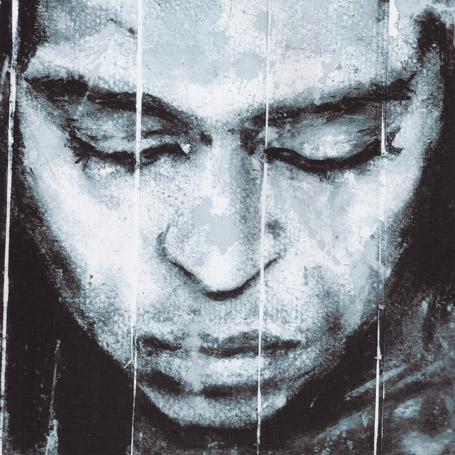

Deantoni Parks: “For me, rhythm is the study of time.”

On his solo debut, 'Technoself,' the gifted drummer bridges the analog-digital divide.

Deantoni Parks: “For me, rhythm is the study of time.”

On his solo debut, 'Technoself,' the gifted drummer bridges the analog-digital divide.

Whereas many producers are using software to mimic the sounds of live instruments, Deantoni Parks is using live instrumentation to mimic the sounds of something that was created on a computer. With a half-analog/half-MIDI drum-and-keyboard setup, Parks creates compositions that fuses his futuristic sensibility with the improvisation of his jazz background (he serves as a part-time faculty member at the Berklee College of Music and the Stanford Jazz Workshop). Although he’s mostly played in groups—including BOOTS, Bosnian Rainbows, Flying Lotus, John Cale, the Mars Volta, and Sade—his new album Technoself, out now on Leaving/Stone’s Throw Records, marks Park’s first solo effort. The album’s opening and closing tracks were recorded at live sessions, emphasizing the fact that the entire album uses no overdubs, and is played 100 percent live.

How did your current setup come to be?

It initially came from seeing Kenwood Dennard use the half-MIDI, half-live setup. I’ve been playing drums for so long, and they’re great and dynamic, but those sampled sounds and production methods inspired me so much, and I just wanted to integrate the keyboard to give me a palette. I’m familiar with piano, and the MIDI-controller side, and they’re great percussive instruments, so to have the “war drum” live kit still there—the hi-hat, the snare, the bass drum—accompany those samples was exactly what I was looking for.

Can you talk about the process of how you go about your live shows versus recording in the studio?

It’s the same process. Going into it, I don’t know exactly what I’m going to play. I sit down with some palettes and all the elements I want, with a vague idea of the rhythmic structure and tempo and loose base style.

Did the Technoself idea grow out of the live setup?

Yes, Technoself is directly an effect of the live setup; they’re kind of synonymous. I refer to the setup as a method, because it just crosses so many walls that I needed to be crossed. The live setup directly affects the way the record sounds because everything is recorded live with no overdubs. So the final product, what you’re hearing on the record, is just what it sounded like live.

How are you managing to get all the sounds that you want out of such a bare-bones kit?

Adding the MIDI controller really helped solve that problem. I had to drop a stick and that was the hardest part, but you gain so many opportunities with the samples. I feel like this is something I couldn’t have done ten years ago. I think the timing of it is perfect, because I had no where else to go, not that I’ll never work with bands again, I’m just over the concept. Especially when it comes to composition and arrangement, it’s too much compromising. When you’re in that moment, in your own ensemble, you’re arranging it by the moment. Everything is tight, it’s together, it’s amazing. That’s how I like writing—you get thing done more quickly, the software is made so that things get done quicker. For me, this is my way of climbing that technological tree and speeding ahead to make things happen quicker and get better results.

What is it that the live setup has allowed you to accomplish that you couldn’t with more traditional production methods?

The live setup is me mimicking the engineer—mimicking the ability to cut-and-paste in weird places. So that’s a great thing that I can mimic on the spot. The sample part is more mimicking the sequencer or getting that loop going, and that’s what I’m imitating. I’ll bring in those elements, and then I’ll add the layer of tonality to find where these sounds clash with actual notes, and then build a composition from there.

It sounds like you are trying to get to the point where your drumming sounds like something that could have only been programmed by a computer.

There’s so much improvisation, that I wanted pieces that sounded like they were something done in post-production, and it comes that way because of the tightness of the sampling. It’s sort of the illusion of making it tight to the point of it could have been programmed. Obviously the drums I’ll make sound like amazing live drums. But some of the best programmers have always sampled those kinds of drums—the real drums—and make them sound amazingly tight and structured.

I want the feeling of having a drink before a set…very loose, just hanging out. But then you sit down to perform, and it’s like those old jazz musicians—that’s how I want to feel. I’m just gonna create right now, and they’re gonna love whatever I create on the spot.

Have you always had an interest in the combination of live drums and sampled sounds?

I always programmed music when I was very young, I always had that interest. When I started making the first sequences, older family members who knew the early electronic records would say, “That sounds like a Cybotron song!” or “That sounds like Kraftwerk!” And I was like, “Who are these people?” So I’ve always been on my own slow incline as far as composition, writing, performing regiment.

That sampling of human voices on the record, in a way, implies all of us in the Technoself idea.

As far as sampling a sound, the voice is probably the best sound to sample. The orchestra is in your voice. Bass percussion, and highs—even when you’re breathing, those sounds are just so cool Under magnification and made loud, those sounds are incredible, even if it’s just someone hiccuping. I wanted to have that represented on this record.

There are points in the music where the digital and analog are getting along well, and other points where they feel like they’re fighting to be heard.

Yes, absolutely. I love pure electronic records that have no acoustic sounds on them, but when you take those sounds of those records, and you layer them with a live kit—a war kit, big bass drum, big marching snare, forceful drums—it becomes something futuristic, and something that’s 100 years old. They do fight, but when they get along…that’s kind of what I’m living for right now.

“I think that’s why people like music so much—it makes them feel like they have a little bit of control of time.”

Can you talk about your own philosophy of rhythm?

For me, rhythm is the study of time. I look at myself as a person who studies time. It’s a horology type of thing. Time is such a strange concept that nobody understands, so its sort of like trying to create a structure of time, or mimicking something with a set pattern. It’s carving out these time pieces. I think that’s why people like music so much—it makes them feel like they have a little bit of control of time, which none of us do. It’s like knitting or something.

It’s interesting how the study of time comes out on a record that combines the hundred-year-old war-drum sounds with such a futuristic concept.

Ideas don’t happen as quickly as I would like; this, I just kind of landed upon. But I’ve been looking for this sound, internally, for a long time, almost 12 or 13 years. It just didn’t hit me until now. This concept of war drums and samples of my favorite recordings…the whole thing is a study.

Most of the music you’ve done in the past has been performing with groups, and it’s interesting that an idea like Technoself came from your first solo project. Can you talk about the dynamics of working in a group versus working by yourself, and how that helped evolve the idea?

I’ve had tremendous experiences with groups and ensembles. I’ve worked hard to be a team player—so naturally I’ve always wanted to go to the opposite end, and see what I could create on my own. And that is really the center of this whole thing. The idea of Technoself is the group being yourself, and looking at your body as all these different members. For me it’s looking at those components, and realizing that I can be my own ensemble.

Could you talk about some of the ideological influences versus the sonic influences?

Hearing [J Dilla’s] Donuts—the freedom in the way that he samples, as compared to most of the other modern day programmers—really inspired me. I think J Dilla paralyzed the production game with that record; it was so free and just wasn’t contrived at all. I wanted to make a record that can exist after Donuts, because I don’t know how many records that can. Also, working closely with John Cale really had a major effect on me and kinda made me free up and think about things differently. So it’s a direct result of those things together.

What was it like to work with Cale?

He’s more of an influence on this record than anyone. I’m doing this with the kind of attitude that I could only get if I had the respect of John. Wherever I would go, I always came back to John, he was always there. John is just such a force of ideas and curiosity. He gave me confidence in my work, and you need that confidence to be great. I’ve always had these things on the inside, but he helped me externalize.

What’s Sade like?

It’s weird because they’ve been a band for so long. They don’t have outside people come in. I worked with Stuart Matthewman, their guitarist, for a while. He was a supporter of my music, and was trying to introduce me to Sade for years, but it never happened. I thought he was just being nice—and then finally an opportunity came up when she did the Solider of Love album; they were playing the album’s title track on David Letterman’s show. Coming in, I had no clue what to expect from Sade herself. The music we were doing was unbelievably simple and easy, I thought we were gonna run it once. No. We rehearsed that song over and over again. We were rehearsing that simple pop song—everyone plays the same thing every time, but she was being so knit-picky. And I loved it.

Support Independent Media

Music, in-depth features, artist content (sample packs, project files, mix downloads), news, and art, for only $3.99/month.