Electro Everlasting

Is there such a thing as an “electro revival” or did we just not notice how relevant it's always been?

Electro Everlasting

Is there such a thing as an “electro revival” or did we just not notice how relevant it's always been?

Is there such a thing as an “electro revival” or did we just not notice how relevant it’s always been? Tracing the music’s history and effect, Marc Rowlands argues that its continued presence and pivotal influence negate the need to ever announce a revival. Helena Hauff, Radioactive Man, Neil Landstrumm, Skam, CPU, Sync 24, Solar One Music contribute.

Amid the lights, smoke, and bodies on the dancefloor, the music’s tempo does not falter as the rhythm changes. A few fail to adapt. Their on-the-spot marching is interrupted by an irregular new beat, its bass double punching the stomach at the end of the bar. For them, it’s one blow too many and they fall by the wayside. For others, though, their bodies come alive; their feet add an extra shuffle, an extra bounce, as they skip to a near breakbeat. Their shoulders drop as they weave in and out of the groove while psychedelic synths and robotic vocals ride atop the restructured yet still ruthlessly regimented rhythm.

Ever since the early 1990s, when it was first heard on techno dancefloors, electro has been dividing opinion. It has fallen in and out of favor within alternate sections of the same club audience in a similar manner to how it has faded from view, then resurged perpetually, since its early ‘80s birth.

Currently, it would seem that electro is experiencing yet another of its moments in the spotlight: multiple media outlets have announced a “revival” and showered attention on DJs and producers within its realm. The stock of both newer entrants such as Helena Hauff and also vintage purveyors like Egyptian Lover and DJ Stingray has never been higher. And the sound has become increasingly noticeable in the sets of such DJs as Steffi, Paul Woolford (as Special Request), Nina Kraviz, Ben UFO, and Maceo Plex.

DJs like Craig Richards and Surgeon have been incorporating electro into their sets since it first found common ground with techno in the ‘90s. For long periods, electro and techno had been disparate; only when DJs like Dave Clarke, Billy Nasty, Surgeon and others started playing Detroit electro did this begin to change—much to the annoyance of some dancers, frustrated by the loss of the regular 4/4 rhythm.

Nonetheless, this alignment of the genres in the mid-‘90s helped to inspire a wealth of contributors at post millennium labels like CPU, Brokntoys, Cultivated Electronics, Stilleben, Shiprec, Bass Agenda, WeMe, Solar One Music, Houndstooth, Asking for Trouble, The Nothing Special, and others. Many behind such labels attest to a 1990s start point of their electro embrace. Their own releases are now furthering the genre, fuelling current talk of a revival.

However, alongside these comparative newcomers to electro exist names like Aphex Twin, Carl Finlow (a.k.a Random Factor and Silicon Scally), Keith Tenniswood (a.k.a Radioactive Man), Anthony Rother, DMX Krew, and Neil Landstrumm, whose education in electro extends beyond a mid-1990s introduction.

In examining the integrated lineages of such artists and labels, and the influence they’ve had, it is impossible, not to mention disrespectful, to herald any manner of revival. It is arrogant to even suggest such. Because electro is a constant presence. Electro has many times altered the course of modern music, whether that be its under-acknowledged fuelling of IDM, setting the blueprint for Miami Bass, or helping cement Detroit’s techno-era reputation. It also changed the sound of hip-hop forever.

Irrespective of the fads, fashions, and understanding of the mainstream and the media, electro is a fundamental and ceaseless modern musical movement. Only in their eyes did it ever fade from relevance or view. Only as a result of believing such a warped perspective could someone like DJ Stingray now be experiencing a high point in his career, for he has trodden this same path for over 20 years. This revival is an artificial media construct born of ignorance. In truth, when you trace this music’s journey from the start, it’s obvious to see that electro has always been with us and always been relevant.

The Dawn of a New Era

“I can remember being a kid and seeing my mum dancing around and singing to “The Model” by Kraftwerk,” recalls Keith Tenniswood, who began his career in the mid-‘90s as part of Two Lone Swordsmen alongside Andrew Weatherall, and has produced offbeat electronica, much of it electro-influenced, ever since. “When I was about 11, the whole thing exploded. It was like going from a black and white film to glorious technicolor for a kid that age; the whole breakdancing/body popping thing, DJ’s cutting and scratching, and colorful graffiti. Post-punk and some of the new wave, that was fairly boring to us. That was something your elder sister might have liked. The new electronic sounds and rhythms were really just mind-blowing.”

British new wave and synth pop arrived at the dawn of the 1980s and in this new synthesizer use lay an indication of exciting possibilities. Potential. But much of their songwriting was in a staid, familiar format, as was the rest of their instrumentation. And some of these guys dressed like pirates, 18th-century dandies or, worse still, in pastel shaded suits with shoulder pads. How could kids even relate to that? Not cool.

But something very cool was about to arrive: hip-hop. “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979 heralded this arrival. But it wasn’t until Blondie’s “Rapture” in 1981 that it received its first widespread recognition, Debbie Harry’s rap being the vocal style’s first number one hit.

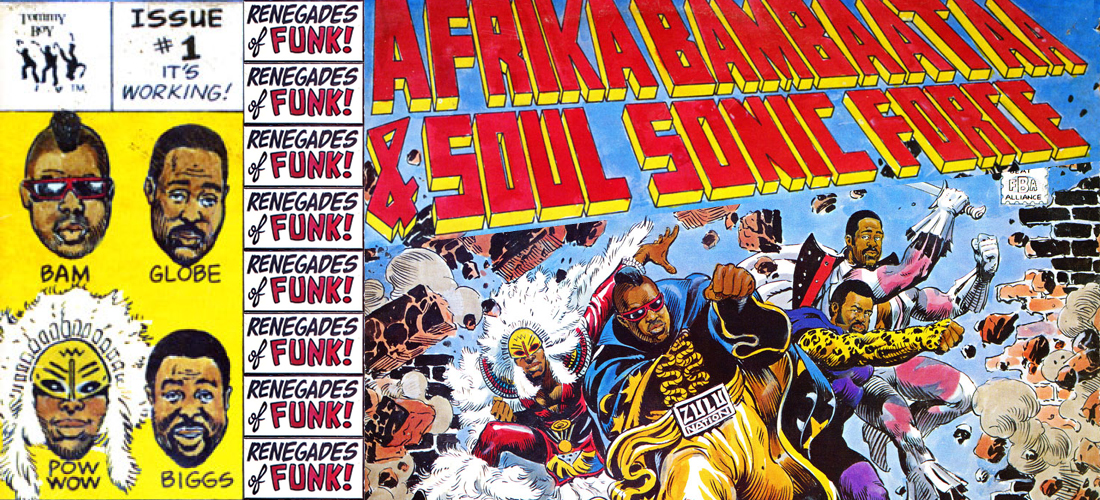

Yet, despite unleashing a new style of music (and art) on the world, “Rapture,” “Rapper’s Delight”—and also Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks”—were essentially just familiar sounding disco tracks with a fresh style of vocal delivery. It wasn’t really until 1982 that the 1980s truly arrived. The new era’s music was announced in April with the release of “Planet Rock” by Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force. It was a radical departure from the disco-based hip-hop sound, a single like no other that preceded it and one which would influence countless musics to come.

Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force

“Planet Rock” did not sound wholly unfamiliar, yet its effect was profound. Its beat pattern and melody were reproduced from Kraftwerk. The electronic sound of latter-day P-Funk like Zapp’s “More Bounce To The Ounce” had also set a template of sorts. But with “Planet Rock”, Afrika Bambaataa, producer Arthur Baker and keyboard player John Robie, had created something entirely different. And in doing so, they far exceeded previous templates.

The release saw funk music’s “on the one” (where the bassline and kick drum occur on the first beat of the bar) delivered via the fresh, brutal Roland TR-808 drum machine, providing the rhythm with a radical and powerful new sound. The combination of robot-like vocoder and rapped vocals placed the song simultaneously within both the future and within the here and now of New York’s bubbling street culture. The song was an immediate hit, going on to sell well over half a million copies. It was an anthem for a new era.

Prior to 1982, the future had seemed like an unreachable fantasy, set a in a galaxy far, far away. But in 1982, new economic ideas were entering society. Technologies like the home computer—unthinkable in the decade previous—were now at immediate hand. The possibilities seemed endless. The future soundtracked by “Planet Rock” was one that seemed to share the dark, dystopian backdrop of 1982’s Blade Runner and Escape From New York, one which mirrored our own inner-city streets. The future was suddenly not only believable but present.

Planet Rock’s success immediately spawned imitations. Man Parrish “Hip Hop Be Bop”, Warp 9 “Nunk”, The Packman “I’m The Packman (Eat Everything I Can)”, Extra T “E.T. Boogie”, The Jonzun Crew “Pack Jam”, Whodini “Magic’s Wand” and Planet Patrol “Play At Your Own Risk”, to greater and lesser extents, all followed Planet Rock’s blueprint before the year’s end. Electro was born.

The new sound was adopted immediately, not least in the UK. Thanks to electro, fashions, and dance styles seemed to change overnight. B-boys everywhere adopted New York street fashion, shunned everything that preceded the new music and dedicated their time to practicing the body-popping and break dance styles that accompanied the new sound. Within a year, the genre even had its own UK compilation series. “My first memories of electro were those compilations you got in Woolworths for 49p, Streetsounds Electro 1, 2 and 3,” says former b-boy Neil Landstrumm, who has produced techno and electronica of hip-hop, dubstep, and electro inspiration since the early ‘90s. He explains that the electro era was a refreshing change from the “long trench coat moodiness” of new wave and synth pop. “The style of it was everything,” he adds.

Electro: Hip-Hop Changes Forever

As much as “Planet Rock” had set a blueprint for the rest of the emerging electro records, its revolutionary sound had just as big an impact on hip-hop. In 1982, on Sugar Hill Records, The Furious Five ditched the live drums and disco sound, opting instead for drum machines and synths. In dropping the tempo and creating the first socially conscious rap lyric, with “The Message” they managed, just a few months after “Planet Rock,” to birth modern and meaningful hip-hop.

In Harlem, The Fearless Four trod a similar path with “Rockin’ It.” Its lyrics weren’t as revolutionary as “The Message,” but it again was built around a drum machine, synths, and a Kraftwerk sample (The Man-Machine). By 1983, Run DMC had arrived with a visual identity as streamlined as the sparse, drum machine-heavy backing they rapped over. Although many adopted the newer Roland TR-909 (released 1983) over Planet Rock’s 808, it was still the stark, brutal, and shocking drum sound that Afrika Bambaataa and co had introduced. It became the backbone of mid-1980s hip-hop.

Looking For The Perfect Beat

Although many tried to follow Planet Rock’s lead in 1982, such was the thirst for the new electro music that demand exceeded supply. B-boys who’d spent half their week practicing their breakdancing and body popping no longer wanted other musics interrupting their new dancefloor obsession; they wanted the new sound to last all night. Given this shortage, DJs were forced to flip over soul and disco cuts, which shared similar drum machine and synth elements to electro, and play their instrumentals. Tracks like C-Bank “One More Shot,” Klein MBO’s “Dirty Talk”, Xena “On The Upside,” and D Train “You’re The One For Me” are all classic examples. The obsession with electro had necessitated a complete change in what DJs had to look for in a record.

This change in perception had also caused a re-evaluation of music in the eyes of youthful music lovers. Could it be coincidence that 1982 also saw Kraftwerk score their first UK number one, with a song that had originally been released four years earlier (The Model)? Perhaps their groundbreaking techno-pop had sounded too advanced for many UK ears until the future was claimed in 1982? (Or maybe it was just that the original had been in German).

In 1983, the expansion of electro continued apace. Shannon “Let The Music Play,” Herbie Hancock “Rockit,” Newcleus “Jam On Revenge,” Capt. Rock “The Return Of Capt. Rock”, Hashim “Al-Naafiysh (The Soul)” all became (enduring) hits. The sound proved so popular that it left its New York boundaries and people like Egyptian Lover, Unknown DJ, and later the World Class Wreckin Cru helped to kick off an electro scene on the West Coast (the latter also playing a part in birthing the careers of Dr. Dre and other members of NWA).

But nowhere could the template of Planet Rock be more directly recognized than in the scene built from the mid-‘80s in Florida. Miami Bass was a subgenre founded entirely upon the record, a subgenre which proved to have a long-lasting popularity and an influence all of its own. In its strict adherence to Planet Rock’s fundamental principles, Miami Bass is perhaps the single greatest testament to the importance of that one song. Back in New York, in a fearless move that proved they were no one hit wonders, Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force themselves refused to follow their own blueprint. Instead, they innovated again with two brilliant and distinct releases, “Looking For The Perfect Beat” and “Renegades Of Funk.”

Detroit Enters The Game

The electro scenes in Miami and on the west coast were among the earliest to be recognized outside of New York. But achievements in an altogether different territory went on to eclipse them. The first electro track emerged from Detroit in 1983.

Partnered with Vietnam veteran Rick Davies (a.k.a 3070), Juan Atkins formed the electronic group Cybotron in the early ‘80s. Their first two self-released singles are accredited, alongside A Number Of Names’ “Sharevari,” with birthing Detroit techno. But on their third release, “Clear,” Cybotron entered the realms of electro. In doing so, they laid the foundations for what became an inextricable link between the emerging machine music of Detroit and the electro sound of New York. This link would go on to be strengthened with repeated forays into electro by the biggest names in Detroit techno, so much so that by the ‘90s, Detroit had all but assumed ownership of the electro genre. These musics shared more attributes than just their Roland TR-808 drum sound: both were futuristic; both had the funk.

In 1983, Cybotron released Enter, their collected works in album format. It is a landmark collection of techno’s first steps, and with the inclusion of “El Salvador,” the group reaffirmed that electro was to be a part of this sound. This was followed by a string of underground Detroit electro releases through the ‘80s like The Cosmic Population “Modulation” (1984), Nu-Sound II Crew “The Speed Of Light” (1986), Night Mares “Elreta” (1986), and Channel One’s “It’s Channel One” (1987). Electro even proved to be the entry point for some of Detroit’s future stars. On electro release Nasa Time To Party, Scan 7’s Lou Robinson, Urban Tribe’s DJ Stingray, and 3 Chairs member Rick Wilhite were all given their debut.

Meanwhile, in New York, as the ‘80s progressed, the sonic advances made by electro were being absorbed into other musics; funk, disco, soul acts like Mantronix and not least hip-hop. But in Detroit, the pure electro sound had taken hold.

Detroit Takes The Mantle

Juan Atkins himself continued to mine the electro sound through the 1980s, not least with the debut Model 500 EP No UFOs/Future (1985) and as Audio Tech with I’m Your Audio Tech (1987). Electro was also a key influence on Detroit’s emerging techno personas like Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, Eddie Fowlkes, Carl Craig, Blake Baxter, James Pennington, and Jay Denham. These were the artists who established “Detroit techno,” though that labeling, ascribed largely by European music journalists, proved initially discomforting to some of Detroit’s protagonists. Nevertheless, Detroit’s machine music was different from that of their Chicago peers. Could this not be at least partly attributed to the influence of European electronic sounds like Kraftwerk and Detroit’s dark, enduring electro scene?

Around the dawning of the new decade, Motor City 12”s offered up several new names who played an important part in consolidating Detroit’s appropriation of electro. 1990 saw the first releases by Mike Banks and Jeff Mills as Underground Resistance on a label bearing the same name. Also, the debut releases of brothers Lenny Burden and Lawrence Burden as Octave One on Transmat.

Such was the combined creativity of these and other new players on Detroit’s techno scene that the three most established labels, Atkins’ Metroplex, Saunderson’s KMS and May’s Transmat, just could not keep up. Like Underground Resistance, the Burden brothers (along with another of their siblings) decided to form their own label.

The Burden’s 430 West proved to be a key outlet. Ethically well ran, it released not just their own music (under a variety of aliases) but also that of people like Eddie Fowlkes, Jay Denham, Terrence Parker, and Anthony Shakir. Just two years into its life, 430 West released a 12” by a group called Sight Beyond Sight. Among the bold advances of Detroit’s then catalog it was pretty unremarkable. But when two of that group’s members, Tommy Hamilton and Keith Tucker, reconvened as Aux 88, something remarkable did happen.

In 1993, the Burden brothers launched a sub-label specifically for a more raw, street edged sound than that of 430 West. They named it Direct Beat and it became Detroit’s first label dedicated to electro. With its second release Technology, Aux 88 were introduced. The group swiftly followed it with an eight-track double EP titled Bass Magnetic. Bass heavy, futuristic, and relentlessly funky, Aux 88’s sound was harder and tougher than the electro of New York. This was electro expressed in full awareness of the techno zeitgeist.

Over subsequent releases, as their tempos crept up and their production sound grew more refined, Aux 88’s sound was redefined as techno bass, a meeting of techno and Miami Bass. But such persnickety recategorization was an irrelevance in light of their impact. Aux 88’s releases proved so popular that they helped shape Direct Beat as a key and reliable outlet for Detroit electro. It went on to issue further electro classics from Aux 88 and its members, and from others including X-Ile and Di’jital.

Drexciya

At this time, Underground Resistance stood at a turning point. The label’s first 25 releases had mostly come from core members Mike Banks, Jeff Mills, and Robert Hood (the latter having joined in 1991), either solo or in collaboration; but in 1992 Mills and Hood had both left the collective, leaving room for new entrants. In 1993, Scan-7, James Pennington as The Suburban Knight, and Drexciya all made their UR debuts, the latter of which made an extraordinary and unique contribution to electro.

Formed in 1989, such was the secrecy surrounding Drexciya that only years later could we state to any degree of certainty that the group consisted of James Stinson and Gerald Donald. Abstaining from regular press and promotion duties, they obscured their identities and preferred a slow release of myth-information (issued via artwork, song titles, and run out groove etchings) to describe the oceanic worlds their music inhabited. Fascinating though their mythology is, in the context of tracing the lineage and influence of electro, it is worth mentioning only because of how it informed Drexciya’s sound (but it can easily be researched elsewhere).

Drexciya surfaced in 1992 with the four-track Deep Sea Dweller EP. Unlike the music of their many peers in Detroit, these compositions, like Kraftwerk’s, were made in isolation.

Across a stream of EP and album releases, they proved themselves to be ignorant of the formats and cliches expected of dance music releases, such as intros, outros, and regular bar structures. Their focus instead lay on imaginative melody and the regimented 808 rhythms of electro.

Similarly, in contrast to the sonic ambitions of other dance musics, Drexciya omitted any audio element that was alien to their self-constructed world. The orchestra-mimicking synths of Planet Rock or Detroit techno were banished, as were “earthly” percussion sounds like congas, tom-toms or cowbells. Instead, they supplanted sounds that summoned up images of their oceanic world; rippling currents, plunges into the deep, the searching waves of sonar.

Alongside Aux 88, Drexciya cemented electro as part of Detroit’s techno sound. Unlike Juan Atkins, who ventured into electro, Drexciya operated almost exclusively within the genre. Electro became almost as potent a force within the city’s sound as its 4/4 counterpart.

Underground Resistance affirmed their allegiance with 1995’s Electronic Warfare, which contained not only the electro title track but also the enduring electro anthem “The Illuminator.” New Detroit electro groups like Le Car, Ultradyne, and Aquanauts appeared; Drexciya’s Elektroids alias and Gerald Donald’s side project Dopplereffekt were particularly notable.

Sons of Drexciya: Detroit Inspires Electro’s Next Generation

To European listeners, in particular, the world of science fiction-referencing Detroit techno had already appeared quite enigmatic. But when Drexciya upped the ante to such an involved and mysterious extent, fans were absolutely captivated.

“The early ’90s was a very special time, after the reunification of Germany, to discover all that stuff from America,” remembers Robert Witschakowski, who records as The Exaltics and co-founded electro label Solar One Music in Jena, formerly part of East Germany (GDR). “I was addicted to Drexciya, UR, and with every new release, I felt I went deeper and deeper. It was so influential that we started to make music of our own.”

“Elektroids’ Elektroworld LP. That was the one for me,” says Carl Finlow, who’d already started his production career making house and techno on Warp and 20:20 Vision by the time he was first introduced to the Drexciya side project by friend Daz Quayle. “I’d heard a lot of other stuff like Underground Resistance, but when I heard that, I thought, I have to do this. It just ticked so many boxes; it was sci-fi, it was synthetic, futuristic, it was retro in a way. It was just so pure. It was exactly what I was looking for at that time.”

Inspired by Drexciya, Finlow changed tack from the broad styles of his Random Factor alias to produce his first full album of electro using the Voice Stealer name. Progressing further in his electro explorations, he then assumed the Silicon Scally moniker for a darker, dancefloor-orientated approach. Finlow and Witschakowski were just two of today’s key electro protagonists inspired at this time.

“When I was 15 a friend who was a bit older went to college and was introduced to Drexciya, Aphex Twin, Anthony Rother, Underground Resistance, Silicon Scally,” explains 35-year-old Phil Bolland, who had this music fed back to him via tape. Bolland has recorded as Sync 24 since 2003, has run the electro label Cultivated Electronics since 2007, and also London’s dedicated electro night Scand for 15 years. “For me, that late ‘90s is the golden era.”

“At the end of the ‘80s/early ’90s, the whole Detroit electro sound emerged with Aux 88, Underground Resistance, Drexciya, and Model 500,” recalls Keith Tenniswood. “That was probably my favorite era. Those records still sound amazing now. But directly following that, in the mid to late ’90s/early ’00s, the sound expanded again, lots of it from Europe, with the likes of The Octagon Man, Dynamix II, Anthony Rother, Simulant, The Advent, Dave Clarke to name just a few. There were also countless labels like Clone, Scopex, Touchin Bass, Electron Industries, and Kombination Research.”

Tenniswood’s recollections are, as he says, the mention of a mere few. Detroit’s techno-era electro had proved to be as inspirational to newer electro communities as “Planet Rock” had been to the original era. Countless new contributors emerged. This large number of new entrants prompted mutterings in some sections of the Eurocentric media: “Electro revival!”. But, again, it was a blinkered proclamation. Electro itself had been alive throughout the ’80s and ‘90s. And its influence had been even stronger.

At the same time that Drexciya had been emerging, the original ’80s electro sound was helping to create a ground shift in UK electronica. Electro’s influence was so profound upon this new music that it could be considered equivalent to that which it previously had on hip-hop; electro would shape this sound and it would again spread around the world.

UK Electro Innovation

In the late ‘80s, when raving had been birthed in the UK, Detroit techno, Chicago house, and New York garage were embraced simultaneously. This wide mix of electronic sounds could also be heard on the subsequent free party scene. But when the free party scene was shattered by legislation, clubs once again became rave’s domain. When that happened, things began to change. It became less likely that you’d still hear techno, garage, and house on the same dancefloor. Club nights became more specialized. The scene began to fracture.

In Europe, strikingly so in the UK, the embrace of American music had always held caveats. UK music makers weren’t willing to just slavishly reproduce American music; they were always intent on fucking around with it. Emerging new European subgenres, such as breakbeat hardcore and proto-jungle in the UK, established their own distinct movements within the wider rave revolution.

In 1990, Sheffield’s Warp Records were just one of the new European labels who’d decided they had something to add to the rave soundtrack. They initially did so with a slew of local artists who offered a bass heavy, sometimes bleepy take on techno. But in 1992 they released something quite different.

It’s sometimes difficult to pinpoint the start of a new genre, as musics tend to bleed into one another in the same way as decades do. But in the Warp compilation Artificial Intelligence, which introduced the likes of Autechre, The Black Dog, and Aphex Twin, we can unequivocally state that this was the birth of something significant and new. Techno unrestricted by temper, tempo, or rhythm. Dance music that wasn’t necessarily for dancing.

In North America, some went on to label it as IDM. In the UK it was initially dubbed ambient techno. What’s more relevant is that clearly, somewhere within this new music, lay the unmistakable influence of electro.

“The British incorporated it alongside a whole load of other stuff they were appreciating at the time, whether that be rave, hardcore, hip-hop, ambient,” says DJ Rob Hall, one of Manchester’s Skam Records collective, who from 1990 issued records by Boards Of Canada, Team Doyobi, and members of Autechre. “It all got subtly integrated. The machines were capable of so much more and so there was an interest in noodling around and playing with the format.”

Trying to classify this (or indeed any) music is a pointless pursuit, but in their skippy, broken rhythms, occasional ‘on the one,’ and heavy reliance on the Roland TR-808, the parentage of electro was clearly audible within the music of early Aphex Twin and Autechre.

Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works 85-92 (1992) was riddled with the electro sound, sometimes hardly discernible from a breakbeat as he’d radically slowed the tempo and added unfamiliar backdrops (as with “Ageispolis”). But in cuts like “Ptolemy,” it was instantly recognizable. He would later underline his appreciation of the genre with the release of music by electro acts like Drexciya, Arpanet, DMX Krew, Dopplereffekt, Bochum Welt, and Dynamix II on his Rephlex label.

Others such as The Black Dog, Plaid, Boards Of Canada, Mike Paradinas, Mark Pritchard and Tom Middleton, Luke Vibert, The Future Sound Of London, and Gescom also clearly displayed electro (and hip-hop) influences within this new sound.

“Warp and Skam could only release so much,” says CPU’s Chris Smith reaffirming the link between IDM and electro. Like Warp Records, Smith set up the Central Processing Unit label in Sheffield and since 2012, they have delivered a highly consistent stream of electro from artists like Carbo Flex, Microlith, Sync 24, DMX Krew, B12, and Cygnus. “That was my reason for starting the label. But the first few demos I got were heavily electro. After that, it just sort of snowballed.”

Electro What?

Electro continued to help shape the European response to house and techno throughout the ‘90s. In 1995, Dutch producer I-F released debut his EP, Portrait Of A Dead Girl, on his own Viewlexx label. In doing so, he presented an electro sound distinctly different to that of Drexciya. Compatriot label Clone had been around since 1992, but in 1996 they too debuted an electro sound. In that same year, DJ Hell founded his International DeeJay Gigolo Records in Germany, on which the likes of Jeff Mills, Anthony Shakir, Der Zyklus, and Dopplereffekt were released. Clone issued Drexciyan music, too, and went on to become a reliable source for house, electro, and techno. Fresh ideas were brought to electro from such European contributors, although the late ‘90s electroclash genre which they precipitated spiraled far from the original sound and identity of electro music.

Similarly, the subsequent electro house genre bore few elements from actual electro. But it’s notable that electro had continued to be an inspiration to other musics, even if in name only, well into the 2000s.

A New Home And A Fresh Audience

More exciting and directly identifiable is how electro has since filtered into British urban musics. Electro has found new genres to collide with in dubstep and UK bass music. Their audiences are way too young to have heard “Planet Rock” when it debuted, but the feel of the music is instantly recognizable to them because of its perpetual existence within (and influence on) today’s dancefloor palette. The similarity in mood and tempo between electro and some modern British urban musics is something that has been noticed across many a young dancefloor. Electro divides the opinions of post-dubstep dancers a lot less than it did those on techno dancefloors in the 90s.

“I find it easier to dance to electro,” says Hamburg based DJ Helena Hauff. Namechecked by almost everyone interviewed as being a talented and positive force within contemporary electro, Hauff has experienced a huge rise in bookings and audience numbers over recent years. “With four to the floor, it’s not necessarily so easy or immediate. I guess it depends where you come from because when I play in England or Scotland I feel like it’s going down way better than it does in Germany. It might be because they grew up with a lot of breakbeats, drum n’ bass, and dubstep?”

That electro is so easily recognized and adopted by young clubbers should surprise no-one. Nor should electro being such comfortable bedfellows with cutting-edge urban British electronica.

“It just has a timeless quality,” states Neil Landstrumm. “It keeps being referenced in popular culture, it just keeps recirculating. I think it’s maybe because of the darkness in it. It’s not particularly euphoric, it’s sparse, steely, metallic, and I think that helps keep it current and fresh.”

What does surprise is that there should ever be the need to proclaim a revival of electro. To do so displays a lack of perspective. This is a music, after all, that predates house and techno. It is a music that has arguably had more of an impact on fashion and dance than either. As a building block of the evergreen IDM movement, it is certainly no less than equal to house and techno. And its impact on the goliath of hip-hop has been profound, whereas their’s have been largely insignificant. Electro is a music of perennial endurance and persistent influence. It deserves to be recognized as such. Central to this understanding is perception, and also an acknowledgment of just how fundamental and ever-present electro has been.

“I don’t think there is a golden era for electro music,” says Helena Hauff, echoing thoughts expressed by others interviewed here. “I don’t think it’s ever gone, it’s always been there.”