Deep Inside: Drexciya ‘Journey of the Deep Sea Dweller II’

There’s only a handful of artists that can justify a four-part series of full-length reissues: […]

Deep Inside: Drexciya ‘Journey of the Deep Sea Dweller II’

There’s only a handful of artists that can justify a four-part series of full-length reissues: […]

There’s only a handful of artists that can justify a four-part series of full-length reissues: Elvis, Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, and (of course) Drexciya. Even though pretty much no one would agree with that statement for various reasons, you have to admire Rotterdam’s Clone Records for knowing exactly what they like. Journey of the Deep Sea Dweller II is the latest in Clone’s Drexciya retrospective, and like the first edition, Journey II takes songs from the Detroit band’s 10-year existence (1992 to 2002) and builds a tremendous case as to why its singular “techno from the deep” is more relevant now than ever. If electronic music’s sea of genres has dissolved into a sea of icononclasts, Drexciya populated those waters first.

Even at its peak, Drexciya was never a likely candidate for wide popularity—its music was too hermetic and weird, falling somewhere between punk and Kraftwerk funk via 808 drum machines and flickering, diminished chords. The personalities behind Drexciya didn’t help much, either: founding member James Stinson purposely isolated himself from Detroit’s techno scene, while proclaiming the evils of Richie Hawtin’s exploitive “Caucasian Persuasion” in Melody Maker. Meanwhile, Stinson’s partner, Gerald Donald, was fascinated with black fascism and technological eugenics; his other aliases such as Dopplereffekt tried to sneak in SS insignias on label art, paired with lyrics like “we had to sterilize the population.” These were not exactly the moves of careerists, let alone torchbearers for Detroit’s techno scene.

Donald’s SS pin blacked out on the collar

Drexciya’s anti-social waterworld was sealed away, disconnected from the party. The duo didn’t seem to take in new influences, but rather fed off the ghosts of old ones. Juan Atkins and Kraftwerk obviously loomed heavily, along with dark disco and P-Funk. But Drexciya was too individualistic to make copies, its music carrying the DNA of early electro and techno, but with the extravagance of pop song structure stripped out. In its place was a comic-book world called Drexciya, where Darthouven Fish Men and Neon Falls were described like rippling animations.

In classic comic-book style, Journey II begins where the first compilation’s “Dehydration” ends: with a security checkpoint sequence in the form of “Intro,” where an ominously pitched-down vocal declares, “Welcome to the fusion zone.” From there, song titles move in a chronological adventure—from the surface waves of “High Tide” to “Danger Bay,” whose underwater “Ha”‘s sound like some kind of Drexciyan warning before approaching the clearly dangerous “Anti Vapour Waves.” Journey II‘s sequencing speaks to Clone’s obsessive engagement with the Drexciyan myth—there’s some filler on the album, but it serves this particular quest’s story arc.

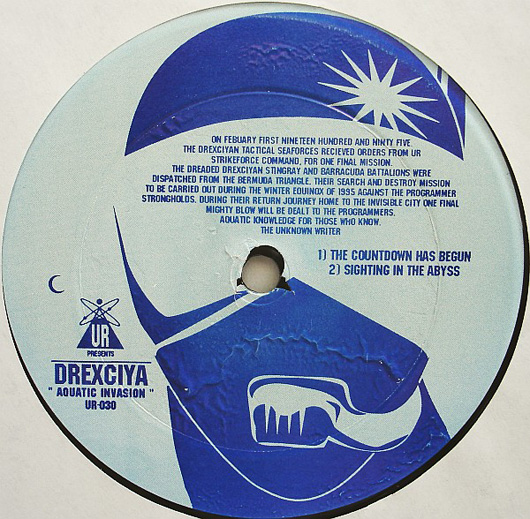

Coverage of Drexciya has always tended to fixate on specifics of the band’s underwater world, further playing up the idea that no one knew who they were until James Stinson’s death in 2002. While it’s cool to imagine that was the case and it certainly fit with their underwater concept, the members of Drexciya weren’t complete masterminds of their destiny. Militaristic narratives by “The Unknown Writer,” found on Drexciya’s three records for Underground Resistance, seem slightly out-of-character in retrospect—as if Drexciya was adapted to fit UR’s agenda. Likewise, the band’s compilation The Quest on UR’s Submerge label suggested the mysterious Drexciyans were descendants of pregnant African women thrown overboard during the Middle Passage. These were fascinating ideas for sure, but the music itself never really addressed them. Drexciya was too playful for Terrordome-style confrontation; see “Bang Bang” for further proof.

“[Drexciya is] not really in disguise” Stinson told Liz Copland on Detroit Radio, a couple of months before his death in 2002. “It’s just more or less given us our own territory, it’s more about being isolated to where you can go about your own daily business… and not really be involved, like an isolated community. If you look at some of the other documentaries about undersea life or whatever it just looks so peaceful down there, beautiful, no sunlight, total darkness.”

For Drexciya, deep sea’s isolation was a creative trick as much as a narrative one. In their attempt to document the Drexciyan deep, Stinson and Donald created a world that was essentially a series of constantly evolving, conflicting, and unfinished vignettes. None of it ever really made sense, but it didn’t matter because Drexciya was best at invoking a vibe; its sound was more suggestive than literal. Listening to the music can be like hearing a Rorschach test: the diffused ripple of voices and swirling high hats on “Danger Bay” personally recall the experience of treading right on the edge of water and air; the droning bassline on “Anti Vapour Waves” clings to the sea floor like a drifting underwater vessel dodging jagged reef.

“We don’t make songs based on a concept,” Stinson told the Detroit Free Times in 2002. “We make the songs first and deal with the concept around the songs. After the music is created, we’re building a concept around it: moods, emotions and feelings from the music helps build [that]. Basically, what we do is listen to the record and then your mind starts to wander and images come to your mind. Hopefully, people that buy the record feel the same thing. When you listen to the music and read the title, you basically have to run with it. The images have to go with the themes.”

As boundless as the water imagery was, the actual methods behind the music were considerably more terrestrial. “We do everything freestyle” reads the declaration on the one-sheet for The Journey Home EP. “We program as little as possible, and the little we do program, we manipulate as much as possible.” In other words, Drexciya tracks were the product of jamming—something that’s not hard to believe given the tiny mistakes and oddly phrased arrangements that litter most of the group’s songs. Recorded straight to a Tascam 4-track with no computer edits, Drexciya’s looseness sounds thrilling next to most electronic music made today; it’s unpredictable, raw, and very much analog. The remastering job of Journey II does little to “repair” that; Clone’s Alden Tyrell didn’t go back and fix the 13-bar intros for easier DJ use, nor did he crush the mix.

Brendan M. Gillen of Ectomorph recently called Drexciya the techno equivalent of Syd Barrett and Daniel Johnston, “actual mentally disturbed individuals” whose identities became lost within their music. It’s an apt comparison. For all intents and purposes, the members of Drexciya lived in their underwater world, and their sound was totally unmistakable as a result. Newer artists can (and have) copied the trivial parts of Drexciya’s sound, biographical smoke screen, and “lo-fi” production technique. But it’s not enough—you have to go too deep first. It’s Drexciya’s world, we’re all just visiting.

A huge thanks to the Drexciya Research Lab, which has compiled the most complete archive of Drexciya information available, in addition to updates on Gerald Donald’s many projects.