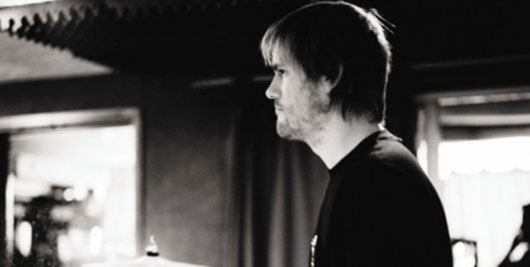

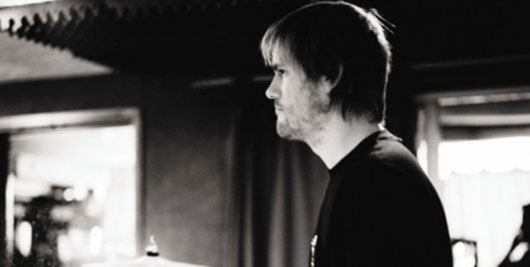

Building an Iconic Sound: Portishead’s Geoff Barrow

As one-third of Portishead, Bristol-based producer Geoff Barrow has used the mixing board as an […]

Building an Iconic Sound: Portishead’s Geoff Barrow

As one-third of Portishead, Bristol-based producer Geoff Barrow has used the mixing board as an […]

As one-third of Portishead, Bristol-based producer Geoff Barrow has used the mixing board as an instrument to arrange haunted electronics, percussive cast-off, and furrowed laments. He’s also produced “traditional” records for bands such as The Coral and The Horrors, helping to hone rough ideas in the studio with instructions of “half of a little bit, or a whole lot of it,” as he describes his informal way of applying EQ, compression, and other things. However, with his recent turn as drummer of BEAK>, a Krautrock-infused trio, and as a musician and producer for no-wave politico Anika (who has a dubby album on Stones Throw), Barrow has adopted a live tracking, overdubs-free approach to raw, crawling groove he finds especially fulfilling. Eschewing the idea that recording should indulge every snare smack and leave creative balance for the mix, Barrow took a moment to discuss discordant beauty and his projects’ philosophy that “it’s better to use fewer channels and make more decisions.”

XLR8R: The BEAK> and Anika records are said to have been recorded within two weeks. For comparison, how long did the recording of Portishead’s Third take?

Geoff Barrow: It’s kind of weird, as a lot has been made of the timeframe of [BEAK> and Anika], where I really think it’s more about the ethos. Compared to Third, I don’t think they’re an awful lot different, in a sense that if something works it works and if it doesn’t it doesn’t; [on] Third it just took longer to make things work… for me anyway. An Anika or BEAK> track immediately sounds good when everyone is in the studio playing it, and everyone is happy [with] what it represents, while a Portishead track like “Magic Doors” [from Third] was written in 2003/2004, and I wasn’t happy with it until much later. It does my head in, though, the constant fiddling. The idea you could go in, put the mics up and it be about material and vibes rather than using production to make ideas work, rather than running a beat through a tape machine for sibilance—that’s where I’m at [now]. It’s a whole computer generation, fucking about on this endless quest of seeing what a guitar could sound like if it were simulated as playing through a car stereo with speakers made of tin pans. And if someone wants that, fine for them, but even though it’s these infinite possibilities, it feels so restrictive. For BEAK> and Anika, just having three musicians and a singer in a room is a pleasure. A band like Can would just gather, record, and they would sound so balanced and at the same time capture all these dynamics. I’ve become fascinated with this, because I think it’s been lost among all the mastering and optimizing plug-ins.

Portishead “Magic Doors”

BEAK> and Anika have a prominent amount of reverb and panning, however, so a certain amount of coloration had to have been preconceived. Did you plot out any processing concepts?

I think sometimes musicians hide bits of average writing through production, and the availability of aural exciter plug-ins has made masking and manipulating a stock thing, which is quite boring. Whereas people like Joe Meek [a British engineer/producer of the ’50s/’60s known for creative mic’ing, distorting, and comping] were just fucking mad. The reggae guys, they had a driving force of trying to create otherworldly, spiritual music. So there’s still an element of that, which you can find in the reverbs, which do more to expose rawness than hide it. What I really love to hear is a really amazingly written song that’s off-kilter, and that doesn’t hide its wrongness … bands like the Plastic People of the Universe, or the [Jimi] Hendrix stuff recorded with Curtis Knight—it’s just rough, and captures what happened there. There were elements of doing a mix, but not to correct anything. I’d rather capture a mistake than work in a constantly unfinished state.

So, the tonal bleeds that can be heard in the quieter moments on some BEAK> tracks are intentional “mistakes”?

Everything is bleeding on everything, but it’s not the point—it’s just what is part of it. There’s no isolation; you couldn’t strip the guitars, it’s all over. The Anika dubs sound the way they do because you can’t get rid of the vocal, as it’s being performed in the room with the band coming from an amp, and it’s quite exciting. BEAK> is three vocals going through a mixing desk into a little Roland Space Echo into an amp, and the amp is mic’ed up, so it’s all happening in the room with the instruments. It’s actually a lot less considered than it seems like it’s being perceived, though. The instruments are being set up. I don’t care what mics are on anything as long as they’re on something. I don’t care about maximum level. If the instruments sound good, it will sound alright. Really, I’m impatient as well—I want to put something through. I’m not bothered if something goes into another piece of gear and loses dB and volume, or you shouldn’t use this stereo plug when a mono will do. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think BEAK> and Anika are the greatest records I’ve ever recorded and you have to dig it. It’s just a lovely feeling to capture what’s happening on a creative, musical level, not to turn oneself inside out on a production level.

Anika “Yang Yang”

Anika’s Anika (Stones Throw) and BEAK>’s BEAK> (Ipecac) are out now.

For more of Building an Iconic Sound read our features with Squarepusher, Mala, and Moby.