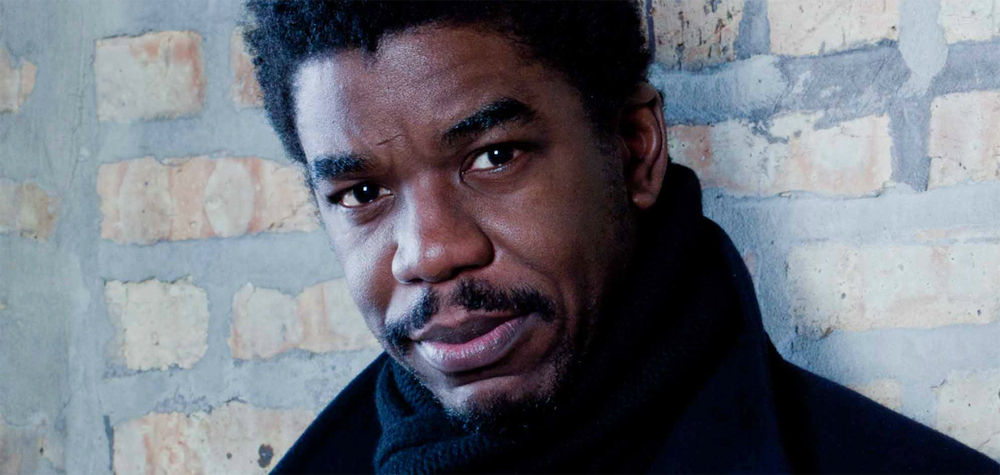

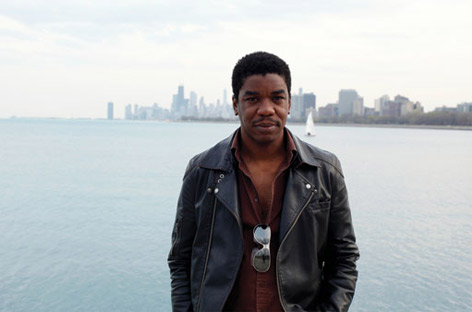

Interview: Virgo Four’s Merwyn Sanders

Heading into a live gig at Warm Up, the Chicago house veteran tells his side of the story.

Interview: Virgo Four’s Merwyn Sanders

Heading into a live gig at Warm Up, the Chicago house veteran tells his side of the story.

If Merwyn Sanders knows that he’s one of Chicago house music’s most formative producers, he certainly doesn’t act like it. His work with Virgo Four spawned some of the genre’s most formative tracks, and yet still managed to carve out a sound that’s completely different from anybody else.

His career has been a bit of an odd one. The group we now know as Virgo Four—occasionally known simply as Virgo, not to be confused with the Marshall Jefferson project of the same name—was originally composed of two members, Merwyn Sanders and Eric Lewis. The two worked together in the late ’80s, and stopped collaborating altogether around 1992. But in 2010, Rush Hour rereleased their 1989 album Virgo, and in 2011, put out a large collection of unreleased material, Resurrection. Virgo Four started to tour again, and it seemed as if Sanders and Lewis had come back together.

But in a 2013 Resident Advisor article, it was revealed that Merwyn Sanders and Eric Lewis had split two years earlier, and that Lewis had been touring as Virgo Four against Sanders’ wishes. Lewis used his cousin as a replacement for Merwyn on vocals, guitar, and synths, and continued to use all the promotional materials that featured Merwyn’s name and face. It was only after the RA article was published that Eric updated the Virgo Four site to say: “The clock’s rolled on and Merwyn’s pursued a different musical path, but Eric and new recruit Terry Ivy are continuing the legacy without missing a step.”

Here, Merwyn Sanders finally gets to tell his side of the story, as he gears up for a live set under the Virgo Four moniker at New York’s weekly Warm Up party at MoMA PS1.

Could you tell me a little bit about what goes into your live sets?

Everything is hardware. Instead of any backing tracks, I’m doing everything live through a guitar, groove boxes, synth modules, and drums machines. I tried a laptop, and I know a lot of people use Ableton Live now, but I didn’t feel that a laptop would encompass “live.” For this show, it’s actually going to be three people: My wife handling the drum machine and synth module; Aaron Rivera, who is great on bass and also plays synth; and then myself. I’ll be able to do all the other keyboard parts on my guitar, as well as the vocals.

How similar is that to the way you make music in the studio?

Back in the day, we were high school kids and we didn’t have a ton of cash so we got what we could. I started off with a Roland Juno 1, and then later on, Eric wound up getting the Juno 2 as well as the Roland 505 drum machine. We actually wanted more expensive gear—which is interesting, because now we’re associated with the sound of those old keyboards, and everybody is trying to get back to that analog sound. We didn’t use a sequencer very often, we were always sequencing through the drum machine. We would play our parts live and then just record it. Most of the tracks I did alone or by myself, and then maybe Eric would add another part later.

Could you talk about your vocals? A lot of live Chicago house vocals seem to draw from soul and gospel, but your vocals feel a lot more in line with U.K. new wave, particularly on songs like ‘Never Want to Lose You.’

“Never Wanna Lose” was my answer to Chicago Syndicate’s “Move Your Body.” My vocals ended up the way they did because I couldn’t sing. I had no formal practice or training, I was so into just the music aspect. I wanted to sing because I felt that it was a necessary part of music and performing. And the confidence wasn’t there too—singing is so much about confidence—and if you don’t feel good about how you sound, or how you’re singing, it’s not going to come out well. So what you’re hearing on that stuff is a young kid just not being the greatest singer—it’s that simple. But that’s where the style came from, from new wave music. I loved the way David Bowie sang, those kind of cool male vocals he would do.

Why do you think new wave resonated with so many people in Chicago at this time?

We just listened to so much music. What was happening with DJs at that time was you just used anything you could get your hands on, and play it like a house record. I think at the time the community listened to everything anyway—so when new music, like house music, was starting, it was going to be incorporating everything we grew up on. I remember one time I did a live remix of the Talking Heads track, “Once in a Lifetime.” I was watching that movie Down and Out in Beverly Hills and I’ll never forget. That track came on, and it hit me: That’s a house track!

Ron Hardy was somebody who spun a lot of new wave—could you talk about his influence on you?

Ron had a huge effect because he would do remixes in a way where you would just go wow! People were always saying, “Did you hear what he did with such and such?” And he was my favorite DJ for a while. One mix that really stands out was when he remixed Klein + MBO with “Let No Man Put Asunder.” What he did with the vocals on that track really just opened my mind. He just made you think in a different way. For Frankie Knuckles, it was what he played, but for Ron Hardy, it was all about how he played it.I used to get tapes from friends, and then I met him personally before he passed away, to work on the track “It’s Hot.”

You were working with Ron Hardy when he died?

He was working with Larry Sherman over at Trax Records to give his input on records for what would work or what wouldn’t. We had heard he was playing our demo of “It’s Hot.” I was talking to Larry about putting it out, but then he arranged it so that Ron and I could meet up and talk about some things. Ron had some ideas, so we just met twice over at Trax Records. We would sit down, listen to the track, talk a little bit. I was just more interested in talking about other things, Music Box and all that. I wanted to talk about DJ stuff! Him and Frankie Knuckles were already local legends, so that’s what I wanted to talk about. And he was just a really cool laid back guy. He wasn’t walking around like “Oh, I’m Ron Hardy.” I thought that was really cool, really nice. But then right after, I heard he passed away, and that’s sort of why not much came after that.

“It’s Hot” didn’t wind up getting released until your Resurrection LP with Rush Hour in 2010, right?

Yeah.

How did you guys get set up with Rush Hour records?

Christiaan MacDonald was the label manager at Rush Hour at the time, and he reached out to me when he saw an article written by Jacob Arnold. He said he was interested in rereleasing the Virgo Four album, so I talked to Eric about it and he said, “Let’s do it, why not?” And that went over well, and he asked if we had any other music, and it was like “Yeah!” So we started telling him what we had, and he flew out to Chicago to sit down and go over everything. He just sat and listened, and picked and choose, and that’s how Resurrection came about.

One of the tracks that I think reintroduced you to a lot of people is “Fannie Likes 2 Dance,” which was on Joy Orbison’s Essential Mix from last year. Could you talk about that track a little bit?

That track is actually a great example of me not being Virgo Four. I did that in 1999 as me—my other nickname Merle. The first line of lyrics started because I was trying to connect with people who like to dance a lot, like someone who’s in counseling for dancing. So that first line, “My name is Fannie and I like to dance a lot” is written from the place of somebody sitting in a circle at an Alcoholics Anonymous type thing confessing to people that they like to dance, and the rest of the lyrics followed.

I knew it sounded kind of weird, and I even asked a friend, “What do you think about this?” and he was like, “Yeah put it out!” So I went on and did it, and then no response—nothing, not a word. I didn’t hear anything. So I had those records sitting around, and they started to get mixed in with my other records and I stopped caring about them. I probably resented them, they weren’t being taken care of, and I thought, “Why do I have 200 records sitting here?” I thought maybe I could resell the wax. I threw almost all of them out, but somehow that record lived on. And it just got repressed!

Vinyl records are something that’s essential to the DNA of Chicago House music—how do you feel your records being digitized?

I don’t like DJing with MP3s. I grew up DJing, and I still have my records, and still would prefer to DJ with vinyl. In terms of sharing my music, I’m not an analog purist. I think that’s technology changing growing in different ways. It just gives one more platform to share your music, and ultimately that’s what its about to me.

Is it possible that people might not talk about and remember Virgo Four the way they do unless these tracks had been digitized?

It’s true! And that’s how I try to imagine things.

Something that’s being talked about now is how some of the originators of house music are getting left behind—and there’s a larger issue, since Chicago House music was really important to the black and Latino gay communities.

It was a black and Latino gay community, but I think it was even larger than that. The community was really just about the music, and I think that’s part of what’s missing today. That left-behind thing is something that I talk about a lot with Rodney Bakerr of Rockin’ House Records. The audience doesn’t know that this history goes back 30 years, and people are forgetting about the place this all comes from. But I think there always will be somebody out there who tries to remember it, and tries to bring it back so it does live on.

“Ultimately, what I came to realize is that Virgo Four really is my music.”

There’s so much misinformation about Virgo Four—can you clear the air and give everybody a clear idea of how everything went down?

I think if you really look at everything and follow my steps here and there, you can figure out what’s going on just by the music. The first thing is that people should know is that Virgo Four wasn’t our name. Larry Sherman put that on the record without telling us, and once the record was pressed up and printed, we had to go along with it. What else could we do? We weren’t going to not release our first record because we wanted to protest a name change.

The reason he called us Virgo Four was to get the name recognition from the Virgo tracks that Vince Lawrence, Marshall Jefferson and Adonis collaborated on. They did three records as Virgo, so Larry pressed us as Virgo Four. It was decided later with Rush Hour to keep using Virgo Four, because that’s what it was originally released as. But after that, I decided I wanted to split. Most of the Virgo Four stuff was solely me anyways, so I wanted to break away from Eric and just do my own thing. Eric had other ideas that I didn’t want to do, and so after we released Resurrection with Rush Hour, I stopped wanting to perform as Virgo Four.

But ultimately, what I came to realize is that Virgo Four really is my music. People know it as Virgo Four so that’s kind of my legacy. I was never walking away from the music, I was trying to walk away from that name. But, over the past couple of years, I’ve come to realize that people associate my music with that name. That’s why I’ve come back around to doing the Virgo Four tracks.

It’s even weird for me to say “the Virgo Four tracks,” because it’s me. Sometimes people talk to me about Virgo Four in the third person, and it’s strange, because for me it’s like…you’re talking about me, Merwyn! I was just trying to be Merwyn, but then I came to realize that people are associating my music with Virgo Four, so I realized maybe I should just embrace it. A lot of people had been encouraging me, “Merwyn, that’s your music, and people know it as Virgo Four—don’t push it away, that’s you!”

Merwyn Sanders, along with Nicky Siano, Cut Copy, Galcher Lustwerk, DJ Richard, and Bobbito Garcia plays Saturday July 4th at MoMA PS1’s Warm Up series.