Francis Harris: Cleared of Concept

Francis Harris has been making emotionally charged atmospheric soundscapes for the best part of six […]

Francis Harris: Cleared of Concept

Francis Harris has been making emotionally charged atmospheric soundscapes for the best part of six […]

Francis Harris has been making emotionally charged atmospheric soundscapes for the best part of six years. Within this period, he’s released two exceptional solo long-players—2012’s Leland and 2014’s Minutes of Sleep (both of which were required a repress due to high demand)—and one 12”, Minor Forms, plus some collaborative material. On October 19, Harris will return with Trivial Occupations, a third LP under his own name, and one that sees him embark on an “altogether more personal journey” than all his work before. Recorded over a four-year spell in Brooklyn, New York, Harris describes the process as both “challenging” and “liberating.”

Harris’ music has not always been so richly-textured and personal. Up until 2012, almost all of his solo work had come in the form of loopy tech house, released as Adultnapper via the likes of Ransom Note Footnote, Superfreq Records, and Poker Flat Recordings, the latter of which was the intended home for 2012’s Leland—before label head Steve Bug declined it because it’s easy-listening vibe was not a good fit for his dancefloor-focused label. Encouraged by friends Anthony Collins and Shawn Schwartz, Harris opted to set up his own Scissor & Thread label as a platform for the album. “I really didn’t think anybody would want to listen to it,” Harris recalls. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to share it because it felt so deeply personal to me.”

It was certainly a drastic change of course. Long gone were the thick, driving basslines and electronic sounds, replaced with nuanced electronica rich with organic textures, blissful vocals, and jazz references. The spark was the death of his father, a loss that “transformed it [the album] into this requiem,” Harris recalled in a previous interview. “Instead of using my computer, I used a lot of hardware. Once I started focusing myself in this direction it didn’t feel natural to go back to Adultnapper.” It’s a deeply emotional piece that captures the sentiment that such a trauma can bring.

2014’s Minutes of Sleep was similar aesthetically and also deep-rooted in family tragedy. Having suffered for many years, Harris’ mother succumbed to cancer soon after his father, and the emotions bled into the album. Though honest and again deeply personal, it also feels more guarded; less heart-on-your-sleeve and more mature. “It’s [the album] less of a straight requiem and more of a representation of how difficult it was for me to operate in that tension,” Harris said to Resident Advisor in 2014.

Fast forward four years and Harris finds himself in a different headspace. After suffering from depression and having gone through something of an “existential crisis,” he’s found comfort in meditation and running, allowing him to feel “much less heavy.” It’s in this headspace that he’s recorded Trivial Occupations, a four-year project with no clear concept or framework. “This led to all sorts of existential rabbit holes. So I decided to go back to the beginning, which was no beginning at all,” he explains in the press release. “It’s just an artist album, and I think it’s the first time I’ve made an artist album for no other reason than just making it.” To learn more about his artistic transition and the processes behind Trivial Occupations, XLR8R dialed in Harris one afternoon from his Brooklyn studio.

The last time you spoke to the press at any length was in 2014, and you were going through a significant period of personal change. What’s happened since then?

I realized that I went through an existential crisis after that period. You have these two albums that are sort of iconic given their conceptual backgrounds; they’re tied to personal history and people are drawn to histories, especially with artists, for whatever reason. Leland, the first album, is bittersweet, and Minutes of Sleep is firmly based in an obvious melancholy because it was addressing themes of grief and how this can be integrated into one’s artwork. When I started working on this new record, Trivial Occupations, I was deeply involved in the Frank & Tony project, making deep house records, and I was also working with Gabe Hedrick as Aris Kindt. I was a little bit lost in what I wanted to do musically speaking, and I became depressed; writing those last albums helped to keep my mind off the adversities from the deaths of my parents, and so I think the depression was delayed. As part of my recovery, I started to run—I did my first marathon last year—and in the running, I began listening to Buddhist meditation books and the archived lectures of Alan Watts which sparked a real interest in mindfulness and meditation.

How did this influence Trivial Occupations, your third album released under your own name?

One of the big revelations from mindfulness training is this idea of letting go of concepts and history, and, in a way, learning to live in the moment, however cheesy that may sound. That’s where the title of the album comes from: it’s about not taking yourself seriously or the concept seriously, or musicianship, or any aspect of codified music culture. In a way, these can trap you into categorical thinking. So I just started writing music again in the same way as when I was writing guitar music in my 20s. I had a four-track recorder and just began experimenting with ideas. I was recording stuff on the piano. I had about 20 or 30 basic ideas or themes, many of which grew out of relationships with musicians in New York. We were sending each other bits, and that’s why it took so long to complete; I didn’t really want to put a timeline on it. At a certain point, the record felt finished. I was just kicking the music around in my studio for four years until it became the songs that are on the album. It was a purist approach.

Yes, the main talking point is that it’s your first album under your own name made without a concept, following Leland, which was about the death of your father, and 2014’s Minutes of Sleep, which captured the grieving period after losing your mother. How did you handle writing an album without a clear concept?

I think it was challenging and then liberating. I certainly went through a period where I was really stressed out because there was no concept; at times I thought, “Maybe I should just never release another solo record.” Maybe Minutes Of Sleep is it. Then I thought that was just a cop-out because I love making music on my own. Collaboration, as good as it is, has its limits, and at some point, it began to feel good just writing music for myself. With most things in my life, I drew inspiration from literature and movies, like “Song For Aguirre,” an imagined soundtrack to “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” by Werner Herzog. And then when it started to come together, it felt kind of liberating because there were no preconceptions. It’s a truthful album. I wasn’t trying to imitate or accomplish anything grandiose or super challenging. It’s just an artist album, and I think it’s the first time I’ve made an artist album for no other reason than just making it.

How do you feel this impacted the aesthetics of the album, if at all?

Perhaps there is a looseness and ease to it that was not apparent in the last two albums. I think I also experimented a lot with this one in terms of production techniques and the way it was mixed.

Minutes of Sleep is a stirring and complex record threaded with the uncertainty of losing your mother. What sort of emotions do you think are conveyed on Trivial Occupations?

Dare I say a little hope? When you meditate on the impermanence of everything including your own existence, everything becomes a bit lighter.

Do you feel the emotions of your traumas still bleeding into your music?

The nature of the grief is that it never really leaves you. It’s like putting a rock in your pocket: you can go out and be having a really good time and then you reach in your pocket and you think, oh that’s there. So I think my music will always be somewhat melancholic. Even before this as an emo punk kinda guy, my music has always drawn to melancholy. I am not really into happy music. Certainly, there are still remnants of this emotion in Trivial Occupations, but I just wasn’t focused on it.

What do you think draws you to this melancholy? What’s its appeal?

I wouldn’t exactly call it an appeal, but I suppose we are all drawn innately to certain styles or sounds. I think people who live a more inner life tend to frame existence in somewhat of a melancholic way, perhaps to a fault. This is not to say that we are depressive. Melancholy is directly tied to the nature of existence, that being the inevitable passing of time.

Do you find making music to be a cathartic process?

I try not to use cathartic when describing any process as it implies some level of meaning or importance to one’s work. I would say it’s more like a sigh of relief. That said, music is really the reason why I get up in the morning. It’s my only solace. At the same time, it can certainly be torturous. I can tell you this: each one of these album songs was on the verge of being in the trash at some point because self-loathing is part of any process. As my life-partner can attest to, I’ll sometimes wake up in the middle of the night feeling that I’m worthless as an artist, questioning why I am even doing this. I have trouble connecting with people who are confident as artists because I’ve never felt confident about anything I’ve done artistically. My approach to the arts is always about asking relevant questions. Art doesn’t provide any answers but it helps to frame questions of life in a way that sparks curiosity and continued desire to create.

Did you find your work as Adultnapper to be similarly relieving?

I’m not sure I had any real ideas as Adultnapper. I was too busy trying to prove something to myself that didn’t really exist. This idea that what I made really mattered or, better yet, what I was making light of in parodying critical theory mattered beyond my own self-gratitude seems in retrospect to be very petty.

Speaking generally, the album feels more ambient, with some entirely beatless tracks. Was it your intention to distance yourself further from the dancefloor?

Not at all. To me, the record is still for the dancefloor, but it’s just a different kind of dancefloor. “Dalloway,” the song with Kaïssa, is African dancehall. I have been buying lots of this stuff on vinyl and I just started writing beats one day. The track just became this sort of vibe, and I began reaching out to vocalists to see if they’d want to work with this boring guy in Brooklyn. So I think you can still feel the dancefloor in the record. One of the things about club culture that annoys me the most is this constant need for a dancefloor to be going “off” and the energy to be high. I don’t know why there is this obsession with the dancefloor “blowing up.” I hate that term. For me, I want just a grooving connection between the dancers and the artist, and you can do this with or without beats. I love house music, of course, but what I love about it is that it’s based on community and connection rather than disconnection. It’s not about ego and hands in the air. The perception of what dance music is just far too narrow.

It begs the question: what is a party? Why do they have to be druggy, late night, non-responsibility affairs that promote disconnection?

I think a lot of people, myself included, are living with a lot of pain and want a way to escape, but as I learned through my own experience, pleasure is not the answer to pain.

Given that there was no real framework around the music, how did the tracks begin?

While writing the album, I was taking piano lessons. It’s the first time I’ve taken music lessons in my life; I’ve taught myself guitar and all the other instruments I play. Each song is based on a theme that I crafted on the piano then recorded on a four-track. I then recorded other ideas and layered them with collected field recordings—all the sound beds have these various layers. Funnily, in most cases, the original theme is not actually included in the final track. The piano on the three songs where the instrument is highlighted is played by Leah Lazonick, as she is a much better pianist than I, but it all started with these simple themes which then expanded into something much larger. I just let the theme run its course with no expectation. It was a totally different approach because the core music is all me.

What exactly do you mean by a “theme?”

I mean an actual musical theme. Like a four-bar loop on the piano. For example, in “Song For Aguirre” it’s just the baseline. I started the songs with basic musical themes and expanded on them, and they became something entirely different from what I started out with. It’s a simplistic way of approaching it. I can go into the project folder for each one of the songs and see this basic first theme. I actually shared the progress of a few of these songs with Terre [Thaemlitz, DJ Sprinkles] and she recently told me that she had gone back and played several versions of the same song in her DJ sets. It shows how much each song evolved in the process.

Why do you think the tracks changed so much?

I think it’s just a reflection of my state of mind. I could have just left the tracks in their original shapes, where they were at the beginning, but they became something else. I can’t really explain why I made those choices, it’s just an instinctual thing, when you know it needs to go in a particular direction.

Given the absence of a concept, how did you ensure the release is cohesive rather than just 10 tracks? Did you spend a long time mulling over the tracklisting?

It’s an interesting question. The album was done in many different periods with many different people so it felt like pieces of a puzzle that doesn’t exist. Each track is just a snapshot of my life and my states of mind over a four-year period, and once I put them all together it didn’t feel cohesive. Recording Leah on the piano was important; I felt that this added some cohesiveness compositionally on a few of the songs. She played a vital role in actually feeling like the record was finished. I also felt like there was no ending, so the final track, “No Useless Leniency,” was actually written to close out the release, as a period to the end of the sentence. But in a way, the album still feels more like a various artist compilation, and that goes back to the title, Trivial Occupations, because there really isn’t a meaning to it.

I want to zoom out a little and discuss the transition to this more contemplative music you’ve been making after Adultnapper. Trivial Occupations, of course, is a continuation of this new musical direction. Why did losing your father inspire you to make these changes?

I don’t think there is really any consciousness involved in making these decisions. When you go through these sorts of traumas, like losing both your parents in the span of a few years, you realize that none of this bullshit matters. The only thing that really matters is being at peace with your own existence, and having people around you that you love and care about while having respect for your environment and those around you. I felt that being involved in a culture of abandonment that really is not about anything but losing yourself and not taking responsibility for that process didn’t really ring true with me anymore. I think today to be part of a counter-cultural movement, one has to embrace responsibility rather than the opposite. When you lose someone close to you, the importance of family and community becomes much more present. Every action matters. As long as I can take responsibility for how my actions affect others, I feel that I can begin to be more at peace in my own life which, in turn, erases this desire to fill an empty space with a metaphysics, whether that be in drugs in alcohol or even religion.

Does this music feel like a more honest artistic expression than your music as Adultnapper?

Absolutely. I feel like the Adultnapper was not very genuine. It was utilitarian dancefloor stuff, which is cool but I just can’t connect with that side of my personality anymore. I don’t like being the center of attention, I don’t like people looking at me, I don’t like dancefloors where people are all looking at the DJ. I don’t like a hierarchical artistic approach. For me, the purpose of any pursuit of the arts is to lose the self rather than to build up a false self. That being said, Adultnapper was sort of a joke anyway; the name was a piss-take on post-structuralist French philosophy and the jargon behind it. But even that was a display of my own intellectual insecurities. As I’ve grown older, I’ve realized what a joke all of that is. The only thing that matters is the work and it’s my priority to have the work be as truthful as it can be in the moment that I am making it.

So do you care about how your music is received? Do you read reviews?

I try not to. I used to really care. But I think the more experience you have making music, the less you get wrapped up in the trappings of reception. The work is all that matters.

Looking back, did you perceive Leland as an experiment? Did you perceive it to be a risk?

I really didn’t think anybody would want to listen to it. I was lucky because Shawn Schwartz, who started Scissor & Thread with me before I even met Anthony, championed me, and I’m thankful that he convinced me to put this music out there. I wasn’t sure I wanted to share it because it felt so deeply personal to me, and at the time I was touring a lot as Adultnapper. I’m grateful to him as a friend that he convinced me that it was worthwhile to share. I would have never have guessed that I’d end up repressing the record and the one after. As I said, I have no connection with artists who expect attention; I just assume that nobody is going to pay attention to anything that I do. I am deeply suspicious of anyone who is overly confident in their art.

In terms of production, Minutes Of Sleep was wholly written using microphones and samples, recordings that you then sequenced, and drum machines. Was it the same techniques on Trivial Occupations?

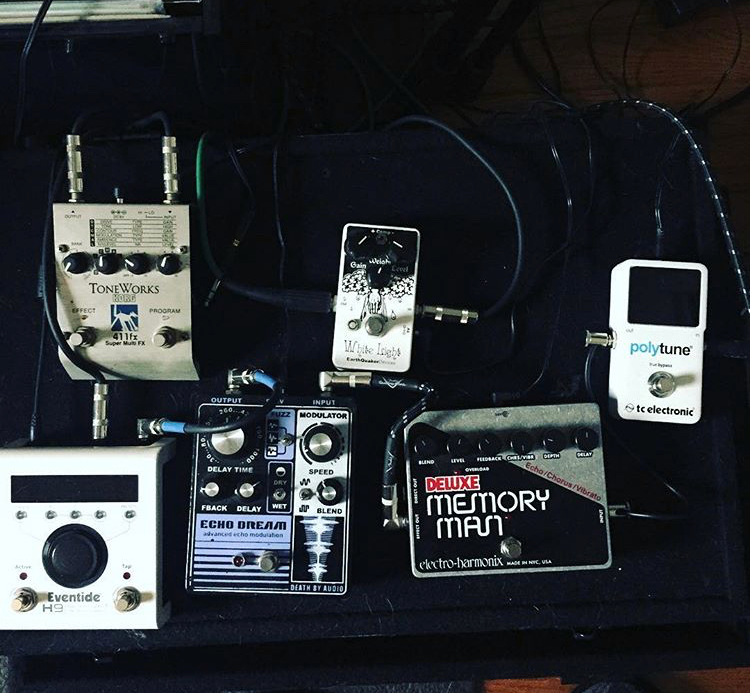

It’s a little different. There are a great deal of recordings, obviously. With Minutes Of Sleep and Leland, the sound revolves around the work of Emil Abramyan and Greg Paulus, and I feel that this record is different because of the indelible mark left by Dave Harrington. My friendship with Dave is the biggest revelation on this album. He’s probably my favorite person in the music business right now. He’s just this insanely talented multi-instrumentalist genius with zero ego. Making music is just like breathing for him. I also limited my production techniques on this album. Every synth sound is done on one synth. It’s a synth I am obsessed with, the Yamaha TG33, a cheap Japanese wavetable synth from the ‘80s. It, along with and I about 20 different guitar pedals and effects, shaped a big part of the central sound. I also used quite a few microphone samples, too, and all the drums are done on an MFB Tanzbar.

Besides Dave Harrington, the album also features appearances from Kaïssa and Genevieve Marentette (vocals), Leah Lazonick (piano), Will Shore (vibraphone, Greg Paulus (horns), Emil Abramyan (strings), and Robb Reddy (sax). How did you connect with these artists?

If you knew how many emails I sent to get a vocalist for “Dalloway” then I think you’d be amazed. I must have contacted 20 or 30 vocalists and never heard anything back. I got lucky because Kaïssa lives in New York and is a singer from Cameroon. I spent a lot of time listening to vocalists until I found someone who I felt would work on the song. The rest of them are just contacts. New York is full of brilliant musicians.

It’s interesting that you worked with Will Shore.

Yeah, he’s a young guy in his early 20s. He’s such a well-developed artist already, and I think it brings a freshness to the album. You can really feel his energy when he comes into the songs. There’s this youthful positivity which I feel elevated the album to feel a lot more positive than my other material. He’s a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed positive musician. You can really feel that; it’s a nice contrast to my propensity for melancholy.

Which tracks do you think capture this the most?

“St. Catherine and the Calm” is all about Will’s Vibes.

Who is the vocalist in “Trivial Occupations?”

Genevieve Marentette, a jazz singer from Toronto. She’s also one of the organizers of the Toronto jazz festival. I was trying to find a new vocalist because I wanted to close the chapter of working with Gry [Bagøien]. She’s incredible but we had done everything that we wanted to do together. I reached out to Genevieve, and it’s great because she’s so specific. We talked about the lyrics and the direction of the song for months before she laid anything down. Even after she laid something down, she went back again and then there was a lot of back and forth during the mixing. She really captured the spirit of the album with the vocals. It feels very ‘70s Alice Coltrane sort of style, which is what I was going for with that piece of music. It’s one of the most challenging compositions I’ve worked on, and a new step in an entirely fresh direction.

What do you perceive to be the importance of analog sounds in this new music that you’re making?

I am just a man who requires a process. I actually admire people who can sit down with soft synths and make cool music. I can never pull that off. I need something to mess around with; I find great pleasure in all the happy accidents that come from working with gear. It’s just a lot more fun for me.

Is it also important for the textures?

It is. I am a huge fan of microphones and this is one of the reasons I like playing vinyl: I like the little microphone. I like the idea of microphones capturing the atmosphere of any room that you’re in, as it becomes an archive of your life. There is a wonderful sense of vibrancy in any recording with all the imperfections. I embrace these mistakes, and if they feel good, I will just leave them in. Microphones are a reflection of the imperfection of our own existence.

You said earlier that music is the reason you wake up in the morning. What is it that drives you, after so long doing it?

I think it’s somewhat intangible, but when you enjoy working on something, it becomes much like meditation. You forget to think about thinking. Also, my love of music is about curiosity and always feeling like an idiot, like I don’t know enough. I listen to the LOT radio every day and it’s unbelievable the sorts of records that are out there. How can you be involved in music and not be curious? How can you not want to push limits and take risks? It’s not about being patted on the back and being rewarded for taking risks; it comes from inside, and a passion for new sounds.

What role has meditation played in your recovery from these earlier traumas?

I don’t feel heavy anymore. I don’t take myself seriously either. It takes a lot of work to take yourself seriously and to worry about what people think. If you just stay in the moment and mindful of the people around you, then it can be very liberating, as its no longer about you and the little problems that fill your day. It’s simply just another moment that is always passing. The best we can do is try to feel the energy of it before it’s gone.

Do you think carefully about where you’re going artistically?

I think that’s a trap. I try to avoid this thought at all costs.

Trivial Occupations LP will land on October 19 via Scissor and Thread.