Interview: Eddie Fowlkes

As Detroit's Movement festival approaches, one of techno's overlooked founders sets the record straight.

Interview: Eddie Fowlkes

As Detroit's Movement festival approaches, one of techno's overlooked founders sets the record straight.

“Oh, you really trying to kick up some dirt,” Detroit’s Eddie Fowlkes says with a laugh. We’ve been talking for 20 minutes, and I’ve just inquired if it caused a rift between himself, Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson when the U.K. press decided to run with the “Belleville Three” branding. He’s right to point out that it’s the first mention of Belleville since we sat down. “It didn’t cause a rift for me because I knew where I stand. I mean, everybody knows,” he answers. How, then, did Fowlkes, who identifies as the domino that set Detroit techno into motion, get edged out of the equation—and essentially become a footnote in the very book he helped to write?

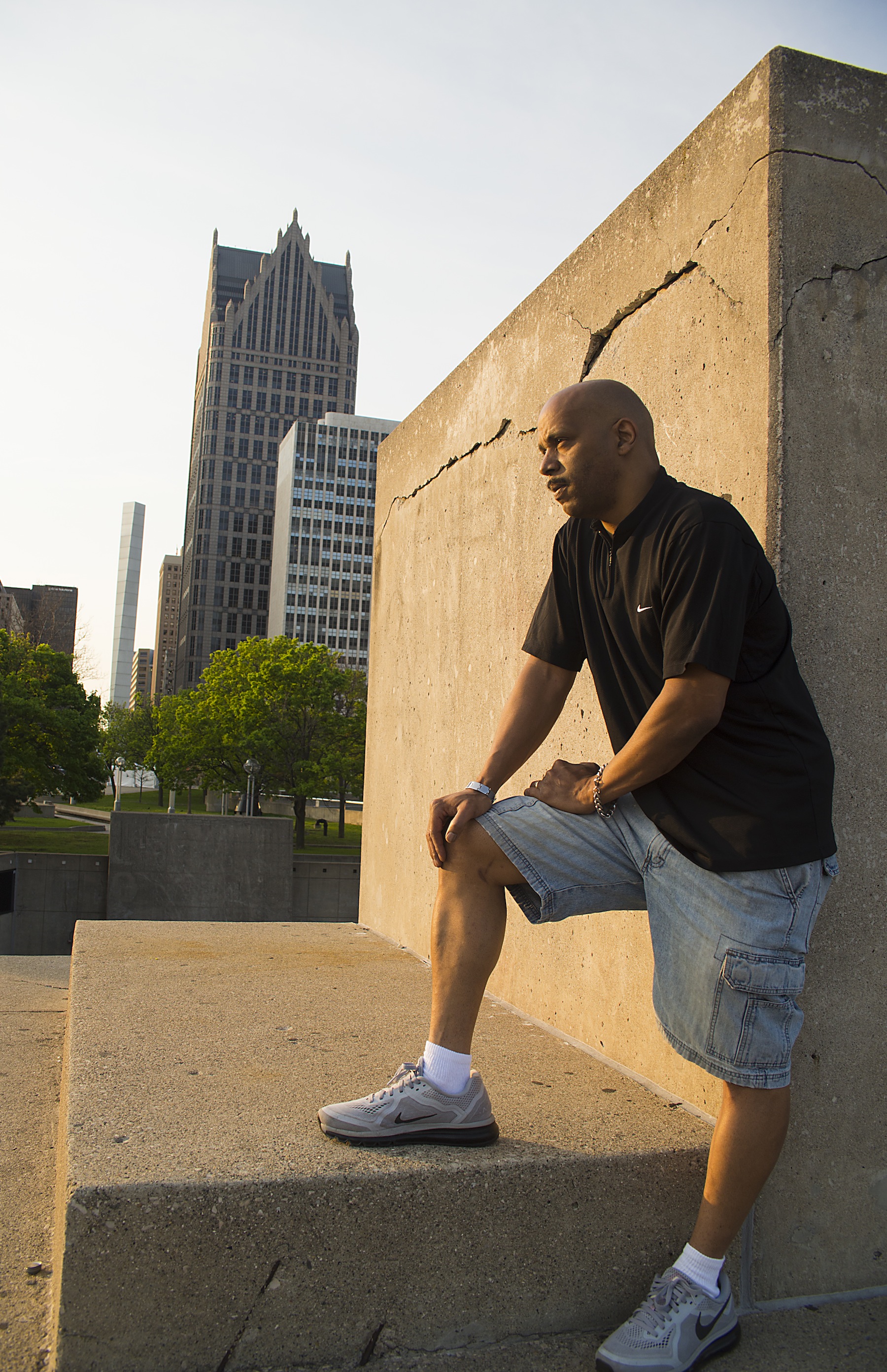

“I didn’t get along with Derrick May’s manager [at the time], Neil Rushton,” he explains. “Neil Rushton was an asshole, and Juan said he didn’t trust him. Somehow it came [back to him] that it was me said that, but it wasn’t.” Saunderson had just scored a huge hit with “Big Fun” and “you can’t be bigger than Juan in Detroit at this time.” So, with an ax to grind and the media at his fingertips, Rushton brought The Belleville Three into being. “Everything happened here,” Eddie declares, gazing at downtown Detroit from where we’re perched in Hart Plaza. “So that’s where the European press has got it wrong.”

Perusing the indexes of some of dance music’s most storied accounts—Techno Rebels and Last Night a DJ Saved My Life, specifically—Atkins, May and Saunderson get at least three-fold as many mentions as Fowlkes. Even recent features on Eddie continue to support, in their own way, the arbitrary rhetoric of the Belleville Three; the title of 2012’s “Eddie Fowlkes: The Belleville Fourth” appears to miss the very point the article is trying to make. Roommates with Derrick May for a while in Detroit, and having met Kevin Saunderson—the last to join the crew—in college, Belleville played no part in the techno tale until Rushton said it did. “All I know is Detroit,” Fowlkes sighs.

It seems that’s not the only time the press has misconstrued or reconstructed Eddie’s image. We ask about the context of a quote frequently cited and always attributed to him. According to the quote, he referred to ’90s European rave culture as “cultural rape.” “Are you sure that was me?” he asks. “I think that’s a Derrick May comment. I couldn’t care. Naw, that’s not even me. I embrace the Europeans playing our music, supporting what we do. That don’t sound like me. They got that real twisted,” he insists.

Nor is Fowlkes a fan of the labels “First Wave” and “Second Wave” so often used to describe the two initial thrusts of Detroit techno trailblazers. “I don’t really care for that because it’s like, that’s a part of separation. I think that, in the beginning, we all did it for the love. And when you come with this ‘Second Wave,’ which the European magazines started that, it started to kind of divide who’s better than whom. You start chopping us up, we can’t come together to create this thing that we started. I thought that was kinda unfair. But they didn’t know. They still don’t know.”

“I’ve seen people sell their souls to the fullest extent…they don’t understand that music is a vibration in your body. It’ll make you dance. It’s a spiritual thing.”

He isn’t bitter or begrudging about any of it, though: “God used a certain person to have a snowball effect. And to answer your question again, there’s no rift because I know this was meant to happen,” he reiterates. His story only beginning to surface in the last few years, Fowlkes finally seems to be getting his deserved and long overdue recognition. In 2012 he was honored by the Detroit Historical Museum in their exhibit “Techno: Detroit’s Gift to the World.” Along with Atkins, May, Saunderson, Jeff Mills and Carl Craig—the first three and Fowlkes designated as “Techno Pioneers,” Craig and Mills as “Techno Artists,” respectively—his hand prints are permanently on display in Legends Plaza alongside fellow Detroit luminaries from Gordie Howe to Alice Cooper. At the very mention of it, he throws his hand in the air, instigating an impassioned high-five. “That’s the best thing we ever could have because that’s going to be there forever,” he gushes. “This is something that will keep our legacy [alive].” A few days after our interview, the four pioneers are honored again, this time at the annual Ford Freedom Awards, for their creation of techno.

Fowlkes reflects, “I really think that I’m truly blessed that music chose me. People don’t realize music chooses you, you don’t choose music…[I’m] just glad to see that this whole thing took on the world.” He does identify a darker side to the industry, though. “The sad part is people use it in the wrong way. To down people, just to sell they soul. I mean, I’ve seen people sell their souls to the fullest extent…they don’t understand that music is a vibration in your body. It’ll make you dance. It’s a spiritual thing. And if you don’t have that spirit, you’re dead. And there’s a lot of dead souls behind these so-called, uh, turntables.”

Since his side of the story is still somewhat in its infancy, the CliffsNotes version goes something like this, according to Eddie: He had an intense epiphany at a Deep Space party—the collective formed with Atkins, May, Art Payne and Keith Martin—in the midst of a Cybotron performance. Interested solely in DJing up until that point, he decided in that moment to make his first record. Borrowing equipment from Juan, he trained his ear and taught himself to play the keyboard over a couple of months. The result was “Goodbye Kiss.” Released on Atkins’ Metroplex imprint, it’s distinguished in Dan Sicko’s Techno Rebels as being the label’s “first proper ‘techno’ success.” In the interim, word had gotten back to May and Saunderson that Fowlkes was in the studio making music, inspiring them to do the same.

Fowlkes, who has dropped the “Flashin’” from his name, was the party boy of the posse, admittedly wilder and less focused than Atkins. So the others figured, “’If Eddie can make a record, I can make a record.’” Hence, he was the catalyst for the cosmic new sounds coming out of Detroit.

Despite his impact finally making its way into this seminal saga, Eddie doesn’t seek credit or crave the spotlight. Quite the opposite: He’s quick to recognize the group dynamic responsible for the late-’80s evolution of electronic music. Exuding humility, gratitude and the youthful energy of his flashy former handle, the only thing Fowlkes says he would change, if he could go back in time, is to approach DJing as more of a business from the beginning. Other than that, he’s genuinely content with the way his career has gone. And over Memorial Day weekend, he’s been invited by Atkins to play the Metroplex 30-Year Anniversary Showcase at Detroit’s Movement. How does he feel looking back on three decades of Detroit techno? “You know, I never put a time [or] age to my hook-up because that makes me feel old. I’m not old. I’m young as hell. For real. I’m still young, still having fun, and music is therapy for me, and it should be for everybody.”

Eddie Fowlkes plays the Movement festival’s Metroplex 30-Year Anniversary Showcase Sunday, May 24 at 9pm.