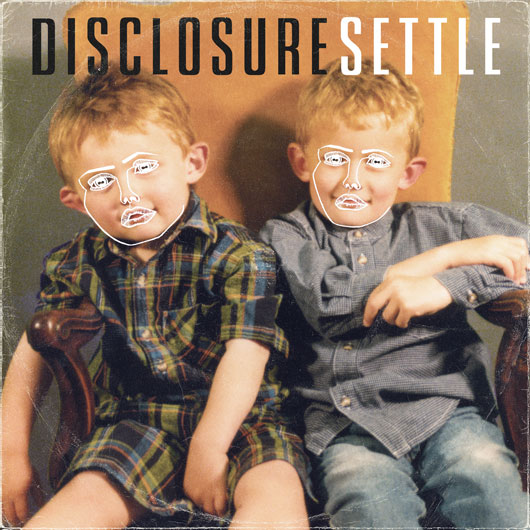

Deep Inside: Disclosure ‘Settle’

Any discussion of Disclosure, the English duo of Guy and Howard Lawrence, seems to be […]

Deep Inside: Disclosure ‘Settle’

Any discussion of Disclosure, the English duo of Guy and Howard Lawrence, seems to be […]

Any discussion of Disclosure, the English duo of Guy and Howard Lawrence, seems to be fraught with controversy. The pair released its first single while the brothers were precocious teenagers (Howard is still yet to reach 20), and has followed it with a catalog that combines a whole history of underground dance music with the hookiest contemporary pop. This irks a lot of people. Common critiques maintain that the brothers are either too young to fully appreciate their influences (though growing up near London surely helped to accelerate their maturity), are perverting them via streamlining, or both.

These are of course underground frustrations, ones based at least in part on the pop world’s lack of frustration. While partly valid, these claims ignore the history of past club music-to-pop crossovers—acid house’s “summer of love,” for one, saw experimental Chicago tracks reinterpreted in New Order’s chart-topping singles and massive British raves alike. Disclosure is merely another part of this lineage, and from an “underground” standpoint, it is better to maintain indifference. They are a pop act through and through, and there is really no solving the “problem” of Disclosure, other than to perhaps acknowledge that underneath the sheen, there are occasional flashes of eccentricity.

Settle, the duo’s debut album, confirms the project’s pop ambitions. In conversation, Guy is disarmingly lax about the pair’s process. In a way, he has the air of a super-producer, the sort who might appear on YouTube composing a ubiquitous, million-dollar single in a matter of minutes. “Ninety percent of the time it’ll be like, I’ll be producing a beat and getting an idea going, and then Howard will be with the singer coming up with a theme for the song and the lyrics, and just throwing ideas and melodies around,” he says. “With a song like ‘Latch,’ we actually had the whole song finished and written, but it had samples all over it. It had no lyrics or anything—it was all cut up, with vocals from an old house track. And then in the studio we cut all the samples off, and just put [Sam Smith] on it instead. That was the only song where we started with a vocalist that was already complete, if you know what I mean. [On] ‘White Noise,’ we had nothing at all. When AlunaGeorge came into the studio we were like, ‘we’ve been on tour for a month, we’ve got nothing for you, what do you want to do?’ A couple of days before I’d made a little bassline, or a little melody, and that was it. She was like, ‘I really like that,’ so I just put some drums under it and we went from there. It varies every time.”

Guy describes Disclosure’s “only brief” for the album as being “a nice mixture between pop-structured songs with vocals and instrumental club tracks,” and in fact the record does just this, pairing an array of collaborations with trackier, more purpose-built material. Still, there are some basic similarities—pitch-diving melodies, hollowed-out basslines, perky rhythms situated between tech-house and UK garage—that unite these sides. Whatever the brothers’ ambition, the album’s sameness is a testament to how closely pop, at least in the UK, is aligned with dance music. Settle hints at unconventional (for pop music, anyway) moves in a couple of places. “When A Fire Starts To Burn” is underlined by a barreling melody that is a bit Detroit techno, while “Second Chance” is of a piece with the spacious, choppy pop that has sprung up in Mount Kimbie’s wake.

Overall, though, the LP is marked by its collaborators. The result is less about Disclosure making a statement than a “producer” album, an effort featuring a hodgepodge of cuts that only sit together by virtue of their producers’ tendencies. There was “no set formula” to the eight collaborative cuts, but there was a hands-on aspect throughout the recording process. “We always make sure we’re with the singer every step of the way, whether they’re writing vocal lines or lyrics,” Guy says. “We never send dubs or things like that to people; we don’t really like working like that.” Settle is clearly a selection of tracks that have been honed by the brothers and singers alike, and as a result, the vocals are able to breathe, free of processing. “We’d already chopped up vocals two years ago,” Guy recalls. “I don’t think we need to prove to anyone anymore that we can do that. I still like all that stuff, but we always want to push ourselves and we just thought [that] for the album, writing songs with vocalists made more sense. I don’t think we ever had a conversation, we just kind of knew that we wanted to do it like that.”

Although Howard works on the lyrics (both in collaboration with the guest vocalists and on the songs he sings himself, like “F For You”) more than Guy, the older brother maintains that there is often little behind them. The brothers might attempt to shift pop paradigms by inserting dance-music reference points, but they further the age-old tradition that a hook can be about virtually anything. “The things that the songs are about are not always what they appear. With ‘F For You,’ for example, it sounds like [Howard] is being a fool, like it’s a love song. But it’s actually about him being infected with a cold,” Guy reveals. “A lot of the songs I don’t really know the meaning myself, to be honest. [Some] are love songs. A lot of the songs don’t have much meaning at all, like ‘January,’ featuring Jamie Woon. That’s just a song about stuff. ‘Twenty-second of January’ is the main lyric, and it’s like, nothing actually happens on the 22 of January. It’s not a special day for us at all—it just sounded good in the song.”

This might all be fuel for the anti-Disclosure fire, but Settle is at least commendable for its unabashed, upfront sensibility. As a collection of pop tracks, it surely succeeds. To judge it on a deeply artistic basis seems to miss the point, as this was never the brothers’ ambition—it is really more of a compilation than anything else. Although Guy insists that the two have no formula, it is clear that they have plenty of grasp on what it takes to make a radio-ready single, and this is truly the focus—it’s just done over and over again, with slightly different singers and arrangements. Guy mentions that he would love to eventually write a record with a thoughtful, narrative scope, and cites Kendrick Lamar’s recent good kid, m.A.A.d city LP as one of his favorites. But for now, he says, “it’s quite a tall order. I don’t think we’re quite good enough!”