In The Studio: Adam Collins (a.k.a. Omni A.M.)

We sit down with one-half of Omni A.M. to chat through the band's history, gear, and production techniques.

In The Studio: Adam Collins (a.k.a. Omni A.M.)

We sit down with one-half of Omni A.M. to chat through the band's history, gear, and production techniques.

Adam Collins has unwaveringly dedicated his life to musical exploration. From his rock beginnings to Omni A.M., the psychedelic electronic band he formed in the ’90s with Marky Star, Collins has held a firm focus on pushing the limits of sound and, more importantly, what a band can sound like and do. In creating their sound, Omni A.M. drew heavily from the moodier end of Chicago house and the forward-thinking sounds emanating from South London and San Fransisco, with wider touchstones like Fugazi and The Jesus Lizard creeping their way into the band’s genre-less fusion.

From the beginning, Omni A.M. approached electronic music with a rock-band-like mentality: first, you would record an album in live, one-take cuts; second, you would produce that album and cut it to cassette, CD, or vinyl to sell at the upcoming shows; third, you would play shows and tour the album anyway possible—more on that below; and finally, you would devise a new sound and sonic identity and repeat the steps. This traditionalist approach ensured that every piece of Omni A.M.’s output, from the record sleeves to the music and the way the music was presented, was artistically considered to create a timeless body of work—proof of this can be found in the exorbitant prices Omni A.M. records can fetch on Discogs, some north of €200.

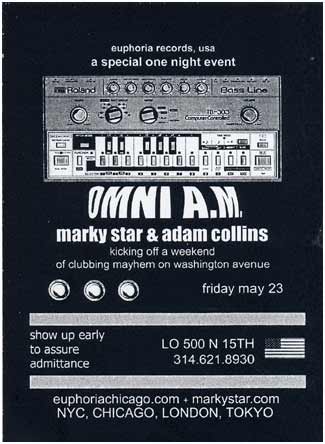

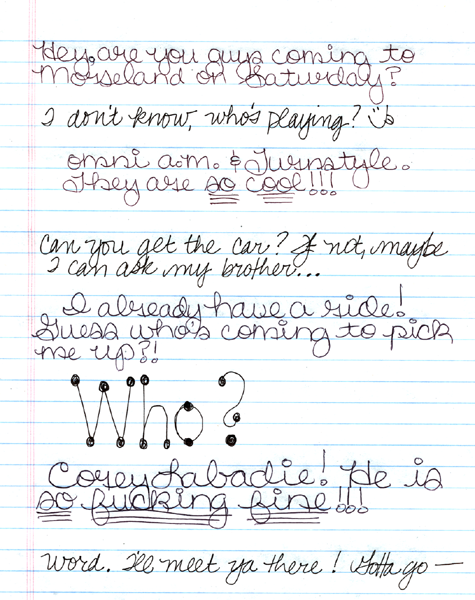

The majority of their work was released via Euphoria Records, the label created by Collins, Corey Labadie, and Marky’s brother Andrew, which was birthed from a party series of the same name that featured all-night psychedelic journeys from Omni A.M., with DJ backup from friends in the Chicago house scene. Still active today, Euphoria Records has become an outlet for the art of emerging acts from around the world, the latest of which arrived from Mindworks, a duo from Pretoria, South Africa comprised of Tshepo Lucky Macheke and Thabo Brian Maloka. The label, too, has been home to most of Collins’ solo productions in recent years.

With the rerelease of Omni A.M.’s Beat Dis now on the shelves—more represses are on the way via Cure Music and Was/Is—and with a string of solo releases on the way on Komuna Tapes, Cube Records, Nervous, and Giant Records, XLR8R visited Collins’ Los Angeles studio to muse on the band’s history, gear, production techniques, and what is to come.

The band have also offered up a free download of “Watching In Slow Motion,” recorded live in 1997 at The Double Door in Chicago, available via WeTransfer at the bottom of the piece.

Studio photos: Diana Dalsasso / Kulture Kick

CLICK PHOTO TO ENLARGE AND ENTER GALLERY BROWSING

How did you get into music?

I was always in rock bands and I played guitar. My entry into live music was with the guys I played in a band with; we were called the Proteus. We started in high school and played a bunch of clubs around New York like CBGB and some art museums. We all decided to go to Chicago for college to be around the indie scene; I went to The School of the Art Institute and the other members went to the University of Chicago. So we landed in Chicago and were making music there. At the same time, I was hearing house music on the radio and in the grocery store, all around. It was everywhere in Chicago.

Around that time, Andrew Hobold was introduced to me at one of my house parties. He said, “Oh you make music too? I make music, you should come over.” And I thought, being from a band background, that I would be going over to jam. A couple days later I brought my guitar over to his place and I was super excited, this would be the first new person in Chicago that I would jam with, you know? We go into his room and there is a computer sitting there, and a synthesizer on the floor. I was like, what the fuck is this, man? And he was like, “come in, we’re gonna work on music.”

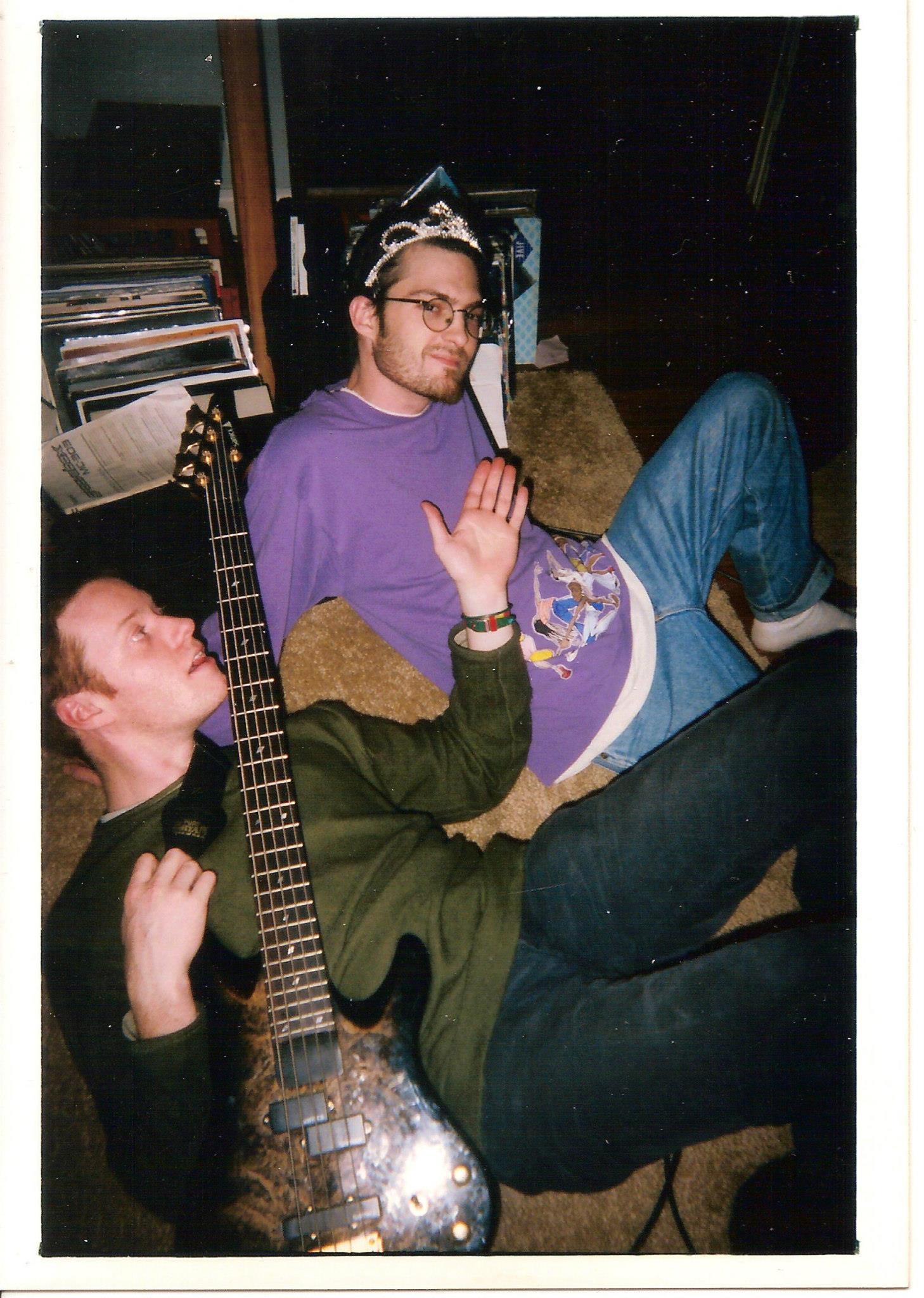

Working on music on a computer was just so strange then, I couldn’t get my head around it at first. We wrote three songs right away and still write music together. Andy was the person that introduced me to Marky, his brother, who I started Omni A.M. with. Marky came up to Chicago because he needed a break from being home in St. Louis. I really wanted to make music and Marky wanted to make music. I heard one of Marky’s tracks and I thought I could make it sound better, so I suggested mixing it at the Art Institute. From there we started working on music together. And that was the beginning of Omni A.M.

Who were some of the artists at that time?

Derrick Carter. 100% Derrick Carter. Chez Damier, Glenn Underground, Tyree Cooper, Fast Eddie, DJ Funk, DJ Dan, and also Josh Wink—there was a little bit of crossover from Detroit but it was all very Chicago heavy. DJ Heather too, I love DJ Heather, plus Cajmere/Green Velvet and Diz. I was also influenced by DJ Garth, Thomas, FSOL, The Orb, Deee-Lite and Cabaret Voltaire. Mostly Derrick Carter, though, and all the people associated with Classic that would come to visit Derrick to play in Chicago. It was really centered around him and Gramaphone Records. I didn’t know him personally at the time, but now I consider him a mentor.

So the first tracks were produced in the school?

They were, and my teacher Rob Drinkwater mixed the Key album. Like most other producers, we also used our bedroom studios where the majority of the recording happened.

So there were studios at the Institute?

Yeah, proper recording studios. I originally went for painting and photography but I got a little disenchanted with the program. I didn’t realize how expensive it can be to make art.

Around that time, the new sound department at SAIC opened and I was one of the first students. I was already in a band, so I thought, why not? From the moment I walked into my first recording studio with the Proteus when I was 16, I knew it was home. This is me. So I signed up for the audio program and no one was using the studios. It was there I met Chris Clepper (Tiptop Audio), who does Euphoria’s mastering and has been our main engineer from day one. He would give us new music and just be the technical side of post-creative writing. The other studio was at Mark’s apartment—the one he moved into with Andy and my girlfriend at the time. She wasn’t too happy that I was working on music over there so much, so she kicked both of us out of the apartment. Marky moved into my loft, which was next to the Double Door, and we began working on music full-time.

So what was the gear set up at that time?

It was a Roland MC-303 as the sequencer and drum machine; a Moog Prodigy as the bassline and the ambient noises; various tape machines; and a guitar and effects—that was our original first setup. From there, Mark added a sampler, an Emu ESI-32, which had 2MBs of RAM. We couldn’t believe the amount of recording time we had—mind blowing and futuristic. We added a Roland JP-8000 later. Roland and Moog were the predominant sounds for us.

Where was the first show?

Oh god. So, we landed on the name Omni A.M., it worked, sketched it out, done. Now we needed a show. I literally picked up the phone and called the Crazy Horse, a bar right around the corner from where we lived, and told them I had a live electronic band from Italy here in Chicago for one night and they must play a show. Mark spoke Italian so I thought for sure we could pull it off. We put on some crazy shirts and pretended to be a live electronic band from Italy called Omni A.M. Marky committed to speaking Italian and I would just nod and not talk at all. The promoter was so excited to have this live band from Italy, he was just amped up. He put us up on stage, we did the show and our friends all showed up. The show was going off, but something went wrong in the last song, the sequencer skipped I think. Mark goes, “oh fuck,” and I yelled, “what’s wrong?” At that point, it was clear that we weren’t from Italy. We literally lived around the corner. And to make it even more epic, our friends decided to throw towels over where our equipment was, then proceeded to walk out with everything, including cases of warm Newcastle Brown Ale. To this day, I still can’t even smell the stuff. That was our very first gig. Omni A.M.’s first show.

And you played regularly after that?

Yes, we played a few outdoor shows in Wicker Park and we made our own residency at a bar called Cleo’s, which wasn’t too far from our place either. Once a month we would do a party where Omni A.M. would play live. A DJ I went to school with, Shannon Dayhota—she was part of the Super Jane trio alongside DJ Colette and DJ Heather—would open the party and our roommate Corey would DJ. Omni A.M. would play a psychedelic set through the whole night. Those events turned into our Euphoria parties, which was how the record label started. Making all the original music and doing the shows, we decided to start selling the material at shows to our friends and fans. We made our own cassettes before we made our first CD before we made our first vinyl.

Was the studio set up roughly the same as the live setup?

Yes, exactly. At some point, we used turntables and began mixing on top of our songs.

How were you recording everything then?

On DAT through a Tascam four track mixer that we used. Our setup grew over time, but we never really transitioned to the computer. Everything Omni A.M. has ever recorded was performed live, just like a band. We were a band. The mindset that I came in with was that you practiced the song until you get it right. If you need to record six to seven versions of the song to get it right, then that’s what we are doing. I’m not going to sit there moving blocks around on a sequencer. It just didn’t feel like a band. We both came from the era of Skinny Puppy, The Orb, The Jesus Lizard, Cop Shoot Cop, bands like that. Fugazi. They could play. Fugazi and NIN could put on a live show. So we wanted to be the same. Like, you could throw anything at us and we would play it.

So how was it for Marky not being from that band background?

He brought the beats and the electronic element to it.

So he was handling the rhythms and you were the melodic stuff?

Exactly. Our process was, you write one part and then I write the next part. We would go back and forth, but Mark and I were all about the jam after a while. Mark is a really creative genius in the studio; I love working on music with him. It really became a question of how do we make this sound the best based on what we were listening to at the time. We were so influenced by all the stuff coming from South London and the Wicked crew from San Francisco. We were so into all that music and Mark wanted to feverishly write beats and so did I and throw it all together and take samples and just come up with lots of material. As much as we could. Always testing and pushing.

So you would jam around, find an idea and then beef it out and record it into a track?

We would practice it a couple of times and then record it. Our first album, Waters of Sul, which most people have never heard, was recorded from the beginning to the end, the whole thing live. And then Key came along, our first CD release. We wrote all those songs individually, coming out of our live shows, then took it back into the studio, layered it and mixed everything together in a full continuous mix. It was very representative of our live show because the beats weren’t just four on the floor, it was breaks and weirdness and big ambient interludes.

Then we thought, can we keep doing that? We had already been playing for a year or a year and a half doing the experimental electronic sounds and our friends were like, “we’re kinda tired of carrying your equipment around to all the shows, you guys have got to learn to DJ.” So we started taking in Chicago house and thinking about all the mixing. We wanted to be making records that we could be DJing. We thought, wow, what if Derrick Carter would play this record?! It wasn’t just him, it was all of our friends in the underground that we wanted to impress, you know? It’s always your peers.

So when did the first vinyl record drop?

We did Keep Doing That/Can We Get, which was recorded in 97. Even though that record says ‘99, it was written around ‘97 and finished in ‘98. That was the year Marky and I were graduating college. We had already been recording for a couple of years, but now it was time to make a record for DJs. Making vinyl was something that I understood from art school, it’s a lot like printmaking. It was a natural progression for us.

The Key CD was a great experiment. We sold out of it quite quickly between friends and selling it at our shows, so we thought it’s time to go from 500 CDs to 3000 records. It was a big jump for sure and we went for it. I came up with the idea to have a maze on the label and Jack Dove, our designer, brought it to life. Everyone still refers to it as the maze record. Interactive before the online times.

How did that record go?

It was really well received. It was the moment that I realized that people were buying my house music more than my rock music, so it was time to make the switch into house and techno. I was meeting so much more people with electronic music that were new and from all over the world. Being in Chicago during the late ’90s and making music there was a really exciting time. I feel lucky to have started there.

So do you think the house and techno world was more open and inviting to outsiders compared to the rock world?

If you were an outsider from any other part of your life, you were welcome in dance music. That’s an awesome feeling. Being a part of something, a movement. The thing is I am an outsider. I’m not born in Chicago, I’m never going to be from Chicago, even though that’s where I got my start. I still feel guilty calling anything I do Chicago house because I’m from New York. I knew I wasn’t ever going to fit into the hometown Chicago thing and I was OK with that, but thankfully I was accepted. Accepted for what we were doing and doing it on our own. No one was giving us a show, we had to make our own show. Nobody was going to release our records, so we had to do it ourselves. But we were accepted for doing our own thing and that’s dance music.

You probably wouldn’t have thought back then that a bunch of your records would be so sought after on Discogs?

I’m very humbled and honored by the prices people have put on our records and how special they feel about the records. We also feel that way about them—we really put a lot into it. We created the art with our friends and did the mastering and cutting sessions ourselves. We never handed anything off, from start to finish, even down to getting a deal with Prime or working with Swag Records. When it came to making the product, we were going to get something that you would look at in 5-10 years and go, that still works, you know? That was intentional. What people want to resale it for now, definitely not intentional.

I think a big part of that side of things is the internet and the growth of Discogs. The ease with which you can find things now.

Mark and I wanted to make something timeless, we didn’t want to compromise. In my mind, to be as good as someone like The Orb, it has to go to a certain level. There’s a hobbyist and then there is someone that is creating something with a full-on vision. I like to make paintings, I like to make prints and all types of art. The whole presentation needs to be considered. Like putting hidden messages in our records. We wanted to take it to the next level so that people were pulled in. And it doesn’t have to be trendy or anything, I mean, we had a puzzle on a record, that’s something a kid would do. But that’s the point, you remember it and you can use it in more ways than one.

And you mentioned The Orb as an influence, who else were some of your biggest influences?

Psychic TV, Ministry, Duran Duran, The KLF, Cabaret Voltaire, The Jesus Lizard. A lot of producers, too, everyone from Mark Ambrose, Terry Francis, Lee Perry and Keith Hudson. My rock background was The Can, The Doors—though Mark didn’t seem to like them—Fugazi, The Cure.

All of those acts are definitely at the weirder end of their genres.

Yeah, they pushed the boundaries. Omni A.M. is psychedelic music with funky beats, that’s what we are. Our thing was pushing the boundaries and breaking the rules within that. Why can’t there be a breaks tune with a house music sample, like in Beat Dis? It’s juxtaposing songs and sounds that make you think. I think Omni A.M. likes to exploit those areas quite a bit.

With Beat Dis being rereleased, are you guys still producing together? Are there plans for anything new?

With the spike in Discogs prices and the overwhelming amount of beautiful messages that I have received—a guy wrote me the other day: “Please can I buy this record off you so I don’t have to sell an organ”—we decided to repress. I don’t want someone to sell an organ—people obviously want this, but I didn’t want to cheapen what we were doing. Mark and I have never stopped working on music. Omni A.M. is always there, but we take music creation and our collaboration seriously. If someone appreciates what it takes for us to make a record, please contact us. But until then, we have already done some epic things, and Mark’s work in education and tourism in Japan is taking him to new heights. While he focuses on his blog Japan This, I’ve continued being a music producer and DJ myself. Omni A.M. still exists but we are not actively writing beats. Today.

So how do you see the distinction between Omni A.M. and yourself as a solo producer?

I believe it’s an extension. Just in the same way that LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy has worked with so many other artists over the years, or even a producer like Brian Eno recording so many influential bands. They put their talents into something and make the best product that they can, but that isn’t the only product that they make. Omni A.M. is just one of the projects that I am involved with along with House On Mute, Othersound, and Plugin Alliance. Omni A.M. may be what most people know me for, but I am nowhere near finished. I have so much more to contribute, learn, and give back.

So what’s your current studio setup?

I still use most of the same equipment from Omni A.M. and one of the drum machines that we added later on, the ER-1—it was very popular with the microhouse and minimal crew. We always really liked Korg products, I still have the Korg, the Prodigy and a lot of the keyboards from the original Omni setup. Our studio is split between New York and Los Angeles. My personal setup, I moved from the Roland sequencers to Cubase, then Logic, then Pro Tools, and now Ableton. I’ve used it all. Give me a toaster and I’ll make music on it.

So are you recording and Ableton is acting as the tape and sequencer?

I look at Ableton like an old school sampler. I cut everything into small samples and I lay it out in the clip mode to jam with. So what I couldn’t do with Omni A.M. before is possible now with Ableton. It’s all laid out in front of you. I mean, I wanted to have the touch screen before it was possible but I’m not making gear, it was just something that I wanted back then. Ableton is beautiful and so are the dedicated pieces of gear and the Eurorack modular setups that offer endless inspiration. I would also like to work with the Roland Boutique series.

So you would run your machines and record long takes or loops into Ableton and then cut them up and jam with them?

Yeah, that’s basically it, and I use the Novation Launchpad for launching the clips and jam off that. Everything is still live.

How else does track creation in your studio work?

I go out to events often and I listen to a lot of music. It’s always a great sign when you want to leave the party and go to the studio. I’m also very inspired by the sounds of nature, cities, and everyday life. Any of those sounds can be recorded, edited down and turned into a drum or synthesizer sound. I like to start writing a pattern on a drum machine and only use one piece of equipment at a time. This way you don’t get overwhelmed with options. The constraints of a single piece of gear like the Korg units help you make a solid pattern.

How long would you test tracks out when DJing before moving forward with releasing? Do you think that’s an important step?

It’s a crucial step in understanding what you release. Seeing the crowd reaction is a must. When someone comes up and says “This song is dope, I have this” and you’re playing it for the first time, release it now. But honestly, it’s all about how it sounds, how it makes the crowd move. Always test your songs on a club system to hear what’s working and what’s not. You’ll often be surprised how different it sounds in the mix. That’s invaluable information for making the final piece.

Would you master these briefly yourself before playing them? Or play just the mixed versions?

Both, to be honest. It’s good to hear what the differences are between mastering and mixed in a club or party setting. At times, gain volume on the mixer can offer the extra punch that mastering does. If it’s an important event or special sound system that I’ll be playing on, I make sure to do a master to provide the best possible level matching and quality I can. At the end of the day, it’s all about what’s in the groove, not how good the groove sounds.

Omni A.M. “Watching In Slow Motion” (Live at The Double Door Chicago, 1997)