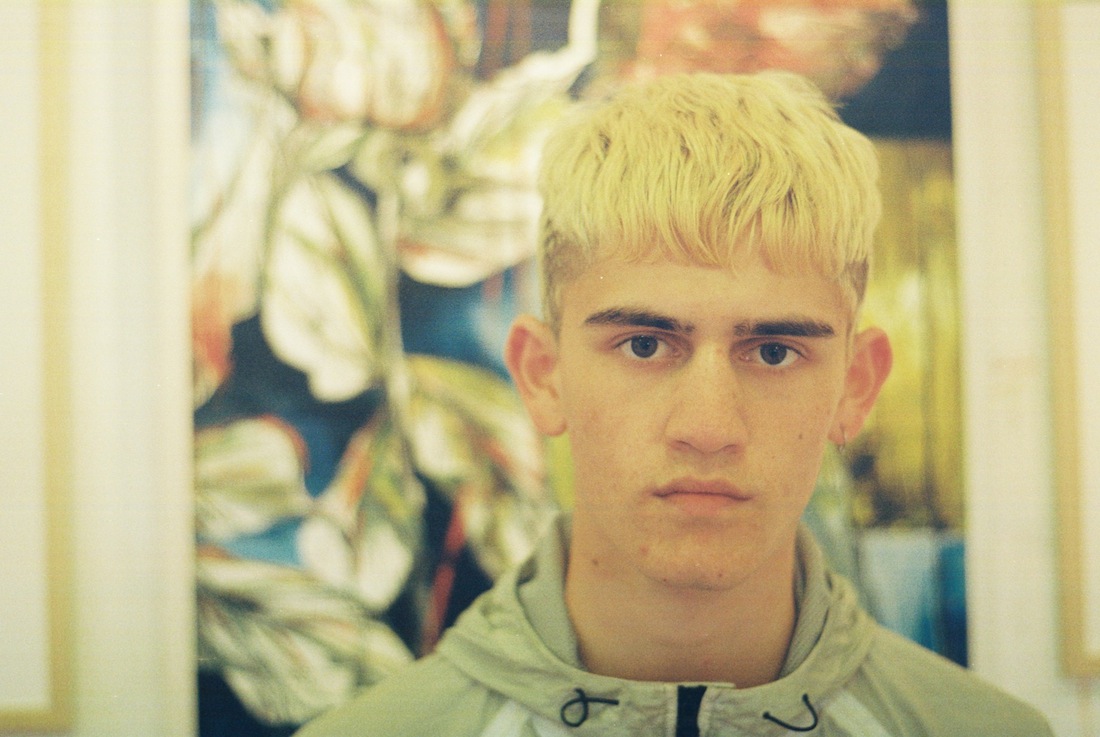

Interview: Happa

The Leeds-based producer may be young, but he's a mature and accomplished artist.

Interview: Happa

The Leeds-based producer may be young, but he's a mature and accomplished artist.

It’s refreshing to meet someone who has been making huge waves in the European electronic scene for the last three years, but remains down to earth and honest—perhaps even humble. Needless to say, then, when 18-year-old British producer and DJ Happa (a.k.a. Samir Alikhanizadeh) fesses up to carrying his records to gigs in a canvas bag, rather than a ready-made record case—a situation he describes as “pretty ghetto”—you immediately warm to him. Add his statement about “only really making music that sounds like it was dig up from the ground,” and we’re sold on just how straight talking the guy can be.

Shooting to fame via attention from BBC Radio tastemaker Mary Ann Hobbs, then being asked by Four Tet to remix a single at age 15, it didn’t take long for Happa to establish a loyal following. Perhaps it’s the way his hometown—the once-industrial city of Leeds—can be heard in the raw and uncompromising aural aesthetics he paints. Maybe it’s his approach to playing records—attacking, demanding, full throttle yet audibly influenced by IDM, concerned with experimental tones and obsessed by the desire to avoid dull repetition. Either way, he’s a worthy addition to a proud local heritage of club culture that spans decades, and includes the Orbit (arguably the finest techno party to ever grace the north of England), Back to Basics, Hessle Audio and 20/20 Vision, to name but a handful.

With that in mind, XLR8R was keen to meet him—which we did, in the rooftop bar of one of Leeds’ most respected venues, Belgrave Music Hall. With sun breaking through clouds, and pints of beer in hand, we began the conversation by asking how a high school kid gets commissioned by one of the biggest names in global electronica.

“The first thing I put out was through the London label and club night, Church. I think my EP was the first they had put out, apart from a white label, Happa recalls. “There was support from Mary Anne Hobbs, and then Four Tet came along. I’d made this track, “Freak,” which I ended up giving away as a free download for Christmas I think. Anyway, Four Tet somehow found this online and sent a tweet out. Before that, it had maybe 1,000 plays. Afterwards that number jumped to about 17,000. Then I got an email from Mary Anne Hobbs saying ‘Four Tet wants your email—am I OK to give it to him?’ Of course, I jumped at the chance. He was in touch pretty quickly asking about doing a remix, which is still the biggest thing I’ve done to date in terms of plays and exposure.”

Flying too close to the sun, too soon, is a mistake many up and comers make. Happa’s open approach to this line of questioning only adds to his charm. “Yeah, at first I was a bit like, where from here?” he admits. “But thankfully, I’ve got some great support in management. They have been crucial in terms of holding me back, in a good way. They give me free reign over some stuff; for example, I did an EP for Boomkat Editions. I had been pigeonholed into this bassy-house kind of thing. I’ve never really been like that, or never really been about one thing. Originally, when I was first messing about, I made really, really terrible dubstep. That Boomkat EP was a chance to show people what I’m really about. So it was great—but if I had been on my own, I probably would have taken every offer from every label.”

“At first I kind of played up to my age a bit, as I noticed people were picking up on it. Maybe six months after the Four Tet remix, it was getting a little annoying. After a year I’d definitely had enough.”

At the time, one of the major talking points regarding Happa was his age. Still one year away from college, and too young to legally attend the events his music was made for, there was always going to be a concern that the that hype stems more from circumstance than anything else. “Yeah, that was a bit of a worry,” Happa admits. “At first I kind of played up to my age a bit, as I noticed people were picking up on it. Maybe six months after the Four Tet remix, it was getting a little annoying. After a year I’d definitely had enough. I’d never be precious and ask people not to write about it, but I don’t think it’s important anymore.”

The conversation veers towards the origins of Happa’s love for electronic sounds, which in some instances are as abrasive as they are beautiful. “I was about ten or eleven years old,” he recalls, “the age when you’re about to go into high school. My older sister and brother were both into electronic stuff. It wasn’t their main thing, but they liked dubstep and things like that: DMZ, Tempa.… I remember being outside my brother’s room and he was playing Rusko’s “Cockney Thug.” It’s a typical Rusko tune, samples from the movie Snatch or whatever—Cockney gangsters swearing and shouting, with trumpets. He cranked the volume right up and I just went in there and said ‘What the hell is this? This is crazy.’ Over the next few years I fell in love with it all.”

He continues: “Things progressed from there. I think you can still hear that dubstep influence in me. Especially as I went from straight-up stuff onto Swamp 81 and Hessle Audio; mixing house, techno and dubstep. Then I discovered Tim Hecker, by accident really. I bought James Blake‘s first album, a Caribou CD, one by Nicolas Jaar and then Ravedeath, 1972 by Tim Hecker. I’d only heard of the first two, the others were recommended by Amazon when I ordered those. I think. Anyway, I put Ravedeath on in the car with my mum and was just like, what the fuck is this? Really weird. I fell in love with the James Blake and Caribou albums instantly, but this one I left for about a year. Then we were in the car again, I put it on—and although my music tastes hadn’t really changed in that time, I was blown away after hearing it again. Then I got into people like Ben Frost and loads of brutal industrial stuff—which is where I’m at now.”

Despite its heritage, Leeds currently doesn’t shout anywhere near as loud as it once did, insofar as events and clubs go…or, at least, it doesn’t from the outside looking in. We ask Happa to divulge, and whether he’d ever jump ship from his native domain. “Leeds really likes a good party, and can get quite messy,” he says. “But I don’t see much of a scene here for me, in terms of what I want to see and what I want to go out to. Every now and then there’s something good going on clubwise. Selective Hearing do some great things here, but there’s not really a thriving techno scene overall in terms of live music. It’s better for bands, my friends tell me, although to be honest I’m a bit of a hermit crab. In terms of moving, even just one hour down the motorway to Manchester, there seems to be so much more happening. So maybe.”

Tentatively, and through a near-cringe, we mention the ongoing diaspora of British talent to Berlin. Reassuringly, we’re met with another refreshing response. And laughter. “From my experience it’s an amazing city, Happa says, “but I just love England so much. It’s an incredible country. I recently went on holiday to Crete after a festival in Athens. When I got back I was walking from a friend’s house home and had this moment: Staring at the uneven pavements, the dark streets, I couldn’t believe how much I’d missed it. The gritty grimness is what makes the place.”

That same grit and griminess that can be heard on PT1, the latest EP from Happa. The track “Chewy Teeth” sounds like roadwork somehow trapped in a trance-tipped, subtly uplifting techno assault. An offering he’s deservingly proud of, it’s the first notable cut to come from his label, PT/5. He’s quick to point out, though, that this isn’t the first cut from PT/5. “”We put out an EP by these two guys from Leicester, Witch,” he explains. “There were two tracks by them—both wall to wall solid techno, but also quite crazy. On top of that there were two remixes, by Truss and then Shifted. I loved the EP, but it didn’t do very well sales wise. There were delays and issues. So Part 1 is like the proper start of things.”

“I’ve always wanted to run a label,” the producer admits. “Me and a guy called Al, who has kind of drifted away from things a bit now, started PT/5. We used to set up labels to give away free downloads of tunes our friends made, but after every track we’d pretty much be bored of that one and start a new one—new name, new logo. The whole idea of how iconic a label can be, and how crucial it can be to a genre, it amazes me. Also the idea of taking someone’s music and sharing it with the world. Sharing the joy, it’s what music is all about. Not that I want to sound like a total hippy.”

“It’s important to consider what you play properly. If it’s all for you, it’s self-indulgent; if it’s all for the crowd, it’s boring.”

This notion of disseminating ideas, both personal and those in the work of others, is a part of Happa’s DJing, and his attitude towards the role puts many more seasoned and arrogant jocks to shame. “I think going to see someone play out isn’t just about hearing what you think you want beforehand. I want to hear something shocking, or surprising, or funny. I don’t think you should be limited to just feeling one thing at a club night. I’d prefer to take a few risks and see what happens. Some people you can see get it. Others just look confused. And then there are a few that seem to get angry. In a way I wish some people were a bit more open-minded in terms of what they want to hear. Much as I love the monotony of techno, it’s also good to have some difference. It’s important to consider what you play properly. If it’s all for you, it’s self-indulgent; if it’s all for the crowd, it’s boring. It’s all about keeping things interesting, and thinking about how that works.”

Like we said—refreshing.

Happa’s PT1 is available now on PT/5 Records.