Interview: Kode9

Emptiness and loss serve as the catalysts for the Hyperdub founder's new album.

Interview: Kode9

Emptiness and loss serve as the catalysts for the Hyperdub founder's new album.

On New Years Eve of 2014, Kode9 scrapped almost all the music he had been working on for the past year. “Everything I was making was really synthy and didn’t capture how I was feeling,” he explained. “I wanted it to be colder, more isolated, emptier.”

2014 was a bipolar year for the man born Steve Goodman. Hyperdub, his label and brainchild, celebrated its ten-year anniversary with an extensive four-volume compilation that highlighted a discography at the forefront of shifting sounds in electronic music. However, 2014 was also a year of significant loss, with the sudden passing of DJ Rashad in April, and Spaceape succumbing to a long battle with cancer in October. Hyperdub’s first releases were Spaceape-Kode9 collaborations, and he had been a mainstay on the label ever since. DJ Rashad, meanwhile. was perhaps the label’s most promising artist; his Double Cup LP was massively influential, and one of the most memorable records in recent electronic music. The pain of loss was felt for the label—and even more so for for Goodman himself.

Born in Glasglow and raised on the original wave of jungle that swept over the U.K., Goodman has had an incredible career as a musician, label head, and academic. Although he’s no longer teaching at a university level, he holds a doctorate in philosophy, and published a book through MIT Press, Sonic Warfare, on the historic use of sound as a weapon. He was at the forefront of the dubstep movement, and comes from a class of originators out of Plastic People’s seminal FWD>> nights. As a label head, his promotion of music from the Teklife crew helped to export Chicago’s footwork sound around the globe. With releases from Burial, Zomby, DJ Rashad, Darkstar and Hype Williams, in addition to the two LPs he released with Spaceape, Goodman has lead Hyperdub to be the gold standard for electronic-music record labels.

But in January this year, “I had to draw to a line on everything—it was too fucking intense,” he admits. “First with the disappearance of Rashad, my biggest recent influence, and then with the death of Spaceape, one of my closest friends and longest-term collaborator. I had to go into complete sensory deprivation.” After scrapping almost all the warmer synth material he had made in the last year, he began working on a new album, trying to channel everything that had happened in 2014 into music that reflected how he was actually feeling—something icier. “I didn’t let anyone hear it,” he says. “I didn’t share it with anyone. I didn’t get any feedback. I didn’t even test-drive it on audiences. I don’t really remember talking to anyone in the month of January.” That LP, Nothing, (coming out November 13) serves as his first true solo album, the first he’s made without Spaceape.

“I have to start with some sort of concept, and the one I came up with on New Year’s Eve was nothing—nothing as a placeholder, an anti-concept. But when I started to research the concept, I started to realize what ‘nothing’ really was.”

“I felt that the most honest way I could have a concept that related to the music would be an empty concept,” Goodman explains. “There was so much going on in my head when I started the record, that I couldn’t really put it into words.” For him, Nothing is a catharsis, the result of accepting the effect subtraction has on our lives. Each track title is a different iteration of how the idea of void or space plays out in everyday life, ranging from Taoist philosophy, to Marxist economic theory, to quantum physics. “I have to start with some sort of concept, and the one I came up with on New Year’s Eve was nothing—nothing as a placeholder, an anti-concept. But when I started to research the concept, I started to realize what ‘nothing’ really was.”

The first six months of 2015 were the slowest in Hyperdub’s history, as Goodman had to put his A&R duties for the label on hold while making the album. He was reluctant to listen to anybody else’s music during the recording of Nothing, and the use of outside samples was limited. Whereas his last LP, Black Sun, took three or four years to come together, Nothing was composed almost entirely in the month of January. The album became a synthesis of all Goodman’s previous work, with little regard for any current trends in music. “It was sort of inevitable with the anti-concept of nothing that the album would wind up in the vanishing point between grime, dubstep, footwork, a film soundtrack,” he says.

Thankfully, Goodman eventually came out of his isolation, and Hyperdub’s release schedule has picked up again. He spoke enthusiastically of one of their most recent releases, the Break it Down EP from Teklife’s DJ Taye. There’s a sample on the EP’s third track, “XTCC”: “There’s a void where there should be ecstasy.” “I don’t know if it’s the death of Rashad that’s put us all in that head space,” Goodman says of that vocal snippet, “but something that was important to all of us has been subtracted, and we’re dealing with that void.”

DJ Rashad’s presence on Nothing is tangible through the footwork rhythms on many of the album’s cuts— Spaceape’s place on the record, however, is less obvious. The track “Void” was the only one composed before January of this year, and it was intended to include Spaceape’s vocals. “Third Ear Transmission” gives a taste of the MC’s snarl, but it’s not till the album’s conclusion that Spaceape’s loss is really felt. Nothing ends with nine minutes of almost total silence, and that final track is the only one on the album that lacks a firm philosophical grounding. Goodman said of the closing silence, “I just wanted to carve out room for Spaceape to come back in, his presence felt again.”

Even though the process of composing Nothing came out of deep loss, the album doesn’t resonate as a particularly emotional or overwrought. With Black Sun, the diagnosis of Spaceape’s cancer lingered over the production process, and part of the challenge was channeling Spaceape’s battle with cancer into the concept of a post-nuclear science fiction story. The process of composing Nothing was similar. As Goodman puts it, “It’s come out of something quite personal, but its become something that really has nothing to do with my emotions at all. I’m not interested in music being an expression of my emotions, or a biography of me because I don’t think it’s important or interesting.”

Much of the producer’s work has dealt with the concept of the future, and Nothing is no exception. On the surface, this future is bleak. The first few tracks show a cold indifference to the world, as the album survey’s the landscape of an automated future—but the indifference slowly thaws into acceptance. You can feel Goodman beginning to emerge from his isolation with the wavy fuzz of the album’s later tracks, like “Mirage.” Whereas much of his older material communicated a sense of dread common in early U.K. dubstep records, Nothing has no tangible sense of anxiety about the future. The process of robots automating our lives is something he’s actually quite excited about, saying, “I’m very positive about the possibility of machines making humans redundant.”

The physical manifestation of this idea of nothingness seems to be the impetus to Goodman’s Nøtel concept. Sitting in the courtyard of his hotel, he pointed to our surroundings: the pseudo-disposable modern furniture, repeating identical rooms, the coldness found in hotel hospitality. “It’s in staying in places like this where the Notel concept comes from,” he says.

Next year, Goodman will take the Nøtel concept on tour with Lawrence Lek, a visual artist whose work plays upon the themes found in neoliberal architecture, and the wealth that surrounds it. The concept is still in a prototype stage, but the vision is that Lek will control a virtual simulation of a walk-through environment as Goodman plays live. The premise is a wildlife documentary approach to a fully-automated luxury hotel where all the humans have been evacuated. “We don’t know why there are no humans there, could be an apocalyptic event, could have been a virus,” he says. “Who knows? The reason why there are no humans isn’t the relevant aspect.”

Compared to previous Goodman releases, Nothing has a relatively small number of outside samples, and the majority of the record was created with from original patches. But one of the few familiar sounds is taken from the film Seven Samurai. The sample first appeared as part of Goodman’s Spaceape collaboration, specifically the track “9 Samurai,” and it’s reprised on Nothing‘s penultimate track, “9 Drones.” The new song links Goodman’s contemporary footwork-influenced work with his early material, and highlights one of his preoccupations: full automation. The idea of drones replacing samurai brings up the question of what happens to us, or what will we do, when our presence in no longer required on this earth.

Goodman speaks frequently about a world where humans are no longer required, or no longer present—and, as noted earlier, he doesn’t dread the idea. Instead, he contemplates a post-human world with curiosity. If we all left tomorrow, what would remain? What would be left in the presence of our void? One of his favorite films is the Philip Glass–scored documentary Koyaanisqatsi, a film that shows life on earth’s accelerating trajectory. In Koyaaniqatsi,, the movement of our man-made systems becomes so fast that they collapse in on themselves, with humanity’s future remaining open-ended. Goodman describes the Nøtel as what exists on the other side of that collapse. “Maybe the Nøtel is where Spaceape and Rashad are now,” he says. “Their presence being felt as holograms.”

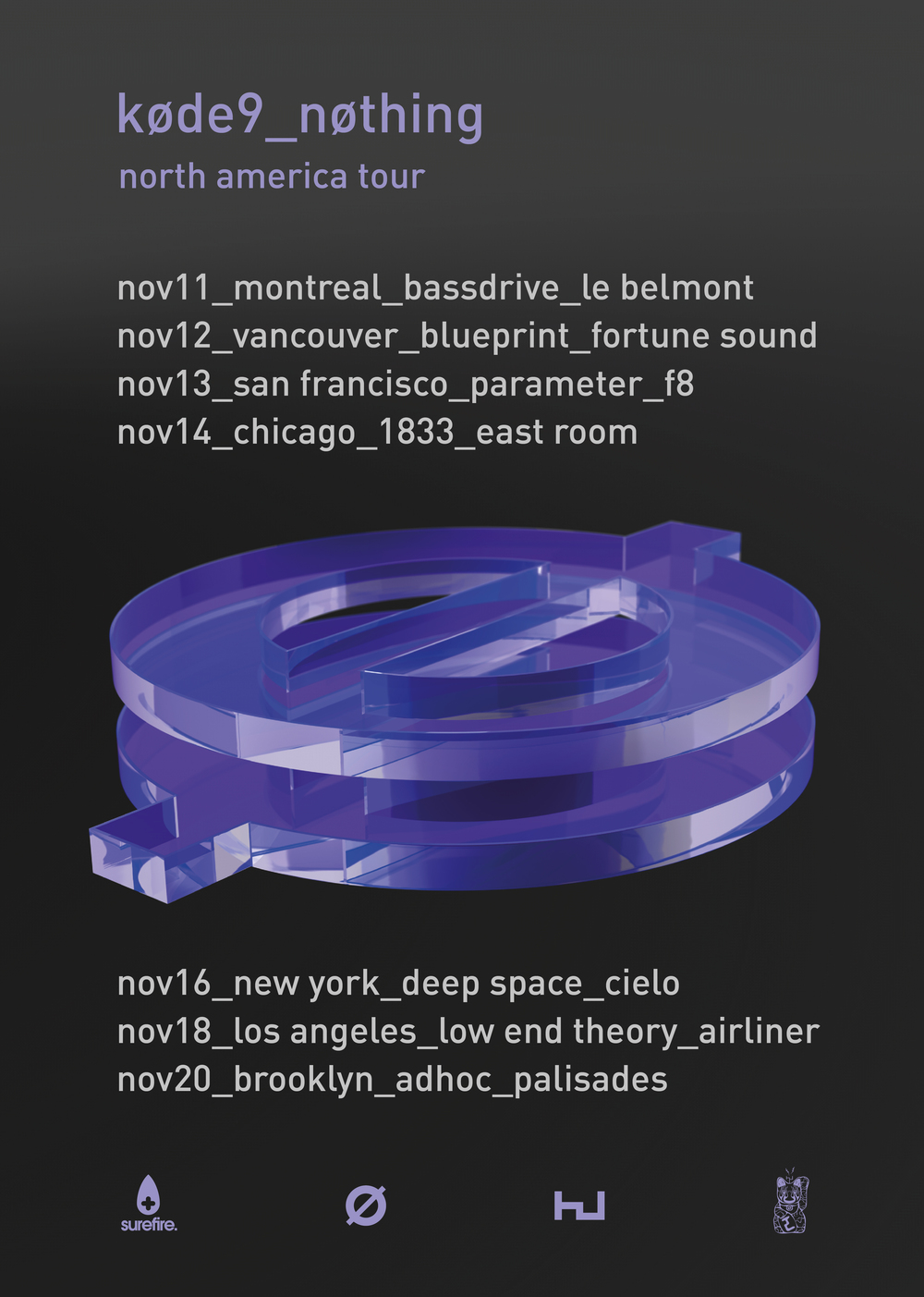

Nothingis released on Hyperdub November 13; see below for Kode9’s upcoming North American DJ dates.

Photos: Philip Skoczkowski