter that’s pushed him into a kind of spotlight. Thus far, all of his releases have appeared courtesy of Ron Morelli’s L.I.E.S., an imprint dedicated to a variety of raw and reckless electronics. Edwards, now based in Los Angeles, met Morelli when the two worked at A1 Records in New York together. It was Morelli, he explains, who convinced him to move away from footwork.

“Ron was playing me the first few L.I.E.S. releases, and it was sort of similar to the stuff I was making—abstract, sample-based, beat-driven footwork, at the time. And I just thought I could try my game at making house tracks.” “4 Club Use Only,” Edwards’s first 12″, was a direct result of Morelli’s encouragement. “Ron was like, ‘you should make me a record,'” he remembers. “I was into house more as a DJ—I hadn’t really tried producing it.” DJing is still a priority for him, and he will be touring Europe with Morelli in the spring.

If L.I.E.S. is known for a back-to-basics approach, Edwards fits right in. He explains his set-up as quite minimal: “I really don’t have much. My set-up is super simple, it’s just shitty stuff that I come across—simple keyboards and drum machines—and I record to cassette most of the time.” Moreover, he does little in the way of editing, and says that most of his tracks are simply live jams (he doesn’t, however, plan to play live shows).

“I’m just more into the rhythms, and just rough tracks,” he says. “House music these days is so convoluted. And I feel like the simpler the better. Use what you have and make the best of it.”

After years of precision-tooled dance records, this stripped-down approach inevitably prompts ideas about a “new trend.” But as Edwards points out, this spirit has been in dance music since the beginning. “House has always been outsider, you know,” Edwards says. “It’s just coming back. Once people are adjusted to the sound, producers are able to go off and get deep with it.”