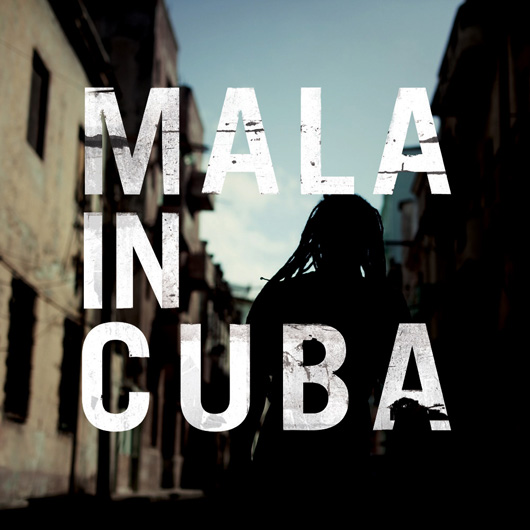

Deep Inside: Mala ‘Mala in Cuba’

Cuban music plays heavily with percussion and goes mental for melodies, but rarely does it […]

Deep Inside: Mala ‘Mala in Cuba’

Cuban music plays heavily with percussion and goes mental for melodies, but rarely does it […]

Cuban music plays heavily with percussion and goes mental for melodies, but rarely does it meditate on bass weight. By contrast, British producer Mala (of Digital Mystikz/Deep Medi fame) has spent nearly his entire career experimenting with the way bass, sub-bass, and drums can work together to rattle minds and stoke dancefloor fires. On Mala in Cuba—a collaboration between DMZ’s proud lion and traditional Cuban musicians—live instrumentation is incorporated within a loose dubstep framework, but Mala keeps a firm hold on the reins. Rather than trying to match the lively, uptempo energy of the Cuban sounds, he envelopes Latin elements in a thick London fog, pulling melancholy from beneath tinkling ivories and adding mystery to reverbed salsa rhythms.

Though Mala went to Cuba to make the record—at the urging of Brownswood label head Gilles Peterson (and as part of his ongoing Havana Cultura initiative)—he didn’t do much writing or arranging there. Rather, he played skeletons of 140 bpm beats to musicians, including Robert Fonseca and his band, singer Danay Suarez, and percussionist Changuito. The players freestyled over the beats, with Mala and an engineer capturing every nuance via tape into a top-of-the-line SSL mixing desk. “I came home from Cuba with about 60 gigs worth of live playing,” he recalls. “It was just so much information to process and to go through. The level of musicianship was phenomenal—so good, it made me feel very uncomfortable and inferior. I don’t understand music in that way. Ask me to hum a C or a D and I can’t do it… but I will hear a C and a D and feel it. I just had to make music how I feel it and this is how it came out. I can only bring what I do, so I guess the record is really me trying to translate my experience of Cuba.”

Perhaps to the dismay of the serious steppers out there, there are times when this record feels just like Mala sending you a postcard from Havana. It’s written in his voice, but the scenes are distinctly pastel and totally tropical, hazy memories of whitewashed churches and street-corner conga jams. “The Tourist” saunters like a pair of faded madras shorts around a dusty square at high noon, sunny strings reverberating from a nearby alley, shakers and güiras galloping at the pace of horses hooves. “Como Como” and “Changes” blaze with a contained but palpable energy; the former with the tangerine pulse of a highly caffeinated cortado hitting your morning veins, the latter a liquid pink sunset shot through with breezy blue piano echoes, slowly building to the anticipation of nightfall in center city.

But Mala’s not really that comfortable being a tourist—no matter what country he goes to, he’s going to be the guy standing in shadows of the club, taking it all in. It’s this deep thought and an almost Shaolin-like minimalism (plus the aforementioned “bass weight”) that’s made classic tracks like “Bury Da Bwoy” and “Anti-War Dub” reverberate far outside the hermetic South London environment in which they were made. In similar fashion, the most interesting tracks on Mala in Cuba abstract and absorb Cuban percussion as a means of finding new ways to ride his signature rhythm. The smoky purple salsa of “Mulata,” the hardcore-refracted swell of “Revolution,” and “Ghost”—a mesmerizing ebb and flow of pensive pianos and layer upon layer of tribal handclaps nestled in a sea of elemental low end—contain that inimitably haunted and dubby Digital Mystikz touch. They are a postcard from a country that doesn’t exist; missives from an emotional hyperspace between sea and sky, soundsystem and studio.

Having sampled numerous reggae, jazz, and soul records, Mala is no stranger to the appeal of organic sounds—indeed, he’s thought to be one of the few keeping the word “dub” in dubstep. But sampling is a far cry from working with live takes, which Mala says revolutionized his view on music-making. “I’ve grown up playing computers, Nintendo, Playstation, Sega. For me, it’s all about that: electronics behind the computer. I didn’t necessarily think it was important to incorporate live music into the style of music that I make, but having done so, it’s totally changed me. You know those optical illusions where you look at something but you can’t see it? And then all of a sudden your eyes focus and you can see the image. That’s almost what it’s been like for me. What these musicians do is something that can’t be recreated—it can be recorded, but even the recording isn’t the real thing. I don’t think I can ever go back. The whole process of making this album has totally changed my thinking and the way that I will approach making music in the future.”

The process of making dance music can be overtly mathematical, but the source material here encouraged Mala to move farther off the grid. “Some of the grooves, especially the in-between grooves, I left unquantized,” he recalls, “especially the congas and the timbale. This guy came in [to record] called Changuito. I don’t know how old he is but he walked into the studio like such a don: white Kangol, pink shirt, he had this chain on and his arm in a plaster caster. He set up his timbale and just started playing over the beats I had made. When I was making that album there was always a time where I was like, ‘Ahh, it’s missing some stuff! I need to add something.’ I forgot I had all these Changuito recordings. And I would just lay him on it and I didn’t even have to quantize it. The way he would fit in between the grooves! You can’t create that. It has to be somebody doing it. With that human element, there’s an energy, there’s a spirit, there’s a being behind it. All these things have been stored in the milliseconds of sounds that make up the entire track. If you would have asked me this a year ago, I would have said it maybe it doesn’t matter, but actually I think I understand the difference now.”

There’s no cool way to say this, but Mala in Cuba is a mature album. Some will see it as an open-minded victory in the war against the current wave of wobble-and-drop-obsessed dubstep; others will take it as evidence that Mala’s forsaken the dancefloor. (Though, to be fair, he’s known for playing fast and loose with anything coming close to a dubstep formula.) What is clear is that Mala is one of the only people in his genre who could pull off such a fusion and keep it from sounding forced, in part because he is not always preoccupied with making the club shake.

“When you get to being 32, you can actually have a conversation with people that you couldn’t have when you were 16 years old. When you’re 16, 17, 18 years old, you just wanna go out and ‘ave it. Everything has changed in my perspective now. I still love tearout music, I love hard music, I love music that makes me freak out and want to just skank out. But on an energetic and on an intellectual or spiritual level, when I’m sitting at home alone in my studio, I’m not trying to have a rave anymore. I’m trying to make music for my environment that I’m in.”

“I can listen to something extremely gnarly and aggressive but when that inspiration makes me create, it’s never going to come out that way,” he continues. “But it doesn’t mean that the two things can’t coexist in harmony; something extremely ravey and tear-out can be alongside something that is deep and meditative. Ultimately, it’s all the same thing. It’s all frequencies that we’re manipulating.”

Though there’s nothing as resolutely ravey as “Eyez” on here, rolling and dubby drum workouts “Cuba Electronic” and “Changuito” and “The Tunnel,” with slinky technoid bass that’s simply cobra-deadly, are sure to nice up sophisticated dancefloors. Mala’s rep is built on his deeper flavors, so it’s easy to forget that DMZ (the label he runs with longtime friends Coki, Pokes, and Loefah) was a dance organization first and foremost—Mala has arrived at this point in time and space by traveling through the continuum of rave music.

“I’ve always felt it’s important just to follow what it is that you do,” he explains, telling the story of how he started as a jungle MC at the age of 14. Under the name Malibu, he and his partner Coke (now Coki) and their friend Poker (a.k.a. Sgt. Pokes) would play under-18 parties every week, chatting over sets from legendary DJs such as Kenny Ken, Jumpin’ Jack Frost, and DJ Rap. By the time he was 17, Malibu had moved into MCing in the UK garage scene, though it became clear to him that he wasn’t cut out for its consumerist leanings. “I didn’t like the bling-bling, I wasn’t about all the champagne drinkin’ and all that. The lyrics I used to say were on a conscious vibe but people in that scene didn’t want to hear no reality—they wanted fantasy and entertainment. I always felt like a bit of an outcast.”

Nevertheless, he landed a record deal for his garage MC skills. “As a 19 year old, when a major label comes to you and offers you x amount of money and says, ‘This is the shit,’ you build your life’s dream on it. And that’s what I did, you know. We got signed to EMI and they took the piss. You understand what the majors are about—they’re about money, business. They don’t care about personal development, they don’t care about your dreams. If they don’t see a quick return, they drop you. It was madness, madness, madness to experience it, but it was an absolutely crucial learning experience because it made me realize that is not for me.”

“I got really depressed and that’s when I really started channeling my energy into making music. I locked off the whole MCing thing because I had nothing more to say. Then it was like, ‘How can I connect with people?’ Alright, I got rid of the words. Now, let’s just deal with sound. And that’s when I started making music.”

These experiences have also made Mala notoriously careful about what he puts out and who he gets involved with, rarely releasing anything outside of his DMZ or Deep Medi camps. “I’m very militant in some ways in the way I like to go about doing music,” he admits. “I just work on stuff on my own and I put out stuff quite quietly.” But when Gilles called last year with an offer to go to Cuba, something about the timing seemed to dovetail with Mala’s own musical path. “I was slightly apprehensive [about this] because it was blatantly out of my comfort zone,” he says, “but it just felt like a really genuine offer and something that I probably shouldn’t pass up.”

“I felt really at home in Cuba, I really did,” Mala continues. “The people I met [there] do music for the same reason I do it—because they love it. They don’t do it because they think they’re going to be successful or famous, they just do it because its something within them that they have to do. That’s the beautiful thing for me about all of this. It’s not about finishing music or being able to sell a record. It’s just really about exploring and discovering new things. For me, that’s really where the joy is in all of this.”

Mala in Cuba is out now on Brownswood.