Get Familiar: Un rêve

Light conversation with one of Mexico's best kept secrets.

Get Familiar: Un rêve

Light conversation with one of Mexico's best kept secrets.

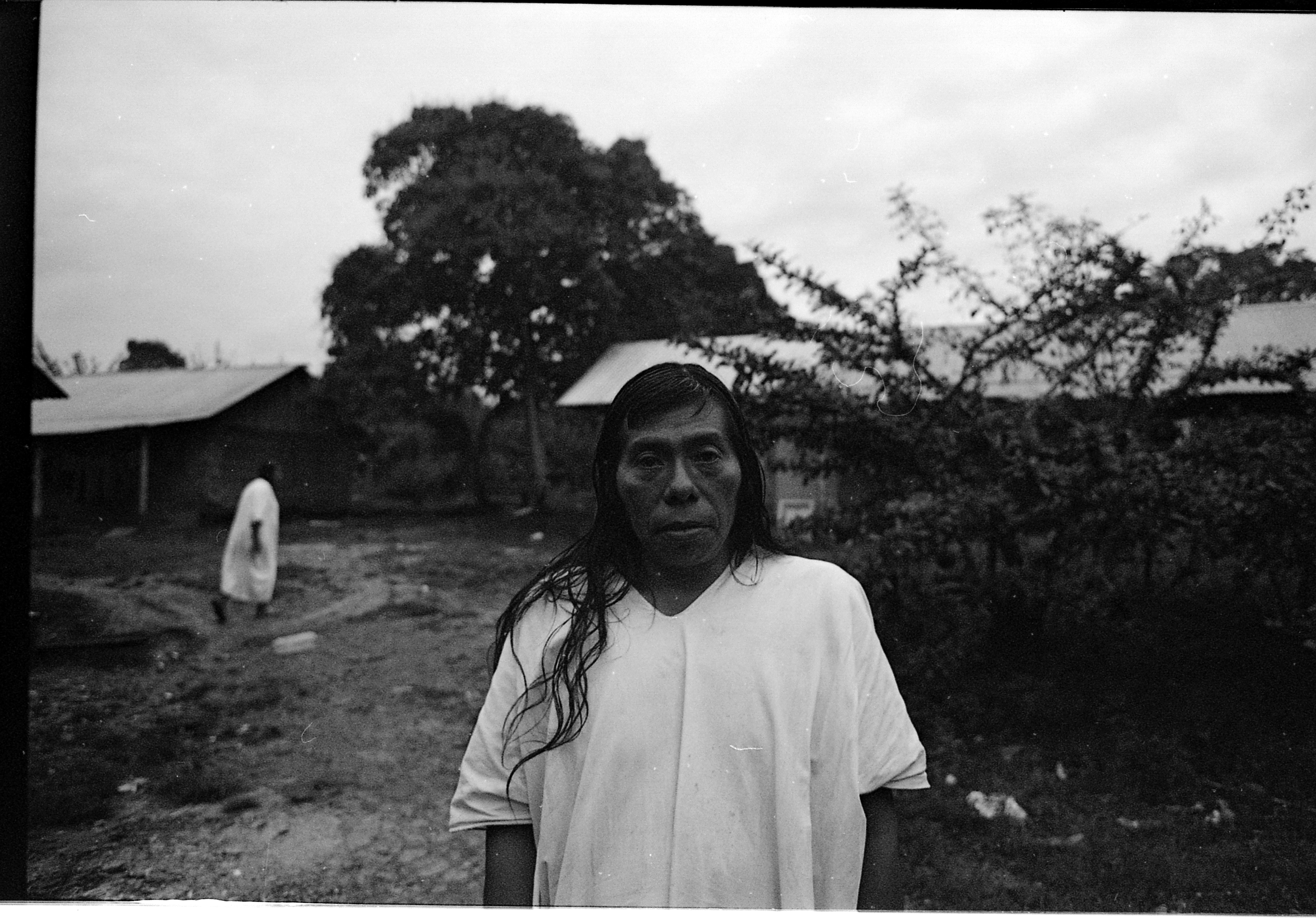

Un rêve is an experimental musician from southern Mexico City, real name Diego Cornejo Vázquez (a.k.a Dídac.) He’s 27 years old, and passed the majority of a “very fortunate” childhood in Ajusco, a wooded mountain area located to the south of the nation’s capital, away from the hustle and bustle of city life. He spent lots of his time isolated, absorbed in his own memories and dreams.

Dídac began making music in 2009 with just a few instruments, a computer, an audio editing software, and what he calls “a very innocent notion of musical production.” The alias became a space where he could vent, to escape, and to say the things he wanted to say, but also a way of listening to himself, what he felt, and what he dreamed. “Songs came out as a relief,” he explains. “I compose for myself, as a self-recognition, an emotional blog.” His sound is deeply introspective and emotionally evocative.

For many years, Dídac maintained a somewhat hidden profile, uploading his music to his social networks but without ever promoting himself. “I never thought about live presentations, collaborations, formally recording a record, and much less that the music would take me to where it has today,” he explains. But soon he began receiving messages from those interested in his music, many inviting him to play live, and so he set about recording his first studio album, Por la hierba que besa mi tobillos cansados (meaning “By the grass that kisses my tired ankles”), which launched in 2014. It was followed by a wave of performances across Mexico, fuelling his dream of becoming a full-time recording artist.

Only more recently, Dídac returned with his second album, Como árboles al cielo……encuentro (meaning “Like trees to the sky … I find”), available now across three Mexican labels: VAA, Otono, and Gravy Records. To fund the mastering by Taylor Deupree of 12k, Dídac raised money via Kickstarter, and is still seeking funds to prepare a limited vinyl pressing. As you’d expect, the music is chilling, deeply emotive, and wildly cinematic—a downtempo adventure that aims to inspire self-reflection. To learn more about it, we dialled in Dídac one afternoon from his Mexico home.

You’re a Mexican artist with a French name. What’s the connection with “un rêve,” meaning “a dream”?

When I started recording and sharing music, about 14 years ago, I changed my name several times because I was not really sure what to call the project. However, dreams have always been a source of stories, memories, longings, and sensations that I wanted to express through my music. I did not like the idea of calling myself “Un sueño,” Spanish for “a dream,” maybe because it seemed somewhat pretentious, and at that time I liked the music of múm, and when translating it I liked the French version of “a dream” visually for the simple fact of the French accent (^). Actually it was something that I did not think much about at the time, but it’s gained meaning at time has gone by!

Talk to me about growing up in Mexico. Where did you spend your early years?

I have a lot of love for Mexico, its landscapes, animals, plants, and beings. I had a very fortunate childhood, growing up outside of Mexico City but traveling at every possible occasion to Chiapas, in the south of the country. Chiapas is one of the state’s richest in biodiversity and it is in constant transformation as rivers, trees, animals and habitats continue to disappear under the human footprint. Those days seem to me like rather dreamlike memories of a world that is constantly changing, and I feel that it has almost vanished from my memory now.

Growing up in Mexico is a paradox—a complicated, beautiful, cruel, and sad dualism. There are beautiful cultures, people, places, stories, and foods that fill my life, but there’s also a constant pain—a helplessness and sadness caused by the abuse by a non-existent superiority. There is so much inequality; and there is poverty, hunger, marginalization, racism, and also a lot of violence. Together, we have witnessed the cruelest faces of humanity: massacres of students, and of indigenous people, and to just about anyone who gets in the way. Can you believe that it is estimated that seven women die in Mexico every day? Or that every 17 minutes there is a murder?

How much of the sadness in your music is a reflection of your childhood in Mexico?

Many of my songs reflect memories of my childhood, especially those first ones. It could perhaps be said that these experiences shaped by sound, and from there the essence has remained, like a language of sorts. I like to imagine that my music evokes in the listener this same type of image, the moment in our childhoods in which we are not aware of all the terror that may be surrounding us.

How did you connect with electronic music growing up?

There is really no depth to my connection with electronic music. I began listening to lo-fi, post-rock, and instrumental music, and I also wanted to make music. All I had at my disposal was an electronic keyboard that I found in “las chacharas,” meaning the street market where you buy old or used objects, and the various acoustic instruments such as guitars, melodica, harp, etc. that I had picked up on my way. I released my first album, Por la hierba que besa mi tobillos cansados, with this, and from there I started to meet friends and colleagues who also made music. Living together and collaborating with them has shown me more branches of sounds and genres of electronics.

How did you learn, or was it just a case of trial and error?

Everything has always been like a game, or an experiment. I learned and approached music thanks to the interest in the family: my grandfather was a marimbist; several aunts, uncles, and cousins play instruments or sing. We say here “se trae en la sangre,” meaning “it is brought in the blood.”

The accessibility provided by computers and production software suited me perfectly. At first, I just locked myself in my room trying things, using what were in effect toys for children. I even recorded some songs with a microphone made for video-chat; and I actually think that lo-fi essence has remained, and that this has given a nostalgic identity to my music.

Am I right in understanding that all your recorded music is fully improvised?

All the music before my first album is made from pure improvisations; it was just what flowed out of me at the time. What mattered most to me was to capture the feeling that invaded me, and turn that into music. Little by little, I got closer to the audio editing programs and with the help of friends I began to compose with more complexity.

Improvisation is still very important to me, because it’s a source of relief where without judgment I allow myself to be carried between the frequencies. It’s where melodies appear with which I can identify myself and I catch them to later detail deeply in my studio room.

How do you spend your time outside of music?

The problem is that I spend more time outside of music than I would like. I studied communication but I struggled to find a job that I liked. I was working for a few years with an information agency but I became depressed by the quality and quantity of tasks; it seemed like a lot of “junk” information aimed only at getting more clicks on the page. I’m now currently studying ceramics, and I’ve been working at night as a barista and cooking pastries. That’s my basic routine, but I try to use the few days off to collaborate with several creative people in different disciplines.

What other artistic disciplines do you work with?

I like photography very much—in fact, I started capturing images almost at the same time that I started composing as Un rêve. Memories are a fundamental source of inspiration in my life because they help me to remember who I am and who I seek to be. There is in me the nostalgia of yesterday and photographs serve as small windows that allow me to embrace the feelings and emotions of a particular moment or time just by seeing them. I like to collect children’s photographs and invent stories with them.

Last year, I also started to get involved in ceramics. I went to study at the School of Handicrafts, and even though it is a new world for me it has completely amazed me. I am just getting to know the techniques and processes, but the head starts to fly when I imagine that one day I will be able to unite ceramics and music.

Your music is dark, deeply moving, and highly introspective. What is it that you are trying to provoke?

Introspection—searching oneself for questions and answers—self-recognition, acceptance, and love for oneself. I like to invite people to remember their own stories, bring them to the present, and take shelter among them. We all have our stories of love, of sadness, of anger, of disappointment, of tears and joys; and I like to think that by expressing how I feel through sound, I am inviting others to see themselves reflected in themselves.

What sorts of emotions does that music evoke in you?

For me, it evokes an encounter with myself, listening to me, observing me, accepting and loving me. My music is an extremity of my feelings and emotions. I do not know what I came to do to this world, but at least I have found true love by listening to myself and accepting myself. In my music I listen to all those landscapes, people, animals, and plants that have marked my life; it is a tribute to all those special moments that have come before.

Given the intensely personal nature of your work, how do people respond to it in a live setting?

In many ways, and each one is beautiful. Many people come to tell me that they remembered precise moments of their lives, or that they I reminded them of a loved one or even a pet. In the live presentations I have seen many people absorbed, with their eyes closed and faces reflecting the feelings they are experiencing at that precise moment. I think that in general there seems to be an effect of trance, of contemplation and careful listening. Many people have told me that they feel they have gone to another place. I remember a presentation in Puebla, where at the end a couple came with tears in their eyes to thank me.

Are there many other artists making similar music to you in Mexico, or do you consider yourself quite insulated?

I think that there are several musicians who have a lot in common and I think we are all somewhat isolated. Commercial music really dominates the air today; it is a locomotive that is clear about its objectives and overshadows everything that is below it.

I feel isolated in how to manage my music, in how to get contacts with promoters, or just how to make myself known. The marketing that has to be done if you want to be listened to exhausts me, and it makes me feel a sadness where I sometimes lose the sense of why I make music. I would like to live from the composition, but, at least at this moment in my life, it is very difficult and therefore I must look for other jobs or dedicate myself to other things.

What’s the story behind the album title, Como árboles al cielo… encuentro?

It is a beautiful anecdote. When I was a child, maybe five or six years old, with my family we visited an uncle who lives in the Lacandon jungle of Chiapas. One day, my uncle took us to meet the Chankin community, a group of Lacandones in the foothills of a mountain jungle. When we arrived, I was impressed by how this community could communicate with each other, and from a distance, with such a low tone and volume; they seemed to be sighing when they spoke.

It was the first time I visited this community and for me it was like traveling in time. There was no light, the houses were made of palms and logs, there were children collecting chicken eggs and drying beans in the sun, I saw the women killing birds with their hands to prepare food in clay pots on the wood. I saw a group of men returning who returned from hunting victorious with a tepezcuintle, a typical animal of the region, on their shoulders. I was amazed and delighted with that place.

There was a moment when I began to explore and walk around, and I found a waterhole where everyone bathed in the morning and washed their white robes, but suddenly there was a place that caught my attention, a palm hut in between all the trees and that emitted a very particular smell. When I wanted to approach that place, a large man with very deep eyes immediately stopped me, and he told me that this place was a sacred place where they performed their rituals and that I could not have access there.

Seeing me sad for not being able to enter, he told me the anecdote about the stars and the trees. For this community, the stars and the trees are connected. He explained to me that the stars hold the world with invisible threads that are tied to the trees and that for this reason it was very important to let them live until their natural death, because if you cut a living tree, you cut a thread that sustains us in the universe. In addition, they believe that every human being at death becomes a star to sustain the world, so if you cut a living tree it is as if you killed some distant relative.

It was from that memory where I extracted the name. In fact, in the album you will find small interludes called “Encuentro,” which are soundscapes that I recorded from the Lacandon jungle.

The album is also very cinematic. Do you perceive there to be a connection between the music that you make and video?

I like landscapes very much; I remember them in detail, the space, the colors, the textures, the aromas. When I compose, I glimpse the memories in very clear images and try to represent them faithfully with sounds and frequencies, so I do believe that my music has a cinematic essence. Also, since my previous release, I’ve started receiving invitations to collaborate with filmmakers, choreographers, and plays.

What else have you planned, looking forward?

For now, we are very focused on the official presentation of the album. There will be a performance in which we are working with a group of very magical girls and boys, and with my friend Lisboa Bear, a musician from Tlaxcala, with whom we are working to magnify the sound that day. We are also working with the rewards that we can offer in our Kickstarter campaign, including vinyl printing.

I have a lot of excitement and intention to get carried away by this new stage in Un Rêve, to present the album live and see where it can take us. I am totally open to sharing it with as many people as possible. This release has greatly activated my creativity and the desire to return to the stage, to continue collaborating with more musicians and friends. I want to grow along with music.

All photos: August Elias, unless stated otherwise.