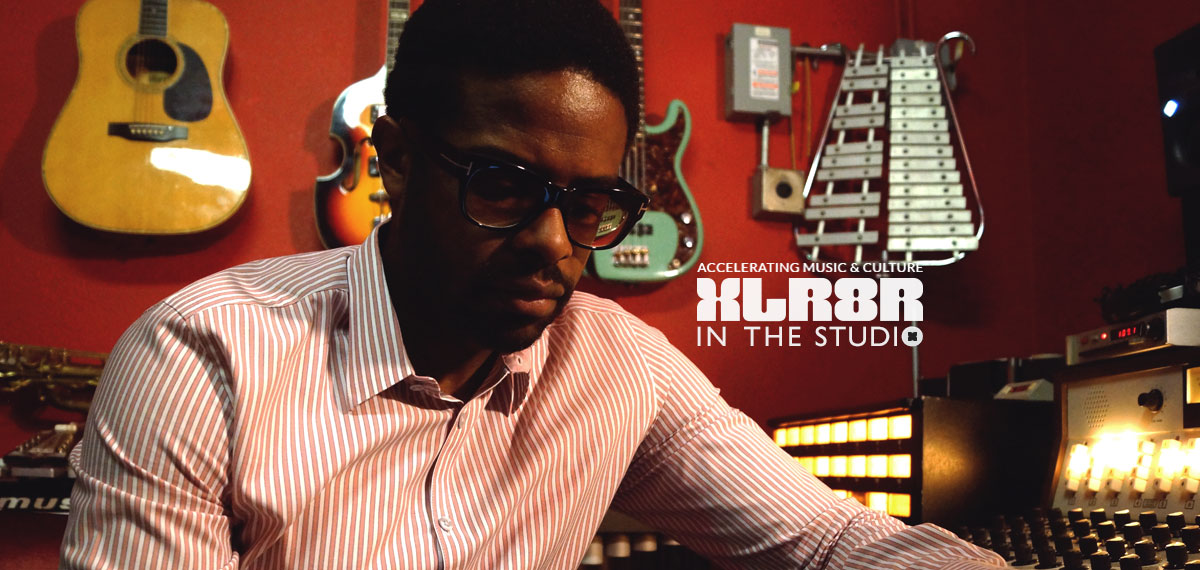

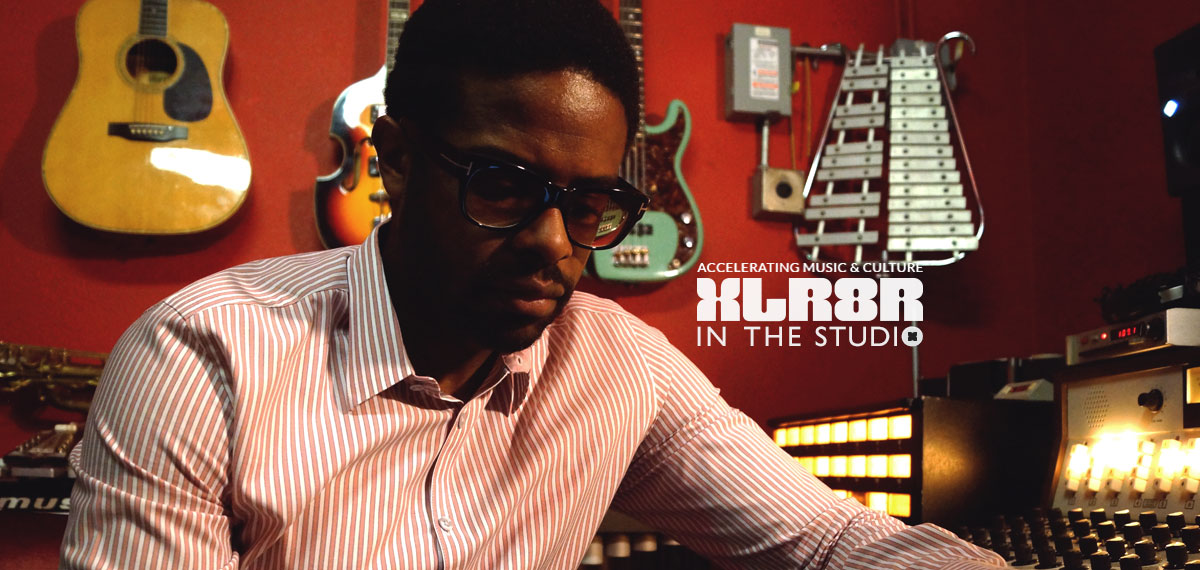

In The Studio: Adrian Younge

With a new album on the shelves, XLR8R visits the studio of the renowned analog wizard.

In The Studio: Adrian Younge

With a new album on the shelves, XLR8R visits the studio of the renowned analog wizard.

When it comes to analog production, few command the amount of respect, and know-how, that Adrian Younge does. Starting out with an MPC and inspired by hip-hop and the art of sampling, Younge soon realized, for his musical vision, he needed to create the samples himself—an audiophile epiphany, if you will. That epiphany has taken him on a self-taught route to a credential list that even the most seasoned of beatsmiths would envy. His tracks have been sampled by Jay Z, DJ Premier and Royce Da 5’9”, with the latter two exclusively using Younge’s music for their PRhyme album; he’s released a solo album, There’s Something About April, on which he played every instrument; he soundtracked and edited the film Black Dynamite; he owns and runs a record label and record store, Linear Labs and The Artform Studio, respectively; and he’s produced albums for Souls Of Mischief, The Delfonics, and Ghostface Killah—all of which he also played every instrument. In short, the man is a musical genius— one who has spent the best part of his life honing in on his singular vision of music: a raw, soul-infused sound that is hand-crafted from the myriad of holy grail-like instruments and recording equipment he’s acquired for his all-analog studio in L.A.

With his new album, Twelve Reasons To Die II, out now—and two more on the way in the fall—XLR8R visited Younge’s studio to talk analog gear, the creative process, and his highly-focused musical vision.

So Adrian, you’re a self-taught musician, producer, and composer, among other things—how did it all begin for you?

Basically, I started producing in ’96. Like seriously producing. I had an MPC 2000 and a Tascam 8-track Porta-Studio, and I started producing hip-hop tracks that were inspired by the living legend, luminary hip-hop producers of the time, like RZA, Preemo [DJ Premier], all these people. And when I was sampling these records, I realized hip-hop was introducing me to the source material, which would in turn kinda change my life and provide me with a new focus in music. I realized the music I liked the most was created with live instruments. So at that time, being somebody bread within the hip-hop culture, my mind was opening up and I realized my favorite bands were actually Portishead, or Air, or King Crimson, or the Beatles. Like there was this epiphany, like I realized that if I wanted to be my best I had to learn how to play instruments—but not just play instruments, but to compose in the way they would have back then, and also capture that sonic palette that they used. Because that sonic palette is very essential to the music that serves as a source material for hip-hop. So I put the sampler down and started buying instruments, and I would come home from college every day and just start playing. Start writing things. Because when you’re a producer, especially a hip-hop producer, there’s so much music in your head because you listen to so much music around the world. You know, cause you’re trying to find that cool, ill sample. I wanted to get things to the point where I could make the sample in my head, and play the sample, but not only play the sample, but open up the chorus and create a full on sonic structure of something that was just kinda trapped in my head. So that’s how I really got into it; that’s how I started out playing all these instruments. And in addition to that, when I made the transition to learning to play instruments, in like ’98, ’99, I never thought that I would be doing it all on my own. It got to the point where I learned how to be self-sufficient because I didn’t want to rely on anyone or have anyone slowing me down. Because that’s what was happening. People would say “Yeah I’m down, let’s do this.” And then never show up. So I said, fuck it, I gotta do my own shit.

It all must have seemed a little daunting back then. I mean, now you play all these instruments, but when you were starting out and teaching yourself to play, it must have seemed like a huge mountain to climb—that one day, you would be writing the music for every instrument on a record.

Oh yeah, for sure. I had an epiphany in ’99. I said I want to produce a whole album where I play every instrument. And my initial Venice Dawn album came out in 2000, and that was me proving to myself that I could actually do it, and I did it. And I even had to learn how to play stuff for the album. What I learned was that once you learn how to play one instrument, you can kinda play them all.

So what was the first piece of gear you learned on, your first instrument?

It was a Fender Rhodes. It was like a real beat-up suitcase model and I just came home and played it every day. And I was still living with my parents at the time, I was like 18, 19 years old.

How long have you been in this space?

About four years.

Looking at the gear in your studio, I feel like I’m in a museum. How did you acquire all of it? Has it been a life long search?

You know what, it’s a “lifestyle search.” You may wake up and check your email; I wake up and check to see what people are selling. Like a passion, dude. Like I’m addicted to gear that can inspire me to make music. All gear, when you touch it, should inspire you to make a whole song with that instrument, you know…or a whole album, whatever. So when I first starting getting into gear, I realized I was becoming a collector. I mean, there was a time when I had like 15-20 analog synths. But I don’t need 15-20 analog synths, you know? They were cool but they didn’t all speak to me like that. So I realized, if I’m not using something in a six-month time span, I have to get rid of it—and I would have to get something else. So where we are at right now, at my studio, it’s just the cream of the crop. Stuff that I just need and use on everything. And It took a while to get to this point, where it’s pretty lean—lean with essentials. So it’s like, “Why do you have this amp, and that amp?” Well, this amp does that and this amp doesn’t do that. Or “Why do you have this synth and then a double of that synth” and it’s like, well, if that synth breaks down I’ll just use this one, or this one is more special to me, so that one’s my tour one.

Can you take us through your most used pieces?

So this is my mother ship right here, the OpAmp Labs Board custom mixer from 1972. These were initially made for television studios and it’s all solid state, transformer-based—and it’s beautiful. It sounds excellent! The EQs are all conductor-based, and the sound of it is just ridiculous. I always tell people, when it comes to professional audio products, everything is just five-percent increments. It’s not like there’s just one thing where you’re like, “oh that thing is the shit, that’s what makes you sound dope.” It’s all incremental, like a five- or ten-percent incremental increase in sound quality based on what you use. I could have all this gear and have garbage-ass instruments and make something sound dope. Or have dope-ass instruments and garbage pro audio and try to figure out what I’m gonna do to make it sound dope, you know? It’s all perspective. So everything I have in here falls in line with my perspective based on what I’m doing. Because I don’t just do something that sounds psychedelic, or just something that sounds romantic—there’s different tools I use for different songs.

In regards to creating, do you have the vision for what you want to make first and then choose the gear?

Absolutely! Let’s just say for example, I’m making the Black Dynamite soundtrack. Or the Superfly soundtrack. There’s a certain type of wah I’m gonna use. I have dark wahs, and bright and beautiful, Sesame Street–type wahs. So it all depends on what the type of song is in that type of time frame. Everything I do is created from a time perspective, so if something is supposed to sound like it was from ’74, I’m not gonna incorporate elements from ’81 or ’82. I look at music in that it changes every two years…well at least back then it did. So, that being said, this is my baby right here. It’s a 16-channel recorder, and it’s 16 channels because I love 16 channels. I use 24-inch tape, but instead of using 24 tracks, I use 16 so I get a fatter sound. So I record on 16 tracks here, then mix on 16 tracks here, and then I mix down on my Ampex ATR-350 quarter-inch machine right there. And that sounds ridiculous! It’s all these little things that add to the greater sound.

I’ve noticed that most of the stuff that you’ve produced has a distinct narrative attached to it, is that what attracts you to the projects you work on?

Well, when there’s a story tied to an album, it inspires all the parties. So, I’m saying to you, “Let’s make an album that’s based on kung fu fighters in China, and it’s 1865, but we’re gonna act like it was filmed in 1981.” We want to create the type of sounds that they would have created at the time, but we want to make those sounds in the scope of an RZA. So if I said “You’re this character, and you’re on a mission here and these are all the stories, this is the narrative, this is what you gotta do,” then it inspires me to create the type of songs for that story and it inspires you as a vocalist to perform in a certain manner. So when we are limited to a certain story, it actually inspires us to try to expand upon that world. And when you’re expanding upon that world, it inspires you to do things that you would not normally do, because you’re now allowed the chance to do whatever the hell you can within that world. Absent of that world, you’re not gonna go there. Those songs are not gonna be made. You’re just gonna be freely trying to figure out, well let’s move in this direction, or that direction. When you have a narrative attached to something, you kinda know where to go. And it’s just like each song you do you get closer and closer to being in that world. So when people listen to my music, I like them to feel like they are taken to another world, instead of just singles put together on an album.

Have you always been inspired by narrative and film? You directed the clip for “Rise Of The Ghostface” correct?

Actually David Wong was the director; I’m an editor. So with Black Dynamite, I scored that film and I edited that film. On all the videos I do, I edit all of them. So I edit the films, but the director is my right-hand man. So we write it from an editing perspective and we synthesize the narrative within that, so that it actually looks interesting. Having the film component with me with what I do, as far as music is concerned is integral, because the type of music that I make is audio visual music. It’s music that should serve as score to whatever picture you can create in your mind. So when I can give you elements, like a story element, when you’re listening to this song and that song, it’s like you should be able to envision, “Oh, that’s this person getting shot,” or, you know, “Oh, that’s this person in love,” or whatever it is. I love how music can create an audio visual experience. To me, some of the best music is the music that does that.

You actually wrote the narrative to Twelve Reasons To Die?

Yeah. With Part One, I wrote the narrative—and in writing the narrative, I consulted with my close friend and band mate C. E .Garcia. And then on Part Two, I said to C. E. Garcia, “Dude, I want you to take over this narrative. I want you to write this whole thing, and I’ll consult with you this time.” So I wrote the first one and he wrote the second one.

And I read that on the first one you basically wrote the musical foundation for the album in two weeks, correct?

Well yeah, but put it this way, if that story wasn’t there, and I had to write the foundation for an album with someone in 2 weeks? I could do it, but as far as being inspired, and having a direction? If the picture isn’t ready to be created, you’re just not as inspired. But there was something I saw, something I heard in my head for that one. I was on fire; I just wanted to get it all out. Especially just working with Ghostface, you know?

I’ve heard a lot of other artists say that the limitless possibilities of modern technology can actually be a hindrance when creating music and art, and that by creating limitations, like narratives, time frames, and gear, it can actually open up your creativity and let it all flow.

Oh yeah, exactly! The ramifications that you set for yourself can inspire you to do things that you would have never thought of, because once you’re trapped, your job is to persevere. So I mean, hip-hop is based on that notion; hip-hop is based on the break. Sampling a certain part of a song and making that part of a song longer. So when you’re limiting yourself to whatever, whether it’s sampling, or instruments, or a certain recording style, it’s your job to persevere and actually make that interesting because you’re competing with other people that don’t put those kind of limitations on themselves. So, for myself, everything I do is analog. I don’t do anything digital. Everything is analog and that’s a limitation for me. However, in my world, it’s not a limitation at all because I don’t create the type of music that would generally be created by musicians that work with digital recording studios, and/or digital equipment, as far as production is concerned. It’s not to say that what I do is better, because I don’t feel like that at all. I just feel that in order to do what I do, there’s a certain way I must limit myself. I can’t use plug-ins, and everything I do has to be live, like they would have done back then. And those are just the rules for me. But those rules help to differentiate my sound to other people that, for lack of a better word, do “retro-style recordings.”

So how has your production changed from Part One to Part Two?

Well, to me, the Ghostface Part One is more of an introduction—Part Two is the real story. Because, just sonically, it’s darker and deeper. There’s way more to this story now than in the first one. I’ll give you a rundown: In Twelve Reasons To Die Part One, Tony Starks is a member of an Italian crime family. And in order to rise through the ranks he had to be Italian—but he was black. So he broke off from the DeLucca clan—which is an Italian family—and started his own criminal faction, and they were at war. And during this war, Tony fell in love with the wife of a DeLucca crime boss and they had an affair. One night she lured Tony Starks to a meeting at an old record plant, and when he went to the meeting it was sabotaged by the DeLuccas, and they killed Tony Stark’s men and Tony Starks by burning him in a tub of acetate, and they made twelve records as souvenirs of his death. And whenever the records were played, the spirit of the Ghostface Killah would come out and kill them all and seek revenge. So basically, that story was how Tony Starks turned into the Ghostface Killah. So that was in 1968, when part one happened…as if the shit is real. So Part Two is in 1974, and the De Luccas are in New York, and these are younger-generation DeLuccas. And Raekwon, who is starring as Lester Kane, is running the streets in the ’70s. And he’s a crime boss, just like Tony Starks was. He’s at war with the DeLuccas, and during the war, they end up killing Lester Kane’s wife and kid. So, I mean, he really hates them. And he always knew about the legend of the Ghostface Killah, but never knew if it was real. He and his men invade the De Lucca safe house and actually find 12 sealed records. So Raekwon played the records to summon the spirit of the Ghostface Killah, and he comes out and says “I’m down to help, but if I help you get rid of the DeLuccas, you must give your body to me so I can become human again.” And based on the circumstances, Raekwon says, “I’m down.” And during their war with the DeLuccas, Raekwon notifies Ghostface that Logan, the girl he had an affair with in Italy, now lives in New York and, unbeknownst to Ghostface, he has a son—Tony Starks has a son. So at the end of the story, after they’ve killed all the DeLuccas, they’re all in a room, it’s Raekwon as Lester Kane, Ghostface, his son, and Logan. And don’t forgot, Logan is the one who set him up in the first one. So Raekwon kills himself so that Ghostface can take over his body. But Ghostface decides not to jump into his body, but to jump in the body of his son. And he kills his mother, Logan, and Tony Starks is now alive again…as if we’re leading into Part Three or something. And I really wanted to tell that with the music. I wanted people to hear the music and feel where this story would be going. So like I said, going back to this concept of limitations, I limited myself to what they would have done in ’74 had it been on an Italian film, placed in New York at the time as if an Italian composer like Ennio Morricone hooked up with a RZA and had him as one of the producers.

One of the things that I really noticed on the album was the nuances that show up in the music—not only from playing analog instruments, but also with the analog recording as well. For example, in the track “Get Money” with Vince Staples, the most interesting part of the bassline is all the finger slides and slight imperfections. It’s what gives it its character, and I think that’s the beauty of the way that you produce and record.

Thank you. I wanted to create something funky, but “Sparks” at the same time. Not something with too much going on, but just like you’re focusing on the syncopation and the beat…like everything is just hitting each other but it’s not a constant chord. Like everything kinda bouncing. And I wanted that to inspire the MCs to go certain ways, and they did, so I was happy about that.

We recently did an interview with a group called Cobblestone Jazz who said “With modern production and computers, you can lock something into key and it will all be sitting perfect, and nothing out of place. But some of the best parts of music are some of those in between notes that you accidently hit, the sliding of the fingers to get to those notes”

Well yeah exactly. So this new album is coming out on my label, Linear Labs, and it’s based on a mission statement: delivering handcrafted, bespoke music that is perfected with human error. I love human error, I love shit to be a little off. It’s the ownership of what’s off that’s the beauty in art. Its not about being exactly perfect. When it’s perfect, it loses the edge, you know?

So that was another thing that I read that you had said, that when you are mixing tracks down, you try to not be too surgical or too perfect, to give it punch and thickness?

Well I’ll elaborate on that. What it really is is that I’m inspired by the source material of hip-hop. And the source material of hip-hop is essentially music that was recorded in a way that was not necessarily of the most professional standard of the time. So if you think about the most classic breaks of music, some of the most classic samples, that were not major-label releases, the drums are crazy loud. Or the bassline might be super fat. The vocal might be all the way on the left speaker, so you could just sample that one. Or the guitar might be super twangy in a way that a major label wouldn’t have even thought about releasing it. But it’s those weird things, that’s what inspires my mixing techniques. I mix in a way that is absolutely wrong, but in a way that is right for that sound. Like, your drums are not supposed to be super loud, because your snare frequency is usually in the same frequency as your vocal. So how are you gonna have a fat-ass snare and a big vocal? Its like, I do everything that’s off as hell. I have a ton of midrange in my bass, and if you have a ton of midrange in your bass then that’s meant to clash with your other chords and those other mid range frequencies. But I’ll record my chords and piano so that those frequencies don’t clash with the midrange of my bass. So its like I’m doing everything wrong to make a right sound. And that’s what my whole studio is kinda geared towards.

Something that I found really fascinating in the short film by Malik Hassan Sayeed and Arthur Jafa—which can be seen here—was that you were looking for a dark, RZA-like sample, and you found the sample, but rather than use the sample, you chose to recreate it by getting into the mind of the band who played it…who you said were an eastern European band that were trying to be the Beatles, but weren’t quite good enough.

Yeah, so basically, I don’t sample. Everything I do I do live. So when I’m creating music, what I say is that I’m sampling music in my head. And then I put the facts together: Who are these musicians? Who are these people? Where are they from? So if I’m listening to American soul funk”from ’72, and I listen to Brazilian music at the same time, it’s not gonna be the same. Because they’re gonna be like two or three years behind. So I think about thing like, am I a Brazilian dude in LA, and how am I playing these congas? If I’m playing drums, am I supposed to be someone who is a very tight proficient drummer? Or am I meant to be the homie who kinda plays drums but has a nice little syncopation to his hits? These are the things I think about because I’m playing these instruments as separate musicians, not as Adrian Younge. So it’s like, if I’m playing guitar, or bass, there’s certain things where I’m going to be, like in “Get The Money” where I’m going all over the place with the bassline. Or there’s certain times where I’ll be like, well, what would RZA do here? He would just keep it simple like “booom chh, bo booom chh, bo boom”—alright sweet, I’ll just do that. You know? So I’m in characters all the time, and these characters are inspired by many of my favorite composers and producers from the decades, like Isaac Hayes, RZA, Preemo, all these people. So I’m looking at all of them, as if I have them in the room. But it’s really me doing it.

So back onto the gear, you said that your gear and your studio has been a lifelong obsession, so is there a piece, or instrument, that is like your unicorn? Your holy grail? Something that you really want but haven’t been able to get yet?

Actually, no. It’s funny man, because people are generally always looking for a sound, right? Well I’ve found my sound. So it’s like, I’m so happy with it all. I don’t have to have one more piece of equipment for the rest of my life. But that doesn’t mean I don’t buy gear. Because I’ll be like, ohh that would be dope to have in addition to this, or in addition to that. I’m straight, though, when it comes to gear; there’s no real holy-grail type piece that I don’t have that I want, because I have a lot of holy-grail type stuff already. And I’m like the dude that gets one thing for one purpose. For example, those black compressors, those are old tube compressors that were actually made for television, but they were military spec. Those I have specifically for vocals and specifically for bass. That’s it! And there are certain things they do just for that. See what I’m saying? Like, I’m dialed in like that for everything I have. This reverb I use just for certain things, I use that spring just for certain things, you know? So I’m dialed in now, but there was a time when I wasn’t dialed in, where I had these holy grails. But now I got the holy-grail shit so it’s just time to make music.

When did you start your label, Linear Labs?

Well, Linear Labs was officially started last year with the Souls Of Mischief album There Is Only Now. Second was the Los Angeles compilation that we just released. And the third release is this new Ghostface Killah album.

So you released the original Venice Dawn piece as Adrian Younge, but now your band is also called Venice Dawn, right?

Yeah. Remember when I said that I wanted to release an album where it’s me playing all the instruments? So in ’99, I made that album and released it in 2000, and it was called Venice Dawn. And it was supposed to be a fake Italian movie from ’69. So when we performed back then, the band would just be called Venice Dawn. So now the band is still called that. And on all my albums, even though I play all the instruments, I always make sure I have the band on the album, because I always want them to feel vested in what I do. Because these are my people. So that’s where Venice Dawn comes from. It was the title of my first album and now I use that for the title of my band.

What else do you have coming up?

Well, two weeks ago I had an album released with Bilal. Last week, the Ghostface Album. In the fall, I’ll also have another album with Ali Shaheed Muhammed from A Tribe Called Quest. Its called The Midnight Hour. And that album is essentially the kinda stuff that A Tribe Called Quest would’ve sampled had this music been made before, but with modern artists like CeeLo, Bilal, Marsha Ambrosius, Common, like a bunch of people. Then, I have my Something About April album coming out in the fall. So these are the next four albums I’m focusing on.