Get Familiar: Forbidden Planet

A Montreal party-turned-label explores both the dreamlike and nightmarish ends of the dancefloor.

Get Familiar: Forbidden Planet

A Montreal party-turned-label explores both the dreamlike and nightmarish ends of the dancefloor.

Dance music and science fiction get along famously. From the beginning, techno artists and labels have traded heavily on a lexicon of imagined people, places, and objects—giving club music more than its fair share of dystopian clairvoyants like Jeff Mills, Drexciya, and other pioneering Detroit futurists. The Forbidden Planet label, a recent arrival on the techno scene, references the past as well as the future. It takes its name from a 1956 film starring Walter Pidgeon and Leslie Nielsen, which is essentially a Freudian retelling of Shakespeare’s The Tempest set in outer space. Forbidden Planet envisions a world that is both dreamlike and nightmarish—qualities complemented by Bebe and Louis Barron’s alien soundtrack of singing circuits.

Jurg Haller‘s Montreal label also reflects these dual states in its music and artwork, though, as he points out, it takes virtually nothing else from either the Barrons’ music or the movie itself. “I didn’t want to recreate the subject matter of the film in musical format,” says Haller. “I was mulling over different names for the label, and I wasn’t satisfied with anything. Forbidden Planet was one of the first electronic productions I was listening to really deeply, and I just thought, What the hell, I’ll just call it that.”

Breaker 1 2, an alias of Greg Beato, gave Forbidden Planet its highest-selling record to date in 2013, just a few months after the label began. “2” is a bare-bones 909 workout, with double- and triple-time clicks that sound like fluttering insect wings and an unbroken loop of organ notes. It’s a beautiful record housed in an unsettling sleeve: a humanoid figure on a stool with a blurred face (which the insert reveals more clearly as a skinless man with a brimmed hat and a maw for a mouth).

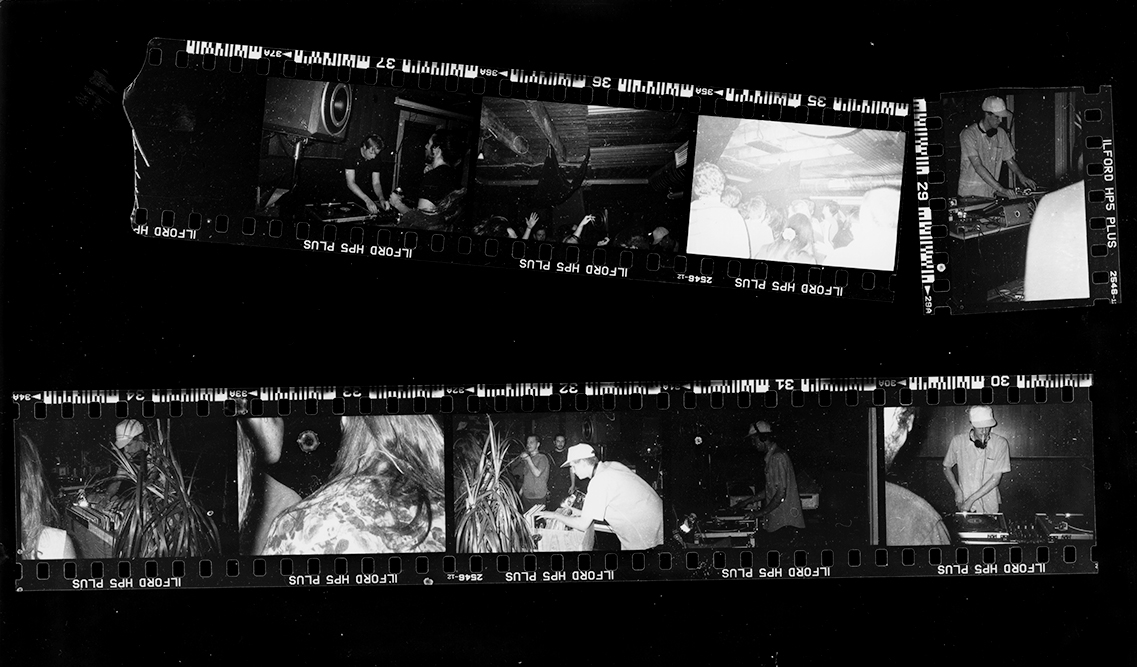

Paul Gondry, who does all of the label’s artwork, varies the sleeves according to the mood of each release. For instance, the artwork on Dan White‘s untitled 2014 EP features men on motorcycles riding through a landscape of chalky blues and greys, reflecting the slightly brighter tones of the music (particularly “Death Flutes,” which may be the jauntiest track released on Forbidden Planet). In some ways, Gondry’s sketches resemble storyboards for graphic novels, which perhaps isn’t too far-fetched. “It’s not a concept we talked about,” responds Haller, “although we had thought about it, of having almost like one long story between each cover. Paul makes lots of movies, he makes comic books… He produces constantly, and he’s really interested in comic books, which is something we bonded over initially as well.”

Forbidden Planet began in 2011, first as a party in Montreal under another name. Haller—who had moved from Boston to study art history, cinema, and economics at McGill University—was introduced to the “tight-knit” scene in Montreal by Bowly, a well-connected grime DJ. He showed Haller the ropes, helping him meet the right people to make the party happen. Alongside co-resident Paul Trafford, Haller would often start the night with “some experimental music, some noise,” before “slamming together” balearic, Jah Wobble, and M. Zalla records alongside the dark, ravey house and techno that informs the label. D’Marc Cantu was the first DJ that Haller hosted. Buoyed by the success of their party (which was billed as “Booma & ESL present D’Marc Cantu,” after the DJ collective Haller had recently joined and Bowly’s own crew respectively), he quickly asked Cantu to send him tracks. Soon after, Forbidden Planet issued its first release, D’Marc Cantu’s four-track 12″ Some Fantasies Are Good.

Now living in New York and running a gallery full time in the city, Haller threw Montreal’s last Forbidden Planet party in January 2014. The label has since released a series of stellar records by Boreal and Lnrdcroy (the latter’s fragile breakbeat seance, “Do.ne (Original Altitude Mix),” being the pick of their three offerings); Finnish techno producer Mono Junk, whose “With You” features synths that bubble and chime underneath a parched vocal; the aforementioned Dan White record; the clinical, Armando-ish acid house of Annanan’s Lyser EP; and, most recently, a reissue of The Mover‘s tracks released in the early ’90s by Planet Core Productions.

These records—and the label as a whole—are superficially distinctive for their adherence to what we think of as “science fiction”: the tangential comic book references, the dystopian vibe, and their techno-centric interests. But in truth, sci-fi is only a small part of Haller’s array of aesthetic allusions. When asked to what extent the worlds of music and art he occupies collide in practice, he says, “My artistic tastes run from the Danube school to sculptures by Renaud Jerez and the Swiss pop artist Friedrich Kuhn. Similarly, I’m also interested in acts like Sophie or Kool Keith, but also Yukihiro Takahashi and B12.”

Haller later says he “abhors orthodoxy,” and considers these disparate artists and interests to be part of the same world. This unlikely convergence would have a hard time impressing itself on a Forbidden Planet release as things stand—the label seems to be a decidedly specific world—but Haller’s polymathic tendencies have served his endeavor pretty well so far. Though, as Haller suggests, it hasn’t been the fruit of some grand plan. In the same way he asked Cantu to email him music as they took a cab to the airport, many of the decisions he’s made since have been more about intuition than design.

“I’ve just released music I thought that was really good, and I believed in,” he says. “It’s also obviously a reflection of my own personal tastes and aesthetic sensibilities, but I never had this grand plan about it being futuristic or anything like that. It’s interesting to look back at all the releases, because I’m not really so aware of it. But when I talk to my friends, and they talk about the sound of the label and the artwork, it does kind of really comes together. But that was never so much my intention as much a reflection of my sensibilities.”