In the Studio: Levon Vincent

The detailed secrets behind the American's sound.

In the Studio: Levon Vincent

The detailed secrets behind the American's sound.

Levon Vincent has been producing records for nearly two decades, starting in Manhattan, New York. His music taste and processes were shaped by early ’90s house music and the energy that surrounded him in places like the Lower East side and Alphabet city. The explosion of music sampling in the ’80s informed his processes and, influenced by the elder producers in his orbit, he began his own experiments using an Ensoniq EPS-1, one of the first few affordable samplers on the market. He released his debut EP, No More Heros, in 2002 via his own More Music NY. “I have quite a lot of experience as a student,” he explains. “I’ve never shied away from tracking down a producer or engineer to ask them 100 questions.”

Vincent’s ensuing releases landed with regularity: Complicated People and The Thrill Of Love came next, with a slick, warm house sound, before 2005’s Love Technique saw Vincent present a harder acid-infused techno aesthetic. This evolution continued as his signature became dark, chunky, and raw but groovy, psychedelic, and, well, sexy—at once driving and meaningful. “It can make you dance and it can make you contemplate,” says one enthusiastic Discogs user. (Case in point: “Double Jointed Sex Freak.”)

The culmination of this came with 2015’s self-titled album debut, a release—offered as a free download as a stand against the corporate machine—that exceeded even the huge expectations that surrounded it. It spanned atmospheric dub techno, lush deep house, and explorations into the darker realms, cementing Vincent’s reputation as one of the most original producers in contemporary techno. Often it takes two or three listens to properly understand his message; to really appreciate how he says so much with so little.

Vincent has been hard at work recently, preparing a series of EPs that’ll drop this year, expected to be one of his busiest yet—his first release of the year was “Dance With Me,” an old-school house cut on the January edition of XLR8R+. After some informal exchanges, he invited XLR8R into his studio, located in the spare room of his spacious Berlin apartment. He’s always been a bedroom producer, so this is where he feels most comfortable. Although distanced somewhat from the analog heavy lairs that we see so often in contemporary production, there is some seriously heavy duty equipment. “I am proud to be a bedroom producer and not too flashy,” he says. “This is independent music and should be in the hands of anyone who wants to make it.” To learn more, we sat down for a lengthy and candid discussion with Vincent, and below you’ll find a (slightly) shortened version of what was said.

To start, can you describe your current studio setup?

Today I am working with a few Roland synths and a Jomox drum module. For tracking, I use a combination of Aurora and Great River pre-amps and UAD conversion. For mixing down, I use JCF conversion, an SSL G-series compressor clone, and I sum through the Chandler mixer. I am a fan of the DSD (Direct Stream Digital) format and I use Korg and Tascam recorders. I own a pair of trusty US$30 Logitech multimedia speakers, as well as a monster pair of Barefoot monitors for reference purposes, and some other goodies.

I’ve put any profits over the years into recording gear so I’ve really cherry-picked the exact items I need. I went through a lot of extra items while figuring it out and now I am down to just what I need, so if there is a piece of gear in my studio nowadays, I use it. I don’t have a synth museum or anything; those setups come and go for me, depending on my disposable income at the time. I also use a Yamaha digital piano, and while it’s nice, I left a Kawai MP7SE stage piano in New York when I moved to Germany, and I miss that one a lot.

Has your setup changed considerably over time?

My setup is constantly changing. Not the recording gear—it’s too important—but the instruments always change. I usually buy a few synths, make a record or two, then sell them on Craigslist and repeat. Overall, there is less equipment now; I choose not to have an exorbitant amount of sonic “toys” at the moment. I will start buying again soon, just a couple things here and there. I am holding out for Behringer to announce a Jupiter 8 clone.

Why do you feel the need to constantly change the gear?

Hmm, good question. I like that first feeling you get when you put a couple of synths together and you learn what type of personality they have. That comes from reading about Miles Davis, how he was so widely recognized as having a knack for putting band members together. I always liked that concept, so I enjoy the skill of combining different synths and drum machines. So a Walforf Pulse might have a very muscular character. That would be a nice compliment to a Juno, which has a more buttery sound. Mixing and matching the different instruments is akin to orchestration.

“..an artist must believe in what they are doing because there is a great sacrifice involved in dedicating your life to music or the arts.”

You spoke earlier about how you learned a lot from apprenticeships in New York. What are the most important lessons that you reflect upon?

This might sound like a negative but it actually was a positive for me: one lesson I will always remember was when working for the engineer on Steve Reich’s Violin Phase recording for Nonesuch. And I had spent several months with him but he had never heard my music. Finally, the day came and I played him my CD. He listened, and I asked him what he thought, and he said, “If you weren’t in the room, I would throw this disc in the garbage.” Sounds like a tough one, right? But it gave me a thick skin—it was better than being coddled and that experience forced me to evaluate what I was doing. I do believe it was good music, and I did release some of it on Novel Sound to great success. So, one person’s trash is another’s treasure. But I had to go back to make sure I really believed in what I was doing, and I learned pretty quickly that you have to take things with a pinch of salt if you are going to succeed; an artist must always believe in what they are doing because there is a great sacrifice involved in dedicating your life to music or the arts. It can be a frightful leap to take because you never know if you will always be able to eat properly, or sleep in your own place, or have health insurance, etc.

It’s interesting that your studio is still in your bedroom. Do you want an external studio?

That has never appealed to me. My space is very personal and it is a very important part of my work process. I like smoking weed and working, getting all dubby—and I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing that outside of my house. Also, I often wake up in the night with an idea and go immediately to the piano. That happens every couple of weeks, where I have a good idea in the night, and just jump out of bed and go immediately to working on it. I have written every song I have ever released in my bedroom. I wouldn’t want to work anywhere else. Well, now I use an office room in my flat and not my actual bedroom, but you get my point.

If I can’t make music with just 18 simultaneous preamps then something is wrong with my approach.

It doesn’t look like the most organized of spaces.

Yes, I do have a bit of a sloppiness problem with my work area. Not dirty, just messy. Truthfully, the messiness is a habit I developed from collecting records—just having too many records, the hoarding aspect. At one point I had 17,000 records. I didn’t even know what a few crates were. I also collected comic books and graphic novels when I was younger. I like collecting things, as long as it doesn’t disrupt my life. The way I learned to conquer the vinyl addiction and manage the hoarding is by first getting rid of that entire collection. It was difficult but a very healthy thing for me to do. And now every few years I give away several crates of records. I’ve passed out gear too. It frees you up. Regarding the equipment, I have always been buying and trading gear. The 1990s were worse because I worked for a music instrument shop and was able to buy things at cost. That got out of hand. For the past 15 years or so I have had a “no patch bays” rule: I have 18 inputs on my preamps, and that’s it. If I can’t make music with just 18 simultaneous preamps then something is wrong with my approach.

Why do you think you’re more drawn to recording and processing equipment more than instruments?

Well, I was born in the ‘70s, and I came up in the ‘80s, and the era was dominated by sampling technology. It was a revolution. Synths are cool too, they are the instruments that belong in the studio. I love it all. I love a good machine—I always have time to appreciate a piece of gear that is designed and assembled well. I realize that I like machines that do one thing really well. I’d choose an MPC if I could only have one piece of gear. That’s a New York thing. Although I moved to Germany 10 years ago and haven’t looked back, some things stay with you throughout your life. I will always have a fondness for recording gear and old samplers.

Are you still sampling a lot nowadays?

Nope. December would be the last time I sampled my synths or drum machine. I sampled my Moog Source most recently, three octaves worth, and layered it with noise from the Anamod ATS-1. The result was a really fat sounding disco bass patch. It sounds like the octave bass from “Blue Monday.”

Why do you think your practices have changed?

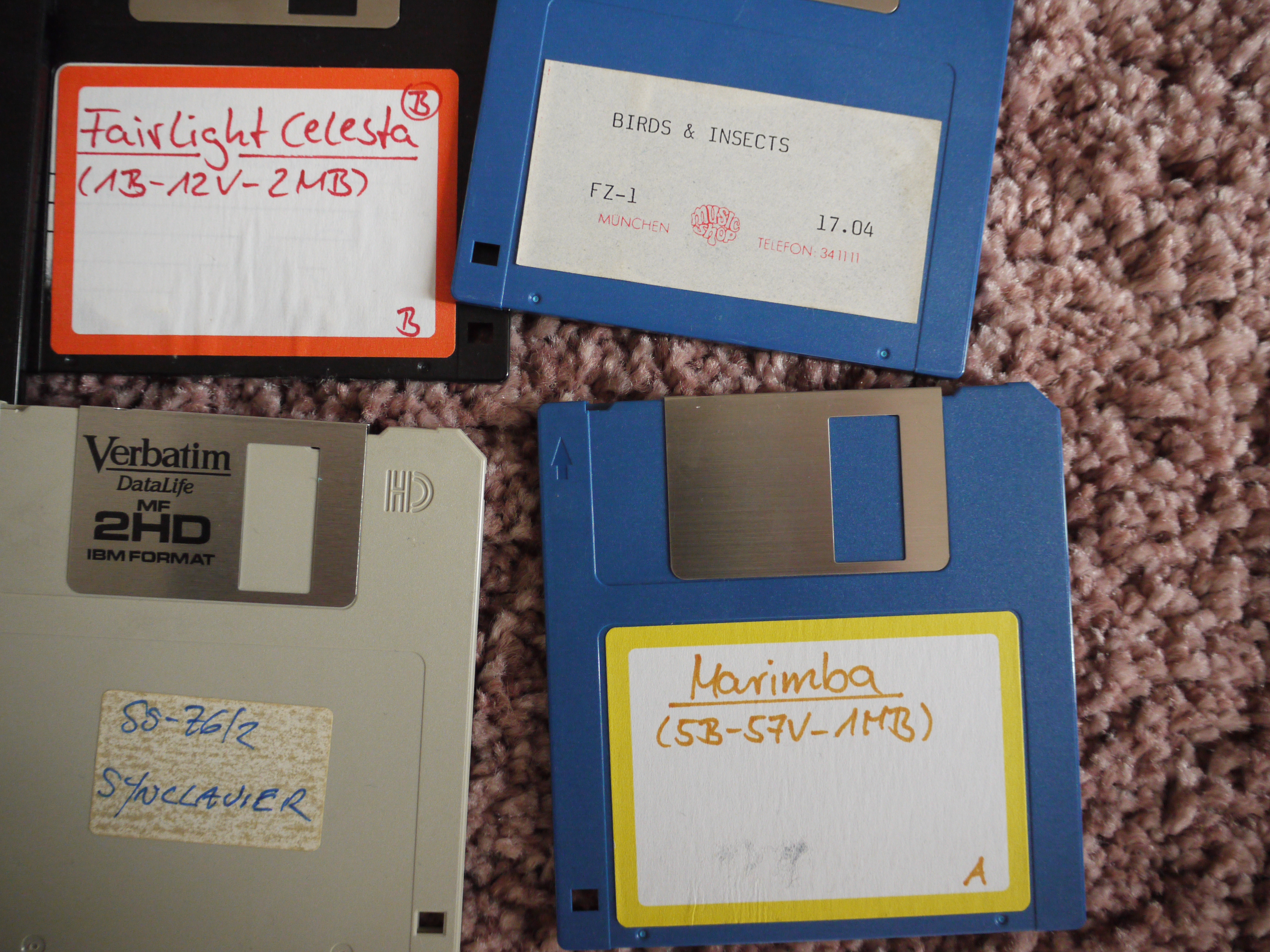

It’s because my library is so big now. It’s more important for me that I update what I have and bring it into the present time. Like my FZ-1 diskettes, I need to update those, and I have a bunch of zip disks to deal with, etc. I have an enormous library of 12-bit drum samples that I could use to make some really cool personalized drum machines. That’s something I really love doing—making my own drum kits, and then thinking of and treating them as if they are a rare drum machine, one that only I have. Then, I will spend a month making beats with it and really getting to know the sounds and how they work. I also like to pilfer the Jomox module, which is really punchy, and combine it with bits from my older kits. I sampled the hell out of my long-gone Linn Drum, for example. So I might take a shaker or a Tambo from that archive. Something I go back to a lot is a DAT of a Roland TM-404 drum machine that someone gave me in the ’90s, which was a prototype model that never came out commercially, and I sometimes mix a few sounds from that machine too. In the end, you have this really unique drum kit, which is like your own personal beat machine, and it’s cool to assemble your own drum kit because there’s only one “drum machine” made, so it’s like having serial number #001.

Do you think what you’re looking for with your setup has changed considerably since your New York days?

Yes, because I have grown a lot since my early days with production. It’s been a great journey. These days I have a higher success rate when working and I know what tone I like. An artist’s approach to their tone is one of those areas of audio that is regarded as esoteric since a lot of the boutique audio gear is subjective in its fan base and their opinions. So much of what makes a good record for me is in the areas of tone and timbre, but trying to explain what makes my clocking system so important is not always as readily agreeable as say, mentioning a Prophet V, which is a universally recognized work of art. I also reference my VU meters these days, which is something I ignored for a lot of years and regarded as a rock approach, where you are mixing live drums etc., but it’s an equally pleasant approach for dance music, making sure those meters are gently riding rather than jumping all over the place.

Are you currently using any in-the-box instruments?

I am a big fan of Native Instruments’ Kontakt. I have 25 years worth of my own samples stored on about 300 floppy disks, which I need to convert to Kontakt since I sold my Akai S6000 recently. I am already thinking about just buying another S6000 though. Otherwise, I will take the plunge and buy a copy of Chicken-Sys Translator. Then I can convert all my Ensoniq and Casio floppies too, so even though it might take a week or two of studio time, I would only have to do it once to be future-proof. The main thing is finding a way to preserve my aging library because I have put so many years of work into it.

Software-based instruments are awesome but can also be a point of contention for me due to struggles with timing issues. There is a competitive race to create the most extravagant, over-the-top-sounding beast of a synthesizer plugin but these instruments require buffer sizes of 256 Kbps or higher. This is unacceptable. If I can’t run my sequencer at 64 kbps, or maximum 128, then I will use a hardware sequencer instead. I can make music more reliably, whether it be with hardware or software, when working with small buffer sizes because I like to play instruments in real time—that’s why I like hardware samplers. I also like getting piano sounds or Rhodes sounds from my Korg TR-Rack, for example. Those are ROM-based machines. There are all kinds of sound generators. Analog synths are cool and fun but I generally don’t use more than four simultaneously. They are always necessary for funky and nasty bass lines, however, that’s a department where I really feel they shine.

It’s funny because I have made some of my personal favorite songs with delay compensation completely off, and a buffer size of 64. I like to work without delay compensation engaged because what you hear is what you get. I don’t like to disrupt the timing because I like to play my instruments and I want that snappy feeling. I hope that with the advent of the ELK system we are going to be able to use software instruments from within a Eurorack at extremely low latencies. That is tech worth paying attention to as it develops. That could really be big.

Is there any particular piece of gear that you feel like you’re missing?

I really like the Deckard’s Dream synth. A number of notable producers have expressed their happiness with that synth, Ellen Allien, for example. One of my “grail” synths would be an Ensoniq Fizmo in a rack. Also, Armen NYC refurbishes Akai MPC60s with hugely upgraded RAM and storage, new buttons and everything mint. That would be ace. I mostly would be happiest this year with a pair of racked Behringer Jupiter 8s. Dare to dream, right?

You’re rolling out EPs pretty quickly at the moment. Is this a good time for you?

Yep, I am in a good place. 2019 is off to a great start with regard to Novel Sound. It’s a dream come true to release music professionally. I always tell up-and-comers it is completely worth all the work to become a producer and touring DJ. Music has so much to give, and there is always something new to learn. On top of that, we are in the midst of a technological revolution. If you survey the history of music, we are in one of the most innovative eras ever.

“I have made plenty of sacrifices in life over the years, worked shitty restaurant jobs to get by when I really should have been doing music, etc. But with my music, I have a clean history.”

How do you maintain quality when you’re releasing so frequently?

I have a rule not to take any short-cuts, musically speaking. I put everything where I think it should be, and I won’t accept lazy decisions from myself during the process. There are, of course, mistakes, but I have managed to adhere to a strict rule: never compromise with making music. I have made plenty of sacrifices in life over the years, worked shitty restaurant jobs to get by when I really should have been doing music, etc. But with my music, I have a clean history.

Do you perceive this to be a purple patch when it comes to music making?

Not really, because I have never had to deal with writer’s block. There is always something for me to do, even if it’s just cutting up recordings of previous sessions. I truly enjoy all of it. If I were to describe my own catalog as I have experienced writing it over the years, I would call it a steady trajectory rather than ups and downs. I am dedicated to music, and each time I work I get a little better. There is so much to learn. You get out of music exactly as much as you dedicate and the coolest part is sometimes you can sit down and listen back to your catalog and it’s like a type of journal. You can hear where you were in life, or maybe one song will remind you of someone you loved, or writing a song in a flat you really enjoyed, etc. And that’s so cool because it’s such a bonus.

What does “Anti-Corporate Music” take you back to, and even that whole album?

It was really just about enjoying life, my enjoyment of life and the joy that DJing and music have given me. The song title, of course, is more serious but the music and the LP was an expression of a joyous life. Actually, when reviewing life and my catalog, I can give that same answer for pretty much any release! Did I mention I enjoy making music?

Do you remember the processes behind this particular track?

That’s an example of a track where I wrote the beats first, and then I became obsessed with making effects stand as a valuable musical element. I had this idea at that time about building an effects chain that you wouldn’t want to change for months, like one delay so elaborate and that would give such a rich tone that the effects in itself would be a type of composition. It was like a Rube Goldberg of reverbs, flangers, and other pedals, all for this one dedicated effect. When I look back, I always like those effects and how thick they are. I still use that approach today some times, where I put everything I have into one effects chain and then write around that.

Did you expect it to be such a success?

I had no idea. The actual reason I gave that tune away as a promo before the LP release was because the digital was a different version than what was released on vinyl and I wanted them both to make it to the listener. Honestly, I still get quite surprised by which tracks find success. The first track on my latest release on Novel Sound #26, the Dance Music EP— that record sold out faster than anything I have done in years, and I almost did not include the tune that people are playing right now. You really never know what will happen. That’s always so exciting about watching a record release.

I always notice that your tracks are filled with all sorts of inspired melodies—warped, melancholic, tense, foreboding etc. Are you playing these separately live? Or sequencing and tracking them along with the drum-machines?

I work alongside drums most of the time, especially for improvising. Lately, however, I have been writing the melodies first at the piano before I turn any other gear on. When you write the melody first, the result will be more songwriter style because you can do the harmonizations and other things like tuning your drums all in support of the melody. The result is, therefore, a melody-driven tune. For other tracks, more grooving and in the pocket tracks, you can make the drums first and then play alongside them as they loop around. One approach is not better than another. You can also let chance take part. For example. John Cage used a pair of dice with his notes assigned to a corresponding number on the dice, then he would roll and let them “write” the melody for him. That approach can be used not only for melody, but you can make the kick #1 on the dice, the snare #2, open hat #3, etc.

“I’d say a lot of my songs—most of them, actually—are the result of experimentation, I really like to answer the question ‘what if?'”

You’re clearly open-minded when it comes to production.

I need to be. There’s no one way to approach music: you get different results from different processes so I orbit different modes of working and I enjoy the variety. Sometimes you sit down and write a tune, or other times you just jam. Occasionally you enter with prepared ideas. Ideally, you are just sitting there and something comes over you. Those are the best moments in music, when you seem to be channeling something bigger than you. I’d say a lot of my songs—most of them, actually—are the result of experimentation. I really like to answer the question “what if?” So, “What would it sound like if I did this?” Then I can go into my room and work to find an answer. I am productive when driven by curiosity.

So how much is jamming and how much is actual writing songs, from left to right?

I bounce between the two. Sometimes I will write melodies on paper, other moments I play them out by ear. Arrangements can be done on paper, too—I like doing it that way because you can map out Phi points and use them to accentuate parts of a song. You can easily sit down with a pen and paper, and work out the Golden Mean, the Fibonacci sequence, or Harmonic series, then use it in your music. There are a number of patterns in the big Euclid book, or from visual art textbooks, etc., all of which can be applied to pitch, loudness, timbre, or duration. I actually made a frequency chart, which I rely on heavily for all things equal-temperament. I have a giant one on the wall in my house.

Can you explain more about how you incorporate these visual art elements or non-direct musical theories into your work?

I like abstraction methods and impressionism and I use those techniques in my music. For example, recording sounds in nature or city areas, then using those recordings as templates for sonic events. Or, if you think of “La Mer” by Claude Debussy, how he created the sound of waves crashing by playing on the piano—that’s musical impressionism. You can take that further using today’s technology, and make literal abstractions of recorded sound effects and environments. So, if he was writing “La Mer” today, he might have first recorded real waves, then used them as a template for his sound. It’s taking the feeling of inspiration from his great work and thinking about how to update that concept using software like Logic or Tracktion.

How would a producer incorporate this chart into their practice?

The Novel Sound reference chart lists the note and corresponding frequency. So, for example, if your bass line has an Eb which is too prominent and needs to be tamed, you can look quickly to the chart to know which frequency to dial up and attenuate. Or, if you want to make that note warmer, you can refer to the chart for the fundamental, and then either boost some even numbered partials or reduce some prime-numbered ones. Even-numbered partials are where the warmth resides, and prime-numbered partials give you “edge.” It’s also interesting to look at what frequency resonates with you sometimes. I find that it helps you to get to know equal-temperament intimately, since it makes up so much of Western music, for so many centuries. If you strike a note and it moves you, look at what frequency you just played, and think of how it makes you feel. Eventually, you know what you like or dislike with a broad range of notes of combination therein.

Can you give an example?

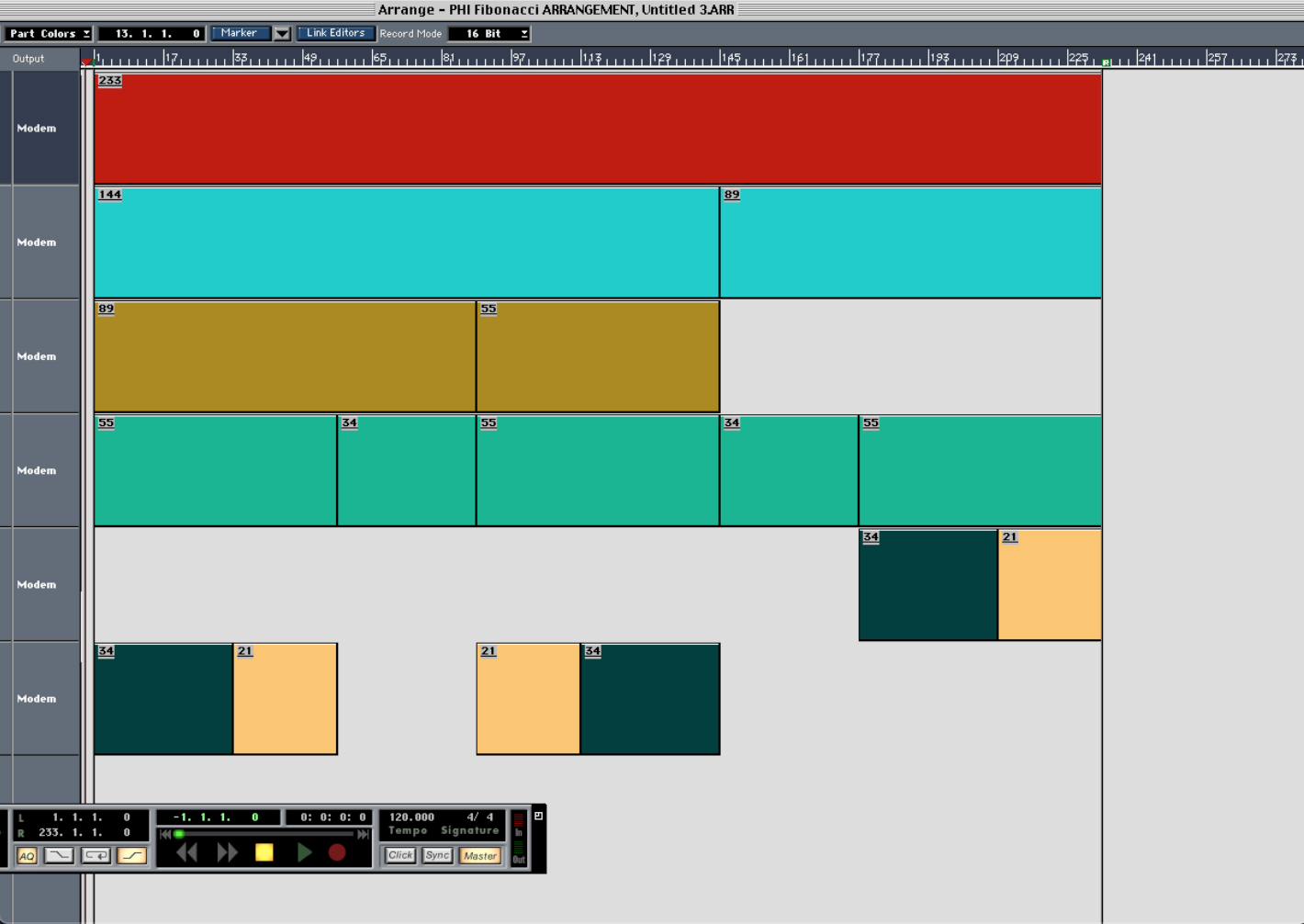

Here is a 232 bar song arrangement (See screenshot below.) By determining where the PHI points lie, you can use these moments to illustrate climactic or memorable parts in a song. You do this by multiplying a given amount by .618, and this will give you the next point. The first line is the whole, or 1/1.

The second line demonstrates the primary point of interest, at 144 bars. I multiplied 232 by .618 and rounded to the nearest logical measure. This marks where the beat comes back in after a long breakdown in many songs, although you don’t have to do the most obvious event there.

Next line, you have the PHI point of the main PHI point so something musical can happen here at 89 bars which will point to the main event. By repeating this process of determining Phi points and their PHI points, you come up with more PHI points, such as 55, 34 and 21 bars. These are building blocks—places where events can happen that accentuate a groove, perhaps where cymbal crashes occur. All these blocks have a forward and inverted position in the timeline, and there is a vortex that exists between them. So, for example, from 89 measures to 110, that’s where something very attention-grabbing could happen. It all comes down to observing one main ratio: .618.

This is the same ratio found in all aspects of life, just like a nautilus. So, by observing these ratios, you are working with nature and people can often feel it, though they may not be able to turn around and explain why everything happens at “just the right time.” You can also break these rules and that will give you something that goes against nature—which is another type of tension in itself. You can ignore it completely too, but by using established forms like this, you can create tensions, releases, or romanticism etc…with consistent intentions.

Basically, the blocks are laid out in this arrangement, and if you have events happening at these points in your song, it will be perceived as being “logical” by the listener. You can continue to find the PHI points of the PHI points, right down to the smallest rhythmic increment if you choose, and by doing this you are creating a conceptual model of some of the most dominant patterns that exist in life and creation. Or, by going against this form, you can really freak people out! Your call.

What percentage of tracks do you release?

It may surprise you to read this, but the answer is almost all of them. I’m not a producer who is sitting on a giant surplus of material. If I see a project through to the end, I release it. I mean, it’s a bit of a fluke that I had the track available for XLR8R+. I had been sitting on the multis for it for so long because I just knew there would be a time and place for it, simply because I liked the song.

How do you know when a track is finished?

I don’t mean this sarcastically, but basically, when you press stop on the recorder. You know while it is recording that you have captured a good take because you feel it.

Looking back at your biggest records, “Man or Mistress,” “Woman is an Angel,” were these different to the rest of your catalog?

You know you are on to something special when you are making the tunes but nobody can guarantee a hit record. I don’t see them being different to other songs though, they are all part of my catalog. It would be boring if I only made hits.

The benefit of being a bedroom producer and keeping in that mindset is that you can easily just make something you enjoy, then think about the other stuff later. I had an interesting experience lately because I am working on an LP right now. And I was driven to make something as advanced as I could, trying to push my own limits and musical technique, etc. But alongside this I have been making some other tunes, a bit more simple, just having fun and blowing off steam with them. And it dawned on me only this week that the tunes I have been noodling around with for fun are the ones that will make up the LP! I was blindsided with this notion. That’s a great benefit to being an independent label owner and artist, because I can just do a total 180 if I want to.

What determines whether a track will be released?

Honestly, it’s a tough question to answer definitively because there is no right way to do things, and there isn’t just one direction either. I make music all the time—I am a music addict. I make music for peace of mind, I do it for joy. I suppose I could say the songs that are giving the most to me when working on them are the ones I release. It’s a gut feeling, if that makes sense.

Do you finish all the tracks you’re working on, or how do you know when to ditch a sketch?

Yes, for the most part. Ninety-nine percent of the time writing a tune I will see it through to the end.

Do you ever produce and keep specific tracks for your DJ sets?

I do. I play exclusively my own music and edits in DJ sets.

So do you have different processes: one for DJ-friendly tracks and the other for tracks that you wish to release?

Yes, exactly. Although, I use different classification. I might think: This is gonna sound really cool! or, I wonder what would happen if I combined this and that, or even, how can I make people feel this certain emotion while on the dance floor?

At what point does it become clear that you’re producing for a release or a DJ tool? And how does this influence your processes?

Just legal limitations, I observe copyright laws with Novel Sound releases but with edits or anything in-between, I play those without publishing limitations. It’s not illegal or even disrespectful to play things in your DJ sets which could not be officially released. For example, I made a track which samples George Kraanz “Din Dah-Dah.” I made this tune knowing I couldn’t release it but I always liked that record because I heard it when I was about 11 years old and it had a big affect on me. I could never get the sample cleared in order to release it, but that doesn’t matter. I do play it all the time and people love it. And I like having all those tunes that are unique to my sets, because it means I am offering something unique as a DJ.

Is music making an immersive process?

Yes. I do like to live inside a song as it unfolds. Some come easy, some take all your life force away. Neither are really better than the other, however they are entirely different beasts.