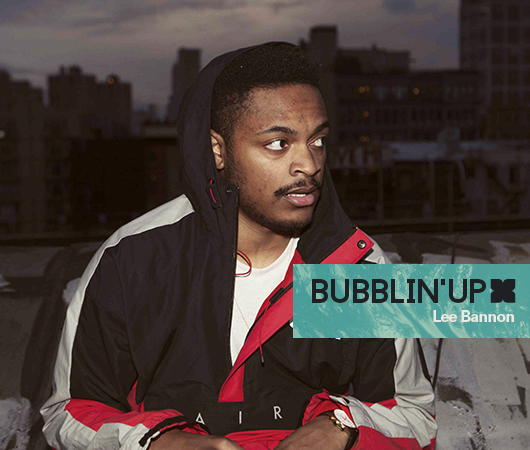

Bubblin’ Up Week 2014: Lee Bannon

“I’m not really into much hip-hop right now,” says Lee Bannon with a shrug. It’s […]

Bubblin’ Up Week 2014: Lee Bannon

“I’m not really into much hip-hop right now,” says Lee Bannon with a shrug. It’s […]

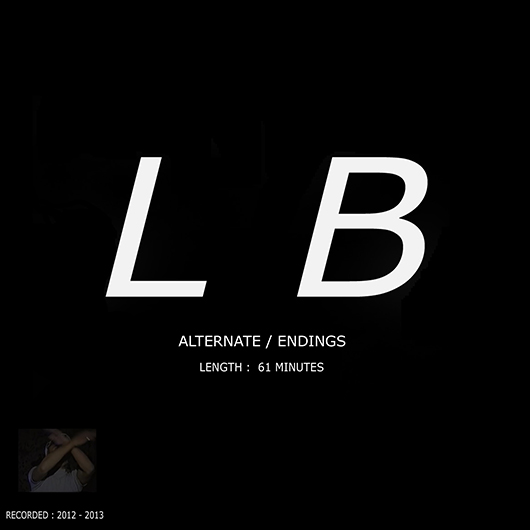

“I’m not really into much hip-hop right now,” says Lee Bannon with a shrug. It’s a surprising statement coming from a guy best known as the producer and touring DJ for rap wunderkind Joey Bada$$, but one listen to his upcoming Alternate/Endings LP for Ninja Tune makes it clear that he’s telling the truth. Instead of jazzy, Dilla-flavored beats or blissed-out trap, Bannon’s latest effort is full of sinister synth stabs, ambient found-sounds, and aggressive jungle breakbeats. Granted, for those who have been closely following Bannon’s work outside of the rap world, Alternate/Endings just seems like the logical next step. Since beginning his musical career as a teenager, Bannon has slowly morphed into an experimental producer whose wide-ranging interests stretch further than those of the average beatmaker. Bannon’s new record is both the culmination of that evolution and the first step in an ambitious, years-long plan to establish himself as a true artist on his own terms.

Though he now lives in Brooklyn, Bannon started producing music at the age of 13 in his hometown of Sacramento, California. “My friend Anthony moved from Chicago and introduced me to beat machines and MPCs,” says Bannon, who immediately became infatuated with electronically produced music of all types. “That summer, I read all kinds of articles. I found what random people—someone like Venetian Snares—would use for software. It was right when Cakewalk released a program called Project5. I downloaded it and started with that. Eventually, I got a Korg Electribe, kept gaining gear, and the process continued throughout junior high school and high school.”

Bannon’s early beats were composed with the hope that someone might want to rap over them, and he’d use samples and presets with specific MCs in mind—often Bay Area locals. “The first person I worked with was The Jacka, who introduced me to a bunch of other people. Back then, I’d make six beats over a two-week time period and put it out. I started seeing little beat tapes going around [the internet] when I was in high school.” Bannon’s strategy paid off, and within a year of his first collab with The Jacka, he had gained recognition from blogs like 2Dopeboyz and OK Player. Though he was primarily known in the hip-hop world at that point, Bannon had always been interested in other sounds. He soon fell in with the small-but-fertile Sacramento music scene, which Bannon suggests would make for a great music documentary. “There were places like The Townhouse and the Press Club. I’d run into Zach Hill and Stefan Burnett [of Death Grips], Chelsea Wolfe, Ganglians. We all went to each other’s shows. Everyone who has emerged from that scene is starting to make really incredible music,” says Bannon, who fondly remembers rolling weed with Hill and running into Lee Spielman from Trash Talk at the clothing brand Lurk Hard’s warehouse. (There’s a mixtape built entirely from Marvin Gaye samples from this period titled, fittingly, Me & Marvin that’s still worth checking out.)

Around the same time, though, Bannon was about to get a big break through his then-manager Jonny Shipes, who also worked with Big K.R.I.T. and founded weed-rap collective Smokers Club. “He’s like, ‘I have this kid, I’m thinking about taking him on,'” says Bannon, who immediately liked what heard from the teenaged Joey Bada$$. “I started sending him music and he started getting bigger. He was making a name for himself and the tracks that I did just happened to snowball with that,” says Bannon. He started coming out to New York all the time and after his first tour with Joey Bada$$, Bannon decided not to return to Sacramento at all. “I had done Jimmy Fallon [with The Roots], there was just no reason to go back. It was Sacramento times fifty—just walk down the street and meet people like Daniel [Lopatin] from Oneohtrix Point Never. I got inspired.”

After touring with Joey Bada$$, though, Bannon soon began itching to produce music on his own terms—even as his profile as a hip-hop producer continued to rise. “There’s a big gap between now and then. Ever since right before I started working on Alternate/Endings, I was making beats for other people. In February, I decided to stop everything and not be just Joey’s producer or beatmaker—to totally abandon all that and just be an artist. This is the first time I’ve ever felt like I was making music for myself. Not giving a fuck. Making whatever I want,” says Bannon. Though it’s true his music has changed dramatically over the past year, Bannon did in fact release quite a lot of his own music both before, and during, his time with Joey. The spaced-out Fantastic Plastic, Caligula Theme Music, and its sort-of sequel Caligula Theme Music 2.7.5 are all excellent instrumental releases, which garnered comparisons to the codeine crawl of Clams Casino and further broadened his audience. (“I’m probably the only producer you’d ever seen on both OK Player and Gorilla Vs. Bear,” laughs Bannon.)

Though he doesn’t mind revisiting his mixtapes (“Those was before I figured out I only wanted to do music that I genuinely like,” he says. “It was just stuff I had on my computer that I put on a ZIP file and put out.”), Bannon separates them thematically from his current output and views Alternate/Endings as his true debut LP. “I really wanted Alternate/Endings to come out the right way, so it could be taken seriously as a body of work,” he says. He tested the waters by dropping “NW/WB” online without any press release or fanfare. The track soon got him attention from labels as wide-ranging as R&S, Warp, Tri Angle, and even the usually goth-oriented Sacred Bones, but he ultimately settled on Ninja Tune. “I took two weekends to map out my five-year plan. What I want, and what I need, and how I want to execute my goals. I got a good lawyer, good PR, good managers—it was a great learning experience working with Joey because I saw all the moving parts,” he says. He also released the Place/Crusher EP last October, which—though mostly lacking the high-bpm breakbeats of Alternate/Endings—Bannon sees as part of his more mature work. “I wanted to make something that was aggressive and wasn’t so popular,” he says. “Everyone was doing trap or house. I just didn’t want to get stuck in that world. I don’t have a problem with those things, I just don’t want to be that guy. Instead of being behind the curve, I’d rather be ahead of it.”

Bannon takes care to compare his own music only to people he sees as serious, big-name artists and doesn’t particularly like it when critics compare his work to contemporaries like Rustie or Clams Casino. (One exception is fellow Ninja Tune artist Actress, who he compares to Michael Jordan; of course, this scenario leaves Bannon as the metaphorical Scottie Pippen.) Instead, his preferred references can mostly be traced to the late ’90s—producers he heard in his teenage years or that have had time-tested cultural impacts. “I always use these examples of Fatboy Slim, Moby, or even Aphex Twin. Everybody talks about Dilla and [other beatmakers]—and I loved them growing up—but [Fatboy Slim and Aphex Twin] executed some of the greatest instrumental tapes of all time. They were so great that people don’t call them instrumentals. It was just music. You couldn’t put it in a bottle and call it a beat,” he says. Two of his favorite records of last year were by Boards of Canada and Tim Hecker—artists that he views as part of this category as well. Acutely aware of how albums are made and perceived by critics over time, Bannon was rather meticulous when putting together Alternate/Endings. “Everything about the album is thought out. I didn’t want anything to put it in 2014. If you see this in a bin and didn’t know it came out this year, and it was kind of dusty, you might think it could have come out in ’95. That’s how I was thinking about the music.”

Alternate/Endings will be released later this month, but Bannon is already deep into his next two projects—another upcoming EP and full-length—and throughout our interview he plays us in-progress tracks, some of which bare traces of trip-hop; it’s moody music, more reminiscent of Burial than drum & bass. Still, he also doesn’t discount the idea of working with rappers again (he mentions Death Grips, Mykki Blanco, and Le1f among a handful of MCs that he admires), though he doesn’t seem particularly excited about making traditional beats. In the live setting, his music has gravitated toward the dance-oriented sounds found in his new work, giving the performances an electric new energy. “With the hip-hop stuff, people are just stuck in place, nodding their head,” he says. “But if I’m playing a really crazy break at 171 bpm, people are going crazy. They’re not looking at me perform, they’re just moving.”